The Sweet Cheat Gone (The Fugitive) Proust, Marcel (Translator: C K Scott Moncrieff)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 2:18-Mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 32

Case 2:18-mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 32 1 MCGREGOR W. SCOTT United States Attorney 2 AUDREY B. HEMESATH HEIKO P. COPPOLA 3 Assistant United States Attorneys 501 I Street, Suite 10-100 4 Sacramento, CA 95814 Telephone: (916) 554-2700 5 CHRISTOPHER J. SMITH 6 Acting Associate Director 7 JOHN D. RIESENBERG Trial Attorney 8 Office of International Affairs Criminal Division 9 U.S. Department of Justice 1301 New York Avenue NW 10 Washington, D.C. 20530 11 Telephone: (202) 514-0000 12 Attorneys for Plaintiff 13 United States of America 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 15 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 16 17 IN THE MATTER OF 18 THE EXTRADITION OF OMAR AMEEN CASE NO. 2:18-MJ-0152 EFB 19 20 21 22 MEMORANDUM OF EXTRADITION LAW AND REQUEST 23 FOR DETENTION PENDING EXTRADITION PROCEEDINGS 24 25 26 27 28 Case 2:18-mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 2 of 32 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..........................................................................................................1 3 II. LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF EXTRADITION PROCEEDINGS ...................................................2 4 A. The limited role of the Court in extradition proceedings. ....................................................2 5 B. The Requirements for Certification .....................................................................................3 6 1. Authority Over the Proceedings ...........................................................................3 7 2. Jurisdiction Over the Fugitive ..............................................................................4 -

Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g15z7t No online items Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 Finding aid prepared by Performing Arts Special Collections Staff; additions processed by Peggy Alexander; machine readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 PASC 353 1 Title: Roy Huggins papers Collection number: PASC 353 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Physical Description: 20 linear ft.(58 boxes) Date: 1948-2002 Abstract: Papers belonging to the novelist, blacklisted film and television writer, producer and production manager, Roy Huggins. The collection is in the midst of being processed. The finding aid will be updated periodically. Creator: Huggins, Roy 1914-2002 Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Land of Horses 2020

LAND OF HORSES 2020 « Far back, far back in our dark soul the horse prances… The horse, the horse! The symbol of surging potency and power of movement, of action in man! D.H. Lawrence EDITORIAL With its rich equine heritage, Normandy is the very definition of an area of equine excellence. From the Norman cavalry that enabled William the Conqueror to accede to the throne of England to the current champions who are winning equestrian sports events and races throughout the world, this historical and living heritage is closely connected to the distinctive features of Normandy, to its history, its culture and to its specific way of life. Whether you are attending emblematic events, visiting historical sites or heading through the gates of a stud farm, discovering the world of Horses in « Normandy is an opportunity to explore an authentic, dynamic and passionate region! Laurence MEUNIER Normandy Horse Council President SOMMAIRE > HORSE IN NORMANDY P. 5-13 • normandy the world’s stables • légendary horses • horse vocabulary INSPIRATIONS P. 14-21 • the fantastic five • athletes in action • les chevaux font le show IIDEAS FOR STAYS P. 22-29 • 24h in deauville • in the heart of the stud farm • from the meadow to the tracks, 100% racing • hooves and manes in le perche • seashells and equines DESTINATIONS P. 30-55 • deauville • cabourg and pays d’auge • le pin stud farm • le perche • saint-lô and cotentin • mont-saint-michel’s bay • rouen SADDLE UP ! < P. 56-60 CABOURG AND LE PIN PAYS D’AUGE STUD P. 36-39 FARM DEAUVILLE P. -

Retriever (Labrador)

