The Geography of Gandhāran Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking at Gandhāra

HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, nr 4 (2015) ISSN 2299-2464 Kumar ABHIJEET (Magadh University, India) Looking at Gandhāra Keywords: Art History, Silk Route, Gandhāra It is not the object of the story to convey a happening per se, which is the purpose of information; rather, it embeds it in the life of the storyteller in order to pass it on as experience to those listening. It thus bears the marks of the storyteller much as the earthen vessel bears the marks of the potter's hand. —Walter Benjamin, "On Some Motifs in Baudelaire" Discovery of Ancient Gandhāra The beginning of the 19th century was revolutionary in terms of western world scholars who were eager to trace the conquest of Alexander in Asia, in speculation of the route to India he took which eventually led to the discovery of ancient Gandhāra region (today, the geographical sphere lies between North West Pakistan and Eastern Afghanistan). In 1808 CE, Mountstuart Elphinstone was the first British envoy sent in Kabul when the British went to win allies against Napoleon. He believed to identify those places, hills and vineyard described by the itinerant Greeks or the Greek Sources on Alexander's campaign in India or in their memory of which the Macedonian Commanders were connected. It is significant to note that the first time in modern scholarship the word “Thupa (Pali word for stupa)” was used by him.1 This site was related to the place where Alexander’s horse died and a city called Bucephala (Greek. Βουκεφάλα ) was erected by Alexander the Great in honor of his black horse with a peculiar shaped white mark on its forehead. -

Buddhist Histories

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 25 Number 1-2 2002 Buddhist Histories Richard SALOMON and Gregory SCHOPEN On an Alleged Reference to Amitabha in a KharoÒ†hi Inscription on a Gandharian Relief .................................................................... 3 Jinhua CHEN Sarira and Scepter. Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics 33 Justin T. MCDANIEL Transformative History. Nihon Ryoiki and Jinakalamalipakara∞am 151 Joseph WALSER Nagarjuna and the Ratnavali. New Ways to Date an Old Philosopher................................................................................ 209 Cristina A. SCHERRER-SCHAUB Enacting Words. A Diplomatic Analysis of the Imperial Decrees (bkas bcad) and their Application in the sGra sbyor bam po gnis pa Tradition....................................................................................... 263 Notes on the Contributors................................................................. 341 ON AN ALLEGED REFERENCE TO AMITABHA IN A KHARO∑™HI INSCRIPTION ON A GANDHARAN RELIEF RICHARD SALOMON AND GREGORY SCHOPEN 1. Background: Previous study and publication of the inscription This article concerns an inscription in KharoÒ†hi script and Gandhari language on the pedestal of a Gandharan relief sculpture which has been interpreted as referring to Amitabha and Avalokitesvara, and thus as hav- ing an important bearing on the issue of the origins of the Mahayana. The sculpture in question (fig. 1) has had a rather complicated history. According to Brough (1982: 65), it was first seen in Taxila in August 1961 by Professor Charles Kieffer, from whom Brough obtained the photograph on which his edition of the inscription was based. Brough reported that “[o]n his [Kieffer’s] return to Taxila a month later, the sculpture had dis- appeared, and no information about its whereabouts was forthcoming.” Later on, however, it resurfaced as part of the collection of Dr. -

The Apsidal Temple of Taxila

T HE THE APSIDAL TEMPLE OF TAXILA: A TRADITIONAL HYPOTHESIS AND PSIDA L POSSIBLE NEW INTERPRETATIONS T EMP L E Luca Colliva O F T AXI L A The so called ‘apsidal temple’ of Sirkap is an imposing building belonging, according to Marshall, : T RADI to the Indo-Parthian period (Figure 1) (Marshall 1951, 150-151). It is built over an artificial terrace T facing the main street in the northern part of the town and was brought to light by John Marshall at IONA th the beginning of the last century after some minor excavations during the 19 century. Unlike his L H predecessors, who were very doubtful about its nature (Cunningham 1871, 126-128), Marshall identified YPO T this building as a Buddhist gr. ha-stūpa (Marshall 1930, 111; Marshall 1951, 150); this interpretation HESIS has indeed never been questioned and is accepted, also, in the last study on urban form in Taxila A (Coningham & Edwards 1998, 50). ND However, we cannot deem this attribution certain. No traces are detectable of the main stūpa P OSSIB Marshall recognises in the ‘circular room’ (Marshall 1951, 151). Besides, what Marshall describes as L E two additional stūpas are nothing but scanty remains of foundations belonging to two monuments N of uncertain nature. As I already pointed out in a more exhaustive way (Colliva in press), Marshall EW I was probably convinced that the apsidal shape of this building was enough to identify it as a N T Buddhist caitya. The discovery at Sonkh of an apsidal-shaped temple, probably dedicated to a nāga ERPRE cult, shows, on the contrary, that non-Buddhist religious buildings with an apsidal plan occur in T A T periods chronologically consistent with that of the “apsidal temple” of Sirkap (Härtel 1970; Härtel IONS 1993). -

