Manipulation Under Anesthesiaco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distinguished Lecture

Past Present and Future of Joint Manipulation Stanley V. Paris PT., PhD, FAPTA N.Z.S.P., F.N.Z.S.P.(Hon Fellow & Life).,, N.Z.M.T.A.,(Hon Life)., I.F.O.M.P.T.,(Hon Life)., F.A.A.O.M.P.T., M.C.S.P., B.I.M. Abstract: Presented as the first Distinguished Lecturers Award, of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manipulative Physical Therapists October 2011, the paper begins by addressing the richness of manipulative experience that caused the Founding Fellows to create the Academy. Speaking to his concerns that this richness seems to be forgotten by many practitioners he reviewed also the known effects of manipulation before then evaluating the evidence based literature criticizing much of it for being too basic and taking the profession back to where we were some fifty years ago before specific manipulative techniques were in vogue. Thus the current research is largely on non- specific regional techniques done for effect rather than for pathoanatomical and mechanical consideration. Many of the techniques being studied and promoted as manipulations ion the current literature do not justify to be called “manipulations” lacking as they do “skilled passive movements to a joint.” The paper argues for remembering that published literature is only one leg of the three legged stool of evidenced based practice, the other legs being patients wishes and culture, and the third being individual therapists expertise. Given the quality of much current physical therapy evidenced based literature Dr. Paris did not think that it was of sufficient scope and quality on which to base our practice. -

Effectiveness of the Muscle Energy Technique Versus Osteopathic

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Effectiveness of the Muscle Energy Technique versus Osteopathic Manipulation in the Treatment of Sacroiliac Joint Dysfunction in Athletes Urko José García-Peñalver 1, María Victoria Palop-Montoro 1 and David Manzano-Sánchez 2,* 1 Facultad de Fisioterapia, Universidad Católica de San Antonio (UCAM), Av. de los Jerónimos, 135, 30107 Murcia, Spain; [email protected] (U.J.G.-P.); [email protected] (M.V.P.-M.) 2 Facultad de Ciencias del Deporte, Universidad de Murcia, Calle Argentina, 19, 30720 San Javier, Murcia, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-693-35-33-97 Received: 21 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 22 June 2020 Abstract: Background: The study of injuries stemming from sacroiliac dysfunction in athletes has been discussed in many papers. However, the treatment of this issue through thrust and muscle-energy techniques has hardly been researched. The objective of our research is to compare the effectiveness of thrust technique to that of energy muscle techniques in the resolution of sacroiliac joint blockage or dysfunction in middle-distance running athletes. Methods: A quasi-experimental design with three measures in time (pre-intervention, intervention 1, final intervention after one month from the first intervention) was made. The sample consisted of 60 adult athletes from an Athletic club, who were dealing with sacroiliac joint dysfunction. The sample was randomly divided into three groups of 20 participants (43 men and 17 women). One intervention group was treated with the thrust technique, another intervention group was treated with the muscle–energy technique, and the control group received treatment by means of a simulated technique. -

Mechanisms Involved in the Sounds Produced by Manipulation in Synovial Joints: Possible Role of Ph Changes in Lessening Pain Levels

MECHANISMS INVOLVED IN THE SOUNDS PRODUCED BY MANIPULATION IN SYNOVIAL JOINTS: POSSIBLE ROLE OF PH CHANGES IN LESSENING PAIN LEVELS Yulia S. Suvorova, PhD1, Ronald Conger, DC1 1Muscle-Joint Center Netherland, Bredalaan 75, 5652 JB Eindhoven, Netherlands Email address: [email protected] PH Changes Suvarova and Conger MECHANISMS INVOLVED IN THE SOUNDS PRODUCED BY MANIPULATION IN SYNOVIAL JOINTS: POSSIBLE ROLE OF PH CHANGES IN LESSENING PAIN LEVELS ABSTRACT The exact mechanisms involved in the sounds produced by manipulation of synovial Joints have not been unequivocally elucidated but a number of explanations have been put forward. We have reviewed experiments designed to explain these sounds, with results that were quite unexpected. We have also considered the composition of synovial fluid and how its pH may potentially change locally after the release of CO2 by physical manipulation. The insights gained provide a rational explanation for the sounds generated by Joint manipulation and the beneficial effects of manipulation on patients with Joint disorders and pain. We recommend that Joint manipulation should be prescribed as first-line therapy before drug therapy and expensive surgery is considered. (Chiropr J Australia 2017;45:203-216) Key Indexing Terms: Cavitation; Chiropractic; Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment; Synovial Joints INTRODUCTION Many people notice that when they move their Joints, particularly after a period of inactivity, they hear pops and cracks. In fact, most people experience this phenomenon – especially in their fingers, neck and knees. Usually Joint cracking and popping requires no treatment. However, if the cracking and popping in the Joints is accompanied by swelling and pain, a licensed health care professional should evaluate the patient. -

