Athena/Athens on Stage: Athena in the Tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

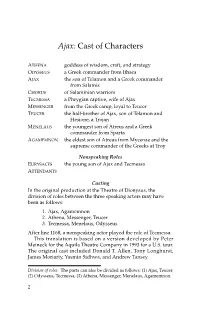

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

Democritus C

Democritus c. 460 BC-c. 370 BC (Also known as Democritus of Abdera) Greek philosopher. home to the philosopher Protagoras. There are several indications, both external and internal to his writings, The following entry provides criticism of Democritus’s that Democritus may have held office in Abdera and life and works. For additional information about Democ- that he was a wealthy and respected citizen. It is also ritus, see CMLC, Volume 47. known that he traveled widely in the ancient world, visit- ing not only Athens but Egypt, Persia, the Red Sea, pos- sibly Ethiopia, and even India. Scholars also agree that he INTRODUCTION lived a very long life of between 90 and 109 years. Democritus of Abdera, a contemporary of Socrates, stands Democritus is said to have been a pupil of Leucippus, an out among early Greek philosophers because he offered important figure in the early history of philosophy about both a comprehensive physical account of the universe and whom little is known. Aristotle and others credit Leucippus anaturalisticaccountofhumanhistoryandculture. with devising the theory of atomism, and it is commonly Although none of his works has survived in its entirety, believed that Democritus expanded the theory under his descriptions of his views and many direct quotations from tutelage. However, some scholars have suggested that his writings were preserved by later sources, beginning Leucippus was not an actual person but merely a character with the works of Aristotle and extending to the fifth- in a dialogue written by Democritus that was subsequently century AD Florigelium (Anthology) of Joannes Stobaeus. lost. A similar strategy was employed by the philosopher While Plato ignored Democritus’s work, largely because he Parmenides, who used the character of a goddess to elu- disagreed with his teachings, Aristotle acknowledged De- cidate his views in his didactic poem, On Nature. -

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia

Urban Planning in the Greek Colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia (8th – 6th centuries BCE) An honors thesis for the Department of Classics Olivia E. Hayden Tufts University, 2013 Abstract: Although ancient Greeks were traversing the western Mediterranean as early as the Mycenaean Period, the end of the “Dark Age” saw a surge of Greek colonial activity throughout the Mediterranean. Contemporary cities of the Greek homeland were in the process of growing from small, irregularly planned settlements into organized urban spaces. By contrast, the colonies founded overseas in the 8th and 6th centuries BCE lacked any pre-existing structures or spatial organization, allowing the inhabitants to closely approximate their conceptual ideals. For this reason the Greek colonies in Sicily and Magna Graecia, known for their extensive use of gridded urban planning, exemplified the overarching trajectory of urban planning in this period. Over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BCE the Greek cities in Sicily and Magna Graecia developed many common features, including the zoning of domestic, religious, and political space and the implementation of a gridded street plan in the domestic sector. Each city, however, had its own peculiarities and experimental design elements. I will argue that the interplay between standardization and idiosyncrasy in each city developed as a result of vying for recognition within this tight-knit network of affluent Sicilian and South Italian cities. This competition both stimulated the widespread adoption of popular ideas and encouraged the continuous initiation of new trends. ii Table of Contents: Abstract. …………………….………………………………………………………………….... ii Table of Contents …………………………………….………………………………….…….... iii 1. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………..……….. 1 2. -

The Fleet of Syracuse (480-413 BCE)

ANDREAS MORAKIS The Fleet of Syracuse (480-413 BCE) The Deinomenids The ancient sources make no reference to the fleet of Syracuse until the be- ginning of the 5th century BCE. In particular, Thucydides, when considering the Greek maritime powers at the time of the rise of the Athenian empire, includes among them the tyrants of Sicily1. Other sources refer more precisely to Gelon’s fleet, during the Carthaginian invasion in Sicily. Herodotus, when the Greeks en- voys asked for Gelon’s help to face Xerxes’ attack, mentions the lord of Syracuse promising to provide, amongst other things, 200 triremes in return of the com- mand of the Greek forces2. The same number of ships is also mentioned by Ti- maeus3 and Ephorus4. It is very odd, though, that we hear nothing of this fleet during the Carthaginian campaign and the Battle of Himera in either the narration of Diodorus, or the briefer one of Herodotus5. Nevertheless, other sources imply some kind of naval fighting in Himera. Pausanias saw offerings from Gelon and the Syracusans taken from the Phoenicians in either a sea or a land battle6. In addition, the Scholiast to the first Pythian of Pindar, in two different situations – the second one being from Ephorus – says that Gelon destroyed the Carthaginians in a sea battle when they attacked Sicily7. 1 Thuc. I 14, 2: ὀλίγον τε πρὸ τῶν Μηδικῶν καὶ τοῦ ∆αρείου θανάτου … τριήρεις περί τε Σικελίαν τοῖς τυράννοις ἐς πλῆθος ἐγένοντο καὶ Κερκυραίοις. 2 Hdt. VII 158. 3 Timae. FGrHist 566 F94= Polyb. XII 26b, 1-5, but the set is not the court of Gelon, but the conference of the mainland Greeks in Corinth. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Gillian Bevan Is an Actor Who Has Played a Wide Variety of Roles in West End and Regional Theatre

