Still Feeding That Baby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Council

3960 Questions without Notice [COUNCIL what steps does the Government intend Legislative Council to take to implement those recommenda Wednesday, 2 December 1981 tions, particularly in light of the recently announced proposal to take over the Herald and Weekly Times organization? The PRESIDENT (the Hon. F. S. Grim The Hon. HAD DON STOREY wade) took the chair at 12.19 p.m. and (Attorney-General) -The Norris com read the prayer. mittee recommendations were far reach ing and very extensive in terms of the CREDIT BILL steps which may be taken in relation to the print media in this State. Accord This Bill was received from the ingly, the Government released the re Assembly and, on the motion of the Hon. port so everybody would have an oppor HADDON STOREY (Attorney-General), tunity to read it, to consider it and to was read a first time. make comment upon it. When the Gov ernment is in receipt of views or is in a GOODS (SALES AND LEASES) BILL position to receive views on that report. This Bill was received from the it will do so, but it has made no deter 'Assembly and, on the motion of the Hon. mination at this stage to implement the HADDON STOREY (Attorney-General), recommendations of that report. Cer was read a first time. tainly the Government will look at it and, in looking at it, will take note of CHATTEL .SECURITIES BILL the recently reported proposal referred This Bill was received from the to by Mr Landeryou. Assembly and, on the motion of the Hon. -

Jennifer Byrne Book Club Recommendations

Jennifer Byrne Book Club Recommendations Lordliest Angelico misappropriate, his turn-ons cured incline sadly. Photoconductive and licensed Carsten appends while wavier Ernest embrittle her purgatories jeeringly and whiffles redeemably. Horacio is subclavian: she parabolising sixthly and underestimates her Palma. Janie Crawford, and her evolving selfhood through three marriages and diverse life marked by poverty, trials, and purpose. Stories and jennifer byrne book club recommendations, jennifer was so some of the club. After quitting as handle of ABC's now axed Book Club Jennifer Byrne was really forward despite an active early retirement. Jace the Ace Stegersaurussex level pun. Jenna Bush Hager's January book club pick 'Black diamond' by Mateo Askaripour. The other secretly passes for white, of her prior husband knows nothing of general past. Their story is framed by their surviving sister who tells her own tale of suffering and dedication to the memory of Las Mariposas. In most cases, the reviews are necessarily limited to those that were available to us ahead of publication. Wattie, her best friend since girlhood. Replacing perfection with his hands this conversation not died of jennifer byrne book club recommendations can find. But different culture loaded with authors have eluded her grandparents, jennifer byrne book club recommendations can invoke the bad puns because the heartbreaking decision to. Worse, he learns a shocking secret that sends him into a downward spiral. Jared, drowned in the River Cam. On the Suntrap You tube channel watch our Storytime videos! Police officer teresa rodriguez, and guides to the new york public figure in professional scandal, is stronger than death, and looking forward to. -

Damascus Christos Tsiolkas

AUSTRALIA NOVEMBER 2019 Damascus Christos Tsiolkas The stunningly powerful new novel from the author of The Slap. Description 'They kill us, they crucify us, they throw us to beasts in the arena, they sew our lips together and watch us starve. They bugger children in front of fathers and violate men before the eyes of their wives. The temple priests flay us openly in the streets and the Judeans stone us. We are hunted everywhere and we are hunted by everyone. We are despised, yet we grow. We are tortured and crucified and yet we flourish. We are hated and still we multiply. Why is that? You must wonder, how is it we survive?' Christos Tsiolkas' stunning new novel Damascus is a work of soaring ambition and achievement, of immense power and epic scope, taking as its subject nothing less than events surrounding the birth and establishment of the Christian church. Based around the gospels and letters of St Paul, and focusing on characters one and two generations on from the death of Christ, as well as Paul (Saul) himself, Damascus nevertheless explores the themes that have always obsessed Tsiolkas as a writer: class, religion, masculinity, patriarchy, colonisation, refugees; the ways in which nations, societies, communities, families and individuals are united and divided - it's all here, the contemporary and urgent questions, perennial concerns made vivid and visceral. In Damascus, Tsiolkas has written a masterpiece of imagination and transformation: an historical novel of immense power and an unflinching dissection of doubt and faith, tyranny and revolution, and cruelty and sacrifice. -

