Shopping, Seduction & Mr Selfridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release Tune Into Nature Music Prize Winner

Media Release Tune Into Nature Music Prize Winner LYDIAH selected as recipient of the inaugural Tune Into Nature Music Prize Yorkshire Sculpture Park is delighted to announce the winner of the Tune Into Nature Music Prize, originated by Professor Miles Richardson from the Nature Connectedness Research Group at the University of Derby and supported by Selfridges, Tileyard London and YSP. The winner LYDIAH says: “Becoming the winner of the Tune Into Nature Music Prize has been such a blessing, I’m so grateful to have been given the opportunity. It’s definitely going to help me progress as an artist. Having Selfridges play my track in store and to be associated with such an incredible movement for Project Earth is something that I am very proud of and excited for. I’m able to use the funding to support my debut EP, which couldn’t have come at a better time! The Prize is such a great project and the message is so important. I can’t thank Miles, Martyn and everyone who supports it enough.” Twenty-one year old LYDIAH, based in Liverpool, has been selected as the winner of the Tune Into Nature Music Prize for her entry I Eden. The composition is written from the point of view of Mother Nature and highlights the dangers of humans becoming increasingly distanced from the natural world. LYDIAH will receive a £1,000 grant to support her work, the opportunity to perform at Timber Festival in 2021 and a remix with Tileyard London produced by Principal Martyn Ware (Heaven 17), who says: “I thoroughly enjoyed helping to judge some exceptional entries for this unique competition. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Harry Gordon's

WELCOME TO HARRY GORDON’S BAR Harry Gordon Selfridge was an American retail entrepreneur, born into humble beginnings in Wisconsin in 1856. After leaving school at the age of 14 he began work at a Chicago-based department store in Marshall Field. He was soon nicknamed ‘mile-a-minute Harry’ for his non-stop ideas which saw him work his way from stock boy through to junior partner, marrying heiress Rose Buckingham in 1890 along the way. Harry would regularly travel to Europe on buying trips and in 1906 he moved permanently to London, to found his eponymous Oxford Street store in 1909. His dedication to creating the most extraordinary customer experience is something that lives on at Selfridges today, right down to the service you’ll enjoy here at Harry Gordon’s Bar. Please note that an optional discretionary service charge of 12.5% has been added to your bill. WINES Bottle Sparkling wine & champagne 750ML NV Selfridges Selection Sparkling Rosé, 45.00 Mendoza, Argentina NON VINTAGE NV Selfridges Brut, Henri Giraud 65.00 NV Billecart-Salmon, Brut Reserve 83.00 NV Pol Roger, White Foil, Brut Reserve 86.00 NV Ruinart, Brut 96.00 NV Charles Heidseick, Brut Réserve 98.00 NV Gosset, Grande Réserve 130.00 NV Krug, Grand Cuvée 290.00 Rosé NV Selfridges, Henri Giraud 80.00 NV Charles Heidseick 120.00 NV Billecart-Salmon 125.00 vintage 2009 Pol Roger 180.00 2009 Bollinger, Grande Année 195.00 2009 Dom Pérignon 300.00 2009 Cristal 350.00 WINES Glass Sparkling Wine and champagne 125ML NV Selfridges Selection Sparkling Rosé, 11.00 Mendoza, Argentina Fresh -

Welcome to Harry Gordon's

WELCOME TO HARRy Gordon’s Bar Harry Gordon Selfridge was an American retail entrepreneur, born into humble beginnings in Wisconsin in 1856. After leaving school at the age of 14 he began work at a Chicago-based department store in Marshall Field. He was soon nicknamed ‘mile-a-minute Harry’ for his non-stop ideas which saw him work his way from stock boy through to junior partner, marrying heiress Rose Buckingham in 1890 along the way. Harry would regularly travel to Europe on buying trips and in 1906 he moved permanently to London, to found his eponymous Oxford Street store in 1909. His dedication to creating the most extraordinary customer experience is something that lives on at Selfridges today, right down to the service you’ll enjoy here at Harry Gordon’s Bar. Please note that an optional discretionary service charge of 12.5% has been added to your bill. WINES Bottle Champagne 750ML NON VINTAGE NV Selfridges Brut, Henri Giraud 58.00 NV Chartogne-Taillet, Brut 63.00 NV Billecart-Salmon, Brut Reserve 68.00 NV Pol Roger, White Foil, Brut Reserve 71.00 NV Charles Heidseick, Brut Réserve 75.00 NV Ruinart, Brut 85.00 NV Jacquesson, Cuvée 737 85.00 NV Bollinger, Brut 85.00 NV Gosset, Grande Réserve 93.00 NV Laurent Perrier 95.00 NV Larmandier-Bernier, Blanc de Blancs, 104.00 Terre de Vertus NV Krug, Grand Cuvée 230.00 Rosé 750ML NV Charles Heidseick 88.00 NV Bollinger 90.00 NV Laurent Perrier 95.00 NV Billecart-Salmon 96.00 vintage 750ML 2004 Pol Roger 110.00 2004 Bollinger, Grande Année 145.00 2004 Dom Pérignon 300.00 2006 Cristal 300.00 -

