History Tour North – South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plaquette CMPP Rue D'auxonne 2020 (1).Pdf

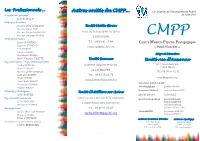

Les Professionnels … Autres unités du CMPP… Les Pupilles de l’Enseignement Public Assistante sociale de Côte-d'Or Isabelle ARGON ∵ Pédopsychiatres Docteur Quentin BARROIS Unité Motte Giron Docteur Simon BEAL Docteur Marie-Alix DORLET 9 rue du Fort de la Motte Giron Docteur Audrey PINGAUD 21000 DIJON CMPP Orthophonistes Lucie CAQUINEAU Tél. : 03 80 41 17 44 Centre Médico-Psycho-Pédagogique Ségolène FETIVEAU [email protected] « Paul Picardet » Alix PERRIER Laurène RAGON ∴ Siège et Direction Madeleine THOMAS Marie-Christine VALETTE Unité Beaune Unité rue d’Auxonne Psychologues - Psychothérapeutes Cécilia BUTTARD 8 avenue Guigone de Salins 67 C rue d'Auxonne 21000 DIJON Flavie CHOLLET 21200 BEAUNE Marie-Isabelle GONZALEZ Tél. : 03 80 66 42 41 Anthony LAURENT Tél. : 03 80 25 02 73 Elodie LEPINE [email protected] [email protected] Anne-Marie NOIROT Directeur Administratif Françoise RAINERO ∵ et Pédagogique Gisèle IVANOFF Virginie MAZUR Directeur Médical Docteur Simon BEAL Neuropsychologue Unité Châtillon-sur-Seine Gaëlle ROUVIER Chef de service Rachel JOLY Psychomotriciennes Centre social, 2 Ter rue de la Libération Secrétariat médical Annick BILLARD Céline BARRAUX 21400 CHATILLON-SUR-SEINE Fanny JASSERME Bérengère HEBERT Catherine MAYOL Catherine TILLEROT Enseignants Tél. : 03 80 91 26 48 Sarah PHILIPPON-MASSON Comptabilité Véronique GARROT [email protected] Sophie SCHMITT Florence PAVESI Damien VITTEAUX Antenne Fontaine d’Ouche Antenne Quetigny Enseignant coordonnateur 20 avenue du Lac 3 bd des Herbues 21000 DIJON Frédéric BERNARDIN 21800 QUETIGNY Tél. : 03 80 41 47 34 Tél. : 03 80 46 88 70 ∴ Créés depuis 1946, sous le double parrainage des Pour qui ? Au terme d'une évaluation pluridisciplinaire, différents traitements en individuel ou en groupe Ministères de la Santé et de l'Education Nationale, les ≻ Enfants et adolescents : de la maternelle au lycée, peuvent être proposés : CMPP sont des services de diagnostic et de soins à la jusqu'à 20 ans. -

Projet D'amenagement Et De Developpement Durables

REVISION prescrite par délibération du Comité syndical du 28 septembre 2016 PROJET arrêté par délibération du Comité syndical du 28 novembre 2018 ENQUETE PUBLIQUE prescrite par arrêté du 12 avril 2019 3- PROJET D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE DEVELOPPEMENT DURABLES (PADD) Schéma de cohérence territoriale du Dijonnais – Projet d’Aménagement et de Développement Durables 2 Sommaire I Le PADD dans le contexte législatif et de la révision du SCoT en vigueur p.4 1 Le PADD dans le processus du SCoT du Dijonnais p.5 2 Un PADD qui s’inscrit dans l’histoire du SCoT du Dijonnais p.6 II Des grands défis à la genèse du projet de territoire p.12 III Le positionnement stratégique p.16 La déclinaison du positionnement stratégique dans les objectifs de politiques d’aménagement et IV p.22 de programmation Axe 1 Organiser la diversité et les équilibres des espaces du SCoT du Dijonnais pour le compte de son attractivité p.24 Orientation 1 Affirmer une organisation urbaine polycentrique qui connecte les espaces métropolitains, périurbains et ruraux p.25 Orientation 2 Protéger, gérer et valoriser les ressources environnementales pour une plus grande durablité du territoire p.29 Orientation 3 Préserver et valoriser les espaces agricoles par la maîtrise de la consommation foncière p.32 Axe 2 Faire du cadre de vie un atout capital de l’attractivité du territoire p.33 Orientation 1 Faciliter le déploiement des mobilités pour une réduction des déplacements contraints et une meilleure qualité de l’air p.34 Fournir une liberté de choix par une offre de logements adaptée aux -