Gillian Bevan is an actor who has played a wide variety of roles in West End and regional theatre. Among these roles, she was Dorothy in the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of The Wizard of Oz, Mrs Wilkinson, the dance teacher, in the West End production of Billy Elliot, and Mrs Lovett in the West Yorkshire Playhouse production of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Gillian has regularly played roles in other Sondheim productions, including Follies, Merrily We Roll Along and Road Show, and she sang at the 80th birthday tribute concert of Company for Stephen Sondheim (Donmar Warehouse). Gillian spent three years with Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, and her Shakespearian roles include Polonius (Polonia) in the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre production of Hamlet (Autumn, 2014) with Maxine Peake in the title role. Gillian’s many television credits have included Teachers (Channel 4) in which she played Clare Hunter, the Headmistress, and Holby City (BBC1) in which she gave an acclaimed performance as Gina Hope, a sufferer from Motor Neurone Disease, who ends her own life in an assisted suicide clinic. During the early part of 2014, Gillian completed filming London Road, directed by Rufus Norris, the new Artistic Director of the National Theatre. In the summer of 2014 Gillian played the role of Hera, the Queen of the Gods, in The Last Days of Troy by the poet and playwright Simon Armitage. The play, a re-working of The Iliad, had its world premiere at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre and then transferred to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, London. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Attic Inscriptions Online Website

Attic Inscriptions: Education Teachers’ Notes on OCR A-LEVEL ANCIENT HISTORY Attic Inscriptions for the Greece Period Study These notes offer introductory commentaries on ancient Athenian inscriptions relevant to the Greece Period Study, ‘Relations between Greek states and between Greek and non-Greek states, 492–404 BC’. They are aimed at teachers in the hope that they provide guidance on the relevance of ancient Athenian inscriptions to the specification and also some insight into the application and analysis of inscriptions as sources for ancient Greek history. We focus on eight selected inscriptions. Three are prescribed sources for the specification, while five are non-prescribed. The non-prescribed sources allow teachers to widen their students’ knowledge; moreover, it should be remembered that candidates can be credited equally for using prescribed and non-prescribed sources in their answers, and we feel that these five sources offer a great deal for teachers and students to work with. The notes were written by Peter Liddel and James Renshaw, drawing upon the translations and commentaries of S.D. Lambert and others on the Attic Inscriptions Online website. We welcome comments on this material or ideas for their expansion: [email protected] Prescribed Sources: 1. Athenian Tribute List (454/3) 2. Athenian relations with Chalkis (446/5 (or 424/3?) 3. Decrees about reassessment of Tribute (Thoudippos’ decrees) (425/4) Non-Prescribed sources: 4. Memorial of Athenian war dead (460-59) 5. Regulations for Erythrai (454-450) 6. Foundation of colony at Brea (c. 440-432) 7. Financial decrees (Kallias’ decrees) (434/3?) 8. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015)

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 31 | 2018 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015) Angelos Chaniotis Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/2741 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.2741 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2018 Number of pages: 167-219 ISBN: 978-2-87562-055-2 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, “Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015)”, Kernos [Online], 31 | 2018, Online since 01 October 2020, connection on 25 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/2741 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/kernos.2741 This text was automatically generated on 25 January 2021. Kernos Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015) 1 Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 2015 (EBGR 2015) Angelos Chaniotis To the memory of David Jordan 1 The 28th issue of the EBGR presents epigraphic corpora and new epigraphic finds published in 2015. I have only included a few contributions to the reading and interpretation of old finds as well as a small selection of publications that adduce inscriptions for the study of religious phenomena. I have also summarizes some publications of earlier years that had not been included in earlier issues of the EBGR (2007–2013). 2 In this issue, I summarize the content of new corpora from Athens (34), Macedonia (56. 109), Termessos (64), and Hadrianopolis (79) that mainly contain dedications, but also records of manumission through dedication to deities (56). The two most important new inscriptions are the incantations from Selinous (?), known as the ‘Getty hexameters’ and a cult regulation from Thessaly. -

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed As the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon

The Parthenon Frieze: Viewed as the Panathenaic Festival Preceding the Battle of Marathon By Brian A. Sprague Senior Seminar: HST 499 Professor Bau-Hwa Hsieh Western Oregon University Thursday, June 07, 2007 Readers Professor Benedict Lowe Professor Narasingha Sil Copyright © Brian A. Sprague 2007 The Parthenon frieze has been the subject of many debates and the interpretation of it leads to a number of problems: what was the subject of the frieze? What would the frieze have meant to the Athenian audience? The Parthenon scenes have been identified in many different ways: a representation of the Panathenaic festival, a mythical or historical event, or an assertion of Athenian ideology. This paper will examine the Parthenon Frieze in relation to the metopes, pediments, and statues in order to prove the validity of the suggestion that it depicts the Panathenaic festival just preceding the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The main problems with this topic are that there are no primary sources that document what the Frieze was supposed to mean. The scenes are not specific to any one type of procession. The argument against a Panathenaic festival is that there are soldiers and chariots represented. Possibly that biggest problem with interpreting the Frieze is that part of it is missing and it could be that the piece that is missing ties everything together. The Parthenon may have been the only ancient Greek temple with an exterior sculpture that depicts any kind of religious ritual or service. Because the theme of the frieze is unique we can not turn towards other relief sculpture to help us understand it. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt .....................................................................