ECWA) Towards Islam in Light of Ethnic and Religious Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contending Perspectives and Security Implications of Herdsmen Activities in Nigeria

[Enor et. al., Vol.7 (Iss.7): July 2019] ISSN- 2350-0530(O), ISSN- 2394-3629(P) DOI: https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v7.i7.2019.765 Social CONTENDING PERSPECTIVES AND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF HERDSMEN ACTIVITIES IN NIGERIA Frank. N. Enor 1, Stephen E. Magor 1, Charles E. Ekpo 2 1 Department of History & International Studies, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria 2 Peace and Conflict Studies Programme, Institute for Peace and Strategic Studies, University of Ibadan, Ibadan – Nigeria Abstract This paper submits that there exist multiple dimensions through which herdsmen attack in Nigeria could be perceived. Though traditionally seen as violence anchored on resource conflict, the attacks inhibit acts of terror and in some instances, religious extremism. Also, the word farming was substituted for the phrase “farming communities” because victims of herdsmen attacks are all not farmers. Importantly, this paper emphasizes the word “herdsmen” in place of the popular and ethnically charged phrase “Fulani- herdsmen” because, although predominantly of Fulani stock, not all herdsmen are ethnic Fulani. There is a perception that the rising state of these attacks is nothing other than a conspiracy by some influential forces within the country, and in the opinion of others the attacks embeds acts of criminality. This paper argues that beyond the perception of resource conflict, issues of terrorism, religious extremism, conspiracies and criminality are but new perspectives with which herdsmen attacks in Nigeria could be understood; and within these perspectives lie various security challenges that require multiple strategic solutions. The researchers consulted several secondary and tertiary sources, especially newspaper reports. Keywords: Security; Jihad; Terrorism; Resource Conflict; Herdsmen Violence; Conspiracy Theory; Criminality; Religious Extremism. -

Johasam 2018

JOHASAM JOURNAL OF HEALTH, APPLIED SCIENCES AND MANAGEMENT Volume 2, November, 2018 Editor Iheanyi Osondu Obisike © 2018 Rivers State College of Health Science & Technology ISSN: 1597-7085 Published by RIVERS STATE COLLEGE OF HELATH SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY KM 6 IKWERRE ROAD, RUMUEME PORT HARCOURT, NIGERIA @ WELLINGTON PRINTING PRESS No. 85b Azikiwe/Iloabuchi Street Mile 2 Diobu, Port Harcourt JOHASAM: Journal of Health, Applied Sciences and Management Editor Iheanyi Osondu Obisike Associate Editors Mandy George Unwobuesor Richard Iloma Edwin Isotu Edeh John Hemenachi S. Nwogu Ibiene Kalio Journal of Health, Applied Sciences and Management (JOHASAM) is a high quality peer-reviewed research journal which provides a platform for researchers, academics, health professionals and management experts to share universal knowledge on health science, technology and management in order to produce efficient, self-reliant and enterprising manpower that would meet the challenges of contemporary health care delivery services and management. We welcome quality research papers on these areas: Community Health, Public Health, Environmental Health, Medical Imaging Laboratory Science, Pharmacy, Dispensing Opticianry, Dentistry, General Medicine, Anatomy, Health Educaiton, Medical Social Work, Medical Sociology, Rural Sociology, Social Sciences, Biomedical Engineering, Physics, Biology, Chemistry, Physiology, Psychology, Entrepreneurship, Hospital Management, and all Science-based Courses. Reference style: APA Send your manuscript to the editor at: [email protected] or call the following numbers: 07062527544, 08037736670 Publication Fee: 15,000 Bank Details Account Name: Rivers State College of Health Science & Technology (Investment A/C) Bank: Ecobank Account No.: 5482007692 JOHASAM Journal of Health, Applied Sciences and Management volume 2, November, 2018 Contents Influence of Demographic Variables on Knowledge of Hypertension Among Residents of Obio/Akpor Local Government Area of Rivers State Itaa Patience & E. -