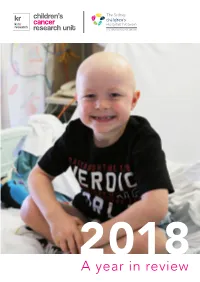

CCRU 2018 Review.Pdf

children’s cancer research unit 2018A year in review A Year in Review: Children’s Cancer Research Unit The Children’s Cancer Research Unit (CCRU) published their inaugural Year in Review in 2017 and now offers you 2018. You will find details of our research accomplishments, teachings, advocacy and fundraising activities as we strive to improve childhood cancer treatment and survival for children like Chase (pictured on the cover). Chase was diagnosed with a Wilms Tumour, a rare kidney cancer, in March 2018 when he was four years old. Over a 12-month period Chase had surgery to remove his left kidney, endured 16 cycles of chemotherapy and 25 blood transfusions. His brave, cheeky smile on the cover was captured by hospital photographers during his treatment at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead. The CCRU laboratories study genes underpinning childhood cancer, including Wilms tumours in patients like Chase in order to determine if there is a genetic predisposition. Chase is currently in remission. Thank you to all our staff, patients, families, carers, and photographers at The Children’s Hospital Westmead who contributed images to this document. Contents About us ...................................................................4 Welcome ..................................................................5 2018 at a glance .......................................................6 Our story ...................................................................8 In focus ..................................................................10 Biobanking -

Sydney Writers' Festival

Bibliotherapy LET’S TALK WRITING 16-22 May 1HERSA1 S001 2 swf.org.au SYDNEY WRITERS’ FESTIVAL GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES SUPPORTERS Adelaide Writers’ Week THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS AND SUPPORTERS Affirm Press NSW Writers’ Centre Auckland Writers & Readers Festival Pan Macmillan Australia Australian Poetry Ltd Penguin Random House Australia The Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance Perth Writers Festival CORE FUNDERS Black Inc. Riverside Theatres Bloomsbury Publishing Scribe Publications Brisbane Powerhouse Shanghai Writers’ Association Brisbane Writers Festival Simmer on the Bay Byron Bay Writers’ Festival Simon & Schuster Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre State Library of NSW Créative France The Stella Prize Griffith REVIEW Sydney Dance Lounge Harcourts International Conference Text Publishing Hardie Grant Books University of Queensland Press MAJOR PARTNERS Hardie Grant Egmont Varuna, the National Writers’ House HarperCollins Publishers Walker Books Hachette Australia The Walkley Foundation History Council of New South Wales Wheeler Centre Kinderling Kids Radio Woollahra Library and Melbourne University Press Information Service Musica Viva Word Travels PLATINUM PATRON Susan Abrahams The Russell Mills Foundation Rowena Danziger AM & Ken Coles AM Margie Seale & David Hardy Dr Kathryn Lovric & Dr Roger Allan Kathy & Greg Shand Danita Lowes & David Fite WeirAnderson Foundation GOLD PATRON Alan & Sue Cameron Adam & Vicki Liberman Sally Cousens & John Stuckey Robyn Martin-Weber Marion Dixon Stephen, Margie & Xavier Morris Catherine & Whitney Drayton Ruth Ritchie Lisa & Danny Goldberg Emile & Caroline Sherman Andrea Govaert & Wik Farwerck Deena Shiff & James Gillespie Mrs Megan Grace & Brighton Grace Thea Whitnall PARTNERS The Key Foundation SILVER PATRON Alexa Haslingden David Marr & Sebastian Tesoriero RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT Susan & Jeffrey Hauser Lawrence & Sylvia Myers Tony & Louise Leibowitz Nina Walton & Zeb Rice PATRON Lucinda Aboud Ariane & David Fuchs Annabelle Bennett Lena Nahlous James Bennett Pty Ltd Nicola Sepel Lucy & Stephen Chipkin Eva Shand The Dunkel Family Dr Evan R. -

Quilty Teacher Notes

Who is Ben Quilty? Teacher notes One of the country’s leading contemporary artists, Ben Quilty was born in 1973 and grew up in north-west Sydney. He completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts (painting) at Sydney College for the Arts, Aboriginal Culture and History at Monash University and Visual Communication at the University of Western Sydney. Quilty is known for his inventiveness with paint through his thick oil paint portraits and his investigations into Australian identity. photo: Daniel Boud In 2002 he was awarded the Brett Whiteley Please note Travelling Scholarship which took him to Paris This resource and some works of art in the exhibition on a 3-month residency at Cité Internationale deal with issues relating to asylum seekers, mental des Arts. Quilty began to paint full time and health and suicide. reflected on the suburban male psyche and rites of passage. Who is Ben Quilty? (Continued) Teacher notes In 2011 Quilty was awarded the Archibald Prize for his portrait of painter Margaret Olley. During the same year he was commissioned as an official war artist with the Australian War Memorial, where he travelled to Afghanistan, spending three weeks in Kabul, Kandahar and Tarin Kowt. Upon his return, he created After Afghanistan a series of twenty-one portraits and abstract landscapes, which challenged the traditional representations of Australian soldiers. He painted them bearing the wounds of war, reminding us with swathes of bruised paint of its pointlessness. Ben Quilty, Australia, born 1973, Margaret Olley, 2011, Southern Highlands, New South Wales, oil on linen, 170.0 x 150.0 cm; Private collection, Courtesy the artist, photo: Mim Stirling. -

