British Social Class As Reflected in the Novels of P. G. Wodehouse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inimitable Jeeves Free

FREE THE INIMITABLE JEEVES PDF P. G. Wodehouse | 253 pages | 30 Mar 2007 | Everyman | 9781841591483 | English | London, United Kingdom The Inimitable Jeeves (Jeeves, #2) by P.G. Wodehouse Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want The Inimitable Jeeves Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us The Inimitable Jeeves the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — The Inimitable Jeeves by P. The Inimitable Jeeves Jeeves 2 by P. When Bingo Little falls in love at a Camberwell subscription dance and Bertie Wooster drops into the mulligatawny, there is work for a wet-nurse. Who better than Jeeves? Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published July 5th by W. Norton Company first published More Details Original Title. Jeeves 2The Drones Club. The Inimitable JeevesBrookfieldCuthbert DibbleW. BanksHarold Other Editions Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about The Inimitable Jeeves The Inimitable Jeeves, please sign up. Adam Schuld The book is available The Inimitable Jeeves Epis! If I were to listen to this as an audiobook, who is the best narrator? If you scroll to the bottom of the page, you can stream it instead of downloading. See 2 questions about The Inimitable Jeeves…. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of The Inimitable Jeeves Jeeves, 2. In addition, the book has the disadvantage of pretending The Inimitable Jeeves be a novel, even though it is obviously a collection of short stories, with most of the seven stories separated into two distinct chapters. -

Westminster Abbey South Quire Aisle

Westminster Abbey South Quire Aisle The Dedication of a Memorial Stone to P G Wodehouse Friday 20th September 2019 6.15 pm HISTORICAL NOTE It is no bad thing to be remembered for cheering people up. As Pelham Grenville Wodehouse (1881–1975) has it in his novel Something Fresh, the gift of humour is twice blessed, both by those who give and those who receive: ‘As we grow older and realize more clearly the limitations of human happiness, we come to see that the only real and abiding pleasure in life is to give pleasure to other people.’ Wodehouse dedicated almost 75 years of his professional life to doing just that, arguably better—and certainly with greater application—than any other writer before or since. For he never deviated from the path of that ambition, no matter what life threw at him. If, as he once wrote, “the object of all good literature is to purge the soul of its petty troubles”, the consistently upbeat tone of his 100 or so books must represent one of the largest-ever literary bequests to human happiness by one man. This has made Wodehouse one of the few humourists we can rely on to increase the number of hours of sunshine in the day, helping us to joke unhappiness and seriousness back down to their proper size simply by basking in the warmth of his unique comic world. And that’s before we get round to mentioning his 300 or so song lyrics, countless newspaper articles, poems, and stage plays. The 1998 edition of the Oxford English Dictionary cited over 1,600 quotations from Wodehouse, second only to Shakespeare. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Autumn-Winter 2002

Beyond Anatole: Dining with Wodehouse b y D a n C o h en FTER stuffing myself to the eyeballs at Thanks eats and drinks so much that about twice a year he has to A giving and still facing several days of cold turkey go to one of the spas to get planed down. and turkey hash, I began to brood upon the subject Bertie himself is a big eater. He starts with tea in of food and eating as they appear in Plums stories and bed— no calories in that—but it is sometimes accom novels. panied by toast. Then there is breakfast, usually eggs and Like me, most of Wodehouse’s characters were bacon, with toast and marmalade. Then there is coffee. hearty eaters. So a good place to start an examination of With cream? We don’t know. There are some variations: food in Wodehouse is with the intriguing little article in he will take kippers, sausages, ham, or kidneys on toast the September issue of Wooster Sauce, the journal of the and mushrooms. UK Wodehouse Society, by James Clayton. The title asks Lunch is usually at the Drones. But it is invariably the question, “Why Isn’t Bertie Fat?” Bertie is consistent preceded by a cocktail or two. In Right Hoy Jeeves, he ly described as being slender, willowy or lissome. No describes having two dry martinis before lunch. I don’t hint of fat. know how many calories there are in a martini, but it’s Can it be heredity? We know nothing of Bertie’s par not a diet drink. -

Aunts Aren't What?