4 Bedroom Modern Villa for Sale – La Rochepot

Click to view MFH-BUR-MI4592V Several buildings from 16th century La Rochepot, Côte-d'Or, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté €549,000 inc. of agency fees 4 Beds 1 Baths 175 sqm 0.41 ha Several buildings from 16th century At a Glance Reference MFH-BUR-MI4592V Near to La Rochepot Price €549,000 Bed 4 Bath 1 Hab.Space 175 sqm Land 0.41 ha Pool No Land Tax N/A Property Description Former wine domain, with buildings on both side of courtyard, living accommodation and wine making areas. Situated on the high side of this hamlet known for its famous castle Rochepot. Ideal to be converted into tourism activity. Shops in nearby Nolay, and in Meursault. Beaune at 15 minutes. Total area to be developed is 650m2, split over several buildings. The main house, is accessed via the entrance porche and straight from the street. Downstairs, the grand salon, with wooden beams and grand burgundy fire place. The large dining room also has wooden beamed ceilings and stone walls. The small cosy living room also has a fire place. kitchen is simple but works, and then toilet. Access to the first floor is via a stone stair case. On this floor, 4 bedrooms, small room used as office and bathroom . At the other side of this street side building is another appartment, with salon, kitchen and three bedrooms. But this needs work. In the loft several rooms. On courtyard level the tasting room, which also has street access. ( to receive the clients) From here also access to the cellars and bottling room next door. -

Carte Des Itinéraires Cyclables En Côte D'or

MONTIGNY- SUR-AUBE CHÂTILLON- SUR-SEINE LAIGNES Liaison IS-SUR-TILLE CHÂTILLON-SUR-SEINE RECEY-SUR-OURCE Canal de Bourgogne IS-SUR-TILLE CHÂTILLON-SUR-SEINE GRANCEY-LE CHATEAU-NEUVELLE ROUGEMONT AIGNAY- LE-DUC MONTBARD Liaison IS-SUR-TILLE VAL-COURBE CHÂTILLON-SUR-SEINE BAIGNEUX- AIGNAY-LE-DUC LES-JUIFS Canal entre Champagne et Bourgogne Blagny-Courchamp Réalisé en 2011 23 VENAREY- IS-SUR-TILLE LES-LAUMES FONTAINE- Canal FRANCAISE de Bourgogne SEMUR-EN-AUXOIS Canal entre Champagne et Bourgogne PONT-DE-PANY ROUGEMONT SAINT-SEINE Réalisé en 2007 / 2008 L'ABBAYE Maxilly-Blagny Réalisé en 2010 103 15 DIJON MIREBEAU- Liaison VAL-SUZON SUR-BEZE VAUX-SUR-CRÔNE PRECY- Canal de Bourgogne Liaison Canal SOUS-THIL VITTEAUX 16 TALMAY de Bourgogne MORVAN VELARS- VELARS-SUR-OUCHE SUR-OUCHE PONT-DE-PANY DIJON Réalisé en 2004 VAUX-SUR- PONTAILLER- 17 CRÔNE SUR-SAÔNE PONT-DE-PANY CHENOVE LAMARCHE- SAULIEU POUILLY- DIJON SUR-SAÔNE EN-AUXOIS LA SAÔNE LAMARCHE-SUR-SAÔNE TALMAY-AUXONNE VAUX-SUR-CRÔNE Réalisé en 2007/2008 Réalisé en 2006 GEVREY- 36 Liaison Canal CHAMBERTIN 15 de Bourgogne ARNAY-LE-DUC OUGES AUXONNE SAINT-JEAN-DE-LOSNE AUXONNE - LIERNAIS DIJON-BEAUNE 23 SAINT-SYMPHORIEN 44 Réalisé en 2011 21 Liaison Canal de Bourgogne NUITS-SAINT-GEORGES VOIE BLEUE BEAUNE SAINT-JEAN ARNAY- DE-LOSNE LE-DUC Beaune- PREMEAUX-PRISSEY BLIGNY- SAINT- EUROVELO 6 SUR-OUCHE Premeaux-Prissey Réalisé en 2017 VOIE PAGNY SYMPHORIEN Vers Jura 21 DES VIGNES LE-CHÂTEAU SAVIGNY-LES-BEAUNE SAINT-SYMPHORIEN BEAUNE PAGNY-LA-VILLE TRAVAUX 2017 Réalisé en 2007 VOIE BLEUE EN SERVICE -

