The George Wright Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

1999 Rampart-Lapierre-House-Management-Plan

RAMPART HOUSE HISTORIC SITE LAPIERRE HOUSE HISTORIC SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN MARCH 1999 RAMPART HOUSE HISTORIC SITE LAPIERRE HOUSE HISTORIC SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN PREPARED FOR THE VUNTUT GWITCHIN FIRST NATION And THE GOVERNMENT OF THE YUKON MARCH 1999 PREPARED BY ECOGISTICS CONSULTING BOX 181 WELLS, BC, V0K 2R0 [email protected] voice: (250) 994-3349 fax: (250) 994-3358 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Ecogistics Consulting and the planning team would like to thank the members of the Heritage Committee, the staff of the Heritage Branch of Tourism Yukon, and the staff of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation for the assistance they have provided throughout the project. We would also like to thank the Vuntut Gwitchin Elders and other members of the community of Old Crow and the many people who took the time to come the to public meetings and contribute their thoughts and ideas. People from several different communities took the time to respond to the newsletter and their input is appreciated. Heritage Committee: Dennis Frost Ruth Gotthardt Katie Hayhurst William Josie Doug Olynyk Esau Schafer Planning Team Judy Campbell, Ecogistics Consulting, Senior Planner Eileen Fletcher, Architect and Conservation Specialist Helene Dobrowolsky and Rob Ingram – Midnight Arts, Interpretation Specialists Colin Beaisto, Historian Sheila Greer, Consulting Archaeologist Additional Contributions: Norm Barichello For the younger generation coming up, they want to know where their forefathers came from. Dennis Frost, 1998. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 BACKGROUND ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1.1 The Planning and Public Consultation Process…………………………………………………... 3 1.2 THE PLANNING CONTEXT………………………………………………………………………….. 4 1.2.2 Location and Legal Boundaries…………………………………………………………………... 4 1.2.2 Climate…………………………………………………………………………………………... -

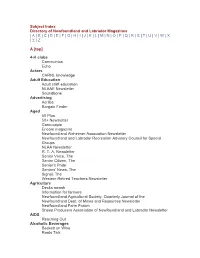

Subject Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador

Subject Index Directory of Newfoundland and Labrador Magazines | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A [top] 4-H clubs Communico Echo Actors CARNL knowledge Adult Education Adult craft education NLAAE Newsletter Soundbone Advertising Ad libs Bargain Finder Aged 50 Plus 50+ Newsletter Cornucopia Encore magazine Newfoundland Alzheimer Association Newsletter Newfoundland and Labrador Recreation Advisory Council for Special Groups NLAA Newsletter R. T. A. Newsletter Senior Voice, The Senior Citizen, The Senior's Pride Seniors' News, The Signal, The Western Retired Teachers Newsletter Agriculture Decks awash Information for farmers Newfoundland Agricultural Society. Quarterly Journal of the Newfoundland Dept. of Mines and Resources Newsletter Newfoundland Farm Forum Sheep Producers Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Newsletter AIDS Reaching Out Alcoholic Beverages Beckett on Wine Roots Talk Winerack Alcoholism Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Foundation of Newfoundland and Labrador. Newsletter Banner of temperance Highlights Labrador Inuit Alcohol and Drug Abuse Program Alternate Alternate press Current Downtown Press Alumni Luminus OMA Bulletin Spencer Letter Alzheimer's disease Newfoundland Alzheimer Association Newsletter Anglican Church Angeles Avalon Battalion bugle Bishop's newsletter Diocesan magazine Newfoundland Churchman, The Parish Contact, The St. Thomas' Church Bulletin St. Martin's Bridge Trinity Curate West Coast Evangelist Animal Welfare Newfoundland Poney Care Inc. Newfoundland Pony Society Quarterly Newsletter SPCA Newspaws Aquaculture Aqua News Cod Farm News Newfoundland Aquaculture Association Archaeology Archaeology in Newfoundland & Labrador Avalon Chronicles From the Dig Marine Man Port au Choix National Historic Site Newsletter Rooms Update, The Architecture Goulds Historical Society. -

