Pop Music As a Possible Medium in Secondary Education (1966)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

BEACH BOYS Vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music

The final word on the Beach Boys versus Beatles debate, neglect of American acts under the British Invasion, and more controversial critique on your favorite Sixties acts, with a Foreword by Fred Vail, legendary Beach Boys advance man and co-manager. BEACH BOYS vs BEATLEMANIA: Rediscovering Sixties Music Buy The Complete Version of This Book at Booklocker.com: http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/3210.html?s=pdf BEACH BOYS vs Beatlemania: Rediscovering Sixties Music by G A De Forest Copyright © 2007 G A De Forest ISBN-13 978-1-60145-317-4 ISBN-10 1-60145-317-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Printed in the United States of America. Booklocker.com, Inc. 2007 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY FRED VAIL ............................................... XI PREFACE..............................................................................XVII AUTHOR'S NOTE ................................................................ XIX 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD 1 2. CATCHING A WAVE 14 3. TWIST’N’SURF! FOLK’N’SOUL! 98 4: “WE LOVE YOU BEATLES, OH YES WE DO!” 134 5. ENGLAND SWINGS 215 6. SURFIN' US/K 260 7: PET SOUNDS rebounds from RUBBER SOUL — gunned down by REVOLVER 313 8: SGT PEPPERS & THE LOST SMILE 338 9: OLD SURFERS NEVER DIE, THEY JUST FADE AWAY 360 10: IF WE SING IN A VACUUM CAN YOU HEAR US? 378 AFTERWORD .........................................................................405 APPENDIX: BEACH BOYS HIT ALBUMS (1962-1970) ...411 BIBLIOGRAPHY....................................................................419 ix 1. THIS WHOLE WORLD Rock is a fickle mistress. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

L-G-0003552750-0006830598.Pdf

GATHERED FROM COINCIDENCE __________________________________________ A singular history of Sixties’ pop by Tony Dunsbee Copyright © Tony Dunsbee 2014. All Rights Reserved An M-Y Books Production m-ybooks.co.uk Take what you have gathered from coincidence “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” – Bob Dylan (© 1965 Warner Bros. Inc., renewed 1993 by Special Rider Music) To my wife Nicky, with love and thanks for her patience and belief in my ability to give at least this much semblance of form and meaning to a lifetime’s obsession. Contents Chapter 1 The Intro … 5 Chapter 2 1960 14 Chapter 3 1961 36 Chapter 4 1962 61 Chapter 5 1963 95 Chapter 6 1964 158 Chapter 7 1965 246 Chapter 8 1966 355 Chapter 9 1967 464 Chapter 10 1968 560 Chapter 11 1969 615 Chapter 12 … and The Outro 678 Acknowledgements 684 Bibliography 686 Index 711 5 Chapter 1 The Intro … This may or may not turn out to be the book in my head but I’m still driven, even now in retirement, to write it by my undimmed passion for the music of the Sixties and a desire to set – no pun intended – the record straight. The one and only record? Well, all right then, by no means, but informed by my ambition to set down my record of the interweaving of the events of those tumultuous years and the impact of the music made in parallel to them, as I lived through the decade then and as I recall it now. Make no mistake, then: this is unashamedly a highly selective rather than a comprehensive account, dictated wholly by my own personal tastes and interests as they were shaped and developed by the consecutive twists and turns of the era. -

The Pirates and Pop Music Radio

SELLING THE SIXTIES Was pirate radio in the sixties a non-stop psychedelic party – an offshore discothèque that never closed? Or was there more to it than hip radicalism and floating jukeboxes? From the mavericks in the Kings Road and the clubs ofSohotothemultinationaladvertisers andbigbusiness boardrooms Selling the Sixties examines the boom of pirate broadcasting in Britain. Using two contrasting models of unauthorized broadcasting, Radios Caroline and London, Robert Chapman situates offshore radio in its social and political context. In doing so, he challenges many of the myths which have grown up around the phenomenon. The pirates’ own story is framed within an examination of commercial precedents in Europe and America, the BBC’s initial reluctance to embrace pop culture, and the Corporation’s eventual assimilation of pirate programming into its own pop service, Radio One. Selling the Sixties utilizes previously unseen evidence from the pirates’ own archives, revealing interviews with those directly involved, and rare audio material from the period. This fascinating look at the relationship between unauthorized broadcasting and the growth of pop culture will appeal not only to students of communications, mass media, and cultural studies but to all those with an enthusiasm for radio history, pop, and the sixties. Robert Chapman’s broadcasting experience includes BBC local radio in Bristol and Northampton. He has also contributed archive material to Radios One and Four. He is currently Lecturer and Researcher in the Department of Performing Arts and Media Studies at Salford College of Technology. Selling the Sixties THE PIRATES AND POP MUSIC RADIO ROBERT CHAPMAN London and New York First published 1992 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge a division of Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc. -