Domaine Regis Bouvier

DOMAINE REGIS BOUVIER Country: France Region: Burgundy Appellation(s): Bourgogne, Marsannay, Fixin, Morey-St-Denis, Gevrey-Chambertin Producer: Régis Bouvier Founded: 1981 Annual Production: 6,000 cases Farming: Lutte Raisonnée (starting with 1998 vintage) Régis Bouvier in Marsannay achieves a rare hat trick in Burgundy, the mastering of all three colors– red, white and rosé, through reasonable yields and high quality terroirs. Bouvier makes the best Burgundian rosé that we have ever tasted, his whites are delicious, with their own particular character completely unlike other Chardonnays from Burgundy, and his reds are his crowning achievement, managing to be wild and exciting while refined and elegant at the same time. Bouvier’s vineyards in Marsannay are premier-cru quality (some may even get classified) and his lieu- dit Bourgogne Rouge En Montre Cul vineyard is of a quality well above most (cultivated on a steep slope, not flatland Bourgogne). And don’t miss his Morey-St-Denis En la Rue de Vergy, a superb vineyard right above the Grand Cru Clos de Tart. This domaine represents terrific value for a number of reasons–a lesser-known appellation combined with quality vineyard holdings and a conscientious and talented wine grower. 1605 San Pablo Avenue, Berkeley, CA 94702 www.kermitlynch.com | [email protected] Berkeley Retail: 510.524.1524 | California Wholesale: 510.903.0440 | National Distribution: 707.963.8293 DOMAINE REGIS BOUVIER (continued) Vine Vineyard Wine Blend Soil Type Age Area* Avg. 35 Bourgogne Rouge Pinot Noir Limestone, -

In Vino Caritas

IN VINO CARITAS The Wine Burgundy June 29–July 2 Forum Excursion 2014 Contents Welcome to The Wine Forum 2 Schedule 4 The Burgundy Wine Region 6 The Producers 14 Festival Musique & Vin 20 Climats du Coeur 22 Biographies 24 1 Welcome to The Wine Forum June 29, 2014 Dear Member, Many wine lovers believe that Burgundy is home to the highest forms of Pinot Noir and So during our 2014 tour, we will combine our philanthropy towards the Climats du Coeur and Chardonnay grape varieties. With more than 1,500 years of cultivation, it is hard to argue against the Musique et Vin festival by holding an auction for special bottles donated by winemakers this belief. However, to The Wine Forum, Burgundy is more than just pure, scholarly wine. To us, whom we will be visiting and splitting the proceeds equally between these two worthy causes. Burgundy represents all that we as a group stand for—that is, that fine wine is not a right, but a And what a tour we have lined up! We commence with a Gevrey-Chambertin Grand Cru tasting privilege. Speaking with the region’s very top winemakers, they resolutely believe they are merely the current custodians of cherished plots, and that their role is to make the best wines possible at the Château du Clos de Vougeot on the final night of the 2014 Musique et Vin Festival. This and pass on the vineyard in the best condition possible to the next generation. Working the soil fabled region hosts 9 Grand Cru vineyards, the most of any in Burgundy. -

