A Narrative Criticism of Edutainment Television Programming BY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCSM Program Book (1).Indd 1 3/21/2011 10:24:52 AM President’S Message

Ad pages (mlw).indd 21 3/20/2011 11:52:33 PM Table of Contents Welcome Messages 2, 3 Conference Schedule Overview 9 Program Support Committees 4 Program Overview 5 General Information NCSM Annual Conference Sponsor Partners 7 National Council of Supervisors of Caucuses 6 Commercial Sessions 7 Mathematics Conference Badges and Bags 6 mathedleadership.org Conference Feedback 8 Conference Planner 6 Emergency Information 6 Fire Code 6 On Track for Student Success: Local Attractions & Restaurants 8 Mathematics Leaders Making a Difference Lost and Found 8 NCTM Bookstore and Research Presession 8 43rd NCSM Annual Conference NCSM Business Meeting 6 April 11–13, 2011 Non-Smoking Policy 6 Session Changes 6 Session Seating 6 Registration Sponsor Display Area 7 Registration takes place the JW Marriott, Level Two, at the Student Recognition Certificates 8 Taping, Recording, or Photographing Sessions 6 following times: Ticketed Functions 7 Sunday, April 10 2:00 PM to 7:00 PM Tips for a Successful Conference Experience 6 Monday, April 11 6:45 AM to 5:00 PM Program Summary Information Monday 11 Tuesday, April 12 6:45 AM to 12:30 PM Tuesday 35 2:30 PM to 5:00 PM Wednesday 59 Wednesday, April 13 7:30 AM to 10:30 AM Full Program Details Monday 19 Tuesday 43 Sponsor Display Area Wednesday 65 NEW THIS YEAR—EXTENDED DISPLAY HOURS ON About NCSM MONDAY NCSM Grants, Awards, and Certificates 82 Over Four Decades of NCSM Presidents 78 Visit elite NCSM Sponsor Partners in Griffin Hall, Level Two Important Future NCSM Dates 82 of the JW Marriott, during the following -

To Return to Campus Next Month Friday 82˚

Thursday, July 16, 2020 Vol. 19 No. 15 OBITUARIES COMMENTARY NEWS HEALTH Mourning local Plagued by illegal Roybal-Allard Rite Aid now deaths fireworks targets FAA offers testing SEE PAGE 2 SEE PAGE 3 SEE PAGE 7 SEE PAGE 11 Students ‘highly unlikely’ to return to campus next month Friday 82˚ Following the lead of pending decisions to be made Saturday 84˚ LAUSD, Downey officials at the Board of Educations upcoming July 20 meeting. said students will likely start the fall semester at The superintendent for the home. Los Angeles Unified School Sunday 86˚ District announced Monday that students will not return to the classroom when the fall semester DOWNEY — Students will begins next month. likely not be returning to school ON THIS DAY campuses at the start of the Along with LAUSD, the San school year, according to the Diego Unified School District will JULY 16 Downey Unified School District. also begin its fall semester in a virtual format. The two districts 1769: With many COVID-19 related released a joint statement Father Junipero Serra founded regulations in constant flux, confirming the move. California’s first mission, Mission San DUSD has spent most of the Diego de Alcala. Over the following summer with very few answers “Both districts will continue decades, it evolved into the city of San as to how the upcoming school planning for a return to in- Diego. year might look. person learning during the 2020- 21 academic year, as soon as 1861: It was only recently the public health conditions allow,” Under orders from President Abraham district released some sort of the statement read. -