Prophets in Sixteenth Century French Literature by Jessica Singer A

Glimpsing the Divine: Prophets in Sixteenth Century French Literature By Jessica Singer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Timothy Hampton, Chair Professor Déborah Blocker Professor Susan Maslan Professor Oliver Arnold Spring 2017 Abstract Glimpsing the Divine : Prophets in Sixteenth Century French Literature by Jessica Singer Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Timothy Hampton, Chair This project looks at literary representations of prophets from Rabelais to Montaigne. It discusses the centrality of the prophet to the construction of literary texts as well as the material conditions in which these modes of representation were developed. I analyze literature’s appropriation of Hebrew and Classical sources to establish its practices as both independent and politically relevant to the centralizing French monarchy. I propose that prophets are important to the construction of literary devices such as polyphonic discourse, the lyric subject, internal space, and first-person prose narration. The writers discussed in this project rely on the prophet to position their texts on the edge of larger socio-political and religious debates in order to provide a perceptive, critical voice. By participating in a language of enchantment, these writers weave between social and religious conceptualizations of prophets to propose new, specifically literary, roles for prophets. I look at François Rabelais’ prophetic genres – the almanac and the prognostication – in relation to his Tiers livre to discuss prophecy as a type of advice. I then turn to the work of the Pléiade coterie, beginning with Pierre de Ronsard, to argue for the centrality of the prophet to the formation of the lyric subject. -

Shopping, Seduction and Mr Selfridge Pdf Free Download

SHOPPING, SEDUCTION AND MR SELFRIDGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lindy Woodhead | 336 pages | 03 Jan 2013 | Profile Books Ltd | 9781781250587 | English | London, United Kingdom Shopping, Seduction and Mr Selfridge PDF Book I won't give away the end of Selfridge's life tale, but suffice it to say, he was a fascinating, enigmatic man who truly revolutionized the way Americans and Europeans alike shopped. Alan Pell Crawford. A man ahead of his time, an accelerator of change, and he deserves to be remembered as the man who put the fun on to the shop floor and the sex appeal in to shopping. Too energetic and restless to retire, Harry opened up his eponymous department store on London's Oxford Street in His son, Gordon was a playboy and having a wife and children did not stop him when gadding about in society and spending money freely, a trait he came by honestly. Entertaining and educational book! War Work War Play. Refresh and try again. Maybe America was too small for Harry. Franklin and Lucy. His store, which filled nearly a square block, offered restaurants, tea rooms, reading rooms, staff rooms, an ice skating rink and roof top catering and gardens. I was planning on watching the show so I wanted to read the book. Perhaps the upcoming PBS Masterpiece will do just that! He was a kid and Oxford Street, London was his playground. In this book Lindy Woodhead tells the extraordinary story of a revolution in shopping and the rise and fall of a retail prince. Lauren Kessler. The major events of Selfridge's life are woven into the series, with a lot of dramatic fiction thrown in. -

Corporate Governance Statements FY 2019/20 Contents

Selfridges Retail Limited Corporate Governance Statements FY 2019/20 Contents 03 04 12 The Directors and Their The Six Wates Principles Stakeholder Duties under Section and how Selfridges Engagement 172 of the Companies applies these Statement Act 2006 (Section 172) 03 The Directors and Selfridges Retail Limited (Selfridges) is incorporated in the UK and of the Company and its stakeholders, as well as having regard headquartered in London. Selfridges is a world renowned retailer to the requirements of Section 172. This is further developed below. Their Duties under which provides leading luxury shopping experiences for customers Section 172 of the from across the globe; and it is part of the wider ‘Selfridges Group’ Selfridges continues to adopt the Wates Principles for Corporate Companies Act comprised of Selfridges and other international retail businesses. Governance first implemented in 2019, during which year Selfridges 2006 (Section 172) reviewed its internal governance framework to align with good Selfridges has its flagship store on London’s Oxford Street along practice in governance. This included ensuring that there is an with two stores in Manchester at Exchange Square and the Trafford appropriate rhythm for key meetings in Selfridges, with appropriate Centre, as well as another in Birmingham Bullring Centre and also Terms of Reference in place, that attendees’ roles and responsibilities a digital business. These stores are recognised as some of the world’s are considered, meetings are minuted, and matters which should be top retail destinations. Selfridges is renowned for its unique shopping addressed by the board of directors including principal decisions are experiences for both domestic and international customers. -