Bourgogne and Its Five Wine-Producing Regions

Bourgogne and its five wine-producing regions Dijon Nancy Chenôve CHABLIS, GRAND AUXERROIS & CHÂTILLONNAIS Marsannay-la-Côte CÔTE DE NUITS A 31 Couchey Canal de Bourgogne Fixin N 74 Gevrey-Chambertin Troyes Ource N 71 Morey-St-Denis Seine Chambolle-Musigny Hautes Côtes Vougeot Charrey- Belan- Gilly-lès-Cîteaux sur-Ource de Nuits Vosne-Romanée Flagey-Échezeaux Molesmes sur-Seine Massingy Paris Nuits-St-Georges Premeaux-Prissey D 980 A 6 Comblanchien Laignes Châtillon-sur-Seine Corgoloin Pernand-Vergelesses Tonnerre Ladoix-Serrigny CÔTE DE BEAUNE Montbard Aloxe-Corton Dijon Savigny-lès-Beaune Saulieu Chorey-lès-Beaune A 36 Besançon A 31 Hautes Côtes Pommard Troyes Beaune Troyes St-Romain Volnay Paris Armançon de Beaune N 6 Auxey- Monthélie Duresses Meursault Serein Joigny Yonne Puligny- Jovinien Ligny-le-Châtel Montrachet Épineuil St-Aubin Paris Villy Maligny Chassagne-Montrachet A 6 Lignorelles Fontenay- Tonnerre La Chapelle- près-Chablis Dezize-lès-Maranges Santenay Vaupelteigne Tonnerrois Chagny Poinchy Fyé Collan Sampigny-lès-Maranges CÔTE CHALONNAISE Beines Fleys Cheilly-lès-Maranges Bouzeron Milly N 6 Chablis Béru Viviers Dijon Auxerre Chichée Rully A 6 Courgis Couches Chitry Chemilly- Poilly-sur-Serein Mercurey Vaux Préhy St-Bris- sur-Serein Couchois Dole le-Vineux Chablisien St-Martin N 73 Noyers-sur-Serein sous-Montaigu Coulanges- Irancy A 6 Dracy-le-Fort la-Vineuse Canal du Centre Chalon-sur-Saône Cravant Givry Auxerrois Val-de- Nitry Mercy Vermenton Le Creusot r N 80 Clamecy Dijon Lyon Buxy Vézelien Montagny-lès-Buxy Saône Jully- -

The Burgundy Report Vintages 2009 & 2010

J.J. BUCKLEY FINE WINES The Burgundy Report Vintages 2009 & 2010 web: jjbuckley.com phone: 888.85.wines (888.859.4637) email: [email protected] twitter: @jjbuckleywines 7305 edgewater drive, suite d | oakland, ca 94621 2010 BURGUNDY REPORT Authors Chuck Hayward Christopher Massie Editors Paige Granback Deborah Adeyanju Alexandra Fondren Contributing Writers Cory Gowan John Sweeney All photography supplied by Chuck Hayward. All rights reserved. For questions or comments, please email: [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introducing Burgundy 3 Burgundy: A History 4 Hierarchies in Burgundy 6-8 The Region 9-15 House Styles 16 Vintages in Burgundy 17-19 The Negociants 20-21 Negociant profiles 22-25 An American in Burgundy 26-28 Where to Wine and Dine 29-32 The Future of Burgundy 33-36 Winery Profiles and Tasting Notes 37-98 About This Report 99 3 INTRODUCING BURGUNDY Burgundy is a unique part of the wine culty in growing the grape and fashion- experiencing such a wine, the need to world. Its viticultural history extends ing it into wine is well known. Finally, experience it again and again exerts an back two thousand years. It has pro- the vineyards have been divided and irresistible pull. The search becomes as duced wines that inspired great literary subdivided into plots of various sizes exciting, if not more so, than drinking works. Its vineyards are known and names, then ranked according to the wine. throughout the world and its wines their designated quality level. What you Adopting the idea that pinot represents command some of the highest prices. -

