The Art Music's Road from a Closed System to Openness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test Free

FREE THE ELECTRIC KOOL-AID ACID TEST PDF Tom Wolfe | 416 pages | 10 Aug 2009 | St Martin's Press | 9780312427597 | English | New York, United States Merry Pranksters - Wikipedia In the summer and fall ofAmerica became aware of a growing movement of young people, based mainly out of California, called the "psychedelic movement. Kesey is a young, talented novelist who has just seen his first book, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nestpublished, and who is consequently on the receiving end of a great deal of fame and fortune. While living in Palo Alto and attending Stanford's creative writing program, Kesey signs up to participate in a drug study sponsored by the CIA. The drug they give him is a new experimental drug called LSD. Under the influence of LSD, Kesey begins to attract a band of followers. They are drawn to the transcendent states they can achieve while on the drug, but they are also drawn to Kesey, who is a charismatic leader. They call themselves the "Merry Pranksters" and begin to participate in wild experiments at Kesey's house in the woods of La Honda, California. These experiments, with lights and noise, are all engineered to create a wild psychedelic experience while on LSD. They paint everything in neon Day-Glo colors, and though the residents and authorities of La Honda are worried, there is little they can do, since LSD is not an illegal substance. The Pranksters first venture into the wider world by taking a trip east, to New York, for the publication of Kesey's newest novel. -

B2 Woodstock – the Greatest Music Event in History LIU030

B2 Woodstock – The Greatest Music Event in History LIU030 Choose the best option for each blank. The Woodstock Festival was a three-day pop and rock concert that turned out to be the most popular music (1) _________________ in history. It became a symbol of the hippie (2) _________________ of the 1960s. Four young men organized the festival. The (3) _________________ idea was to stage a concert that would (4) _________________ enough money to build a recording studio for young musicians at Woodstock, New York. Young visitors on their way to Woodstock At first many things went wrong. People didn't want Image: Ric Manning / CC BY (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0) any hippies and drug (5) _________________ coming to the original location. About 2 months before the concert a new (6) _________________ had to be found. Luckily, the organizers found a 600-acre large dairy farm in Bethel, New York, where the concert could (7) _________________ place. Because the venue had to be changed not everything was finished in time. The organizers (8) _________________ about 50,000 people, but as the (9) _________________ came nearer it became clear that far more people wanted to be at the event. A few days before the festival began hundreds of thousands of pop and rock fans were on their (10) _________________ to Woodstock. There were not enough gates where tickets were checked and fans made (11) _________________ in the fences, so lots of people just walked in. About 300,000 to 500,000 people were at the concert. The event caused a giant (12) _________________ jam. -

Vuosikertomus 2015 WIHURIN KANSAINVÄLISTEN PALKINTOJEN RAHASTON VUOSIKERTOMUS 2015 SISÄLLYSLUETTELO

Vuosikertomus 2015 WIHURIN KANSAINVÄLISTEN PALKINTOJEN RAHASTON VUOSIKERTOMUS 2015 SISÄLLYSLUETTELO 6 Wihurin kansainvälisten palkintojen rahasto Juhlavuosi 2015 8 Wihurin Sibelius-palkinto Palkinnonsaajat 1953-2015 10 Sir Harrison Birtwistle 12 Wihurin kansainvälinen palkinto Palkinnonsaajat 1958-2015 14 Thania Paffenholz 18 Talous ja hallinto Talous ja sijoitukset Viestintäuudistus Hallinto 20 Tuloslaskelma ja tase WIHURIN KANSAINVÄLISTEN PALKINTOJEN RAHASTO KALLIOLINNANTIE 4, 00140 HELSINKI 09 454 2400 WWW.WIHURIPRIZES.FI KANNEN KUVA: EMMA SARPANIEMI · GRAAFINEN SUUNNITTELU: WERKLIG · PAINO: GRANO © 2016 WIHURIN KANSAINVÄLISTEN PALKINTOJEN RAHASTO ALL PHOTOS ARE COPYRIGHTED TO THEIR RESPECTIVE RIGHTFUL OWNERS VALOKUVAT: JAAKKO KAHILANIEMI S. 7, 11, 15, 17, 19 (4) WIHURIN KANSAINVÄLISTEN PALKINTOJEN RAHASTON KUVA-ARKISTOT S. 8, 9, 12, 13 5 Wihurin kansainvälisten palkintojen rahasto Wihurin kansainvälisten palkintojen rahasto jakoi Wihurin Sibelius- palkinnon Sir Harrison Birtwistlelle ja Wihurin kansainvälisen palkin- non Ph.D Thania Paffenholzille 9. lokakuuta 2015 Finlandia- talossa ja toteutti näin tarkoitustaan ihmiskunnan henkisen ja taloudellisen kehityksen tukijana. Kumpikin palkinto oli määrältään 150 000 euroa. Wihurin kansainvälisten palkintojen rahaston pe- kintoa, joista 18 Wihurin kansainvälistä palkintoa rusti ja peruspääoman lahjoitti merenkulkuneuvos tieteentekijöille ja 17 Wihurin Sibelius-palkintoa Antti Wihuri vuonna 1953. Yleishyödyllisen sää- säveltäjille. Palkintojen suuruus on ollut nyky- tiön tarkoituksena on -