2 September 2016

SEPTEMBER 2 - SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 VOL. 33 - ISSUE 18 ORANGE BLOSSOM FESTIVAL 17 - 18 SEPTEMBER CASTLE HILL SHOWGROUND Orange Blossom Festival is back with rides, kids zone, markets, foods, live entertainment, community stalls, fireworks, parade and so much more. For more details visit www. orangeblossomfestival.com.au BOUTIQUE FURNITURE Sandstone AND GIFTS Sales MARK VINT Buy Direct From the Quarry 9651 2182 Mention code QCHS0616 for 270 New Line Road 10% off the online rate 9652 1783 Dural NSW 2158 Specialising in corporate and [email protected] leisure accommodation. Handsplit ABN: 84 451 806 754 Group bookings available including sports groups, wedding guest groups, etc Random Flagging $55m2 Shop 1, 940 Old Northern Road, Glenorie, NSW 2157 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie WWW.DURALAUTO.COM (02) 9652 2552 Ph 02 88481500 ELECTRICIAN Domestic & Commercial Lighting, Powerpoints, Sensor Lights, Ceiling Fans, Smoke Detectors, Hot Water. No job too big or small 9680 2400 Timely, Tidy & Trusted™ 1300 045 103 Lic. No. 180022C An eclectic oasis in the heart of Glenorie FUSION ART • PHOTOGRAPHY • VINTAGE COLLECTIBLES An eclectic oasis in the heart of Glenorie Run and operated by the artists Ulla and Bjorn The UB Art Shack 2 Cairnes Road, Glenorie NSW 2157 Thur & Fri 12pm - 5pm, Sat & Sun 10am - 5pm 唀䈀 䄀爀琀 匀栀愀挀欀 Ph: Ulla - 0414 180 971 or Bjorn - 0419 242 844 E: [email protected] W: www.ubartshack.com.au FB: Ulla and Bjorn’s Art Shack MENTIONBUY A THIS DOZEN, AD QUALITY WINES, & RECEIVE 2 FREE CRAFT BEERS & SPIRITS BOTTLES FAMILY OWNED AND OPERATED 1669 Old Northern Road Glenorie | Ph 1300 76 78 73 IN THIS ISSUE CONTENTS In This Issue 3 Memories 5 Living Legends 7 History 12 Health & Wellbeing 13 Your Garden 15 As We Were 17 Local Politicians Say 23 The Hills & Beyond 25 The Greying Nomad 27 Hill’s Sustainable Communities Conference with Robyn Moore LETTER FROM THE EDITOR’S DESK Community Groups 28 Congratulations to Laura Rittenhouse who is our first winner of the My Garden competition. -

Sandstone Sales

AUGUST 19 - SEPTEMBER 4, 2016 VOL. 33 - ISSUE 17 PRIDE OF BAULKHAM HILLS - TOM BURTON WINS GOLD IN MEN’S LASER Congratulations to Tom Burton points ahead at the finish. “I for winning Gold for Australia in sailed out of my skin to get the the men’s Laser Class Sailing. job done” he said. Tom went into the final, of Another big congratulations to ten races, five points down. He Baulkham Hills sailor, Cameron managed to outperform rivals Girdlestone, who won silver in to finish third, placing him two the men’s Quad Scull. Sandstone 2-4 SEPTEMBER 2016 Sales MARK VINT Buy Direct From the Quarry 9651 2182 2-4 SEPTEMBER 2016 D270E KNewO LineDA Road EXHIBITION & EVENTS 9652 1783 Dural NSW 2158 [email protected] Handsplit ABN: 84 451 806 754 DEKODA EXHIBITION & EVENTS Random Flagging $55m2 113 Smallwood Rd Glenorie WWW.DURALAUTO.COM © SAILING ENERGY / WORLD SAILING LOGSPLITTERS CHAINSAWS RIDE ONS & MOWERS SALES & SERVICE Chains Mowers & Chainsaws 9627 9999 1586 Windsor Rd Vineyard 9680 2400 2-4 SEPTEMBER 2016 Rug Collection centre GRAND OPENING All Half CaDEsKOtDA lEXeHIB ITHIONi &l EVlEN TSS howgrounds Persian handmade silk and wool rugs from around the world, plus shags, modern and traditional machine Bring Price Harvey Lowe Pavilion made rugs. Runners all sizes, colours and designs this ad and available. Certified valuation available on all rugs. purchase over $390 to receive 10am-4pm $5 Entry Behind NOW OPEN 7 DAYS a further 5% Car Net 10am-5pm discount (02) 9674 4488 17/5B Curtis Rd, Mulgrave | Ph 0404 803 304 / 02 4577 6643 989 -

Super ACRONYM 2 - Round 7

Super ACRONYM 2 - Round 7 1. Somewhat specific answer required. In a 2009 parody for The Kevin Bishop Show, Karen Gillan sang about the reasons for this action, including "to have a hit." Keith Urban described wanting to "make a little magic in the moonlight" in a song titled for taking this action. In another song, a woman declares "we had a drink, we had a smoke" shortly before taking this action. The singer of that song noted that this action (*) "won't change the world, but I'm so glad." In a song from a 1989 Disney film, the singer insists that it "don't take a word" to take this action, which titled the only hit for singer Jill Sobule. In another song, "cherry chapstick" is tasted during, for 10 points, what amorous action, about which Katy Perry claimed "I liked it"? ANSWER: kissing a girl (accept I Kissed a Girl or Kiss the Girl or reasonably similar things; prompt on "kiss(ing)") <Nelson> 2. In one of his first TV appearances, this figure was beaten up by Ricky Gervais in the cold open of a 2018 episode of The Tonight Show. In a 2018 incident at the Adventure Aquarium, this figure was filmed ripping dozens of plush sharks from the shelf of a gift shop before jumping on them. This character was introduced at the Please Touch Museum and was the first of his kind since a bespectacled character from the 1970s who wore a similar black (*) helmet. John Oliver described this character as "the end product of the McDonald's fry guy hooking up with Grimace." A great version of a meme reading "Good Night, Alt Right" features a Pepe being beaten by, for 10 points, what orange, googly-eyed mascot of the Philadelphia Flyers? ANSWER: Gritty <Vitello> 3. -