Absence and Presence: Top of the Pops and the Demand for Music Videos in the 1960S

Absence and Presence: Top of the Pops and the demand for music videos in the 1960s Justin Smith De Montfort University Abstract Whilst there is a surprising critical consensus underpinning the myth that British music video began in the mid-1970s with Queen’s video for ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’, few scholars have pursued Mundy’s (1999) lead in locating its origins a decade earlier. Although the relationship between film and the popular song has a much longer history, this article seeks to establish that the international success of British beat groups in the first half of the 1960s encouraged television broadcasters to target the youth audience with new shows that presented their idols performing their latest hits (which normally meant miming to recorded playback). In the UK, from 1964, the BBC’s Top of the Pops created an enduring format specifically harnessed to popular music chart rankings. The argument follows that this format created a demand for the top British artists’ regular studio presence which their busy touring schedules could seldom accommodate; American artists achieving British pop chart success rarely appeared on the show in person. This frequent absence then, coupled with the desire by broadcasters elsewhere in Europe and America to present popular British acts, created a demand for pre-recorded or filmed inserts to be produced and shown in lieu of artists’ appearance. Drawing on records held at the BBC’s Written Archives and elsewhere, and interviews with a number of 1960s music video directors, this article evidences TV’s demand-driver and illustrates how the ‘pop promo’, in the hands of some, became a creative enterprise which exceeded television’s requirement to cover for an artist’s studio absence. -

The Age of Television Innovative TV and Radio Formats

1950s The age of television In 1950 there were 12 million radio-only licences and only 350,000 combined radio and TV licences.The budget for BBC Television was a fraction of the Radio budget. But a single event transformed the popularity of television. This was the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II on June 2, 1953 in Westminster Abbey. Permission had never been given before for television cameras in the Abbey. Some even felt it was wrong for people to watch such a solemn occasion while drinking tea in their front rooms. An estimated 20 million TV viewers saw the young Queen crowned, most of them outside their own homes. This was a turning point and the first time that a television audience exceeded the size of a radio audience. So today The Queen will ascend the steps of her throne… in the sight today of a great multitude of people. Richard Dimbleby, Coronation commentary By 1954 there were well over three million combined sound and vision licences. The television age had arrived and in 1955 the Queen broadcast her Christmas Message on television for the first time. The mid-Fifties introduced some major TV names of the future, including David Attenborough (Zoo Quest 1954), Eamonn Andrews (This Is Your Life 1955) and Jack Warner (Dixon of Dock Green 1955). Drama successes such as The Quatermass Experiment and the controversial adaptation of Nineteen Eighty Four became talking points all over the country. In September 1955 the BBC’s broadcasting monopoly came to an end when ITV was launched. The impact of competition had an instant impact on BBC Television and its share of the audience fell as low as 28% in 1957. -

DPQL: Quiz Quesfions October 14 2015

DPQL: Quiz Questions October 14 2015 DPQL: Quiz Questions October 14 2015 Individual Round 1 1. In astronomy an ‘event horizon’ surrounds which kind of region? Black Hole 2. Which fabric derived its name from a Syrian city? Damask (Damascus) 3. Which playwright wrote The Norman Conquests trilogy? Alan Ayckbourn 4. Which former prime minister’s wife shares her first name with a Bellini opera? (John) Major ‘Norma’ 5. Who was the first Englishman to win the Formula One Drivers Championship? Mike Hawthorn 6. Which Chinese philosophical system translates into English as ‘Wind – Water’? Feng Shui 7. The winner’s trophy at the men’s PDC darts World Championship is named after whom? Sid Waddell 8. What are the water buses or water taxi’s in Venice called? Vaporetto 9. Which God rode an eight-legged horse called Sleipnir? Odin 10. The small buckwheat pancakes called blini are most closely associated with the cuisine of Russia which country? Team Round 2 1. TV Music Shows a) Which 15-minute show introduced by Kent Walton from 1956 was the first regular pop show on UK TV? Cool For Cats b) Who made up the panel on Juke Box Jury on the only occasion it had 5 members not 4? The Rolling Stones c) Which 70s/80s show opened with an animated male figure known as ‘The Star Kicker’? The Old Grey Whistle Test 2. Food a) What kind of dish is the French ‘pithivier’? A Pie b) Which herb is commonly used to flavour the tomato on pizza toppings? Oregano c) Which two colours traditionally make up the quarters on a Battenberg cake? Pink & Yellow 3. -