Open'er Festival

SHORTLISTED NOMINEES FOR THE EUROPEAN FESTIVAL AWARDS 2019 UNVEILED GET YOUR TICKET NOW With the 11th edition of the European Festival Awards set to take place on January 15th in Groningen, The Netherlands, we’re announcing the shortlists for 14 of the ceremony’s categories. Over 350’000 votes have been cast for the 2019 European Festival Awards in the main public categories. We’d like to extend a huge thank you to all of those who applied, voted, and otherwise participated in the Awards this year. Tickets for the Award Ceremony at De Oosterpoort in Groningen, The Netherlands are already going fast. There are two different ticket options: Premium tickets are priced at €100, and include: • Access to the cocktail hour with drinks from 06.00pm – 06.45pm • Three-course sit down Dinner with drinks at 07.00pm – 09.00pm • A seat at a table at the EFA awards show at 09.30pm – 11.15pm • Access to the after-show party at 00.00am – 02.00am – Venue TBD Tribune tickets are priced at €30 and include access to the EFA awards show at 09.30pm – 11.15pm (no meal or extras included). Buy Tickets Now without further ado, here are the shortlists: The Brand Activation Award Presented by: EMAC Lowlands (The Netherlands) & Rabobank (Brasserie 2050) Open’er Festival (Poland) & Netflix (Stranger Things) Øya Festivalen (Norway) & Fortum (The Green Rider) Sziget Festival (Hungary) & IBIS (IBIS Music) Untold (Romania) & KFC (Haunted Camping) We Love Green (France) & Back Market (Back Market x We Love Green Circular) European Festival Awards, c/o YOUROPE, Heiligkreuzstr. -

Discoursing Finnish Rock. Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-Ilmiö Rock Documentary Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2010, 229 P

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 140 Terhi Skaniakos Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 140 Terhi Skaniakos Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston vanhassa juhlasalissa S210 toukokuun 14. päivänä 2010 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S210, on May 14, 2010 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2010 Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 140 Terhi Skaniakos Discoursing Finnish Rock Articulations of Identities in the Saimaa-ilmiö Rock Documentary UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2010 Editor Erkki Vainikkala Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Paula Kalaja, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Tarja Nikula, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä Cover picture by Marika Tamminen, Museum Centre Vapriikki collections URN:ISBN:978-951-39-3887-1 ISBN 978-951-39-3887-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-3877-2 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright © 2010 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2010 ABSTRACT Skaniakos, Terhi Discoursing Finnish Rock. -

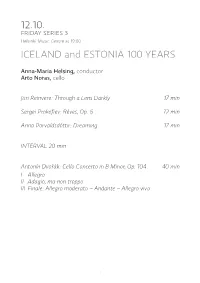

12.10. ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS

12.10. FRIDAY SERIES 3 Helsinki Music Centre at 19:00 ICELAND and ESTONIA 100 YEARS Anna-Maria Helsing, conductor Arto Noras, cello Jüri Reinvere: Through a Lens Darkly 17 min Sergei Prokofiev: Rêves, Op. 6 12 min Anna Þorvaldsdóttir: Dreaming 17 min INTERVAL 20 min Antonín Dvořák: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 40 min I Allegro II Adagio, ma non troppo III Finale: Allegro moderato – Andante – Allegro vivo 1 The LATE-NIGHT CHAMBER MUSIC will begin in the main Concert Hall after an interval of about 10 minutes. Those attending are asked to take (unnumbered) seats in the stalls. Paula Sundqvist, violin Tuija Rantamäki, cello Sonja Fräki, piano Antonín Dvořák: Piano Trio “Dumky” 31 min 1. Lento maestoso – Allegro vivace – Allegro molto 2. Poco adagio – Vivace 3. Andante – Vivace non troppo 4. Andante moderato – Allegretto scherzando – Allegro 5. Allegro 6. Lento maestoso – Vivace Interval at about 20:00. The concert will end at about 21:15, the late-night chamber music at about 22:00. Broadcast live on Yle Radio 1 and Yle Areena. It will also be shown in two parts in the programme “RSO Musiikkitalossa” (The FRSO at the Helsinki Music Centre) on Yle Teema on 21.10. and 4.11., with a repeat on Yle TV 1 on 27.10. and 10.11. 2 JÜRI REINVERE director became a close friend and im- portant mentor of the young compos- (b. 1971): THROUGH A er. Theirs was not simply a master-ap- LENS DARKLY prenticeship relationship, for they often talked about music, and Reinvere would Jüri Reinvere has been described as a sometimes express his own views as a true cosmopolitan with Estonian roots. -