Genetic Analysis of the Major Tribes of Buner and Swabi Areas Through Dental Morphology and Dna Analysis

GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS MUHAMMAD TARIQ DEPARTMENT OF GENETICS HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA 2017 I HAZARA UNIVERSITY MANSEHRA Department of Genetics GENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE MAJOR TRIBES OF BUNER AND SWABI AREAS THROUGH DENTAL MORPHOLOGY AND DNA ANALYSIS By Muhammad Tariq This research study has been conducted and reported as partial fulfillment of the requirements of PhD degree in Genetics awarded by Hazara University Mansehra, Pakistan Mansehra The Friday 17, February 2017 I ABSTRACT This dissertation is part of the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan (HEC) funded project, “Enthnogenetic elaboration of KP through Dental Morphology and DNA analysis”. This study focused on five major ethnic groups (Gujars, Jadoons, Syeds, Tanolis, and Yousafzais) of Buner and Swabi Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan, through investigations of variations in morphological traits of the permanent tooth crown, and by molecular anthropology based on mitochondrial and Y-chromosome DNA analyses. The frequencies of seven dental traits, of the Arizona State University Dental Anthropology System (ASUDAS) were scored as 17 tooth- trait combinations for each sample, encompassing a total sample size of 688 individuals. These data were compared to data collected in an identical fashion among samples of prehistoric inhabitants of the Indus Valley, southern Central Asia, and west-central peninsular India, as well as to samples of living members of ethnic groups from Abbottabad, Chitral, Haripur, and Mansehra Districts, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and to samples of living members of ethnic groups residing in Gilgit-Baltistan. Similarities in dental trait frequencies were assessed with C.A.B. -

Cultural Heritage Vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond

Cultural Heritage vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond Cheryl Benard Eli Sugarman Holly Rehm CONFERENCE REPORT December 2012 Cultural Heritage vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond June 4-5, 2012 SAIS, Johns Hopkins University Washington, D.C. 20036 sponsored by Ludus and ARCH Virginia Conference Report Cheryl Benard Eli Sugarman Holly Rehm © Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program – A Joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center Johns Hopkins University-SAIS, 1619 Massachusetts Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20036 Institute for Security and Development Policy, V. Finnbodav. 2, Stockholm-Nacka 13130, Sweden www.silkroadstudies.org “Cultural Heritage vs. Mining on the New Silk Road? Finding Technical Solutions for Mes Aynak and Beyond” is a Conference Report published by the Central Asia- Caucasus Institute and the Silk Road Studies Program. The Silk Road Papers Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Joint Center, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Joint Center is a transatlantic independent and non-profit research and policy center. It has offices in Washington and Stockholm and is affiliated with the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins University and the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and Development Policy. It is the first institution of its kind in Europe and North America, and is firmly established as a leading research and policy center, serving a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. The Joint Center is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development in the region. -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

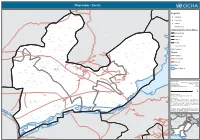

Overview - Swabi

Overview - Swabi Tor Ghar Legend Takhto Sar ! Shamma Khui ! Shama Shapla !^! ! National ! Khanpur ! ! Shahole !! Natian ! Khanpur Ajarh Province Post Gadai ! Natian ! Rizzar !!! District ! Mir Dandikot Sherdarra ! Shahe ! Sherdarah ! Settlements Mir Shahai Dandai ! Tor Gat ! Naranji Administartive Boundaries Mardan ! Badrai Chatara ! Buner ! Kund International Miralai ! Mehr Kamar Burai ! ! Bako ! Ali Dhand Bural ! Birgalai Mir Dai ! ! Pirgalai Khisha Khesha ! Naogram ! Provincial Kaniza Dheri ! ! Lakha Tibba Dheri Lakha Madda Khel Jabba ! Tiga Dheri Ghulama ! Mazghund ! Sikandarabad ! Muz Ghunar ! Jabba District Parmulai Bagga ! Jabba Purmali ! Ganikot ! ! Ganrikot Kodi Dherai Kodi Dheri ! Utla Bahai Baho Leran ! ! Satketar ! Palosai ! Gabai Amankot ! Salketai Ghabasanai ! Tehsil Bar Amrai Gabasanrai ! ! ! Gumbati Dheri Gumbat Dherai Amral Bala Bar Amral Bala ! Gunj Gago ! Dheri ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sangbalai ! Dherai ! Gani Chhatra Bar Dewalgari ! ! Line of control ! Punrawal Shewa ! Gangodher ! Aziz Dheri Banda ! Shingrai ! ! ! Katar Dheri ! Seri ! Kuz Amrai ! Achelai Rasoli Dheri Inian Dheri ! Gangu Dheri Shingrai Kuz Dewalgari ! ! Khalil ! ! ! Gangudhei Seri Injan Asota Sharif Asota Gangudher Makia ! ! Coastline Dheri Nuro Banda Chini Rafiqueabad ! Dheri ! Nakla Jogia ! Takhtaband Dheri Dagi ! Banda ! ! Spin ! Girro Sherghund Kani Aro Bore Badga ! Banda ! Katgram ! ! Sheikhjana ! Shaikh Jana Dakara Banda Roads ! Sukaili ! ! Ismaila Tali ! Adina ! ! ! Nawe Kili Pal Qadra ! Mangal Dheri Sandwa ! Chai ! Kalu Khan ! Shewa Chowk Aio Kolagar -

