Noun Cases in the Language of the Sino-Mongol Glossary Dada Yu/Beilu Yiyu from the Late Ming Period

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Good Grinding Wise Dining

Good Grinding for Wise Dining 24 Quick Food & Nutrition Lessons Funded by: State of Hawaii Executive Office on Aging In collaboration with: University of Hawaii College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (UHCTAHR) Cooperative Extension Services (CES) Nutrition Education for Wellness (NEW) program Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program - Education (SNAP-Ed) http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/NEW/GG Sponsors & Collaborators Executive Office on Aging Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Department of Human Services County of Hawaii City and County of Honolulu County of Kauai County of Maui Alu Like Lanakila Meals-On-Wheels Contact Information Nutrition Service for Older Adults 1955 East-West Road #306 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Phone: (808) 956-4124 Fax: (808) 956-6457 Table of Contents Good Grinding for Wise Dining Table of Contents Page Instructor Guide Introduction 7 How to Use This Manual 11 Presentation tips 13 Strategies for Eating: Lessons 1 - 6 *Lesson 1: Easy Meals - “No cook cooking” 15 Tally Sheet 21 Handout (In Sheet Protector) Lesson 2: Sharing Meals – “Sharing is caring” 23 Tally Sheet 27 Handout (In Sheet Protector) Lesson 3: Food Storage – “No need, no buy” 29 Tally Sheet 33 Handout (In Sheet Protector) *Lesson 4: One-Pot Meals – “One pot hits the 35 spot” Tally Sheet 41 Handout (In Sheet Protector) Lesson 5: Microwave Meals – “Time is what we 43 save when we microwave” Tally Sheet 49 Handout (In Sheet Protector) Lesson 6: Meals In Minutes – “Do little steps 51 ahead and we’ll be quickly fed” Tally Sheet 57 Handout -

From Animal to Name, Remarks on the Semantics of Middle Mongolian Personal Names

Volker Rybatzki University of Helsinki From animal to name, remarks on the semantics of Middle Mongolian personal names In 2006 I published my dissertation, “Die Personennamen und Titel der mit- telmongolischen Dokumente: Eine lexikalische Untersuchung”, in the series of the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Helsinki (Publications of the In- stitute for Asian and African Studies 8).1 At that time, I planned to publish in the near future a revised version of the work (together with additional chapters on semantics, word formation, etc.). As it happened, however, a great quantity of new material of Middle Mongolian (including numerous personal names and titles) was published at that time: the materials discovered in Dunhuang at the end of the 1990s and at the beginning of the new millennium (Peng & Wang 2000, 2004a–b), as well as the materials found in Qaraqoto and preserved in Huhhot (Yoshida & Cimeddorji 2008), this last publication includes also some unique Middle Mongolian fragments e.g. hPags-pa written in cursive script. At this point, a revised publication would have meant rewriting the whole disserta- tion; for that reason, the whole plan was abandoned. Other research interests also led to this decision. Already partly written, however, were some sections of the revised version: a treatment of semantics and word formation, an overview of Middle Mongolian literature (in its broadest sense), and an additional chapter dealing with the names of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and other Buddhist entities. As I believe that these chapters might still be of some interest to the scientific world, I hereby present the chapter on the semantics of Middle Mongolian per- sonal names as a token of gratitude to my teacher Juha Janhunen. -

Exclusive Menu

SALAD Seasonal healthy salad Rs. 1,288 Mixed green lettuce, carrot, rocket, orange, black olives tomato, lemon-oregano dressing, balsamic reduction, chia pumpkin seeds and pickled onion CAESAR SALAD Romaine lettuce, pancetta bacon, soft boiled egg, crouton caesar dressing and parmesan shavings Plain Rs.2,288 Deviled chicken croquet Rs.2,688 Smoked seer Rs.2,488 All prices are inclusive of service charge and government taxes. Chef’s Recommenda�on Vegetarian Dishes I’m HUNGRY... FEED ME! MAINS Meat & nut Rs. 2,488 Beef, Thai massaman, peanuts, sweet potato, roasted garlic ricotta cheese and coconut rice Lamb shank Rs. 3,688 Low and slow lamb shank, tomato, intense pepper, red onion and savoury onion mash Tuscan & salmon Rs. 3,288 Slow baked salmon, green ramsons pesto, spinach and sun-dried tomato Bull & vino Rs. 2,488 Slow braised Aus beef, vegetables, rosemary and toasted ciabatta Spaghetti as szechuan Rs. 2,488 Prawn, red chili, garlic, shallot, lime, parsley and basil oil Lasagna de matta Rs. 2,588 Open face sheet, braised Aus beef, ricotta cheese, parmigiana smoked peas and fried egg Meat chop chop xxl (3 feet to share) Rs. 9,888 Cajun chicken, beef steak, pork bbq ribs, devilled chicken wings, pork bratwurst, wedges, salad bowl, curry slaw, pizza bread and sauces Fish chop chop xxl (3 feet to share) Rs.11,888 Banana leaf whole fish, spicy battered shrimps, devilled cuttlefish wings, swordfish steak, shoe lobster, potato wedges, salad bowl, curry slaw, pizza bread and dips GRIDDLE & FIRE Lamb chops 280 gram Rs. 5,288 Prime beef rib eye 250 gram Rs. -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