Shaw Media Dominates Specialty Television with Massive New Series and Record-Breaking Returning Hits in 2014/15 Programming Lineup

SHAW MEDIA DOMINATES SPECIALTY TELEVISION WITH MASSIVE NEW SERIES AND RECORD-BREAKING RETURNING HITS IN 2014/15 PROGRAMMING LINEUP Blockbuster Series Outlander Debuts on Showcase Sunday, August 24 Canadian Mega Hits Vikings, Timber Kings, and Chopped Canada Return with New Seasons Star-Studded Series and Specials Light Up the Schedule with Adrien Brody, Kristen Connolly, Ellen DeGeneres, Minnie Driver, Brendan Fraser, Anthony Head, Kris Kristofferson, Ray Liotta, Olivier Martinez, Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Bill Paxton, William Shatner, and More New Channel Brands – FYI™ and Crime + Investigation™ (CI) – Bolster Shaw Media’s Dynamic Specialty Offerings For additional photography and press kit material visit: http://www.shawmedia.ca/media and follow us on Twitter at @shawmediaTV_PR For Immediate Release TORONTO, June 3, 2014 – Shaw Media today announced its powerful lineup of colossal premieres and returning hits anchoring its 2014/2015 schedule. This past broadcast year, Shaw Media owned four of the Top 10 and seven of the Top 20 specialty channels*, more than any other Canadian broadcaster. After claiming 14 of the top 20 specialty program spots** this year, Shaw Media solidifies its position as the leading specialty content provider with an aggressive slate of original content and blockbuster premieres, adding over 50 new series, over 90 returning series, and two new channel brands to the powerhouse portfolio. “Shaw Media consistently delivers top performing specialty content year after year,” said Barbara Williams, Senior Vice President, Content, Shaw Media. “With a stellar slate of new series and a lineup that celebrates proven homegrown successes, Shaw Media is set to once again dominate the industry as the home for top specialty content in Canada.” A top destination for the biggest and boldest series, Showcase’s fall schedule is headlined by two of the most buzzed about new specialty dramas. -

Robotics and Automated Systems

14 OPTION Robotics and automated systems CHAPTER OUTCOMES KEY TERMS You will learn about: Actuators Magnetic gripper • the history of robots and robotics output devices, such as motors type of end effector used to pick and end effectors, that convert up metallic objects • different types of robots energy and signals to motion Motion sensor • the purpose, use and function of Automated control system automated control component robots group of elements that maintains that detects sudden changes of • automated control systems a desired result by manipulating movement • input, output and processing the value of another variable in Optical sensor devices associated with automated the system automated control component control systems. Controller that detects changes in light or in You will learn to: processes information from colour sensors and transmits appropriate • defi ne and describe robots, Robot commands to actuators in robotics and automated control automatically guided machine automated systems systems that is able to perform tasks on Cyborgs its own • examine and discuss the purpose humans who use mechanical or Robotics of robots and hardware devices electromechanical technology to associated with robots science of the use and study of give them abilities they would not robots • examine and discuss hardware otherwise possess Sensor devices associated with automated Degrees of freedom control systems input device that accepts data measure of robotic motion—one from the environment • investigate robotic and automated degree of freedom is equal to one Solenoid control systems. movement either back and forth type of actuator that produces (linear movement) or around in a movement using a magnetic circle (rotational) current End effector Temperature sensor mechanical device attached to the automated control component end of a robotic arm that carries that measures temperature out a particular task 280 IN ACTION Electric humans The combination of artifi cial materials within the body has long fascinated humans and been the basis for captivating science fi ction. -