Masters List

Masters List CHAMPAGNE brut G-605 2006 Dom Perignon 240. G-907 NV Krug Grand Cuvee 250. G-905 2003 Krug Vintage 300. G-604 2002 Pol Roger Cuvee Sir Winston Churchhill 285. G-706 2002 Cristal 330. G-706 2004 Cristal 330. G-509 2006 Cristal 285. rosé G-604 2004 Perrier Jouet Fleur Rose 325. FRANCE whites G-902 2014 Arnaud Ente 1er Cru Champ Gains, Puligny-Montrachet 350. G-408 2014 Arnaud Ente 1er Cru Les Referts Puligny-Montrachet, Burgundy 350. G-603 2010 Nicolas Potel Grand Cru Corton-Charlemagne, Burgundy 260. G-307 2013 Follin Arbelet Grand Cru Corton-Charlemagne, Burgundy 285. reds G-708 2015 Forrier 1er Cru Cherbaudes, Gevery-Chambertin 225. G-904 2005 Hubert Camus Grand Cru Latricières-Chambertin, Burgundy 200. C-513 2005 Hubert Camus Grand Cru Charmes-Chambertin, Burgundy 200. D-910 2002 Hubert Camus Grand Cru Charmes-Chambertin, Burgundy 180 C-515 2005 Camus Grand Cru Charmes-Chambertin, Gevery-Chambertin mag 500. G-802 2014 Mommessin Monopole Grand Cru Clos de Tart , Morey St-Denis 495. G-306 2005 Pascal Lacheaux Grand Cru Clos-St-Denis, Morey St-Denis 225. G-504 2009 Follin Arbelet Grand Cru Romanee-Saint-Vivant, Vosne Romanee 400. G-208 2010 Follin Arbelet Grand Cru Romanee-Saint-Vivant, Vosne Romanee 400. G-403 2011 Jean Grivot Grand Cru Echezeaux, Vosne Romanee 240. G-404 2009 Pichon Longueville Reserve de la Comtesse, Pauillac, Bordeaux 190. G-807 2010 Chateau Palmer ‘Alter Ego,’ Margaux, Bordeaux 240. G-806 2009 Jaboulet ‘La Chapelle,’ Hermitage, Northern Rhone 300. G-503 2010 Jaboulet ‘La Chapelle.’ Hermitage, Northern Rhone 300. -

The Burgundy Wine Region & Dijon

VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com France: The Burgundy Wine Region & Dijon Bike Vacation + Air Package In Burgundy, France bike routes traverse some of the world’s most famous vineyards. Spinning from Lyon to Dijon—two UNESCO-designated urban showpieces—you’ll cycle mellow hills bursting with grapes cultivated for the region’s celebrated wines. Pause at charming stone towns imbued with wine and gastronomic tradition. Explore the 15th-century Hospices de Beaune, a masterpiece of flamboyant Gothic art and architecture and Burgundy’s most visited site. In Dijon museums, browse fine arts and sacred artifacts. Follow bike paths along canals and into wine villages with thriving local markets. The bucolic scenery here has made this route a favorite among travelers for its lush, unspoiled countryside. Cultural Highlights Cycle through the bucolic countryside where Chardonnay wine originated and has been produced for centuries. 1 / 9 VBT Itinerary by VBT www.vbt.com Shop a local market in Cluny, with a backdrop of its 10th-century Benedictine abbey. Pass renowned wine villages rolling through the world-famous vineyards of the Côte de Beaune and UNESCO World Heritage Route des Grands Crus. Visit the 15th-century Hospices de Beaune, a masterpiece of flamboyant Gothic art and architecture. Enjoy a guided tour and tasting at an authentic wine cellar in the heart of Beaune. Engage with a local family during a game of pétanque and a picnic lunch at their charming summer home. Discover Dijon with its protected historic city center that has inspired musicians, artists, and writers for centuries, and browse its wealth of fascinating—and free—museums. -