Local Board Hearing Information January 2019 Updated 1/23/19 9:12AM

Local Board Hearing Information January 2019 Updated 1/23/19 9:12AM Adams hearing #1 Adams County Service Complex, Conference room, Room 125 - Decatur 01/22/2019 9:00 am EL CARRETON, INC RR0132240 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: EL CARRETON 922 W 500 SOUTH Berne IN 46711 MONROE PACKAGE LIQUORS,INC DL0114209 Beer Wine & Liquor - Package Store Renewal DBA: MONROE PACKAGE LIQUOR 119 JACKSON ST Monroe IN 46772 Allen hearing #1 Citizens Square 200 E. Berry, Garden Level, Community Rm.030 - Fort Wayne 01/14/2019 9:30 am BILLY'S DUGOUT, LLC RR0202584 Beer & Wine Retailer - Restaurant Renewal DBA: BILLY'S DUGOUT 3401 FAIRFIELD AVE. Fort Wayne IN 46807 D&BD INVESTMENTS LLC RR0231495 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: RABBIT'S GENTLEMENS CLUB 1407 SOUTH CALHOUN STREET Fort Wayne IN 46802 DPB INC. RR0235030 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (209) Renewal DBA: SALVATORI'S 10337 ILLINOIS RD Fort Wayne IN 46814 FORT WAYNE INVESTMENT CLUB LLC RR0234026 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: NEXT LEVEL BAR AND ARCADE 1706 W TILL ROAD Fort Wayne IN 46818 HONG KIM CORPORATION RR0233306 Beer & Wine Retailer - Restaurant Renewal DBA: SAIGON RESTAURANT 2006 S CALHOUN ST Fort Wayne IN 46802 HUNGRY HILL ENTERPRISES LLC RR0235008 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) New Application DBA: THE GREEN FROG INN 820 SPRING ST Fort Wayne IN 46808 KYB HOLDINGS, LLC RR0234347 Beer Wine & Liquor - Restaurant (210) Renewal DBA: HIDEOUT 125 10350 COLDWATER RD Fort Wayne IN 46825 LAKES VENTURE LLC DL0230307 Beer & Wine Dealer - Grocery Store Renewal DBA: FRESH THYME FARMERS MARKET 4320 COLDWATER RD Fort Wayne IN 46805 Las Lomas Mexican Grill, Inc. -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

View Accessible

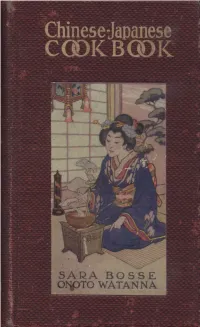

SARA BOSSE ONOTO WATANNA BEATRICE V. GRANT MSU 1929 - 1965 PROFESSOR of FOODS & NUTRITION COLLECTOR of RARE COOKERY BOOKS Her private collection of rare cookery books was donated by her sister, Dr. Rhoda Grant, to the M SU Libraries, May 1984. Jan Longone Wine & Food Books 1207 W. Madison Ann Arbor, Ml 48103 734-663-4894 CHINESE-JAPANESE COOK-BOOK CHINESE JAPANESE COOK BOOK BY SARA BOSSE AND ONOTO WATANNA RAND McNALLY & COMPANY CHICAGO NEW YORK Copyright, 1914, by R a n d , M c N a l l y & C o m p a n y T h e R and-M c N ally P r ess C hicago CONTENTS Preface............................................................... i PART I CHINESE RECIPES PAGE Rules for Cooking.......................................... 9 Soups................................................................. 12 G ravy................................................................ 19 Fish.................................................................... 20 Poultry and Game......................................... 27 M eats................................................................ 36 Chop Sueys...................................................... 41 Chow Mains.................................................... 47 Fried Rice........................................................ 51 Omelettes......................................................... 54 Vegetables........................................................ 57 Cakes................................................................. 64 PART II JAPANESE RECIPES Soups................................................................ -