(2012) the Girl Who Kicked the Hornets Nest (2009) Super

Stash House (2012) The Girl Who Kicked The Hornets Nest (2009) Super Shark (2011) My Last Day Without You (2011) We Bought A Zoo (2012) House - S08E22 720p HDTV The Dictator (2012) TS Ghost Rider Extended Cut (2007) Nova Launcher Prime v.1.1.3 (Android) The Dead Want Women (2012) DVDRip John Carter (2012) DVDRip American Pie Reunion (2012) TS Journey 2 The Mysterious Island (2012) 720p BluRay The Simpsons - S23E21 HDTV XviD Johnny English Reborn (2011) Memento (2000) DVDSpirit v.1.5 Citizen Gangster (2011) VODRip Kill List (2011) Windows 7 Ultimate SP1 (x86&x64) Gone (2012) DVDRip The Diary of Preston Plummer (2012) Real Steel (2011) Paranormal Activity (2007) Journey 2 The Mysterious Island (2012) Horrible Bosses (2011) Code 207 (2011) DVDRip Apart (2011) HDTV The Other Guys (2010) Hawaii Five-0 2010 - S02E23 HDTV Goon (2011) BRRip This Means War (2012) Mini Motor Racing v1.0 (Android) 90210 - S04E24 HDTV Journey 2 The Mysterious Island (2012) DVDRip The Cult - Choice Of Weapon (2012) This Must Be The Place (2011) BRRip Act of Valor (2012) Contagion (2011) Bobs Burgers - S02E08 HDTV Video Watermark Pro v.2.6 Lynda.com - Editing Video In Photoshop CS6 House - S08E21 HDTV XviD Edwin Boyd Citizen Gangster (2011) The Aggression Scale (2012) BDRip Ghost Rider 2 Spirit of Vengeance (2011) Journey 2: The Mysterious Island (2012) 720p Playback (2012)DVDRip Surrogates (2009) Bad Ass (2012) DVDRip Supernatural - S07E23 720p HDTV UFC On Fuel Korean Zombie vs Poirier HDTV Redemption (2011) Act of Valor (2012) BDRip Jesus Henry Christ (2012) DVDRip -

Super ACRONYM - Round 12

Super ACRONYM - Round 12 1. Immediately before this event, a similar but less publicized act took place between its central figure and Troy Santiago. A man discussed in this event responded to it by noting "film don't lie" in a tweet that also used the hashtag #fake three times. In response to this event, Andre Iguodala claimed "we just got sent back 500 years." This event's central figure, who was (*) asked "who was talking about you?," ended his remarks by shouting "L.O.B.!" and had earlier used the adjective "sorry" to describe a former Texas Tech wideout. Erin Andrews was one participant in, for 10 points, what legendary 2014 outburst by a Seahawks cornerback? ANSWER: Richard Sherman's post-game interview after the 2014 NFC Championship game (accept reasonable descriptions of Richard Sherman giving a rant to Erin Andrews or going off on Michael Crabtree or similar) <Nelson> 2. A rapper known by this name had a top ten hit in 1990 with the song "Knockin' Boots." On an episode of Fringe, a serial kidnapper with this name temporarily abducts a child once every two years. A guy described by this name is "a one stop shop" who "makes my cherry pop" according to a song by Christina (*) Aguilera. Tony Todd played a film character with this name in a series whose sequels include one subtitled "Farewell to the Flesh." In a namesake song from a 1971 film, this man is the answer to the question "who can take a sunrise, sprinkle it with dew?" For 10 points, give this name that describes Willy Wonka. -

Q3 2011 Quarterly Supplemental Data

Q3 2011 QUARTERLY SUPPLEMENTAL DATA Q3:11 TOTAL PROGRAMMING DAY DELIVERY SELECT ORIGINAL PROGRAMMING FOR 2011-2012 (cont) Network Key Demo Delivery (‘000) Premiere 1 TNT A25-54 527 Series Network Season Date TBS A18-49 414 Regular Show Cartoon Network 3 9/19/11 truTV A18-49 349 Secret Mountain CNN A25-54 158 Fort Awesome Cartoon Network 1 9/26/11 HLN A25-54 150 China, IL Adult Swim 1 10/2/11 Cartoon Network K2-11 663 Top 20 Most Shocking truTV 5 10/6/11 Tyler Perry’s Adult Swim A18-34 554 House of Payne TBS 5 10/21/11 2 Source: Nielsen Media Research Robot Chicken Adult Swim 5 10/23/11 2 truTV Presents: Q3:11 DIGITAL PROPERTIES World’s Dumbest truTV 12 10/27/11 Average Monthly Tyler Perry’s Domestic Unique Meet the Browns TBS 4 10/28/11 2 Properties Visitors (in M)1 The Heart, She Holler Adult Swim 1 11/6/11 3 3 2 Police POV truTV 2 11/6/11 CNN Digital Network 73.6 3 3, 4 Conan TBS 2 11/7/11 Turner - SI Digital 18.3 3 5 Generator Rex Cartoon Network 3 11/11/11 Turner Entertainment Digital 17.8 3 6 Lizard Lick Towing truTV 2 11/14/11 Turner Sports & Entertainment 34.2 3 7 Hardcore Pawn truTV 5 11/15/11 Turner Digital 91.8 Storage Hunters truTV 1 11/15/11 2, 3 1 Average for the quarter ended September 30, 2011. For Better or Worse TBS 1 11/25/11 3 2, 3 2 CNN Digital Network includes CNN .com, CNN Money.com, EW.com, Time.com, Leverage TNT 4 11/27/11 the IB-CNN Websites Channel and People.com. -