Dijon Auxonne Dijon

DIJON AUXONNE DIJON Dimanche 14 Avril 2019 Complexe de Louzole, St Apollinaire : 12h30 Arrivée Avenue Jean Bertin : 16h00 Prix d’attente Avenue Jean Bertin dès 14h00 Comité d’Organisation L’épreuve Chatillon-sur-Seine/Dijon est placée sous la direction de M. Bernard Mary, Président du SCO Dijon M. Bernard Mary M. Benoît Perrin Mme Marie-Christine Sire Organisateur Resp. Organisation Trésorière 06 10 75 78 50 06 30 57 80 60 06 42 20 61 56 Mme Colette Orsat M. Pierre Lescure Arbitre Resp Engagement Communication 06 82 40 05 98 06 29 87 96 34 Course Directeur de l’organisation : Bernard MARY Médecin : Didier OTTIGER (06.76.28.99.48) Directeur de course : Bernard MARY Direct Vélo : Christian COSSERAT Communiqué de presse : Colette ORSAT Voiture Ouvreuse: SCO Dijon Ardoisière : Mireille MENISSIER Ambulances : NYCOLL (06.02.48.33.75) Dépannage en course : 1. Denis REPERANT Speaker officiel : Jean Michel QUERRE 2. Christian COLLOT Lignes d’arrivée : Alain PERRIN Radio tour : DI@LOG Zones départ : Benoit PERRIN Moto information : Tom LEMENTEC Protocoles aux arrivées : Pierre LESCURE Photo finish : SCO DIJON Responsable invités et Partenaires : Pierre LESCURE Classement : Colette ORSAT Motos Sécurité et Signaleurs : SCO DIJON Liaisons Radio Course : DI@LOG Voiture Balai : SCO DIJON Arbitres Officiels Président du jury : Dominique COUTANT Arbitre 1 : Yvon JOFFRAIN Arbitre 2 : Joël MELZER Arbitre moto 1 : Julien COUTANT Arbitre moto 2 : Philippe GUITARD Juge arrivée : Jean Paul GIRARD Permanence Départ : 10h15 Ligne d’arrivée: Complexe de Louzole, -

Early Modern Burgundian Hospitals As Catalysts of Independent Political Activity Among Women: Lay Nurses and Electoral Empowerment, 1630- 1750

Early Modern Burgundian Hospitals as Catalysts of Independent Political Activity Among Women: Lay Nurses and Electoral Empowerment, 1630- 1750 Kevin C. Robbins Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis This essay investigates the largest secular healthcare network in early modern Europe in which lay women took vital roles as professional nurses, pharmacists of renown, and powerful, highly conscientious administrators. By 1750, this organization encompassed at least fifty-five municipal and charity hospitals of varying size located in towns throughout eastern France and western Switzerland. These hospitals were all direct outgrowths of the remarkable Hôtel-Dieu (les hospices civils) in the Burgundian town of Beaune and its institutional satellites. At each site, patient care, nurse training, pharmacology, and many aspects of internal governance became the responsibility of an extensive, closely bound consorority of lay women trained under and showing enduring fidelity for centuries to the secular governing rules of the mother-house in Beaune. My study is a comparative one. It relates notable confrontations between lay female nurses and potent external antagonists at the highest echelons of the French clergy. The hospitals involved are the civil hospital of Chalon-sur-Saône (also known as the Hôpital de St. Laurent) and the Hôtel-Dieu of Dole in the adjoining province of Franche-Comté. At both sites, the nurses and their internal, secular protocols of politics and governance drawn from Beaune became the targets of senior Catholic prelates intent on remaking and controlling the nurses' vocation. These churchmen both misunderstood the lay status of the nurses and entirely underestimated their resolute, resourceful defense of their ancient electoral and administrative liberties.