The Southern Cook Book of Fine Old Recipes

"APPETITE - WHETTING, COMPETENT, DELICIOUS RECIPES THAT HAVE MADE SOUTHERN COOKING FAMOUS THE WORLD c OVER." Charlotte, N. C., News. From the collection of the o Prelinger i a JJibrary San Francisco, California 2006 THE SOUTHERN COOK BOOK OF FINE OLD RECIPES Compiled and Edited by Lillie S. Lnstig S. Claire Sondheii Sarah Rensel Decorations by H. Charles Kellui Copyrighted 1935 CULINARY ARTS PRESS P. O. Box 915, Reading, Pa. INDEX Page Page APPETIZERS CANDIES Avocado Canapes 47 Candied Orange or Grapefruit Peel 46 Cheese Appetizer for the Master's Caramels, Grandmother's 46 Cocktail 47 Cocoanut Pralines, Florida 46 Delicious Appetizer 47 Fudge, Aunt Sarah's 46 Papaya Canape 26 Goober Brittle 46 Papaya Cocktail 26 Pecan Fondant 46 Pigs in Blankets 47 Pralines, New Orleans 46 . Shrimp Avocado Cocktail 47 Shrimp Paste 18 EGGS BEVERAGES Creole Omelet 29 Eggs Biltmore Goldenrod 29 Egg Nog 48 Eggs, New Orleans 29 Idle Hour Cocktail 48 Eggs, Ponce de Leon 29 Mint Julep 48 Eggs Stuffed with Chicken Livers 29 Mint Tea 21 Orange Julep 48 FRITTERS, PANCAKES, WAFFLES Planter's Punch 48 and MUSH Spiced Cider 48 Apple Fritters 28 Syllabub, North Carolina 48 Apricot Fritters 28 Tom and Jerry, Southern Style 48 Corn Bread Fritters 28 Zazarac Cocktail . ... 48 Corn Fritters 28 Corn Meal Dodgers for Pot Likker 6 BREAD AND BISCUITS Corn Meal Mush 35 Flannel Cakes 32 Batter Bread, Mulatto Style Flapjacks, Georgia 32 Baking Powder Biscuits, Mammy's Fruit Fritter Batter 28 Beaten Biscuits Griddle Cakes 32 Buttermilk Muffins Griddle Cakes, Sour Milk 32 Cheese Biscuits Hoe Cake : 30 Miss Southern .. -

Food Fair Recipe Book2020.Pdf

Schedule Baby-n-Me Fair August 2020 (909)-864-1097 ext 4764 W.E.L.L. Classes at all sites 3:00pm Registration/Vendors 16 week sessions learning ways to 3:50pm-4:20pm Welcome-Mark Jensen feel better, have energy, and lose the Bird Singers/Blessing weight WITHOUT dieting. Native Plant Educator Interview with (909) 864-1097 ext 4764 Aaron Saubel by Afua Khumalo World Breastfeeding Event August 2020 4:20pm-4:45pm Healing Garden-Valerie Dobesh Cooking Food Demos monthly 4:45pm-6pm Booths & Vendors Open (909) 864-1097 ext 4764 Wholesome Nations Eats Guide-www.rsbcihi.org (Resources Tab) 4:45pm-5:15pm Terry Goedel-Native American Hoop Dancing Monthly Healthy Options Classes at San Manuel 5:30pm-5:45pm Adult Tai Chi-Daniel Mazza (951) 849-4761 ext 4722 Monthly Healthy Options Classes at Soboba 4:45pm-5:45pm Kid’s Fun Zone-Shellbi Gallemore (951)849-4761 ext 4722 Diabetes Team 6:00pm Booths/Vendors/Raffles/Closing Mini Olympics May 2, 2020 Soboba Reservation-Sports Complex (951)-849-4761 ext 4781 *Booths will open at 4:45pm. No booths or vendors will be open from 3:50pm-4:45pm* Fitness Reward Program (951)849-4761 ext 1151 San Manuel, Barstow, Pechanga Fitness Classes Presented by: (951)849-4761 ext 4721 Soboba, Morongo, Torres Martinez, Anza Fitness Classes Diabetes Team (951)849-4761 ext 1155 Schedule Baby-n-Me Fair August 2020 (909)-864-1097 ext 4764 W.E.L.L. Classes at all sites 3:00pm Registration/Vendors 16 week sessions learning ways to 3:50pm-4:20pm Welcome-Mark Jensen feel better, have energy, and lose the Bird Singers/Blessing weight WITHOUT dieting. -