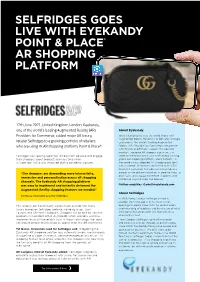

Selfridges Goes Live with Eyekandy Point & Place® Ar

SELFRIDGES GOES LIVE WITH EYEKANDY POINT & PLACE® AR SHOPPING PLATFORM 17th June 2021, United Kingdom, London. Eyekandy, one of the world’s leading Augmented Reality (AR) About Eyekandy Providers for Commerce, added major UK luxury We’re changing the way the world shops with Augmented Reality. Based in London and Chicago, retailer Selfridges to a growing portfolio of retailers Eyekandy is the world’s leading Augmented who are using its AR shopping platform, Point & Place®. Reality (AR) Provider for Commerce. We partner with Brands and Retailers across the world to produce engaging AR shopper experiences in- Selfridges was seeking a partner to help them educate and engage store, online and in print. Our multi award winning, their shoppers about products during a time when global AR shopping Platform, ‘Point & Place®’, is in-store foot traffic was impacted due to pandemic closures. the world’s most adopted AR shopping platform, with hundreds of retailers connected across 30+ countries. Eyekandy has won numerous industry “Our shoppers are demanding more interactivity, awards as we deliver innovation in creative ways to drive sales and engagement from shoppers with immersion and personalisation across all shopping immersive ways to shop and browse. channels. The Eyekandy AR shopping platform was easy to implement and instantly delivered the Further enquiries: [email protected] Augmented Reality shopping features we needed.” About Selfridges Tuf Gavaz, Innovation Lead for Selfridges. In 1906, Harry Gordon Selfridge arrived in London from Chicago with his heart set on The ‘shop in AR’ functionality will be made available for many opening his dream store. With his revolutionary luxury brands on Selfridges website; including Gucci, Saint understanding of publicity and the theatre of retail, Laurent, and Christian Louboutin. -

Mr. Selfridge Starring Jeremy Piven As London’S Merchant Prince on MASTERPIECE CLASSIC Premiering Sunday, March 31, 2013 at 9Pm ET on PBS

Who knew shopping could be like this! Mr. Selfridge Starring Jeremy Piven as London’s merchant prince On MASTERPIECE CLASSIC Premiering Sunday, March 31, 2013 at 9pm ET on PBS Jeremy Piven stars as the upstart American who taught the English how to shop in Mr. Selfridge, a sumptuous new series created by Emmy® Award-winning writer Andrew Davies (Pride and Prejudice, Bleak House), and airing on MASTERPIECE CLASSIC, Sundays, March 31 through May 19, 2013 at 9pm ET on PBS (check local listings). Call The Midwife Season 2 also premieres on March 31 at 8pm. Mr. Selfridge marks the first television role for Piven since his portrayal of movie agentAri Gold in the hit series Entourage. Now, the three-time Emmy® winner tackles another power player in the world of glitz: Harry Gordon Selfridge, father of the renowned London department store that bears his name and which opened to astonishment and some disdain in 1909. Fancy window displays, cosmetics counters, merchandise you can touch, and other marketing breakthroughs had to start somewhere, and they sprang from the genius of Chicago native Selfridge, who combined guile, taste, boldness, the poise of a swindler, and the seductive charm of a Casanova—qualities that spelled success but also trouble. The cast includes Zoe Tapper (Stage Beauty) as Ellen Love, showgirl, temptress, and the sexy “face of Selfridge's”; Frances O’Connor (Madame Bovary) as Rose, Harry’s loyal but independent wife; Grégory Fitoussi (Spiral) as the mercurial Henri LeClair, window designer extraordinaire; and Aisling Loftus (Case Histories) as spunky shop girl Agnes Towler, who gets the lucky break of her life thanks to a chance encounter with Harry. -