The Beatles Story Learning Resource Pack

THE BEATLES STORY LEARNING RESOURCE PACK A Comprehensive Guide for Key Stage 1 and 2 www.beatlesstory.com Britannia Vaults, Albert Dock, Liverpool L3 4AD Tel: +44 (0)151 709 1963 Fax: +44 (0)151 708 0039 E-mail: [email protected] CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Booking your visit 3 Learning Aims, Objectives and Outcomes 4 History at Key Stage 2 6 Art at Key Stage 2 7 Discovery Zone Curriculum Links at KS2 11 Political, Economic and Social Influences 1940 – 1950 13 Political, Economic and Social Influences 1950 – 1960 15 Influences on Popular Music of the 1960’s 17 Beatles Time Line 18 John Lennon Fact Sheet 19 Paul McCartney Fact Sheet 20 George Harrison Fact Sheet 21 Ringo Starr Fact Sheet 22 Suggested Classroom Activities - Ideas for History 23 Suggested Classroom Activities - Ideas for Music 24 Suggested Classroom Activities - Ideas for Literacy 25 Suggested Classroom Activities - Ideas for Art 26 Worksheets A-D 37 Geography: River Walk Map KS1 and KS2 40 Pre-Visit Quiz 41 Post-Visit Quiz 42 The Beatles’ Discography 1962 - 1970 tel:0151 709 1963 www.beatlesstory.com INTRODUCTION Located within Liverpool’s historic Albert Dock, We have linked the story of the Beatles, their the Beatles Story is a unique visitor attraction early lives, their fame and combined creativity that transports you on an enlightening and to selected areas of the National Curriculum: atmospheric journey into the life, times, culture history, literacy, art and music to actively and music of the Beatles. encourage and involve children in their own learning. Since opening in 1990, the Beatles Story has continued to develop our learning resources to Whether your school follows established create a fun and educational experience for all. -

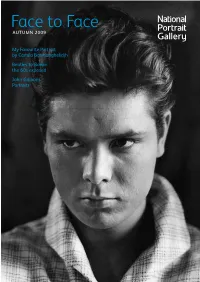

Face to Face Issue 30

2573 Face to Face Autumn:A4 6/8/09 12:36 Page 1 Face to Face AUTUMN 2009 My Favourite Portrait by Camila Batmanghelidjh Beatles to Bowie: the 60s exposed John Gibbons: Portraits 2573 Face to Face Autumn:A4 6/8/09 12:36 Page 2 From the Director In this issue of Face to Face, we are delighted that Camila Batmanghelidjh, founder of the special charity the Kids Company, has chosen her favourite portrait from the Gallery’s Collection. This comes after the unveiling of a special commissioned portrait of Camila undertaken by Dean Marsh, winner of the BP Portrait Award in 2005, and currently on display in Room 40 in the Lerner Galleries. With the opening of the successful Gay Icons exhibition (on show until 18 October), I am pleased that three of the selectors – Ben Summerskill, Lord Waheed Alli and Jackie Kay – have chosen to talk about their personal experiences of being involved with the exhibition. In October, the Gallery opens Beatles to Bowie: the 60s exposed. This major photographic ABOVE exhibition will feature over 150 images from the 1960s including rare portraits of The Cliff Richard Beatles, David Bowie, Jimi Hendrix and The Rolling Stones – with more than 100 prints by Cornel Lucas, 1960 exhibited for the first time. This exhibition will document the critical role that music © Cornel Lucas had on the formation of internationally acknowledged ‘Swinging London’ as well as the This work will feature in Beatles broader development of culture and society in Britain. The exhibition also charts the to Bowie: the 60s exposed on progress of fashion and the cross-over into design and the new world of pop magazines. -

Concerto and Aria Concert May 14 & 15, 2021 7:00 P.M

Concerto and Aria Concert May 14 & 15, 2021 7:00 p.m. Online MacPhail Center for Music MacPhail Center for Music is a nonprofit organization providing life-changing music learning experiences to people of all ages and backgrounds. MacPhail connects with more than 60,000 people in our community annually, through music instruction, community partnerships and performance events. PROGRAM Friday, May 14, 2021 Violin Concerto in A minor, BWV 1041...................................................................................................................Johann Sebastian Bach I: Allegro II: Andante III: Allegro assai Eira Lindberg, violin Student of Mark Bjork Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37................................................................................................................Ludwig van Beethoven I: Allegro con brio Jackson Trom, piano Student of Suzanne Greer “Dove sono I bei momenti” from Le Nozze di Figaro (“The Marriage of Figaro”)............................Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Shannon Braun, voice Student of Mikyoung Park Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11...............................................................................................................................Frédéric Chopin Jessica Shao, piano Student of Jose Uriarte Saturday, May 15, 2021 Piano Concerto No. 20 in D minor, K. 46........................................................................................................Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart I: Allegro Christian Garner, piano Student of Suzanne Greer “Hello!