Nigeria 2014 NTBLCP Annual Report DEPARTMENT of PUBLIC HEALTH

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH NATIONAL TUBERCULOSIS & LEPROSY CONTROL PROGRAMME Nigeria 2014 NTBLCP Annual Report 0 2014 NTBLCP Annual Report Acknowledgements National Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Buruli Ulcer Control Programme (NTBLCP) in this 2014 annual report has compiled the activities carried out by the programme from January to December 2014. In line with our procedure, both the achievements and challenges encountered during the year in view were outlined. Our heartfelt gratitude goes to the Federal Ministry of Health through the Head of Department of Public Health, Dr. Bridget Okoeguale for the good managerial coordination and passionate drive to achieve our set targets. All of these achievements have been made possible through the inspiration of the Honourable Minister of Health, Dr. Alhassan Khaliru, whose desire is to actualize the transformation agenda of the President and commander-in -chief of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, His Excellency Dr. Goodluck Ebele Jonathan. We also want to thank the staff of TBL & BU control programme at both Federal, State, and local Government levels, the World Health organization National Professional Officers (WHO NPOs), ILEP partners, the PRs for GFATM and all national/international Consultants to GFATM for joining in implementing the strategic plan for the interventions and control of Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Buruli ulcer in the year 2014. Our achievements would not have been possible without their commitment. Our Special appreciation is to the Global Fund, the USAID (KNCV, MSH, FHI360 and Abt. Associates), the CDC, WHO, other technical and financial partners who have contributed tremendously to the progress achieved by the NTBLCP in the year under review. -

Death and the Textile Industry in Nigeria

Death and the Textile Industry in Nigeria This book draws upon thinking about the work of the dead in the context of deindustrialization—specifically, the decline of the textile industry in Kaduna, Nigeria—and its consequences for deceased workers’ families. The author shows how the dead work in various ways for Christians and Muslims who worked in KTL mill in Kaduna, not only for their families who still hope to receive termination remittances, but also as connections to extended family members in other parts of Nigeria and as claims to land and houses in Kaduna. Building upon their actions as a way of thinking about the ways that the dead work for the living, the author focuses on three major themes. The first considers the growth of the city of Kaduna as a colonial construct which, as the capital of the Protectorate of Northern Nigeria, was organized by neighborhoods, by public cemeteries, and by industrial areas. The second theme examines the establishment of textile mills in the industrial area and new ways of thinking about work and labor organization, time regi- mens, and health, particularly occupational ailments documented in mill clinic records. The third theme discusses the consequences of KTL mill workers’ deaths for the lives of their widows and children. This book will be of interest to scholars of African studies, development studies, anthropology of work, and the history of industrialization. Elisha P. Renne is Professor Emerita in the Departments of Anthropology and of Afroamerican and African Studies, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, USA. Routledge Contemporary Africa Series Corporate Social Responsibility and Law in Africa Theories, Issues and Practices Nojeem A. -

Continental J. Nursing Science 4 (1): 34

Continental J. Nursing Science 4 (1): 34 - 46, 2012 ISSN: 2141 - 4173 © Wilolud Journals, 2012 http://www.wiloludjournal.com Printed in Nigeria doi:10.5707/cjnsci.2012.4.1.34.46 EVALUATION OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF NURSING PROCESS AMONG NURSE CLINICIANS 1Afoi, BB, 2Emmanueul, A, 3Garba, SN, Gimba, SM and Afuwai, V. 1College of Nursing and Midwifery, Kafanchan, 2Department of Nursing Science, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Jos, 3Department of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, 4Department of Human Anatomy, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. ABSTRACT This research was carried out in Kaduna State, Nigeria to determine whether Nursing Process is used in patients care or not. Utilizing an ex-post facto research design, a multistage sampling technique was used to select 210 nurses from urban and rural based hospitals from the three (3) senatorial districts of Kaduna State. Self-administered questionnaires were used for data collection. About 78% (163) of the questionnaire was filled and returned. The major findings were that 57.1% of the respondents indicated that Nursing Process is used in patients care in Kaduna state General Hospitals while 14.1% revealed that the use of nursing process started and stopped and 25.8% indicated that it is not used in patients care. The major factors that militated against the implementation of Nursing Process were identified as shortage of nursing staff (54.0%) and insufficient equipment (28.2%) for the implementation of Nursing Process in patients care. Three null hypotheses tested at significant level of 0.05 indicated that, years of experience and qualification does not relate significantly with the implementation of nursing process but rank of nurses relates significantly with the implementation of nursing process. -