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 27 Number 3 Autumn 2006 Aunts Aren’t What? BY CHARLES GOULD ecently, cataloguing a collection of Wodehouse novels in translation, I was struck again by R the strangeness of the title Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen and by the sad history that seems to dog this title and its illustrators, who in my experience always include a cat. Wodehouse’s original title is derived from the dialogue between Jeeves and Bertie at the very end of the novel, in which Bertie’s idea that “the trouble with aunts as a class” is “that they are not gentlemen.” In context, this is very funny and certainly needs no explication. We are well accustomed to the “ungentlemanly” behavior of Aunt Agatha—autocratic, tyrannical, unreasoning, and unfair—though in this instance it’s the good and deserving Aunt Dahlia whose “moral code is lax.” But exalted to the level of a title and thus isolated, the statement A sensible Teutonic “aunts aren’t gentlemen” provokes some scrutiny. translation First, it involves a terrible pun—or at least homonymic wordplay—lost immediately on such lost American souls as pronounce “aunt” “ant” and “aren’t” “arunt.” That “aunt” and “aren’t” are homonyms is something of a stretch in English anyway, and to stretch it into a translation is hopeless. True, in “The Aunt and the Sluggard” (My Man Jeeves), Wodehouse wants us to pronounce “aunt” “ant” so that the title will remind us of the fable of the Ant and the Grasshopper; but “ants aren’t gentlemen” hasn’t a whisper of wit or euphony to recommend it to the ear. -

MAYFAIR W1 an Extremely Rare Mixed-Use Development Opportunity in the Heart of Mayfair INVESTMENT SUMMARY

MAYFAIR W1 An extremely rare mixed-use development opportunity in the heart of Mayfair INVESTMENT SUMMARY Freehold; • An extremely rare opportunity to develop a prime, mixed-use building in the centre of Mayfair; • Exceptional location to the east of Hanover Square, London’s most desirable corporate address; • Positioned less than 150 metres from the entrance to Bond Street Crossrail station, due to be operational from December 2018; • Well-placed to exploit the micro-location’s uplift in footfall on completion of Crossrail and the Hanover Square Masterplan; • Existing mixed-use building comprises 10,215 sq ft (NIA) of stripped-out, vacant accommodation; • Property benefits from valuable planning consent for a n extension of the office element, and conversion of the lower floors to rare restaurant (A3) use; • Consented office element includes six floors of efficient, Grade A accommodation that benefit from exceptional natural light; • Proposed restaurant features private dining space at first floor level and prominent ground floor space that is well suited to high-end operators; • Suitable as a trophy headquarter office premises for owner occupiers, or a range of alternative uses, subject to planning consents; • Offers are invited in excess of £18,500,000, subject to contract, which reflects a capital value of £1,811 per sq ft (existing). CGI 4 5 ST JAMES’S REGENT GREEN BERKELEY HANOVER BOND OXFORD GROSVENOR SQUARE STREET PARK SQUARE SQUARE STREET STREET SQUARE 6 7 LOCATION LOCAL OCCUPIERS Mayfair is internationally recognised OFFICES RESTAURANTS HOTELS & CLUBS as London’s most desirable residential, 1 Apollo Management 1 Wild Honey 1 The Westbury retail and office location. -