The George Wright

THE GEORGE WRIGHT FORUvolume 23 Mnumber 1 * 2006 The ICOMOS-Ename Charter for Cultural Heritage Interpretation Origins Founded in 1980. the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natu ral parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to be the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors DwiGHT T. PlTCMTHLEY, President • Las Cruces, New Mexico ABIGAIL B. MILLER, Vice President • Shelhurne, Vermont JERRY EMORY, Treasurer • Mill Valley, California GILLIAN BOWSER, Secretary • Bryan, Texas REBECCA CONARD • Murfreesboro, Tennessee ROLF DiAMANT • Woodstock, Vermont SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming DAVID J. PARSONS • Florence, Montana STEPHANIE TOOTHMAN • Seattle, Washington WILLIAM H. WALKER,JR. • Herndon, Virginia STEPHEN WOODLEY • Chelsea, Quebec Executive Office DAVID HARMON, Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • fax 1-906-487-9405 [email protected] • www.georgewright.org The George Wright Society is a member of US/ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites—U.S. -

'Deprived of Their Liberty'

'DEPRIVED OF THEIR LIBERTY': ENEMY PRISONERS AND THE CULTURE OF WAR IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1775-1783 by Trenton Cole Jones A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland June, 2014 © 2014 Trenton Cole Jones All Rights Reserved Abstract Deprived of Their Liberty explores Americans' changing conceptions of legitimate wartime violence by analyzing how the revolutionaries treated their captured enemies, and by asking what their treatment can tell us about the American Revolution more broadly. I suggest that at the commencement of conflict, the revolutionary leadership sought to contain the violence of war according to the prevailing customs of warfare in Europe. These rules of war—or to phrase it differently, the cultural norms of war— emphasized restricting the violence of war to the battlefield and treating enemy prisoners humanely. Only six years later, however, captured British soldiers and seamen, as well as civilian loyalists, languished on board noisome prison ships in Massachusetts and New York, in the lead mines of Connecticut, the jails of Pennsylvania, and the camps of Virginia and Maryland, where they were deprived of their liberty and often their lives by the very government purporting to defend those inalienable rights. My dissertation explores this curious, and heretofore largely unrecognized, transformation in the revolutionaries' conduct of war by looking at the experience of captivity in American hands. Throughout the dissertation, I suggest three principal factors to account for the escalation of violence during the war. From the onset of hostilities, the revolutionaries encountered an obstinate enemy that denied them the status of legitimate combatants, labeling them as rebels and traitors. -

From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic

Open Archaeology 2016; 2: 209–231 Original Study Open Access Peter Dawson*, Richard Levy From Science to Survival: Using Virtual Exhibits to Communicate the Significance of Polar Heritage Sites in the Canadian Arctic DOI 10.1515/opar-2016-0016 Received January 20, 2016; accepted October 29, 2016 Abstract: Many of Canada’s non-Indigenous polar heritage sites exist as memorials to the Heroic Age of arctic and Antarctic Exploration which is associated with such events as the First International Polar Year, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the race to the Poles. However, these and other key messages of significance are often challenging to communicate because the remote locations of such sites severely limit opportunities for visitor experience. This lack of awareness can make it difficult to rally support for costly heritage preservation projects in arctic and Antarctic regions. Given that many polar heritage sites are being severely impacted by human activity and a variety of climate change processes, this raises concerns. In this paper, we discuss how virtual heritage exhibits can provide a solution to this problem. Specifically, we discuss a recent project completed for the Virtual Museum of Canada at Fort Conger, a polar heritage site located in Quttinirpaaq National Park on northeastern Ellesmere Island (http://fortconger.org). Keywords: Arctic; Heritage, Fort Conger, Virtual Reality, Computer Modeling, Education, Climate Change, Polar Exploration, Digital Archaeology. 1 Introduction Climate change and the emerging geopolitical significance of the Arctic have important implications for Canada’s polar heritage. In many Arctic regions, thawing permafrost, land subsidence, erosion, and flooding are causing irreparable damage to heritage sites associated with Inuit culture, historic Euro-North American exploration, whaling and the fur trade (Blankholm, 2009; BViikari, 2009; Camill, 2005; Hald, 2009; Hinzman et al., 2005; Morten, 2009; Stendel et al., 2008). -

