Chesapeake Bay TMDL Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People, Land, and Water of the Upper Thornton River Watershed: a Model for Countywide Watershed Management Planning

People, land, and water of the Upper Thornton River Watershed: A model for countywide watershed management planning Final Report to the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation RappFLOW Grant #2005-0001-039 Prepared by Beverly Hunter, Project Director [email protected] Phone: 540 937-4038 This report is available in pdf format from www.rappflow.org November 29, 2006 12/18/2006 1 Introduction Rappahannock Friends and Lovers of Our Watershed (RappFLOW) is a group of volunteers founded in the summer of 2002. We work with many partner organizations as well as local leaders, landowners, and other stakeholders to help preserve, protect and restore the watersheds and water quality in Rappahanock County, Virginia. In this report, we provide highlights of the results, lessons learned and progress made from March 2005 through November 2006 in the project “People, land, and water of the Upper Thornton River Watershed: A model for countywide watershed management planning.” This project was funded in part by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, the County of Rappahannock, nonprofit organizations, and private donors. Several state agencies provided technical assistance and training. Rappahannock County is a rural, scenic county with a population of about 7,000 at the headwaters of the Rappahannock River Basin. Seven hundred and fifty-five (755) stream miles in 1,010 stream segments (National Hydrology Database 2005), many on steep slopes, crisscross our land area of about 267 square miles. The northwestern boundary is in the Blue Ridge Mountains, in Shenandoah National Park. The Rappahannock River forms the northeastern boundary with Fauquier County. -

Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware

Upper Ceoozoic Deposits GEOLOGICAL SXJEVilY FRQfEBSIONAL lAPEE Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware By JAMES P. OWENS and CHARLES S. DENNY SURFACE AND SHALLOW SUBSURFACE GEOLOGIC STUDIES IN THE EMERGED COASTAL PLAIN OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1067-A Upper Tertiary deltaic and shallow-water marine deposits form the backbone of the peninsula. The oldest marine deposits of Pleistocene age reach a maximum altitude of 15 meters (50 feet) and have been dated radiometrically at about 100,000 years UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Owens, James Patrick, 1924- Upper Cenozoic deposits of the central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware. (Surface and shallow subsurface geologic studies in the emerged coastal plain of the Middle Atlantic States) (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1067-A) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1067-A 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Cenozoic. 2. Geology Delmarva Peninsula. I. Denny, Charles Storrow, 1911- joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper ; 1067-A. QE690.093 551.7'8 77-608325 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03191-4 CONTENTS Abstract._____________________________________________________________ -

2012-AG-Environmental-Audit.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER AND DEEP CREEK LAKE .................. 4 I. Background .......................................................................................................... 4 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ........................................................... 9 III. The Youghiogheny River/Deep Creek Lake Audit, May 16, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned............................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: COASTAL BAYS ............................................................................. 15 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 15 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ............................................. 17 III. The Coastal Bays Audit, July 12, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned .. 20 CHAPTER THREE: WYE RIVER ................................................................................. 24 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 24 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ......................................................... 26 III. The Wye River Audit, October 10, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned 27 CHAPTER FOUR: POTOMAC RIVER NORTH BRANCH AND SAVAGE RIVER 31 I. Background ....................................................................................................... -

Shoreline Management in Chesapeake Bay C

Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay C. S. Hardaway, Jr. and R. J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary 1 Cover Photo: Drummond Field, Installed 1985, James River, James City County, Virginia. This publication is available for $10.00 from: Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P. O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 356 Virginia Sea Grant Publication VSG-99-11 October 1999 Funding and support for this report were provided by... Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant College Program Sea Grant Contract # NA56RG0141 Virginia Coastal Resource Management Program NA470Z0287 WILLIAM& MARY Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay By C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. and Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1999 4 Table of Contents Preface......................................................................................7 Shoreline Evolution ................................................................8 Shoreline Processes ..............................................................16 Wave Climate .......................................................................16 Shoreline Erosion .................................................................20 Reach Assessment ................................................................23 Shoreline Management Strategies ......................................24 Bulkheads and Seawalls -

Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System

Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System Jason Tercha January 16, 2017 In 1952, the Alexandria City Council created the first sanitation authority in Virginia. Four years later, the City of Alexandria Sewer Authority opened a water-treatment facility near the mouth of Hooff’s Run. Since 1956, the water treatment facility has treated the city’s sewerage discharge, purifying the sanitary water of the city and discharging clean water back into the environment. In response to more stringent environmental standards and renewed efforts to restore the health of the Chesapeake Bay, the Alexandria Sewer Authority upgraded the facility during the late 1990s and through the 2000s. Now known as Alexandria Renew Enterprises after a 2012 rebrand, the sewerage facility remains a crucial component of the city of Alexandria’s efforts to maintain the health and prosperity of its citizens and environment. This brief overview of the city of Alexandria’s twentieth and twenty-first century efforts to manage and treat its sewerage is well documented in city records, newspapers, and the annual reports of the Alexandria Sewer Authority.1 However, as much as these recent efforts to manage waste- and stormwater are known, the city’s earlier struggles to accomplish these goals have largely remained a mystery. The obscurity of Alexandria’s early sewerage control efforts might mistakenly suggest a dearth of water management efforts in the nineteenth century. As this report demonstrates, since the city’s founding Alexandrians exerted immense efforts to manage the excess stormwater and to dispose of the human and animal wastes by incorporating new technologies and practices to respond to evolving knowledge of human health and the environment of a growing regional entrepôt. -