Health - DNA Test Report: DNA - HNPK Gundog - Retriever (Labrador) Dog Name Reg No DOB Sex Sire Dam Test Date Test Result A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S EL TORO AT AV0901389 27/08/2017 Dog BLACKSUGAR LUIS WATERLINE'S SELLERIA 27/11/2018 Clear BALLADOOLE (IMP DEU) (ATCAQ02385BEL) A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S GET LUCKY (IMP AV0904592 09/04/2018 Dog CLEARCREEK BONAVENTURE A SENSE OF PLEASURE'S TEA FOR 27/11/2018 Clear DEU) WINDSOCK TWO (IMP DEU) AALINCARREY PUMPKIN AT LADROW AT04277704 30/10/2016 Bitch MATTAND EXODUS AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE 20/11/2018 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER LOVE AR03425707 19/08/2014 Bitch BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 27/08/2019 Carrier AALINCARREY SUMMER MAGIC AR03425706 19/08/2014 Dog BRIGHTON SARRACENIA (IMP POL) AALINCARREY FAIRY DUST 23/08/2017 Clear AALINCARREY WISPA AT01657504 09/04/2016 Bitch AALINCARREY MANNANAN AFINMORE AIRS AND GRACES 03/03/2020 Clear AARDVAR WINCHESTER AH02202701 09/05/2007 Dog AMBERSTOPE BLUE MOON TISSALIAN GIGI 12/09/2016 Clear AARDVAR WOODWARD AR03033605 25/08/2014 Dog AMBERSTOPE REBEL YELL CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 29/11/2016 Carrier AARDVAR ZOLI AU00841405 31/01/2017 Bitch AARDVAR WINCHESTER CAMBREMER SEE THE STARS 12/04/2017 Clear ABBEYSTEAD GLAMOUR AT TANRONENS AW03454808 20/08/2019 Bitch GLOBETROTTER LAB'S VALLEY AT ABBEYSTEAD HOPE 25/02/2021 Clear BRIGBURN (IMP SVK) ABBEYSTEAD HORATIO OF HASELORHILL AU01380005 07/03/2017 Dog ROCHEBY HORN BLOWER HASELORHILL ENCORE 05/12/2019 Clear ABBEYSTEAD PAGEANT AT RUMHILL AV01630402 10/04/2018 Dog PARADOCS BELLWETHER HEATH HASELORHILL ENCORE -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

The Mammoth Cave ; How I

OUTHBERTSON WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 Mails. Publications : The Mammoth Cave ; D'ACHE, Caran (Emmanuel Poire), cari- How I found the Gainsborough Picture ; caturist b. in ; Russia ; grandfather French Conciliation in the North of Coal ; England ; grandmother Russian. Drew political Mine to Cabinet ; Interviews from Prince cartoons in the "Figaro; Caran D'Ache is to Peasant, etc. Recreations : cycling, Russian for lead pencil." Address : fchological studies. Address : 33 Walton Passy, Paris. [Died 27 Feb. 1909. 1 ell Oxford. Club : Koad, Oxford, Reform. Sir D'AGUILAR, Charles Lawrence, G.C.B ; [Died 2 Feb. 1903. cr. 1887 ; Gen. b. 14 (retired) ; May 1821 ; CUTHBERTSON, Sir John Neilson ; Kt. cr, s. of late Lt.-Gen. Sir George D'Aguilar, 1887 ; F.E.I.S., D.L. Chemical LL.D., J.P., ; K.C.B. d. and ; m. Emily, of late Vice-Admiral Produce Broker in Glasgow ; ex-chair- the Hon. J. b. of of School Percy, C.B., 5th Duke of man Board of Glasgow ; member of the Northumberland, 1852. Educ. : Woolwich, University Court, Glasgow ; governor Entered R. 1838 Mil. Sec. to the of the Glasgow and West of Scot. Technical Artillery, ; Commander of the Forces in China, 1843-48 ; Coll. ; b. 13 1829 m. Glasgow, Apr. ; Mary served Crimea and Indian Mutiny ; Gen. Alicia, A. of late W. B. Macdonald, of commanding Woolwich district, 1874-79 Rammerscales, 1865 (d. 1869). Educ. : ; Lieut.-Gen. 1877 ; Col. Commandant School and of R.H.A. High University Glasgow ; Address : 4 Clifton Folkestone. Coll. Royal of Versailles. Recreations: Crescent, Clubs : Travellers', United Service. having been all his life a hard worker, had 2 Nov. -