Recent Climate-Related Terrestrial Biodiversity Research in Canada's Arctic National Parks: Review, Summary, and Management Implications D.S

This article was downloaded by: [University of Canberra] On: 31 January 2013, At: 17:43 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Biodiversity Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tbid20 Recent climate-related terrestrial biodiversity research in Canada's Arctic national parks: review, summary, and management implications D.S. McLennan a , T. Bell b , D. Berteaux c , W. Chen d , L. Copland e , R. Fraser d , D. Gallant c , G. Gauthier f , D. Hik g , C.J. Krebs h , I.H. Myers-Smith i , I. Olthof d , D. Reid j , W. Sladen k , C. Tarnocai l , W.F. Vincent f & Y. Zhang d a Parks Canada Agency, 25 Eddy Street, Hull, QC, K1A 0M5, Canada b Department of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NF, A1C 5S7, Canada c Chaire de recherche du Canada en conservation des écosystèmes nordiques and Centre d’études nordiques, Université du Québec à Rimouski, 300 Allée des Ursulines, Rimouski, QC, G5L 3A1, Canada d Canada Centre for Remote Sensing, Natural Resources Canada, 588 Booth St., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0Y7, Canada e Department of Geography, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada f Département de biologie and Centre d’études nordiques, Université Laval, G1V 0A6, Quebec, QC, Canada g Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E9, Canada h Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada i Département de biologie, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, J1K 2R1, Canada j Wildlife Conservation Society Canada, Whitehorse, YT, Y1A 5T2, Canada k Geological Survey of Canada, 601 Booth St., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0E8, Canada l Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, 960 Carling Ave., Ottawa, ON, K1A 0C6, Canada Version of record first published: 07 Nov 2012. -

Beautiful by Nature !

PRESS KIT Beautiful by Nature ! Bas-Saint-Laurent Gaspésie Côte-Nord Îles de la Madeleine ©Pietro Canali www.quebecmaritime.ca Explore Québec maritime… PRESENTATION 3 DID YOU KNOW THAT… 4 NATIONAL PARKS 5 WILDLIFE OBSERVATION 7 WINTER ACTIVITIES 8 UNUSUAL LODGING 10 GASTRONOMY 13 REGIONAL AMBASSADORS 17 EVENTS 22 STORY IDEAS 27 QUÉBEC MARITIME PHOTO LIBRARY 30 CONTACT AND SOCIAL MEDIA 31 Le Québec maritime 418 724-7889 84, Saint-Germain Est, bureau 205 418 724-7278 Rimouski (Québec) G5L 1A6 @ www.quebecmaritime.ca Presentation Located in Eastern Québec, Québec maritime is made up of the easternmost tourist regions in the province, which are united by the sea and a common tradition. These regions are Bas-Saint-Laurent, Gaspésie, Côte-Nord and the Îles de la Madeleine. A vast territory bordered by 3000 kilometres (1900 miles) of coastline, which alternates between wide fine- sand beaches and small, rocky bays or impressive cliffs, Québec maritime has a long tradition that has been shaped by the ever-present sea. This tradition is expressed in the lighthouses that dot the coast, diverse and abundant wildlife, colourfully painted houses, gatherings on the quays and especially the joie de vivre of local residents. There are places you have to see, feel and experience… Québec maritime is one of them! Did You Know That… The tallest lighthouse in Canada is in Cap-des-Rosiers and is 34 metres (112 feet) high? Jacques Cartier named the Lower North Shore “the land of many isles” because this region’s islands were too numerous to name individually? Lake Pohénégamook is said to hide a monster named Ponik? The Manicouagan impact crater is the fifth largest in the world and can be seen from space? Legendary Percé Rock had three arches in Jacques Cartier’s time? The award winning movie Seducing Dr. -