Indian Family Meal Ideas

100+ INDIAN FAMILY MEAL IDEAS Includes- Meal planning tips Indian meal options My family meal options printable Indian grocery list printable Weekly meal plan printable Weekly food diary printable B E I N G R U B I T A H . C O M There's nothing like a delicious home-cooked meal. Even better if it comes pre-planned because that's what we all stress about the most, isn't it? What should I cook? What different can I make? How can I make sure we're eating right? If only you had an easy way of getting these questions answered. No more stress buddy! Presenting you an approach that not only fills stomachs but gives you a chance at being more mindful about what you cook and eat as a family. In fact you maybe already doing this in your head but are just not able to put it together or as in my case become forgetful. This approach has helped me immensely in ensuring that I get the peace of mind I deserve over meal times, especially with a hectic routine. I'm sure it will help you too. Rubitah 1.Read through the meal ideas listed in pages 4-8. Mark them in different ways. You can choose your own categories. Mine usually go like these- family favourites want to try easy peasy nutritious musts to double and freeze Now take a print out of the "My family meal options" (refer page 9) and write down the meal options in the categories of your choice. -

Cookin' Cajun.Pdf

THE COOKIN' CAJUN by E-Cookbooks.net -: Acadian Peppered Shrimp -: Andouille a la Jeannine -: Andouille in Comforting Barbecue Sauce -: Andouille Smoked Sausage in Red Gravy -: Baked Oysters -: Baked Vegetable Gumbo Creole -: Barbecue Sauce -: Barbecued Pot Roast -: Barbecued Shrimp -: Basic Cooked Rice -: Bayou Baked Red Snapper -: Bayou Boeuf Jambalaya -: Bayou Shrimp Creole -: Beef Ribeye Stuffed with Pecans -: Blackened Arctic Char -: Blackened Red Steaks -: Blackened Redfish -: Boiled Crabs -: Boiled Crawfish -: Boiled Crawfish with Vegetables -: Brennan's Shrimp Creole -: Broiled Alligator Tail with Lemon Butter Sauce -: Cajun Catfish -: Cajun Catfish a la Don -: Cajun Catfish Remoulade -: Cajun Chicken Salad -: Cajun Creole -: Cajun Meat Loaf -: Cajun Pork Burgers -: Cajun Prime Rib -: Cajun Shrimp -: Cajun Snapper -: Cajun-Style Andouille -: Cajunized Oriental Pork Chops -: Chicken and Sausage Gumbo -: Chicken Okra Gumbo with Sausage -: Chicken Sausage Oyster Gumbo -: Chicken-Okra Gumbo Plains-Style -: Chili [ Cajun Style ] -: Classic Chicken Gumbo -: Country Rice -: Crawfish Jambalaya -: Crayfish Etouffee -: Cream of Onion Soup -: Creole Baked Fish -: Creole Candied Yams -: Creole Chicken Soup -: Creole Gumbo Pot -: Creole Liver & Rice -: Creole Seafood Gumbo -: Creole-Style Red Beans & Rice -: Dirty Rice -: Dry Roux -: Easy Lamb Creole Gumbo -: File' Gumbo Lafayette -: Grilled Catfish Cajun Style -: Gumbo Ya Ya -: Ham & Corn Chowder -: Ham Skillet Gumbo -: Hoppin John Soup -: Hot and Spicy Shrimp -: Jambalaya Salad -: John's -

85 3. Modern Development of the Cm Vowels

Mongolic phonology and the Qinghai-Gansu languages Nugteren, H. Citation Nugteren, H. (2011, December 7). Mongolic phonology and the Qinghai-Gansu languages. LOT dissertation series. Utrecht : LOT, Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18188 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/18188 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 3. MODERN DEVELOPMENT OF THE CM VOWELS 3.1. Introduction In the following pages the main developments of each CM vowel will be discussed. Each section will start with the „default‟ development, which need not be the most frequent development. The quality of unaccented vowels is rather unstable in the QG languages, and easily influenced by the consonant environment. After the default reflexes the most common conditioned changes will be discussed. Whenever poss- ible the focus will be on correspondences of historical and comparative importance. In all modern languages the CM vowels underwent several changes, which are correlated to changes in the vowel system of each language as a whole. Such changes often affect the number of vowel phonemes, and modify or undermine vowel harmony. On the level of the lexeme such changes affect both the quantity and quality of the vowels. In all three peripheries we find that the original vocalism is simplified. In general the distinction between *ï and *i is (all but) absent, and the number of phonemic rounded vowel qualities was reduced. The Dagur system and the Shirongol system are the result of different routes of simplification.