Legal Media Email Distribution

Legal Media Email Distribution A Georgia Lawyer Islamic Law and Society A&B Blawg Briefs Islamic Law In Our Times ABA Journal IStR - Internationales Steuerrecht ABA Journal Online IT Law Today ABA Trust Letter It-Recht Kanzlei ABA Washington Letter, The ITC Law Blog ABA Washington Summary Jaffe Legal News Service, The ABLawg JCR: Journal of Court Reporting Aboriginal Law Blog Jiangsu Law News Above The Law Jim Calloway's Law Practice Tips Blog ACC Docket John Marshall Law Review ACC Docket Online JONA's Healthcare Law, Ethics & Regulation Acumen Law Corporation Jordans Company Law News and Comment Ad Law Access Jordans Employment Law News and Comment Adask's Law Jordans Family Law News and Comment Adjunct Law Prof Blog Jordans Insolvency Law News and Comment Adlaw By Request Jordans Public Law News and Comment Administrative & Regulatory Law News Jordans' Competition Law News & Comment Administrative Law Review Jordans' Private Client Law News & Comment Advisor Today Jottings By An Employer's Lawyer Advisor Today Blog JOURNAL DE DROIT FISCAL AdvisorHub Journal of Comparative Law Advisory, The Journal of Corporation Law Advocate Journal Of Criminal Justice Advocate, The (3) Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology African Law & Business Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law (2) Agricultural Law Journal of Environmental Law Air & Space Law Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine Akron Legal News Journal of Health Politics,Policy and Law Akron Legal News - Online Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice Alabama Appellate Watch Journal -

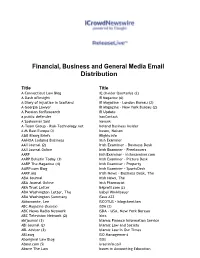

Email Distribution

Financial, Business and General Media Email Distribution Title Title A Connecticut Law Blog IQ (Insider Quarterly) (2) A Dash ofInsight IR Magazine (6) A Diary of Injustice in Scotland IR Magazine - London Bureau (2) A Georgia Lawyer IR Magazine - New York Bureau (2) A Passion forResearch IR Update a public defender IranContact A Spokesman Said Iravunk A-Team Group - Risk-Technology.net Ireland Business Insider A.M. Best Europe (2) Ireson, Nelson A&B Blawg Briefs iRights.info AAHOA Lodging Business Irish Examiner AAII Journal (2) Irish Examiner - Business Desk AAII Journal Online Irish Examiner - Freelancers AARP Irish Examiner - irishexaminer.com AARP Bulletin Today (3) Irish Examiner - Picture Desk AARP The Magazine (4) Irish Examiner - Property AARP.com Blog Irish Examiner - SportsDesk AARP.org Irish News - Business Desk, The ABA Journal Irish News, The ABA Journal Online Irish Pharmacist ABA Trust Letter Is4profit.com (2) ABA Washington Letter, The Isabel Winklbauer ABA Washington Summary iSave A2Z Abbamonte, Lee ISCOTUS - blogskentlaw ABC Magazine (Sussex) ISDA (2) ABC News Radio Network ISDA - USA, New York Bureau ABC Television Network (2) Iskra abfjournal (3) Islamic Finance Information Service ABI Journal (2) Islamic Law and Society ABL Advisor (3) Islamic Law In Our Times ABLawg ISO Management Aboriginal Law Blog ISOS About.com (5) israelinfo.co.il Above The Law Issues in Accounting Education Above the Market IST Magazine Absolute Return IStR - InternationalesSteuerrecht Absolute UCITS (2) Isurus (2) ACC Docket IT Europa ACC