The Rhythm of Space and the Sound of Time Michael Chekhov's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 10 | Issue 2 July 2020 Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling Ceire Monahan Montclair State University Mika Munakata Montclair State University Ashwin Vaidya Montclair State University Sean Gandini Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Monahan, C. Munakata, M. Vaidya, A. and Gandini, S. "Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 10 Issue 2 (July 2020), pages 291-314. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.202002.14 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol10/iss2/14 ©2020 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling Ceire Monahan Department of Mathematical Sciences, Montclair State University, New Jersey, USA -

Happy Birthday!

THE THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Quote of the Day “That’s what I love about dance. It makes you happy, fully happy.” Although quite popular since the ~ Debbie Reynolds 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country (no kidding). Happy Birthday! 1998 – Burger King published a full-page advertisement in USA Debbie Reynolds (1932–2016) was Today introducing the “Left-Handed a mega-talented American actress, Whopper.” All the condiments singer, and dancer. The acclaimed were rotated 180 degrees for the entertainer was first noticed at a benefit of left-handed customers. beauty pageant in 1948. Reynolds Thousands of customers requested was soon making movies and the burger. earned a nomination for a Golden Globe Award for Most Promising 2005 – A zoo in Tokyo announced Newcomer. She became a major force that it had discovered a remarkable in Hollywood musicals, including new species: a giant penguin called Singin’ In the Rain, Bundle of Joy, the Tonosama (Lord) penguin. With and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. much fanfare, the bird was revealed In 1969, The Debbie Reynolds Show to the public. As the cameras rolled, debuted on TV. The the other penguins lifted their beaks iconic star continued and gazed up at the purported Lord, to perform in film, but then walked away disinterested theater, and TV well when he took off his penguin mask into her 80s. Her and revealed himself to be the daughter was actress zoo director. Carrie Fisher. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) HURSDAY PRIL T , A 1, 2021 Today is April Fools’ Day, also known as April fish day in some parts of Europe. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles ADissertationsubmittedinpartialsatisfactionofthe requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics by Jay Cummings Committee in charge: Professor Ron Graham, Chair Professor Jacques Verstra¨ete, Co-Chair Professor Fan Chung Professor Shachar Lovett Professor Je↵Remmel Professor Alexander Vardy 2016 Copyright Jay Cummings, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jay Cummings is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on micro- film and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To mom and dad. iv EPIGRAPH We’ve taught you that the Earth is round, That red and white make pink. But something else, that matters more – We’ve taught you how to think. — Dr. Seuss v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Epigraph ...................................... v TableofContents.................................. vi ListofFigures ................................... viii List of Tables . ix Acknowledgements ................................. x AbstractoftheDissertation . xii Chapter1 JugglingCards ........................... 1 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.1.1 Jugglingcardsequences . 3 1.2 Throwingoneballatatime . 6 1.2.1 The unrestricted case . 7 1.2.2 Throwingeachballatleastonce . 9 1.3 Throwing m 2ballsatatime. 16 1.3.1 A digraph≥ approach . 17 1.3.2 Adi↵erentialequationsapproach . 21 1.4 Throwing di↵erent numbers of balls at di↵erent times . 23 1.4.1 Boson normal ordering . 24 1.5 Preserving ordering while throwing . 27 1.6 Juggling card sequences with minimal crossings . 32 1.6.1 A reduction bijection with Dyck Paths . 36 1.6.2 A parenthesization bijection with Dyck Paths . 48 1.6.3 Non-crossingpartitions . 52 1.6.4 Counting using generating functions . -

The Michael Chekhov Technique: in the Classroom and on Stage

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 The Michael Chekhov Technique: In The Classroom and On Stage Josh Chenard Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/71 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction We are trying to find the technique for those gifted actors who want to consciously develop their talents, who want to master their abilities and not flounder aimlessly, relying upon vague inspiration…(a technique which) will teach you to economize on time in preparing your part, but without succumbing to haste and deadening cliches. -Michael Chekhov David Mamet, in his book True and False, argues against the need for acting technique, especially those created by or derived from Constantin Stanislavski. “The organic demands made on the actors,” he states, “are much more compelling…than anything prescribed or forseen by this or any other ‘method’ of acting. (Mamet 6)” Stella Adler, arguably one of the most important acting teachers of the 20th Century, agreeing with Mamet, stating “The classroom is not ideal…I learned acting by acting.(Adler 11)” These sentiments are echoed and argued in academia as well as in the professional theater world begging the questions: do actors require a technique? Is it necessary? Is it important? My answer to these questions is an immediate and unabashed YES. -