The Manipulation Education Manual

Manipulation Education Manual For Physical Therapist Professional Degree Programs Manipulation Education Committee APTA Manipulation Task Force Jointly sponsored by: Education Section and Orthopaedic Section, American Physical Therapy Association American Physical Therapy Association American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists 2004 April 2004 Dear Physical Therapist Educator, As you know, the practice of physical therapy has been under attack on many fronts recently; one of the most aggressive has been directed toward the physical therapist’s ability to provide manual therapy interventions including nonthrust and thrust mobilization/manipulations. APTA has been working with the American Academy of Orthopaedic Manual Physical Therapists (AAOMPT) and the Education and Orthopaedic Sections of APTA, to develop proactive initiatives to combat these attacks. In early 2003, strategies were developed to heighten awareness among academic and clinical faculty of legislative and regulatory threats to physical therapist use of manipulation in practice and in academic instruction. One of these strategies is to promote dialogue and resource sharing among physical therapy faculty regarding instruction, legislation, and regulation in the area of thrust manipulation. The Manipulation Education Manual (MEM) was developed to support the ongoing efforts in physical therapist education programs to provide appropriate, evidence-based instruction in thrust manipulation. Educational preparation of physical therapists for the practice of manipulative -

Alteration in Corticospinal Excitability, Talocrural Joint Range of Motion, and Lower Extremity Function Following Manipulation in Non-Disabled Individuals

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons School of Pharmacy Faculty Articles Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy 4-1-2013 Alteration in corticospinal excitability, talocrural joint range of motion, and lower extremity function following manipulation in non-disabled individuals Todd E. Davenport University of the Pacific, [email protected] Stephen F. Reischl University of Southern California Somporn Sungkarat Chiang Mai University Jason Cozby University of Southern Claifornia Lisa Meyer University of Southern California See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/phs-facarticles Part of the Orthopedics Commons Recommended Citation Davenport TE, Reischl SF, Sungkarat S, Cozby J, Meyer L, Fisher BE. Alteration in corticospinal excitability, talocrural joint range of motion, and lower extremity function following manipulation in non-disabled individuals. Orthopaedic Physical Therapy Practice. 2013;25(2):97-102. © 2013, Orthopaedic Section, APTA, Inc. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Thomas J. Long School of Pharmacy at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Pharmacy Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Todd E. Davenport, Stephen F. Reischl, Somporn Sungkarat, Jason Cozby, Lisa Meyer, and Beth E. Fisher This article is available at Scholarly Commons: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/phs-facarticles/136 Alteration in Corticospinal Excitability, Todd E. Davenport, PT, DPT, OCSI Stephen E Reischl, PT, DPT, ocs2 Talocrural Joint Range of Motion, and Somporn Sungkarat, PT, PhD3 Lower Extremity Function Following Jason CozbJG PT, DPT, OCS2 Lisa Meyer, PT, OPT, OCS4 Manipulation in Non-disabled Individuals Beth E. -

A History of Manipulative Therapy

A History of Manipulative Therapy Erland Pettman, PT, MCSP, MCPA, FCAMT, COMT Abstract: Manipulative therapy has known a parallel development throughout many parts of the world. The earliest historical reference to the practice of manipulative therapy in Europe dates back to 400 BCE. Over the centuries, manipulative interventions have fallen in and out of favor with the medical profession. Manipulative therapy also was initially the mainstay of the two leading alternative health care systems, osteopathy and chiropractic, both founded in the latter part of the 19th century in response to shortcomings in allopathic medicine. With medical and osteopathic physicians initially instrumen- tal in introducing manipulative therapy to the profession of physical therapy, physical therapists have since then provided strong contributions to the fi eld, thereby solidifying the profession’s claim to have manipulative therapy within in its legally regulated scope of practice. Key Words: Manipulative Therapy, Physical Therapy, Chiropractic, Osteopathy, Medicine, History istorically, manipulation can trace its origins from tail in which this is described suggests that the practice of parallel developments in many parts of the world manipulation was well established and predated the 400 BCE Hwhere it was used to treat a variety of musculoskele- reference11. tal conditions, including spinal disorders1. It is acknowl- In his books on joints, Hippocrates (460–385 BCE), who edged that spinal manipulation is and was widely practised in is often referred to as the father of medicine, was the fi rst many cultures and often in remote world communities such physician to describe spinal manipulative techniques using as by the Balinese2 of Indonesia, the Lomi-Lomi of Hawaii3-5, gravity, for the treatment of scoliosis. -