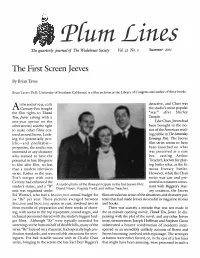

The First Screen Jeeves

Plum L in es The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Vol. 22 No. 2 Summer 2001 The First Screen Jeeves By Brian Taves Brian Taves (PhD, University of Southern California) is a film archivist at the Library of Congress and author of three books. t the end o f 1935,20th detective, and Chan was A Century-Fox bought the studio’s most popular the film rights to Thank “star” after Shirley Ton, Jeeves (along with a Temple. one-year option on the Like Chan, Jeeves had other stories) and the right been brought to the no to make other films cen tice of the American read tered around Jeeves. Look ing public in The Saturday ing for potentially pro Evening Post. The Jeeves lific—and profitable — film series seems to have properties, the studio was been launched on what interested in any character was perceived as a sure who seemed to have the bet, casting Arthur potential to lure filmgoers Treacher, known for play to film after film, no less ing butler roles, as the fa than a modern television mous literary butler. series. Earlier in the year, However, while the Chan Fox’s merger with 20th series was cast and pre Century had enhanced the sented in a manner conso A studio photo of the three principals in the first Jeeves film: studio’s status, and a CCB” nant with Biggers’s liter David Niven, Virginia Field, and Arthur Treacher. unit was organized under ary creation, the Jeeves Sol Wurtzel, who had a $6,000,000 annual budget for films revealed no sense of the situations and character pat 24 “Bs” per year. -

Wodehouse and the Baroque*1

Connotations Vol. 20.2-3 (2010/2011) Worcestershirewards: Wodehouse and the Baroque*1 LAWRENCE DUGAN I should define as baroque that style which deli- berately exhausts (or tries to exhaust) all its pos- sibilities and which borders on its own parody. (Jorge Luis Borges, The Universal History of Infamy 11) Unfortunately, however, if there was one thing circumstances weren’t, it was different from what they were, and there was no suspicion of a song on the lips. The more I thought of what lay before me at these bally Towers, the bowed- downer did the heart become. (P. G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters 31) A good way to understand the achievement of P. G. Wodehouse is to look closely at the style in which he wrote his Jeeves and Wooster novels, which began in the 1920s, and to realise how different it is from that used in the dozens of other books he wrote, some of them as much admired as the famous master-and-servant stories. Indeed, those other novels and stories, including the Psmith books of the 1910s and the later Blandings Castle series, are useful in showing just how distinct a style it is. It is a unique, vernacular, contorted, slangy idiom which I have labeled baroque because it is in such sharp con- trast to the almost bland classical sentences of the other Wodehouse books. The Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary describes the ba- roque style as “marked generally by use of complex forms, bold or- *For debates inspired by this article, please check the Connotations website at <http://www.connotations.de/debdugan02023.htm>. -

Psmith in Pseattle: the 18Th International TWS Convention It’S Going to Be Psensational!

The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 35 Number 4 Winter 2014 Psmith in Pseattle: The 18th International TWS Convention It’s going to be Psensational! he 18th biennial TWS convention is night charge for a third person, but Tless than a year away! That means there children under eighteen are free. are a lot of things for you to think about. Reservations must be made before While some of you avoid such strenuous October 8, 2015. We feel obligated activity, we will endeavor to give you the to point out that these are excellent information you need to make thinking as rates both for this particular hotel painless as possible. Perhaps, before going and Seattle hotels in general. The on, you should take a moment to pour a stiff special convention rate is available one. We’ll wait . for people arriving as early as First, clear the dates on your calendar: Monday, October 26, and staying Friday, October 30, through Sunday, through Wednesday, November 4. November 1, 2015. Of course, feel free to Third, peruse, fill out, and send come a few days early or stay a few days in the registration form (with the later. Anglers’ Rest (the hosting TWS chapter) does appropriate oof), which is conveniently provided with have a few activities planned on the preceding Thursday, this edition of Plum Lines. Of course, this will require November 29, for those who arrive early. There are more thought. Pour another stiff one. You will have to many things you will want to see and do in Seattle. -