London's Skyline and Streetscape Are Undergoing Considerable Change

in LONDONLondon’s skyline and streetscape are undergoing considerable change and Xypex is participating on many of the city’s most visually dominant, award-winning, and culturally important new and revitalised structures. The architects, engineers and contractors of these developments have avidly endorsed Xypex to waterproof, protect and enhance the durability of their buildings’ concrete. in LONDON From the United Kingdom’s tallest building to London’s most luxurious address and a myriad of fascinating structures in-between, Xypex is there, providing products and services to make concrete better. It feels good to be playing a major role in the current construction dynamics of Central London. It’s also rewarding to be rubbing shoulders with some of the world’s finest architects and engineers as they rework the structural form and function of one of western culture’s most famous business hubs. We give a nod to the Romans and the remnants of the original Roman Wall that still define the outer boundaries of Central London, and also a nod to the likes of Dickens and Shakespeare who trod the very paths that today’s creative teams are revitalising. THE SHARD 32 London Bridge Street The Shard, with its church steeple and cladded shards of glass, is the inspiration and design of Renzo Piano, the project’s architect. At 95-storeys and standing 309.6 metres (1,016 ft) high, The Shard (‘Shard of Glass’) is the tallest building in the UK – a top-down construction project that required the largest continuous concrete pour in UK history; three concrete pumps placed 700 truckloads over 36 hours; a total of 5,500 m3. -

10. Rise and Demise of the Department Store

10. Rise and Demise of the Department Store From Humble Beginnings Arguably the world’s first department store was Bennetts of Derby. Opened in 1734 it was initially an ironmonger. Contesting the title was Harding, Howell & Co’s Grand Fashionable Magazine at 89 Pall Mall in St James’s, opening in 1796. Divided into four departments, it offered furs and fans, haberdashery, perfumery, jewellery, clocks, dresses and millinery. The focus was on fashionable and affluent women, with time to browse and money to spend. Trading as Watts Bazaar since 1796 as a drapery in Deansgate, Manchester, Kendal Milne expanded, adding the name Faulkner in 1836. It diversified into cabinet manufacture and upholstery, complete with showrooms. At its height in the 1890s it employed over 900 staff and occupied both sides of the road, linked by an underground passage, ‘Kendal’s Arcade.’ In 1837 James Marshall opened a store at 11 Vere Street, just off Oxford Street, forming a partnership with assistant John Snelgrove in 1848. Three years later a news store opened, on the more prominent corner: the Royal British Warehouse. Changing its name to Marshall & Snelgrove, the firm expanded post World War I to Lancashire and Yorkshire, “cultivating an air of exclusivity” in cities, towns and resorts. Bespoke dressmaking was a speciality. Pride of place for size goes to Bainbridge of Market Street, Newcastle. Opening in 1838, by 1849 it had 23 departments, increasing to 40 by the 1870s. The floor space of 11,705 square yards was slightly larger than 100 yards square, far larger than a football pitch. -

Mr Selfridge Picture Courtesy of ITV Drama of Courtesy Picture

Jeremy Piven as Harry Selfridge and Frances O'Connor as Rose, his wife, in the ITV drama Mr Selfridge Picture courtesy of ITV Drama of courtesy Picture 16 DORSET February 2014 dorsetmagazine.co.uk MR SELFRIDGE Mr Selfridge’s DORSET DREAMS Harry Gordon Selfridge spoiled women in his personal life the same way he did the female customers in his department store. But his love of dance girls, his ostentacious plans and lavish spending in Dorset heralded the start of his sad demise into penury WORDS BY JEREMY MILES PHOTOGRAPHS BY HATTIE MILES illions of viewers and fame. He was a hopeless have been tuning adrenalin junkie, a risk-taker who in for the second always wanted more. While his Mseries of Mr devoted wife Rose and their children Selfridge, the enjoyed the genteel country life in glossy ITV drama about the Highcliffe, Harry would race to town flamboyant self-made American to entertain the glamorous young retail giant who taught the British French singer and dancer Gaby how to love shopping. Deslys. Gaby - one of a series of lovers But how many of them know that - was extremely high-maintenance. Collection' Ian Stevenson 'The of courtesy Picture Harry Gordon Selfridge - the man Harry, who had leased a big Georgian who founded Selfridges department townhouse in Kensington for her, store and coined the phrase “The sent a Selfridges van each day bearing customer is always right” - lived for flowers and gifts. Meanwhile the years right here on the Dorset coast? singer had the run of the Oxford Between 1916 and 1922 he rented the Street store, helping herself to imposing cliff-top Highcliffe Castle whatever took her fancy.