Spinal Manipulation • S

12/30/2019 Disclosure Spinal Manipulation • S. Jake Thompson – No relevant financial relationship exists. S. Jake Thompson MPT, ATC, SCS Cert. SMT, Cert DN, Dip. Osteopractic, AAOMPT Fellow In Training 1 2 Presentation Objectives • Be cognizant of safety issues regarding spinal manipulation. • Recognize the current best evidence for the implementation of spinal manipulation in clinical practice 3 4 SPINAL MANIPULATION SPINAL MANIPULATION • Guide to PT Practice- •PROS Mobilization/Manipulation = “A manual therapy technique •Non pharm comprised of a continuum of skilled passive movements to •Non surgical joints and/or related soft tissues that are applied at varying speeds and amplitudes, including a small amplitude/high •Cost effective compared to exercise (UK BEAM 2002) velocity therapeutic movement” •Safe (Oliphant 2004) • Manipulation Education Committee, June 2003- •Current research is as strong as any other Thrust Joint Manipulation (TJM)- high velocity, low intervention (PT) amplitude therapeutic movements within or at end range of motion. 5 6 1 12/30/2019 SPINAL MANIPULATION SPINAL MANIPULATION •Cons • Placebo • Western Medicine perception • Alternative Medicine • Poor face validity “out of alignment” and “subluxation theory” • Lack of an identifiable mechanism of action for MT may limit the acceptability of these techniques • Viewed as less scientific Dekanich,J., Pitcher, M., Steadman Hawkins Sports Medicine Lecture Series: Chiropractic (2006) 7 8 History of Manipulation History of Manipulation • Hippocrates, Father of • Wharton -

Orthopedic Manual Therapy for the Pediatric Patient

Orthopedic Manual Therapy for the Pediatric Patient Mitchell Selhorst, DPT, OCS Nationwide Children’s Hospital Sports and Orthopedic PT Columbus, Ohio ………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Learning Objectives The attendee will: • Understand the specific precautions and the relative risk of performing orthopedic manual therapy on pediatric patients. • Identify pediatric patients who are appropriate for orthopedic manual therapy. • Use orthopedic manual physical therapy to minimize pain and maximize function in pediatric orthopedic patients. ………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Pediatric Physical Therapy ………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. This is the Pediatric I Mean Kids Need PT Too! Pediatric Pain is Not Benign • Injury in childhood may lead to increased risk of pain in adulthood.23 • Pain does not go away on its own – 2/3 of adolescents with low back pain will have chronic or recurrent symptoms 6 months later.38 Clinical Practice Guidelines Recommend use of Manual Therapy Alright, Let’s Do Manual Therapy! Wait… Growing Children ………………..…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Contraindications and Precautions • Contraindication: A circumstance which absolutely rules out the use of a therapeutic method which would otherwise be indicated. • Precaution: The risks of a treatment have to be carefully assessed before treatment is initiated, and it can only be administered if its benefits to the patient are greater than its risks ………………..……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

PDF | Updated 5-22-21

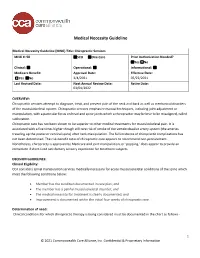

Medical Necessity Guideline Medical Necessity Guideline (MNG) Title: Chiropractic Services MNG #: 50 ☒SCO ☒One Care Prior Authorization Needed? ☒Yes ☐No Clinical: ☒ Operational: ☒ Informational: ☒ Medicare Benefit: Approval Date: Effective Date: ☐ Yes ☒No 3/4/2021 05/22/2021 Last Revised Date: Next Annual Review Date: Retire Date: 03/04/2022 OVERVIEW: Chiropractic services attempt to diagnose, treat, and prevent pain of the neck and back as well as mechanical disorders of the musculoskeletal system. Chiropractic services emphasize manual techniques, including joint adjustment or manipulation, with a particular focus on head and spine joints which a chiropractor may believe to be misaligned, called subluxation. Chiropractic care has not been shown to be superior to other medical treatments for musculoskeletal pain. It is associated with a five times higher though still rare risk of stroke of the vertebrobasilar artery system (the arteries traveling up the posterior cervical spine) after neck manipulation. The full incidence of chiropractic complications has not been determined. The risk-benefit ratio of chiropractic care appears to recommend non-procurement. Nonetheless, chiropracty is approved by Medicare and joint manipulation, or ‘popping,’ does appear to provide an immediate if short-lived satisfactory sensory experience for treatment subjects. DECISION GUIDELINES: Clinical Eligibility: CCA considers spinal manipulation services medically necessary for acute musculoskeletal conditions of the spine which meet the following conditions below: • Member has the condition documented in care plan; and • The member has a painful musculoskeletal disorder; and • The medical necessity for treatment is clearly documented; and • Improvement is documented within the initial four weeks of chiropractic care. Determination of need: Clinical conditions for which chiropractic therapy is being considered must be documented in the chart as follows - 1 © 2021 Commonwealth Care Alliance, Inc. -