Status and Red List of Pakistan's Mammals

SSttaattuuss aanndd RReedd LLiisstt ooff PPaakkiissttaann’’ss MMaammmmaallss based on the Pakistan Mammal Conservation Assessment & Management Plan Workshop 18-22 August 2003 Authors, Participants of the C.A.M.P. Workshop Edited and Compiled by, Kashif M. Sheikh PhD and Sanjay Molur 1 Published by: IUCN- Pakistan Copyright: © IUCN Pakistan’s Biodiversity Programme This publication can be reproduced for educational and non-commercial purposes without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior permission (in writing) of the copyright holder. Citation: Sheikh, K. M. & Molur, S. 2004. (Eds.) Status and Red List of Pakistan’s Mammals. Based on the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan. 312pp. IUCN Pakistan Photo Credits: Z.B. Mirza, Kashif M. Sheikh, Arnab Roy, IUCN-MACP, WWF-Pakistan and www.wildlife.com Illustrations: Arnab Roy Official Correspondence Address: Biodiversity Programme IUCN- The World Conservation Union Pakistan 38, Street 86, G-6⁄3, Islamabad Pakistan Tel: 0092-51-2270686 Fax: 0092-51-2270688 Email: [email protected] URL: www.biodiversity.iucnp.org or http://202.38.53.58/biodiversity/redlist/mammals/index.htm 2 Status and Red List of Pakistan Mammals CONTENTS Contributors 05 Host, Organizers, Collaborators and Sponsors 06 List of Pakistan Mammals CAMP Participants 07 List of Contributors (with inputs on Biological Information Sheets only) 09 Participating Institutions -

Afghan Opiate Trade 2009.Indb

ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna ADDICTION, CRIME AND INSURGENCY The transnational threat of Afghan opium Copyright © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), October 2009 Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), in the framework of the UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme/Afghan Opiate Trade sub-Programme, and with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC field offices for East Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, Pakistan, the Russian Federation, Southern Africa, South Asia and South Eastern Europe also provided feedback and support. A number of UNODC colleagues gave valuable inputs and comments, including, in particular, Thomas Pietschmann (Statistics and Surveys Section) who reviewed all the opiate statistics and flow estimates presented in this report. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team, including, in particular, the Anti Narcotics Force of Pakistan, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan and the World Customs Organization. Thanks also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and of the United Nations Department of Safety and Security, Afghanistan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Lead researcher, Afghan -

Phase Iii Architecture and Sculpture from Taxila 6.1

CHAPTER SIX PHASE III ARCHITECTURE AND SCULPTURE FROM TAXILA 6.1 Introduction to the Phase III Developments in the Sacred Areas and Afonasteries ef Taxila and the Peshawar Basin A dramatic increase in patronage occurred across the Peshawar basin, Taxila, and Swat during phase III; most of the extant remains in these regions were constructed at this time. As devotional icons of Buddhas and bodhisattvas became increasingly popular, parallel trans formations occurred in the sacred areas, which still remained focused around relic stupas. In the Peshawar basin, Taxila, and to a lesser degree Swat, the widespread incorporation of large iconic images clearly reflects changes occurring in Buddhist practice. Although it is difficult to know how the sacred precincts were ritually used, modifications in the spatial organization of both sacred areas and monasteries provide some insight. Not surprisingly, the use and incorporation of devotional images developed regionally. The most dramatic shift toward icons is observed in the Peshawar basin and some of the Taxila sites. In contrast, Swat seemed to follow a different pattern, as fewer image shrines were fabricated and sacred areas were organized along different lines. This might reflect a lack of patronage; perhaps new sites following the Peshawar basin format were not commissioned because of a lack of resources. More likely, the Buddhist tradition in Swat was of a different character; some sites-notably Butkara I-show significant expansion following a uniquely Swati format. At a few sites in Swat, however, image shrines appear in positions analogous to those of the Peshawar basin; Nimogram and Saidu (figs. 109, 104) arc notable examples. -

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the