2009–2010 Season Sponsors

2009–2010 Season Sponsors The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2009–2010 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Audrey and Rick Rodriguez Yvonne Cattell Renee Fallaha $50,001-$100,000 Marilynn and Art Segal Rodolfo Chacon Heather M. Ferber José Iturbi Foundation Kirsten and Craig M. Springer, Joann and George Chambers Steven Fischer Ph.D. Rodolfo Chavez The Fish Company Masaye Stafford Patron Liming Chen Elizabeth and Terry Fiskin Charles Wong $20,001-$50,000 Wanda Chen Louise Fleming and Tak Fujisaki Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Margie and Ned Cherry Jesus Fojo The Capital Group Companies Friend Drs. Frances and Philip Chinn Anne Forman Charitable Foundation $1-$1,000 Patricia Christie Dr. Susan Fox and Frank Frimodig Richard Christy National Endowment for the Arts Maureen Ahler Sharon Frank Crista Qi and Vincent Chung Eleanor and David St. -

Analysis and Visualization of Collective Motion in Football Analysis of Youth Football Using GPS and Visualization of Professional Football

UPTEC F 15068 Examensarbete 30 hp December 2015 Analysis and visualization of collective motion in football Analysis of youth football using GPS and visualization of professional football Emil Rosén Abstract Analysis and visualization of collective motion in football Emil Rosén Teknisk- naturvetenskaplig fakultet UTH-enheten Football is one of the biggest sports in the world. Professional teams track their player's positions using GPS (Global Positioning System). This report is divided into Besöksadress: two parts, both focusing on applying collective motion to football. Ångströmlaboratoriet Lägerhyddsvägen 1 Hus 4, Plan 0 The goal of the first part was to both see if a set of cheaper GPS units could be used to analyze the collective motion of a youth football team. 15 football players did two Postadress: experiments and played three versus three football matches against each other while Box 536 751 21 Uppsala wearing a GPS. The first experiment measured the player's ability to control the ball while the second experiment measured how well they were able to move together as Telefon: a team. Different measurements were measured from the match and Spearman 018 – 471 30 03 correlations were calculated between measurements from the experiments and Telefax: matches. Players which had good ball control also scored more goals in the match and 018 – 471 30 00 received more passes. However, they also took the middle position in the field which naturally is a position which receives more passes. Players which were correlated Hemsida: during the team experiment were also correlated with team-members in the match. http://www.teknat.uu.se/student But, this correlation was weak and the experiment should be done again with more players. -

THE PATH of the ACTOR 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 13111 Michael Chekhov, Nephew of Anton Chekhov, Was Arguably One of the Greatest 4 Actors of the Twentieth Century

1111 2 3 4 51 THE PATH OF THE ACTOR 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 13111 Michael Chekhov, nephew of Anton Chekhov, was arguably one of the greatest 4 actors of the twentieth century. From his time as Stanislavsky’s pupil, followed 5 by his artistic leadership in the Second Moscow Art Academic Theatre, his 6 enforced emigration from the Soviet Union and long pilgrimage around 7 Europe, to his work in Hollywood, his life has made a huge impact on the 8 acting profession. Chekhov’s remarkable actor-training techniques inspired many Hollywood 9 legends – including Anthony Hopkins and Jack Nicholson – and his tech- 20111 niques remain one of the theatre’s best kept secrets. 1 This first English translation of Chekhov’s autobiographies combines The 2 Path of the Actor, from 1928, and extensive extracts from his later Life and 3 Encounters. Full of humorous and insightful observations involving promi- 4 nent characters from Moscow and the European theatre of the early twentieth 5111 century, Chekhov takes us through events in his acting career and personal 6 life, from his childhood in St Petersburg until his emigration from Latvia and 7 Lithuania in the early 1930s. 8 Chekhov’s witty, penetrating (and at times immensely touching) accounts 9 have been edited by Andrei Kirillov, whose extensive and authoritative notes 30111 accompany the autobiographies. Co-editor, Anglo-Russian trained actor, Bella 1 Merlin, also provides a useful hands-on overview of how the contemporary practitioner might use and develop Chekhov’s ideas. 2 The Path of the Actor is an extraordinary document that allows us unprece- 3 dented access into the life, times, mind and soul of a remarkable man and a 4 brilliant artist. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability. -

The Routledge Companion to Michael Chekhov. Edited by Marie- Christine Autant Mathieu and Yana Meerzon

BOOK REVIEWS The Routledge Companion to Michael Chekhov. Edited by Marie- Christine Autant Mathieu and Yana Meerzon. New York: Routledge, 2015. 434 pp. Reviewed by Conrad Alexandrowicz As I write this, I’m in the middle of rehearsals for Giraudoux’s The Madwoman of Chaillot at the University of Victoria’s Department of Theatre, in which I’m employing various key tools developed by Michael Chekhov over the course of his career as an actor, director, and visionary pedagogue. They include the Imaginary Body, Archetypal and Psychological Gestures, Atmospheres, and Qualities of Movement. It has been fascinating to read this wide-ranging and very thorough collection of essays by a host of renowned Chekhov scholars and practitioners in Europe, the UK, and the US while engaged in the process of introducing a cast of twenty young actors to what is for them an entirely new set of ideas and practices about acting and the theatre. My own exposure to Chekhov’s methods occurred in the summer of 2014 when I participated in the National Michael Chekhov Association’s (NMCA) annual Summer Training Intensive, held at the University of Southern Maine. Instructors and actors Lisa Dalton and Wil Kilroy, passionate, devoted and articulate adherents of Chekhov’s work, were mentored by the late Mala Powers, whose name appears frequently in this book; while working as an actor in Hollywood, she was taught and coached by the Russian master. I was struck by many things about the work: that it proceeds from the assumption that an actor is an artist, not merely a puppet; by its balance of methods that reveal meaning in both text and the body; and by its use of specific, sensible, and accessible tools in the creation of characters. -

Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training Richard Solomon

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 5-2002 Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training Richard Solomon Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Solomon, Richard, "Michael Chekhov and His Approach to Acting in Contemporary Performance Training" (2002). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 615. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/615 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. MICHAEL CHEKHOV AND HIS APPROACH TO ACTING IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE TRAINING by Richard Solomon B.A. University of Southern Maine, 1983 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Theatre) The Graduate School The University of Maine May, 2002 Advisory Committee: Tom Mikotowicz, Associate Professor of Theatre, Advisor Jane Snider, Associate Professor of Theatre Sandra Hardy, Associate Professor of Theatre MICaAEL CHEKHOV AND HIS APPROACH TO ACTING IN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE TRAINING By Richard Solomon Thesis ~dhsor:Dr. Tom Mikotowicz An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in Theatre) May, 2002 Michael Chekhov was an actor, diuector, and teacher who was determined to develop a clear and accessible acting approach. During his lifetime, his ideas were often viewed as too radical and mystical. Over the past decade however, the Chekhov method of actor training has enjoyed an expansion of interest. -

|||GET||| Konstantin Stanislavsky 1St Edition

KONSTANTIN STANISLAVSKY 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Franc Chamberlain | 9780415258869 | | | | | Konstantin Stanislavski Benedetti argues that the course at the Opera-Dramatic Studio is "Stanislavski's true testament". This is a private listing and your identity will not be disclosed to anyone except the seller. Moscow: Iskusstvo, Writing inside. Counsell, Colin. Actors, managers, all sorts of celebrities join in a chorus of the most extravagant praise. Drawing on Gogol's notes on the play, Stanislavski insisted that its exaggerated external action must be justified through the creation of a correspondingly intense inner life; see Benedetti a, — and— Lev Pospekhin was from the Bolshoi Ballet. Add to Basket New Hardcover Condition: new. That is why the physical line of a role is easier to create than the psychological. What Stanislavski told Stella Adler was exactly what he had been telling his actors at home, what indeed he had advocated in his notes for Leonidov in the production plan for Othello. Fighting against the artificial and highly stylized theatrical conventions of the late 19th century, Stanislavsky sought instead the reproduction of authentic emotions at every performance. Konstantin Stanislavsky 1st edition tostado. Most significantly, it impressed a promising writer and director, Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko —whose later association with Stanislavsky was to have a paramount influence on the theatre. In contrast, Stanislavski recommended to Stella Adler an indirect pathway to emotional expression via physical action. Add to Basket Used Condition: good. More information about this seller Contact this seller 1. Pages: Language: Russian. Petersburg in had been a failure. Se envian desde diferentes localizaciones por DHL. -

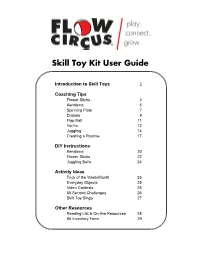

Skill Toy Kit User Guide

Skill Toy Kit User Guide Introduction to Skill Toys 2 Coaching Tips Flower Sticks 3 Kendama 5 Spinning Plate 7 Diabolo 9 Flop Ball 11 Yo-Yo 12 Juggling 14 Creating a Routine 17 DIY Instructions Kendama 20 Flower Sticks 22 Juggling Balls 24 Activity Ideas Trick of the Week/Month 25 Everyday Objects 25 Video Contests 25 60 Second Challenges 26 Skill Toy Bingo 27 Other Resources Reading List & On-line Resources 28 Kit Inventory Form 29 Introduction to Skill Toys You and your team are about to embark on a fun adventure into the world of skill toys. Each toy included in this kit has its own story, design, and body of tricks. Most of them have a lower barrier to entry than juggling, and the following lessons of good posture, mindfulness, problem solving, and goal setting apply to all. Before getting started with any of the skill toys, it is important to remember to relax. Stand with legs shoulder width apart, bend your knees, and take deep breaths. Many of them require you to absorb energy. We have found that the more stressed a player is, the more likely he/she will be to struggle. Not surprisingly, adults tend to have this problem more than kids. If you have players getting frustrated, remind them to relax. Playing should be fun! Also, remind yourself and other players that even the drops or mess-ups can give us valuable information. If they observe what is happening when they attempt to use the skill toys, they can use this information to problem solve.