APG Regulations

FINAL as of 8/22/08 Pursuant to the authority vested in the Commissioner of Health by Section 2807(2-a) of the Public Health Law, Part 86 of Title 10 of the Official Compilation of Codes, Rules and Regulations of the State of New York, is amended by adding a new Subpart 86-8, to be effective upon filing with the Secretary of State, to read as follows: SUBPART 86-8 OUTPATIENT SERVICES: AMBULATORY PATIENT GROUP (Statutory authority: Public Health Law § 2807(2-a)(e)) Sec. 86-8.1 Scope 86-8.2 Definitions 86-8.3 Record keeping, reports and audits 86-8.4 Capital reimbursement 86-8.5 Administrative rate appeals 86-8.6 Rates for new facilities during the transition period 86-8.7 APGs and relative weights 86-8.8 Base rates 86-8.9 Diagnostic coding and rate computation 86-8.10 Exclusions from payment 86-8.11 System updating 86-8.12 Payments for extended hours of operation § 86-8.1 Scope (a) This Subpart shall govern Medicaid rates of payments for ambulatory care services provided in the following categories of facilities for the following periods: (1) outpatient services provided by general hospitals on and after December 1, 2008; (2) emergency department services provided by general hospitals on and after January 1, 2009; (3) ambulatory surgery services provided by general hospitals on and after December 1, 2008; (4) ambulatory services provided by diagnostic and treatment centers on and after March 1, 2009; and (5) ambulatory surgery services provided by free-standing ambulatory surgery centers on and after March 1, 2009. -

Orthopedic Coding in Ascs

presents… Orthopedic Coding in ASCs 90-minute audio conference June 11, 2008 2:00 p.m.–3:30 p.m. (Eastern) 1:00 p.m.–2:30 p.m. (Central) 12:00 p.m.–1:30 p.m. (Mountain) 11:00 a.m.–12:30 p.m. (Pacific) The Orthopedic Coding in ASCs audio conference materials package is provided by ASC Communications, 315 Vernon Ave, Glencoe, IL 60022. Copyright 2008, ASC Communications. Attendance at the audio conference is restricted to employees, consultants and members of the medical staff of the attendee. The audio conference materials are intended solely for use in conjunction with the associated ASC Communications audio conference. You may make copies of these materials for your internal use by attendees of the audio conference only. All such copies must bear this message. Dissemination of any information in these materials or the audio conference to any party other than the attendee or its employees is strictly prohibited. Advice given is general, and attendees and readers of the materials should consult professional counsel for specific legal, ethical or clinical questions. For more information, contact ASC Communications 315 Vernon Ave, Glencoe, IL 60022 Phone: (800) 417-2035 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.beckersasc.com 2 Welcome! We are pleased that you have chosen to set aside a part of your day and join us for our Orthopedic Coding in ASCs audio conference featuring Stephanie Ellis. We are sure you will find the conference educational and worth your time, and we encourage you to take advantage of the opportunity to ask our experts your questions during the audio conference. -

Mechanism of Action of Spinal Manipulative Therapy

Joint Bone Spine 70 (2003) 336–341 www.elsevier.com/locate/bonsoi Review Mechanism of action of spinal manipulative therapy Jean-Yves Maigne a,*, Philippe Vautravers b a Physical Medicine Department, Hôtel-Dieu Teaching Hospital, Place du Parvis de Notre-Dame, 75004 Paris, France b Physical Medicine Department, Hautepierre Teaching Hospital, Strasbourg, France Received 9 April 2002; accepted 15 November 2002 Abstract Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) acts on the various components of the vertebral motion segment. SMT distracts the facet joints, with faster separation when a cracking sound is heard. Intradiscal pressure may decrease briefly. Forceful stretching of the paraspinal muscles occurs, which induces relaxation via mechanisms that remain to be fully elucidated. Finally, SMT probably has an inherent analgesic effect independent from effects on the spinal lesion. These changes induced by SMT are beneficial in the treatment of spinal pain but short-lived. To explain a long-term therapeutic effect, one must postulate a reflex mechanism, for instance the disruption of a pain–spasm–pain cycle or improvement of a specific manipulation-sensitive lesion, whose existence has not been established to date. © 2003 Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS. All rights reserved. Keywords: Spinal manipulative therapy; Low back pain; Manual medicine; Chiropractics; Osteopathy 1. Introduction vertebral motion segment. The conclusions call into question a number of widely held beliefs about SMT. Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) has been proved ef- fective in alleviating acute low back pain and may help to improve neck pain, sciatica, and chronic low back pain [1,2]. 2. Effects on the vertebral motion segment The definition of SMT is not agreed on and varies across specialties (osteopathy, chiropractic, and medicine).