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, VA C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. 1 Donna A. Milligan 1 Lyle M. Varnell 2 Christine Wilcox 1 George R. Thomas 1 Travis R. Comer 1 Shoreline Studies Program 1 Department of Physical Sciences and Wetlands Program 2 Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 This project was funded by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality’s Coastal Resources Management Program through Grant #NA17OZ2355 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies or DEQ. LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Location of the City of Norfolk within the Chesapeake Bay estuarine system...................2 Figure 2. Location of localities in the Dune Act with jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional localities noted. ...2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Figure 3. Geological map of the City of Norfolk (from Mixon et al., 1989). ...........................3 Figure 4. Index of shoreline plates.............................................................4 TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................. i Figure 5. Variability of dune and beach profiles within the City of Norfolk ............................7 Figure 6. Typical profile of a Chesapeake Bay dune system. ........................................7 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................... i Figure 7. Photo of the Norfolk shoreline showing dune site NF3.. ...................................9 Figure 8. -

Garrett County

Appendix D- Recreation Inventory County Acres Private/ quasi-public State/Federal Acres Courts Fields Trails (Miles) Campsites Basketball Basketball Baseball Multi Swimming XC Golf Public Beach Public Boat Site Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Classification Ownership Comments/Amenities Indoor Outdoor Tennis Other Gymnasium Softball Soccer Purpose Pools Skiing Hiking Biking ORV Snowmobile Total Public Pvt Courses (ft.) Launch Areas Accident Community Park East 4.1 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Ball field, walking trail, horseshoe pits 1 1 1 0.25 0.25 Accident Community Park West 12.5 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Pavilions, volleyball Accident Elementary School 9.6 School Recreation Park Board of Education Basketball court, playground 1 1 1 1 Accident Community Pond 2.4 Community Park Town of Accident Fishing pond Aquatic Center 1.0 Marine Private Private marina 1 ASCI -Adventure Sports Center Int'l. 17.0 Special Use Area ASCI Man-made whitewater course Avilton Community Center 2.0 Special Use Area Avilton Community Assoc. Playground, basketball court, pavilion 1 Bear Creek Hatchery Fish Mgmt. Area 113.0 Natural Resource Area State of MD Fish management area Big Run State Park 300.0 State Park State of MD Camping, fishing, Savage River Reservoir access 29 1 Bill's Outdoor Center 1.0 Marine Private Lake access, shoreline Bills Marine Service, Inc. 1.0 Marine Private Marina, boat rentals 1 Bloomington Fire Co. Town Park 3.0 Community Park Bloomington Fire Co. Basketball court, walking trail, pavilion -

The Recreation the Delmarva Peninsula by David

THE RECREATION POTENTIAL OF THE DELMARVA PENINSULA BY DAVID LEE RUBIN S.B., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1965) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOT THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1966 Signature of Author.,.-.-,.*....... .. .*.0 .. .. ...... .. ...... ... Department of City and Regional Planning May 23, 1966 Certified by.... ....... .- -*s.e- Super....... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by... ... ...tire r'*n.-..0 *10iy.- .. 0....................0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 038 The Recreation Potential of the Delmarva Peninsula By David Lee Rubin Submitted to the Department of City and Regional Planning on 23 May, 1966 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning. rhis thesis is a plan for the development of Lne recreation potential of the Delmarva Peninsyla, the lower counties of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, to meet the needs of the Megalopolitan population. Before 1952, the Delmarva Peninsula was isolated, and no development of any kind occurred. The population was stable, with no in migration, and the attitudes were rural. The economy was sagging. Then a bridge was built across the Chesapeake Bay, and the peninsula became a recreation resource for the Baltimore and Washington areas. Ocean City and Rehoboth, the major resorts, have grown rapidly since then. In 1964, the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel further accellerated growth. There are presently plans for the development of a National Seashore on Assateague Island, home of the Chincoteague ponies, as well as state parks along the Chesapeake Bay, and such facilities as a causeway through the ocean and a residential complex in the Indian River Bay. -

Targeted Living Shoreline Management Planning for Virginia State Parks in Chesapeake Bay

Targeted Living Shoreline Management Planning for Virginia State Parks in Chesapeake Bay Summary Report November 2018 Targeted Living Shoreline Management Planning for Virginia State Parks in Chesapeake Bay Summary Report Donna A. Milligan C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. Christine A. Wilcox Shoreline Studies Program Virginia Institute of Marine Science William & Mary This project was funded by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program at the Department of Environmental Quality through Grant # NA17NOS4190152 Task 92.02 of the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, or any of its subagencies. November 2018 Page | 1 1 Introduction The Commonwealth of Virginia owns numerous tidal, waterfront properties along Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries including state parks, natural area preserves, and wildlife management areas. Many of these parks have eroding shorelines and are at risk from coastal hazards such as tidal flooding, waves, and sea level rise. These environmental threats impact the safety of park visitors and the mission of the parks. In an effort to address these issues for the parks as well as provide education to the public on living shoreline management strategies, eleven state parks with tidal shoreline along the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries were selected because of their suitablility for living shoreline demonstration projects (Figure 1). These parks: Belle Isle, Caledon, Chippokes, First Landing, Kiptopeke, Leesylvania, Mason Neck, Middle Peninsula, Westmoreland, Widewater, and York River, are spread throughout the Chesapeake Bay and have a variety of coastal conditions due to their locations and underlying geology. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

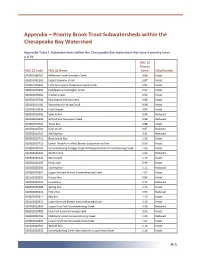

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96