New Students' Guide 2018

New Students' Guide 2018 University of the Arts Student Union PUBLISHER University of the Arts Student Union ArtSU RENEWED EDITION (2018) Riikka Pellinen PHOTOS Mikael Kinanen (cover, ArtSU’s anniversary party 2015) Tiitus Petäjäniemi (p. 17, the capping of Havis Amanda statue 2016) UNIARTS HELSINKI Helsinki 2018 2 DEAR NEW STUDENT, It is my pleasure to welcome you as a member of the University of the Arts Student Union ArtSU! You are currently reading your copy of the New Students’ Guide, a compact data pack- age put together by the Student Union and the organisation of the University of the Arts Helsinki (Uniarts Helsinki). It contains some important things you as a new stu- dent need to know. If you have any questions, you can look for additional information at the Uniarts Helsinki website, intranet Artsi, or ask your department/degree pro- gramme director or your tutor. There is no shame in asking! You, just like any other new student at Uniarts Helsinki, have been appointed a per- sonal student tutor. A tutor is an older student, who wants to direct and guide you dur- ing the coming autumn. Feel free to ask your tutor about anything related to student life, university practices or studies. All tutors have been trained by ArtSU, and your tutor will act as your guide to Uniarts Helsinki, Student Union activities, your own academy and your new fellow students. You will meet your tutor at the beginning of the new students’ orientation period. It is my goal and that of our tutors to make you feel at home in our student community. -

VIPNEWSPREMIUM > VOLUME 146 > APRIL 2012

11 12 6 14 4 4 VIPNEWS PREMIUM > VOLUME 146 > APRIL 2012 3 6 10 8 1910 16 25 9 2 VIPNEWS > APRIL 2012 McGowan’s Musings It’s been pouring with rain here for the last below normal levels. As the festival season weather! Still the events themselves do get couple of days, but it seems that it’s not the looms and the situation continues, we may covered in the News you’ll be glad to know. right type of rain, or there’s not enough of see our increasingly ‘green’ events having it because we are still officially in drought. to consider contingency plans to deal with I was very taken by the Neil McCormick River levels across England and Wales are the water shortages and yet more problems report in UK newspaper The Telegraph from lowest they’ve been for 36 years, since our caused by increasingly erratic weather. I’m the Coachella festival in California, as he last severe drought in 1976, with, according sure that many in other countries who still wrote, “The hairs went up on the back of my to the Environmental Agency, two-thirds picture England as a rain swept country neck…” as he watched the live performance ‘exceptionally ’ low, and most reservoirs where everybody carries umbrellas will find of Tupac Shakur…” This is perfectly it strange to see us indulging in rain dances understandable , as unfortunately, and not to over the next couple of months! put too fine a point on it, Tupac is actually dead. His apparently very realistic appearance Since the last issue of VIP News I have was made possible by the application of new journeyed to Canada, Estonia and Paris, and holographic projection technology. -

7 Questions for Harri Wessman Dante Anarca

nHIGHLIGHTS o r d i c 3/2016 n EWSLETTE r F r o M G E H r MA n S M U S i KFÖ r L A G & F E n n i c A G E H r MA n 7 questions for Harri Wessman dante Anarca NEWS Rautavaara in memoriam Colourstrings licensed in China Fennica Gehrman has signed an agreement with the lead- Einojuhani Rautavaara died in Helsinki on 27 July at the age ing Chinese publisher, the People’s Music Publishing of 87. One of the most highly regarded and inter nationally House, on the licensing of the teaching material for the best-known Finnish com posers, he wrote eight symp- Colourstrings violin method in China. The agreement honies, vocal and choral works, chamber and instrumen- covers a long and extensive partnership over publication of tal music as well as numerous concertos, orchestral works the material and also includes plans for teacher training in and operas, the last of which was Rasputin (2001–03). China. The Colourstrings method developed byGéza and Rautavaara’s international breakthrough came with his Csaba Szilvay has spread far and wide in the world and 7th symphony, Angel of Light (1994) , when keen crit- is regarded as a first-class teaching method for stringed ics likened him to Sibelius. His best-beloved orchestral instruments. work is the Cantus arcticus for birds and orchestra, for which he personally recorded the sounds of the birds. Apart from being an acclaimed composer, Rautavaara had a fine intellect, was a mystical storyteller and had a masterly command of words. -

Takemi Sosa Magnus Lindberg — Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy

Magnus Lindberg —Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy ACTA SEMIOTICA FENNICA Editor Eero Tarasti Associate Editors Paul Forsell Richard Littlefield Editorial Board Pertti Ahonen Jacques Fontanille André Helbo Pirjo Kukkonen Altti Kuusamo Ilkka Niiniluoto Pekka Pesonen Hannu Riikonen Vilmos Voigt Editorial Board (AMS) Márta Grabócz Robert S. Hatten Jean-Marie Jacono Dario Martinelli Costin Miereanu Gino Stefani Ivanka Stoianova TAKEMI SOSA Magnus Lindberg — Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy in Aura and the Symphonic Triptych Acta Semiotica Fennica LIII Approaches to Musical Semiotics 26 Academy of Cultural Heritages, Helsinki Semiotic Society of Finland, Helsinki 2018 E-mail orders [email protected] www.culturalacademy.fi https://suomensemiotiikanseura.wordpress.com Layout: Paul Forsell Cover: Harumari Sosa © 2018 Takemi Sosa All rights reserved Printed in Estonia by Dipri OÜ ISBN 978-951-51-4187-3 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-51-4188-0 (PDF) ISSN 1235-497X Acta Semiotica Fennica LIII ISSN 1458-4921 Approaches to Musical Semiotics 26 Department of Philosophy and Art Studies Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki Finland Takemi Sosa Magnus Lindberg — Musical Gesture and Dramaturgy in Aura and the Symphonic Triptych Doctoral Dissertation Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki (the main building), in auditorium XII on 04 May 2018 at 12 o’clock noon. For my Sachiko, Asune and Harunari 7 Abstract The Finnish composer Magnus Lindberg (b. 1958) is one of the leading figures in the field of contemporary classical music. Curiously, despite the fascinating characteristics of Lindberg’s works and the several interesting subjects his mu- sic brings up, his works have not been widely researched. -

The Clash and Mass Media Messages from the Only Band That Matters

THE CLASH AND MASS MEDIA MESSAGES FROM THE ONLY BAND THAT MATTERS Sean Xavier Ahern A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Kristen Rudisill © 2012 Sean Xavier Ahern All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor This thesis analyzes the music of the British punk rock band The Clash through the use of media imagery in popular music in an effort to inform listeners of contemporary news items. I propose to look at the punk rock band The Clash not solely as a first wave English punk rock band but rather as a “news-giving” group as presented during their interview on the Tom Snyder show in 1981. I argue that the band’s use of communication metaphors and imagery in their songs and album art helped to communicate with their audience in a way that their contemporaries were unable to. Broken down into four chapters, I look at each of the major releases by the band in chronological order as they progressed from a London punk band to a globally known popular rock act. Viewing The Clash as a “news giving” punk rock band that inundated their lyrics, music videos and live performances with communication images, The Clash used their position as a popular act to inform their audience, asking them to question their surroundings and “know your rights.” iv For Pat and Zach Ahern Go Easy, Step Lightly, Stay Free. v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the help of many, many people. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE presents A TESTAMENT TO THE SHEER JOY OF LIVING A LIFE OF SERVICE TO HUMANKIND AND OUR PLANET THE WAVY GRAVY MOVIE: SAINT MISBEHAVIN' RELEASES NOVEMBER 15 ON DIGITAL AND DVD An unforgettable trip through the extraordinary life of a poet, clown, activist and FUNdraiser “’Saint Misbehavin’’ is an unabashed love letter to the world that defies the cynicism of our age.” – The New York Times September 19, 2011 – “Some people tell me I’m a saint, I tell them I’m Saint Misbehavin’.” Poet, activist, entertainer, clown. These are a few ways to describe Wavy Gravy, an activist and prominent figure during the Woodstock era who continues to spread a message that we can make a difference in the world and have fun doing it! THE WAVY GRAVY MOVIE paints a moving and surprising portrait of his lifelong passion for peace, justice and understanding. The film features extensive verité footage and interviews with Wavy telling his own stories: from communal life with The Hog Farm, to his circus and performing arts camp, Camp Winnarainbow, to the epic cross-continent bus trip through Europe and South Asia that led to the founding of the Seva Foundation. Award-winning director Michelle Esrick weaves together this compelling film with rare footage from key events: Greenwich Village beat poets and folk music, Woodstock, non- violent protests, and many seminal moments of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and Wavy’s present day life. The Gaslight Café The year was 1958. The Vietnam War had just begun. Born as Hugh Romney, Wavy commanded the stage as a poet, comedian “tongue dancer,” and MC at The Gaslight Café in New York City’s Greenwich Village.