Fundy National Park

Fundy National Park New Brunswick Fundy Cover: Point Wolfe River with Point Wolfe in background View of McLaren Pond and Bay of Fundy Introducing a Park and an Idea blanket of rock debris called glacial till. It is from this Canada covers half a continent, fronts on three oceans, glacial till that most of the poor, stony soils of Fundy and stretches from the extreme Arctic more than half-way National Park have developed. National Park to the equator. A booklet describing the park's geology in more detail There is a great variety of land forms in this immense can be purchased at the park information office. country, and Canada's national parks have been created to preserve important examples for you and generations The Plants to come. The valleys and rounded hills of Fundy National Park The National Parks Act of 1930 specifies that national are covered with a varied vegetation, dominated by a parks are "dedicated to the people . for their benefit, mixture of broad-leaved and evergreen trees. education and enjoyment," and must remain "unimpaired Within the park are two forest zones. Along the coast, New Brunswick for the enjoyment of future generations." where summers are cool, yellow and white birch are Fundy National Park, 80 square miles in area, skirts scattered among red spruce and balsam fir. The warmer the Bay of Fundy for eight miles and extends inland for plateau is dominated on higher ground by stands of more than nine over a rolling, forested plateau. The sugar maple, beech, and yellow birch, while red spruce, park preserves a superb example of the Bay of Fundy's balsam fir, and red maple thrive in low, swampy areas. -

Gros Morne National Park

DNA Barcode-based Assessment of Arthropod Diversity in Canada’s National Parks: Progress Report for Gros Morne National Park Report prepared by the Bio-Inventory and Collections Unit, Biodiversity Institute of Ontario, University of Guelph December 2014 1 The Biodiversity Institute of Ontario at the University of Guelph is an institute dedicated to the study of biodiversity at multiple levels of biological organization, with particular emphasis placed upon the study of biodiversity at the species level. Founded in 2007, BIO is the birthplace of the field of DNA barcoding, whereby short, standardized gene sequences are used to accelerate species discovery and identification. There are four units with complementary mandates that are housed within BIO and interact to further knowledge of biodiversity. www.biodiversity.uoguelph.ca Twitter handle @BIO_Outreach International Barcode of Life Project www.ibol.org Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding www.ccdb.ca Barcode of Life Datasystems www.boldsystems.org BIObus www.biobus.ca Twitter handle @BIObus_Canada School Malaise Trap Program www.malaiseprogram.ca DNA Barcoding blog www.dna-barcoding.blogspot.ca International Barcode of Life Conference 2015 www.dnabarcodes2015.org 2 INTRODUCTION The Canadian National Parks (CNP) Malaise The CNP Malaise Program was initiated in 2012 Program, a collaboration between Parks Canada with the participation of 14 national parks in and the Biodiversity Institute of Ontario (BIO), Central and Western Canada. In 2013, an represents a first step toward the acquisition of additional 14 parks were involved, from Rouge detailed temporal and spatial information on National Urban Park to Terra Nova National terrestrial arthropod communities across Park (Figure 1). -

A Comparison of National Parks Policy in Canada And

A COMPARISON OF NATIONAL PARKS POLICY IN CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES ' by ROBERT DAVID TURNER B.Sc. , University of Victoria, 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE in The School of Community and Regional Planning We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Community and Regional Planning The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date April 30. 1971 - i - ABSTRACT The history and development of National Park Systems in Canada and the United States are traced over the last 120 years, and the policies determining their management are examined and compared to identify basic similarities and differences. Official government reports and policy statements, historical records, and pertinent books, articles, and bulletins were used as references for the study. Emphasis is placed on recent history and existing policies. It is concluded that the philosophies governing National Parks policy have been, and still are, signifi• cantly different, and as a result, the National Park Systems of the two countries differ both physically and concept• ually. -

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: the role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity edited by A. J. Hails Ramsar Convention Bureau Ministry of Environment and Forest, India 1996 [1997] Published by the Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland, with the support of: • the General Directorate of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of the Walloon Region, Belgium • the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark • the National Forest and Nature Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Energy, Denmark • the Ministry of Environment and Forests, India • the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden Copyright © Ramsar Convention Bureau, 1997. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior perinission from the copyright holder, providing that full acknowledgement is given. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The views of the authors expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the Ramsar Convention Bureau or of the Ministry of the Environment of India. Note: the designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Ranasar Convention Bureau concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: Halls, A.J. (ed.), 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity.