Shakespeare, Performance and Embodied Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Programme for Cheek by Jowl's Production of the Changeling

What does a cheek suggest – and what a jowl? When the rough is close to the smooth, the harsh to the gentle, the provocative to the welcoming, this company’s very special flavour appears. Over the years, Declan and Nick have opened up bold and innovative ways of work and of working in Britain and across the world. They have proved again and again Working on A Family Affair in 1988 that theatre begins and ends with opposites that seem Nick Ormerod Declan Donnellan irreconcilable until they march Nick Ormerod is joint Artistic Director of Cheek by Jowl. Declan Donnellan is joint Artistic Director of Cheek by Jowl. cheek by jowl, side by side. He trained at Wimbledon School of Art and has designed all but one of Cheek by As Associate Director of the National Theatre, his productions include Fuente Ovejuna Peter Brook Jowl’s productions. Design work in Russia includes; The Winter’s Tale (Maly Theatre by Lope de Vega, Sweeney Todd by Stephen Sondheim, The Mandate by Nikolai Erdman, of St Petersburg), Boris Godunov, Twelfth Night and Three Sisters (with Cheek by Jowl’s and both parts of Angels in America by Tony Kushner. For the Royal Shakespeare Company sister company in Moscow formed by the Russian Theatre Confederation). In 2003 he has directed The School for Scandal, King Lear (as the first director of the RSC Academy) he designed his first ballet, Romeo and Juliet, for the Bolshoi Ballet, Moscow. and Great Expectations. He has directed Le Cid by Corneille in French, for the Avignon Festival, Falstaff by Verdi for the Salzburg Festival and Romeo and Juliet for the Bolshoi He has designed Falstaff (Salzburg Festival), The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny Ballet, Moscow, becoming the first stage director to work with the Bolshoi Ballet since 1938. -

About Endgame

MONGREL MEDIA, BBC FILMS, TELEFILM CANADA, BORD SCANNÁN NA hÉIREANN/THE IRISH FILM BOARD, SODEC and BFI Present A WILDGAZE FILMS/ FINOLA DWYER PRODUCTIONS / PARALLEL FILMS / ITEM 7 co-production Produced in association with INGENIOUS, BAI, RTE And HANWAY FILMS BROOKLYN Directed by JOHN CROWLEY Produced by FINOLA DWYER and AMANDA POSEY Screenplay by NICK HORNBY Adapted from the novel by COLM TÓIBÍN Starring SAOIRSE RONAN DOMHNALL GLEESON EMORY COHEN With JIM BROADBENT And JULIE WALTERS Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com 1 INTRODUCTION BROOKLYN is the story of Eilis, a young woman who moves from small-town Ireland to Brooklyn, NY where she strives to forge a new life for herself, finding work and first love in the process. When a family tragedy brings her back to Ireland, she finds herself confronting a terrible dilemma - a heart-breaking choice between two men and two countries. Adapted from Colm Tóibín’s New York Times Bestseller by Nick Hornby (Oscar® nominee for An Education) and directed by John Crowley (Intermission, Boy A), BROOKLYN is produced by Finola Dwyer and Amanda Posey (Quartet, Oscar® nominees for An Education). BROOKLYN stars Saoirse Ronan (The Grand Budapest Hotel and Oscar® nominee for Atonement), Domhnall Gleeson (About Time, Anna Karenina), Emory Cohen (The Place Beyond The Pines), Jim Broadbent (Oscar® winner for Iris) and Julie Walters (Oscar® nominee for Billy Elliot and Educating Rita). -

Cavalleria Rusticana Pagliacci

cavalleriaPIETRO MASCAGNI rusticana AND pagliacciRUGGERO LEONCAVALLO conductor Cavalleria Rusticana Fabio Luisi Opera in one act production Libretto by Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti Sir David McVicar and Guido Menasci, based on a story set designer and play by Giovanni Verga Rae Smith Pagliacci costume designer Moritz Junge Opera in a prologue and two acts lighting designer Libretto by the composer Paule Constable Saturday, April 25, 2015 choreographer 12:30–3:45 PM Andrew George vaudeville consultant New Production (pagliacci) Emil Wolk The productions of Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci were made possible by generous gifts from M. Beverly and Robert G. Bartner, Mr. and Mrs. Paul M. Montrone, and the Estate of Anne Tallman general manager Peter Gelb Major funding was received from Rolex music director James Levine Additional funding was received from John J. Noffo Kahn principal conductor and Mark Addison, and Paul Underwood Fabio Luisi The 675th Metropolitan Opera performance of PIETRO MASCAGNI’S This performance cavalleria is being broadcast live over The rusticana Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera International Radio Network, sponsored conductor by Toll Brothers, Fabio Luisi America’s luxury in order of vocal appearance homebuilder®, with generous long-term turiddu support from Marcelo Álvarez The Annenberg santuzz a Foundation, The Eva-Maria Westbroek Neubauer Family Foundation, the mamma lucia Vincent A. Stabile Jane Bunnell Endowment for Broadcast Media, alfio and contributions George Gagnidze from listeners lol a worldwide. Ginger Costa-Jackson** There is no pe asant woman Toll Brothers– Andrea Coleman Metropolitan Opera Quiz in List Hall today. This performance is also being broadcast live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 74. -

“Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens's

“Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens’s Novels Marc Napolitano A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by Advisor: Allan Life Reader: Laurie Langbauer Reader: Tom Reinert Reader: Beverly Taylor Reader: Tim Carter © 2009 Marc Napolitano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Marc Napolitano: “Reviewing the Situation”: Oliver! and the Musical Afterlife of Dickens’s Novels (Under the direction of Allan Life) This project presents an analysis of various musical adaptations of the works of Charles Dickens. Transforming novels into musicals usually entails significant complications due to the divergent narrative techniques employed by novelists and composers or librettists. In spite of these difficulties, Dickens’s novels have continually been utilized as sources for stage and film musicals. This dissertation initially explores the elements of the author’s novels which render his works more suitable sources for musicalization than the texts of virtually any other canonical novelist. Subsequently, the project examines some of the larger and more complex issues associated with the adaptation of Dickens’s works into musicals, specifically, the question of preserving the overt Englishness of one of the most conspicuously British authors in literary history while simultaneously incorporating him into a genre that is closely connected with the techniques, talents, and tendencies of the American stage. A comprehensive overview of Lionel Bart’s Oliver! (1960), the most influential Dickensian musical of all time, serves to introduce the predominant theoretical concerns regarding the modification of Dickens’s texts for the musical stage and screen. -

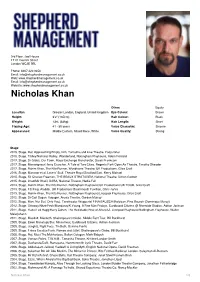

Nicholas Khan

3rd Floor, Joel House 17-21 Garrick Street London WC2E 9BL Phone: 0207 420 9350 Email: [email protected] Web: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk Email: [email protected] Website: www.shepherdmanagement.co.uk Nicholas Khan Other: Equity Location: Greater London, England, United Kingdom Eye Colour: Brown Height: 6'2" (187cm) Hair Colour: Black Weight: 13st. (83kg) Hair Length: Short Playing Age: 41 - 50 years Voice Character: Sincere Appearance: Middle Eastern, Mixed Race, White Voice Quality: Strong Stage 2019, Stage, Raf, Approaching Empty, Kiln, Tamasha and Live Theatre, Pooja Ghai 2018, Stage, Tilsley/Nicholas Ridley, Wonderland, Nottingham Playhouse, Adam Penford 2017, Stage, Dr Gibbs, Our Town, Royal Exchange Manchester, Sarah Frankcom 2017, Stage, Monseigneur/ Jerry Cruncher, A Tale of Two Cities, Regents Park Open Air Theatre, Timothy Sheader 2017, Stage, Rahim Khan, The Kite Runner, Wyndhams Theatre/ UK Productions, Giles Croft 2016, Stage, Mansoor et al, Love n' Stuff, Theatre Royal Stratford East, Kerry Michael 2015, Stage, Sir Charles Freeman, THE BEAUX STRATAGEM, National Theatre, Simon Godwin 2015, Stage, Imad/Mir Khalil, DARA, National Theatre, Nadia Fall 2014, Stage, Rahim Khan, The Kite Runner, Nottingham Playhouse/UK Productions/UK TOUR, Giles Croft 2013, Stage, PC Ping, Aladdin, UK Productions Bournmouth Pavillion, Chris Jarvis 2013, Stage, Rahim Khan, The Kite Runner, Nottingham Playhouse/Liverpool Playhouse, Giles Croft 2012, Stage, Dr Carl Sagan, Voyager, Arcola Theatre, Gordon Murray 2012, Stage, -

Gay News Photographic Archive

Gay News Photographic Archive (GNPA) ©Bishopsgate Institute Catalogued by Nicky Hilton September 2015 1 Table of Contents Page Collection Overview 3 GNPA/1 Cinemas 5 GNPA/2 Theatres 80 GNPA/3 Personalities and Events 90 GNPA/4 Miscellaneous 111 2 GNPA Gay News Photographic Archive (c.1972-1983) Name of Creator: Gay News Limited Extent: 37 folders Administrative/Biographical History: Gay News was a fortnightly newspaper in the United Kingdom founded in June 1972 in a collaboration between former members of the Gay Liberation Front and members of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE). At the newspaper's height, circulation was approximatly 18,000 copies. The original editorial collective included Denis Lemon (editor), Martin Corbett - who later was an active member of ACT UP, David Seligman, a founder member of the London Gay Switchboard collective, Ian Dunn of the Scottish Minorities Group, Glenys Parry (national chair of CHE), Suki J. Pitcher, and Doug Pollard, who later went on to launch the weekly gay newspaper, Gay Week (affectionately known as Gweek). Amongst Gay News' early "Special Friends" were Graham Chapman of Monty Python's Flying Circus, his partner David Sherlock, and Antony Grey, secretary of the UK Homosexual Law Reform Society from 1962 to 1970. Gay News was the response to a nationwide demand by lesbians and gay men for news of the burgeoning liberation movement. The paper played a pivotal role in the struggle for gay rights in the 1970s in the UK. It was described by Alison Hennegan (who joined the newspaper as Assistant Features Editor and Literary Editor in June 1977) as the movement's "debating chamber". -

Annual Report 2017–18

Annual Report 2017–18 1 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 2 Introduction During the 2017–18 season, the Metropolitan Opera presented more than 200 exiting performances of some of the world’s greatest musical masterpieces, with financial results resulting in a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses—the fourth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Bellini’s Norma and also included four other new productions, as well as 19 revivals and a special series of concert presentations of Verdi’s Requiem. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 12th year, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office and media) totaled $114.9 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All five new productions in the 2017–18 season were the work of distinguished directors, three having had previous successes at the Met and one making an auspicious company debut. A veteran director with six prior Met productions to his credit, Sir David McVicar unveiled the season-opening new staging of Norma as well as a new production of Puccini’s Tosca, which premiered on New Year’s Eve. The second new staging of the season was also a North American premiere, with Tom Cairns making his Met debut directing Thomas Adès’s groundbreaking 2016 opera The Exterminating Angel. -

Shakespeare's Isabella and Cressida on the Modern Stage

''Shrewd Tempters with their Tongues..,: Shakespeare's Isabella and Cressida on the Modern Stage Anna Kamaralli A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts, School of Theatre, Film and Dance of the University ofNSW In partial fulfillment of the degree ofMA(Hons) 2002 ii Abstract Shakespeare's Isabella (Measure for Measure) and Cressida (Troilus and Cressida) share an unusual critical and theatrical history. Unappreciated o:ri stage, contentious on the page, they have traditionally provoked discomfort among critics, wl).o l).ave ~~€::J:'! quicker to see them as morally reprehensible than to note their positive qualities. Seemingly at polar opposites of the personal and moral spectrum, the two share an independence of spirit, a refusal to conform to the desires and requirements of men, and a power to polarize opinion. This thesis considers the ways in which attitudes to Isabella and Cressida on the English speaking stage have shifted, over the latter half of the twentieth century, in the light of an escalating public awareness of issues of feminism and gender politics. Against a close reading of Shakespeare's text, both literary and performance criticism are examined, together with archival material relating to theatre productions of the plays, primarily by the Royal Shakespeare Company. The thesis concludes that in the case of both characters a change is indeed discemable. For Isabella, it is informed by the idea that the ethical code to which she adheres deserves respect, and that her marriage to the Duke is neither inevitable, nor inevitably welcomed by her. Cressida has undergone a more dramatic change: she is no longer assumed to be constitutionally immoral, and her behaviour is examined without preconception. -

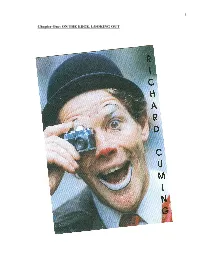

The Clown and the Institution

1 Chapter One: ON THE EDGE, LOOKING OUT 2 I was seven when my Mother’s father, Grandpa, took me down to the beach one summer’s day. I remember that we walked from our bungalow in Bournemouth, down to the front. I picture quite clearly the yellow trolley buses, like giant insects. I smell the crackle of the sparks of electricity from their arms, mingled with the sweetish smell of the sea. I see Grandpa, white hair sticking out from under his cap, horn-rimmed glasses, and a tweed overcoat, which he always wore. We wandered along the busy promenade, him pointing out interesting sights, just like Romany from ‘Out with Romany by the Sea.’ I read this a couple of years later, lying on a bunk in the back cabin of their houseboat when I stayed there one summer, whilst Mum was having another baby and Dad was up in London, working for the Admiralty. Reading the book, with its rough, red cardboard cover, embossed with gilt, was better than actually being by the sea. Yet I could smell the sea through the open porthole. And a faint smell of seaweed came from its mildew stained, cut pages. But this particular day was ‘Out with Romany by the Beach’ and was the real thing. He found a spot on the warm sand for us to sit down. Eventually he took off his coat, grudgingly admitting to the hot day, revealing a creased white short-sleeved shirt. I changed out of my clothes, pulled on my bathers, and started digging furiously with my spade. -

Oliver! at the London Palladium Photo: Michael Le Poer Trench

A SCENE FROM OLIVER! AT THE LONDON PALLADIUM PHOTO: MICHAEL LE POER TRENCH • Oliver! Robert Halliday joins the technical team at the London Palladium • Make Space! Ian Herbert on Manchester's major theatre design exhibit • Harman Audio: a profile of the sound giant's UK distribution arm • Going Interactive: a night out with Veronica in Utrecht • Superstar Rene Froger live at the Ahoy in Rotterdam • Club Review: new looks for the New Year JANUARY 1995 OLIVER! COMES BACK FOR MORE Rob HallidayLive at the Palladium By the time you read this, the show will no longer be 'Cameron Mackintosh's new £3.Sm production of Oliver!, the show won't be featured in every single Sunday supplement, and the London Palladium will no longer be awash with sub-contractors - though hopefully the ticket-touts and autograph seekerswill still be hanging around outside. Oliver! will have settled comfortably into the West End, delighting eight audiences a week with its excellent performances and good tunes. For me, the memories of the production period, the previews, the star-studded first night and, of course, the first night party are still fresh - if slightly hazy in the case of the party! Oliver! may be a classic musical, known and loved by a large percentage of the British population, famous for the revolutionary scenic design of its original, 1960 production and immortalised on film. But, as the hype made clear, this was a new production, produced on the largest scale in the style established by a decade of new musicals from the Andrew Lloyd Webber and Cameron Mackintosh stables. -

SCHERZO DISCOS Sumario LIBROS 158 113 DOSIER LA GUÍA 160 Darwinismo Y Música CONTRAPUNTO Norman Lebrecht 164 Colaboran En Este Número

REVISTA DE MÚSICA Año XXIV - Nº 243 - Julio - Agosto 2009 - 7 € DOSIER Darwinismo y música Año XXIV - Nº 243 Julio Agosto 2009 ENCUENTROS Ottavio Dantone Emilio Sagi y Jesús López Cobos ACTUALIDAD Maria João Pires REFERENCIAS Sinfonía clásica de Prokofiev 243-pliego 1.FILM:207-pliego 1 24/6/09 15:20 Página 1 AÑO XXIV - Nº 243 - Julio-Agosto 2009 - 7 € 2 OPINIÓN Música y evolución José Luis Carles 114 CON NOMBRE Música animal, música PROPIO humana 6 Maria João Pires Ramón Andrés 118 Emili Blasco El origen de la música Javier Arias Bal 122 8 AGENDA De El origen de las especies a la historiografía musical Beatriz C. Montes 126 18 ACTUALIDAD NACIONAL ENCUENTROS 44 ACTUALIDAD Ottavio Dantone Franco Soda 142 INTERNACIONAL Jesús López Cobos y Emilio Sagi 58 ENTREVISTA Arturo Reverter 148 Manfred Eicher Mark Wiggins EDUCACIÓN Pedro Sarmiento 154 64 Discos del mes JAZZ Pablo Sanz 156 65 SCHERZO DISCOS Sumario LIBROS 158 113 DOSIER LA GUÍA 160 Darwinismo y Música CONTRAPUNTO Norman Lebrecht 164 Colaboran en este número: Javier Alfaya, Daniel Álvarez Vázquez, Julio Andrade Malde, Ramón Andrés, Íñigo Arbiza, Javier Arias Bal, Emili Blasco, Alfredo Brotons Muñoz, José Antonio Cantón, José Luis Carles, Jacobo Cortines, Patrick Dillon, Pierre Élie Mamou, José Luis Fernández, Fernando Fraga, Germán Gan Quesada, Manuel García Franco, José Antonio García y García, Juan García-Rico, José Guerrero Martín, Fernando Herrero, Bernd Hoppe, Paul Korenhof, Antonio Lasierra, Norman Lebrecht, Fiona Maddocks, Bernardo Mariano, Santiago Martín Bermúdez, Joaquín Martín de Sagarmínaga, Enrique Martínez Miura, Aurelio Martínez Seco, Blas Matamoro, Erna Metdepenninghen, Beatriz C.