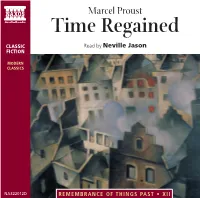

Marcel Proust Time Regained

Marcel Proust Time Regained CLASSIC Read by Neville Jason FICTION MODERN CLASSICS NA322012D REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST • XII 1 At Tansonville with Gilberte 7:37 2 Saint-Loup insisted I should remain… 6:15 3 Years in a sanatorium with a visit to Paris in 1914 4:32 4 At dinner time the restaurants were full… 2:55 5 Occasional meetings with Baron de Charlus 6:19 6 A return to the sanatorium 3:37 7 On my second return to Paris – another letter 3:55 8 A visit from Robert de Saint-Loup 3:18 9 Thinking about Saint-Loup’s visit 7:01 10 A further vendetta against Baron de Charlus 7:49 11 The views of Baron de Charlus 5:24 12 The destruction of men and the effect of the War 6:36 13 The aeroplanes passing through the night sky 7:46 14 Among abandoned, derelict houses,… 4:14 15 Entrance to the house followed by a sailor 2:01 16 A shocking discovery 6:22 17 ‘I implore you, mercy, mercy, have pity’ 2:49 18 A croix-de-guerre had been found on the floor 10:27 19 News of the death of Robert de Saint 10:56 20 Back to another sanatorium 2:44 21 I ordered a carriage to take me to the party 6:43 22 I got down from the carriage again 2:00 2 23 I stumble on some uneven paving stones 4:13 24 I entered the Guermantes’s mansion 3:55 25 I forced myself to try and see clearly 8:52 26 Fragments of existence removed from time 3:27 27 As I entered the Prince de Guermantes’s library 4:02 28 Real life… which has been uncovered… 5:59 29 At this moment, the butler arrived… 6:56 30 The Duchesse de Guermantes: 4:23 31 Old age, the meaning of death 8:03 32 Odette – looking -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Interracial Marriage

How to improve your marriage By studying love and romance in the Bible Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Glenn Pease and Steve Pease ABOUT THIS BOOK Do you have the perfect marriage? Do you ever have problems with your spouse? Do you ever wish they would be different in how they do thing? Do you wish your partner was more like when you met them? Thinking about these questions and your answers will make you think about if things could be better, and how together you can make things great. In this book we will discuss what God says, and what Jesus did, and what Godly men in the Bible did to make their love stronger and their marriages better. Then we will discuss some very easy to do things that you can do to show your partner you love them and that you want them to be happy. You will learn that if you praise your partner, in little things, the big things will go much easier. Almost everyone is in love when they get married, what happens, do we fall out of love? If so why do we fall out of love? Things change when the honeymoon is over and we start living our everyday lives of work and dealing with normal things that happen in life. -

Pacific Health Jourxal - and Temperance Advocate

PACIFIC HEALTH JOURXAL - AND TEMPERANCE ADVOCATE. VOLUME VI. OAKLAND, CAL_ JANUARY, 1891. NUMBER 1. W. P. BURKE, M. D., Editor. RELATIONS OF MIND AND BODY IN EAT- 21 82-P21GE MONTHLYe ING AND DRINKING. SUBSCRIPTION PRICE, : $1.00 PER YEAR. THE soul is the source of many of the wrongs Address.—All business for the JOURNAL should be ad- in human life, but it is not the only source. It is dressed to PACIFIC HEALTH JOURNAL, care of Rural a fact that influences both good and bad pass over Health Retreat, St. Helena, Cal. All Drafts or Money Orders sent in payment of sub- from the mind to the body; certainly it is equally scriptions should be addressed to, and made payable to, true that these same influences pass from the lower Pacific Press, Oakland, Cal. All Communications for the JOURNAL should be ad- to the higher nature. Vicious thoughts, lustful dressed to PACIFIC HEALTH JOURNAL, care of Rural feelings and imaginations go from mind to body Health Retreat, St. Helena, Cal. over the road of unbridled appetites, unrestrained passions, and unsubdued lusts, and the same cor- SHORT SERMONS. rupt feelings and evil imaginations return from THE man who loves his duty never slights it. body to mind over the same road, goading it on A FRIEND is one who hunts you when you are to the wildest conceptions of vice. Evil thoughts lost. and imaginations give inward tone to the body, so the body reacts on the mind, by its appetites and COMMON sense is a hard thing to have too passions, increasing the viciousness of the latter much of.