Index to Wooster Sauceand by The

Index to Wooster Sauce and By The Way 1997–2020 Guide to this Index This index covers all issues of Wooster Sauce and By The Way published since The P G Wodehouse Society (UK) was founded in 1997. It does not include the special supplements that were produced as Christmas bonuses for renewing members of the Society. (These were the Kid Brady Stories (seven instalments), The Swoop (seven instalments), and the original ending of Leave It to Psmith.) It is a very general index, in that it covers authors and subjects of published articles, but not details of article contents. (For example, the author Will Cuppy (a contemporary of PGW’s) is mentioned in several articles but is only included in the index when an article is specifically about him.) The index is divided into three sections: I. Wooster Sauce and By The Way Subject Index Page 1 II. Wooster Sauce and By The Way Author Index Page 34 III. By The Way Issues in Number Order Page 52 In the two indexes, the subject or author (given in bold print) is followed by the title of the article; then, in bold, either the issue and page number, separated by a dash (for Wooster Sauce); or ‘BTW’ and its issue number, again separated by a dash. For example, 1-1 is Wooster Sauce issue 1, page 1; 20-12 is issue 20, page 12; BTW-5 is By The Way issue 5; and so on. See the table on the next page for the dates of each Wooster Sauce issue number, as well as any special supplements. -

By Jeeves a Diversionary Entertainment

P lum Lines The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Vol. 17 N o 2 S u m m er 1996 I h i l l I f \ i\ ilSI | PAUL SARGFNT ,„ 1hc highly unlikely even, of the euneelton of ,o„igh,'« f t * . C»>eer, l,y Mr. Wooster, the following emergency entertainment m . performed in its stead. By Jeeves a diversionary entertainment A review by Tony Ring Wodehouse, with some excellent and vibrant songs, also eminently suitable for a life with rep, amateur and school The Special Notice above, copied from the theater program, companies. indicates just how fluffy this ‘Almost Entirely New Musical’ is. First, the theatre. It seats just over 400 in four banks of Many members have sent reviews and comments about this seats, between which the aisles are productively used for popular musical and I can’t begin to print them all. My apolo the introduction o f the deliberately home-made props, gies to all contributors not mentioned here.—OM such as Bertie Wooster’s car, crafted principally out of a sofa and cardboard boxes. Backstage staff are used to h e choice o f B y Jeeves to open the new Stephen bring some o f the props to life, such as the verges on the Joseph Theatre in Scarborough has given us the edge o f the road, replete with hedgehogs, and die com T opportunity to see what can be done by the combinationpany cow has evidently not been struck down with BSE. o f a great popular composer, a top playwright, some ideas The production is well suited to this size o f theatre: it and dialogue from the century’s greatest humorist, a would not sit easily in one of the more spectacular auditoria talented and competent cast, and a friendly new theatre in frequently used for Lloyd Webber productions. -

Subversive Shakespearean Intertextualities in PG

Sarah Säckel What’s in a Wodehouse? (Non-) Subversive Shakespearean Intertextualities in P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster Novels P.G. Wodehouse’s use of intertextual references in his popular comic novels achieves several effects. Most quotations from canonised texts create incongruous, humorous dialogues and scenes. Frequent repetitions of the same quoted material turn it into a part of the ‘Wooster world’, achieve a certain ‘monologic closedness’ and heighten the effect of readerly immersion. On the other hand, the intertexts also open up the novels to an intertextual dialogue which trig- gers comparative readings. The usage of mainly English intertexts, however, creates a ‘monocul- tural’ dialogue which emphasises the texts’ portrayal of ‘Englishness’ and ‘English humour’. The intertextual references thus work as pillars of English cultural memory; pillars on which the Jeeves and Wooster novels’ reception itself is built. This paper shall concentrate on the predomi- nating intertextual dialogue between P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster novels and a selec- tion of William Shakespeare’s plays. Introduction and Theoretical Approach What’s in a Wodehouse? – Shakespeare and much more. Various forms of intertextual reference such as allusion, imitation, rewriting, parody and quo- tation abound in P.G. Wodehouse’s comic Jeeves and Wooster1 novels. Pos- sibly one of the most quoted sentences in secondary texts concerned with the analysis of P.G. Wodehouse’s comic novels is the following statement in which the author describes his style: I believe there are two ways of writing novels. One is mine, making a sort of musical comedy without music and ignoring real life altogether; the other is going right deep down into life and not caring a damn.2 1 None of the novels is actually called Jeeves and Wooster.