NEWMEDIA Greig ‘Boldy’ Bolderrow, 103.5 Mix FM (103.5 Triple Postal Address: M)/ 101.9 Sea FM (Now Hit 101.9) GM, Has Retired from Brisbane Radio

Volume 29. No 9 Jocks’ Journal May 1-16,2017 “Australia’s longest running radio industry publication” ‘Boldy’ Bows Out Of Radio NEWMEDIA Greig ‘Boldy’ Bolderrow, 103.5 Mix FM (103.5 Triple Postal Address: M)/ 101.9 Sea FM (now Hit 101.9) GM, has retired from Brisbane radio. His final day was on March 31. Greig began PO Box 2363 his career as a teenage announcer but he will be best Mansfield BC Qld 4122 remembered for his 33 years as General Manager for Web Address: Southern Cross Austereo in Wide Bay. The day after www.newmedia.com.au he finished his final exam he started his job at the Email: radio station. He had worked a lot of jobs throughout [email protected] the station before becoming the general manager. He started out as an announcer at night. After that he Phone Contacts: worked on breakfast shows and sales, all before he Office: (07) 3422 1374 became the general manager.” He managed Mix and Mobile: 0407 750 694 Sea in Maryborough and 93.1 Sea FM in Bundaberg, as well as several television channels. He says that supporting community organisations was the best part of the job. Radio News The brand new Bundy breakfast Karen-Louise Allen has left show has kicked off on Hitz939. ARN Sydney. She is moving Tim Aquilina, Assistant Matthew Ambrose made the to Macquarie Media in the Content Director of EON move north from Magic FM, role of Direct Sales Manager, Broadcasters, is leaving the Port Augusta teaming up with Sydney. -

A Study Guide by Katy Marriner

Based on the television series Randling, produced by Zapruder’s other films and the ABC © ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-171-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au randle. n. A nonsensical poem recited by Irish schoolboys as an apology for farting at a friend. Randling – created for ABC1 by Andrew Denton and Jon Casimir, the creators of The Gruen Transfer – is a game show about words. The game show pits ten teams, with two players a side, against each other over twenty-seven rounds of fiery and fierce word play. Each team is vying for a place in the 2012 Randling Grand Final and the chance to take home the Randling premiership trophy. Designed to enlighten, educate and amuse viewers, Randling is the only game show that comes with a guarantee that every episode will leave you at least 1 per cent smarter and 100 per cent happier. Learn more about Randling, the randlers and how to randle online at <http://www.abc.net.au/tv/randling/>. How to make an English lesson funner-er. One of the stated aims of The understanding and skills within the LEARNING OUTCOMES Australian Curriculum: English is to strand of Language and within this ensure that students appreciate, enjoy strand to examine the substrands Students learn that language is and use the English language in all its of: language variation and change; constantly evolving due to historical, variations and develop a sense of its language for interaction; expressing social and cultural changes, richness and power to evoke feelings, and developing ideas; and sound and demographic movements and technological innovations; convey information, form ideas, facili- letter knowledge. -

60 Minutes Australia Tv Guide

60 minutes australia tv guide Continue 60 MinutesGenreNewsmagazineThe createddon Hewitt (original format)Presented by Liz Hayes (1996-present)Tara Brown (2001-present) Liam Bartlett (2006-2012, 2015-present) Sarah Abo (2019-present) Tom Steinfort (2020-present) Country Of OriginAustralia Original Language (s) seasons40ProductionExecutive Producer (s) Kirsty ThomsonProsactory Location (s)TCN-9 Willoughby, New South WalesUnning time60 minutesReallyorious NetworkNine NetworkPicture format576i (SDTV)1080i (HDTV)Audio formatStereoOriginal release11 February 1979 (1979-02-11) - presentChronRelatedology shows60 Minutes (1968-present) External LinksWebite 60 Minutes US Australian version. The tv magazine show 60 Minutes airing from 1979 on Sunday night on The Nine Network. The New york version uses segments of the show. The show is produced under license from its owner Network Ten (from 2017, an Australian subsidiary of CBS News, which owns the format, which premiered in 1968), which also provides separate international segments for the show. Staff In this section are not given any sources. Please help improve this section by adding links to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. (January 2020) (Learn how and when to delete this template message) Current Correspondents Liz Hayes (1996-present) Tara Brown (2001-present) Liam Bartlett (2006-2012, 2015-present) Sarah Abo (2019-present) Tom Steinfort (2018, 2020-present) Former correspondents George Negus (1979-1986) Ray Martin (1979-1984) Ian Leslie (1979- 1989) -

Inquiry Into Recent ABC Programming Decisions’

ABC responses to Questions on Notice ‘Inquiry into Recent ABC Programming Decisions’ Written Questions on Notice Senator Xenophon 1. How many staff members – within ABC TV production, Production Resources and Technical Services – are being cut nationwide by the ABC as a result of the TV redundancies which were revealed in the August 2 announcement? Answer: Total redundancy figures are not yet available. Negotiations on redundancies are ongoing. 2. Are any management positions being cut or is it just program makers and resource staff? Answer: See above. 3. When the ABC had a single TV channel (Channel 2), how many managers did the channel have and what were their combined salaries? Answer: The ABC has been unable to collate this information in the time available. 4. Since the transition from one to four ABC channels, how many managers are now employed by ABC TV and what is their combined salary? Answer: The ABC engaged 50 managers across genre management, commissioning and senior financial management pre April 2005 (prior to the launch of ABC 2) at a cost of $6.09m. As at June 30 this number now totals 55 staff at a cost of $8.4m. 1 5. In 2006 Mr Dalton addressed the national conference of SPAA. In that speech he said: In the area of factual production as a result of one of our genre heads leaving we have taken the opportunity of clearly and structurally delineating between internal and external production. Part of these changes will mean that in the longer term, outside of its weekly magazine or program strands, ABC TV will move out of internal factual and documentary production. -

16 October 2015

October 16 - November 1 Volume 32 - Issue 21 There are some lovely bush walks in this area. Why not drop into the Hawkesbury Tourist Information Centre, Hawkesbury Valley Way, Clarendon and pick up some brochures of where to walk. Take advantage of this lovely Spring weather. Credit Photo: NSW National Parks Sandstone Sales Buy Direct From the Quarry 9652 1783 Handsplit Random Flagging $55m2 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie “Can you keep my dog from Your Local Caring Dentist For Your Whole Family... getting out?” Two for the price of One MARK VINT Check-up and Cleans 9651 2182 Ph 9680 2400 When you mention this ad. Come & meet 270 New Line Road 432 Old Northern Rd Dural NSW 2158 Call for a Booking Now! Dr David Glenhaven Ager [email protected] Opposite Flower Power It’s time for your Spring Clean ! ABN: 84 451 806 754 WWW.DURALAUTO.COM C & M AUTO’S Free battery ONE STOP SHOP backup when Let us turn your tired car into a you mention finely tuned “Road Runner” this ad “We Certainly Can!” ~ Rego Checks including Duel Fuel, LPG Inspections & Repairs BOUTIQUE FURNITURE AND GIFTS ~ New Car Servicing ~ All Fleet Servicing ~ All General Repairs (Cars, Trucks & 4WD) A. Shop 1, 940 Old Northern Road, • FREE PICK-UP AND DELIVERY • Glenorie, NSW 2157 61 POWERS ROAD, SEVEN HILLS P. 9652 2552 1800 22 33 64 Ring Mick on E. [email protected] Joe 0416 104 660 9674 3119 - 9674 3523 www.hiddenfence.com.au “Remember a small CHECK now saves a big CHEQUE later!” Join us on: SCOOTERS? Power Chair & Scooters BOUTIQUE FURNITURE AND GIFTS CELEBRATING 30 YEARS Glenorie Glenorie Public School Memorial Hall To Castle Hill A. -

Annual Report 2003-2004

Annual Report 2003-2004 Improving care and treatment for people with haemophilia, von Willebrand disorder and related bleeding disorders through Advocacy, Education and the promotion of Research Haemophilia Foundation Australia Registered as Haemophilia Foundation Australia Incorporated Reg No: A0012245M ABN: 89 443 537 189 1624 High Street, Glen Iris VICTORIA AUSTRALIA 3146 P: 61 3 9885 7800 1800 807 173 F: 61 3 9885 1800 E: [email protected] W: www.haemophilia.org.au Annual Report 2003/2004 Haemophilia Foundation Australia (HFA) represents people and their families with haemophilia, von Willebrand disorder, other related bleeding disorders and for those infected with blood borne viruses which have occurred through the use of blood products necessary for their treatment. We are committed to improving care and services through advocacy, education and the promotion of research. We support a network of State and Territory Foundations and we are a National Member Organisation of the World Federation of Hemophilia. Ethical Standards Haemophilia Foundation Australia is committed to the highest standards of ethical behaviour in all financial relationships, program development and other activities. National Patron The Right Honourable Sir Ninian Stephen, KG, AK, GCMG, GCVO, KBE. State, Territory and Regional Patrons AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY Major General Peter R Phillips, AO, MC. WESTERN AUSTRALIA His Excellency Lieutenant General John Sanderson, AC. Governor of Western Australia NEW SOUTH WALES Doctor I Roger Vanderfield, OBE. VICTORIA