Policy Brief on Free Treatment for Pregnant Women and Under 5 Children In

Policy Brief on Free Treatment for Pregnant Women and Under 5 Children in Kaduna State Ministry of Health, Kaduna State List of Acronyms ANC Antenatal Clinic APH Ante Partum Haemorrhage ARI Acute Respiratory Infections AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome BEOC Basic Emergency Obstetric Care BF Blood film CIMCI Community – IMCI CWC Child Welfare Committee CSF Cerebro-spinal Fluid CEOC Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care CXR Chest X-Ray CS Caesarean Section DRF Drug Revolving Fund FMS Financial Management Systems HIV Human Immunodeficciency Virus HC Health Centre HB Haemoglobin HMIS Health Management Information Systems ITN Insecticide Treated Nets IPT Intermittent Prophylactic Treatment IMCI Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses IPCC Inter Personal Communication and Counselling KADSEEDS Kaduna State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy LGA Local Government Area LSS Life Saving Skills MCH Maternal and Child Health M & E Monitoring and Evaluation NPI National Programme on Immunisation OPD Out Patient Department OIC Officer In- Charge PHC Primary Health Care PHCDA Primary Health Care Development Agency PPH Post Partum Haemorrhage SMOH State Ministry of Health SHC Secondary Health Care 2 Ministry of Health, Kaduna State Policy Context • Development of a National Health Management Systems that coordinates all levels and programmes • Primary Health Care Policy with focus on access for all • Millennium Development Goals for accelerated achievement of targets • Priority health interventions: Reproductive health, Child health (including immunization), HIV/AIDS, Malaria, Tuberculosis and Leprosy • KADSEEDS emphasis on social charter and accountability • Drug Revolving Fund Scheme for access to essential medicines • Exemptions and free service policies e.g. NPI Guiding Principles • Access (geographical and financial) to care • Equity in provision • Partnership for health development • Community Participation at every stage Strategic Objectives By 2009 • Maternal Health. -

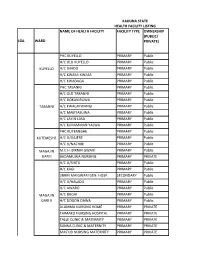

List of Coded Health Facilities in Kaduna State.Pdf

KADUNA STATE HEALTH FACILITY LISTING NAME OF HEALTH FACILITY FACILITY TYPE OWNERSHIP (PUBLIC/ LGA WARD PRIVATE) PHC KUYELLO PRIMARY Public H/C OLD KUYELLO PRIMARY Public KUYELLO H/C SHADO PRIMARY Public H/C KWASA-KWASA PRIMARY Public H/C KWADAGA PRIMARY Public PHC TABANNI PRIMARY Public H/C OLD TABANNI PRIMARY Public H/C DOKAN RUWA PRIMARY Public TABANNI H/C KWALAKWANGI PRIMARY Public H/C MAIKYASUWA PRIMARY Public H/C LAYIN LASA PRIMARY Public H/C K/MAMMAN YALWA PRIMARY Public PHC KUTEMESHE PRIMARY Public KUTEMESHE H/C U/GAJERE PRIMARY Public H/C U/NACHIBI PRIMARY Public MAGAJIN M.C.H. BIRNIN GWARI PRIMARY Public GARI I BADAMUWA NURSING PRIMARY PRIVATE H/C U/SHITU PRIMARY Public H/C KAGI PRIMARY Public JIBRIN MAIGWARI GEN. HOSP. SECONDARY Public H/CB/GWARI U/HALADU PRIMARY Public H/C AWARO PRIMARY Public MAGAJIN H/C BUGAI PRIMARY Public GARI II H/C DOGON DAWA PRIMARY Public ALUMMA NURSING HOME PRIMARY PRIVATE TAIMAKO NURSING HOSPITAL PRIMARY PRIVATE TALLE CLINIC & MATERNITY PRIMARY PRIVATE SUNNA CLINIC & MATERNITY PRIMARY PRIVATE MAS'UD NURSING MATERNITY PRIMARY PRIVATE BIRNIN GWARI PHC SAULAWA PRIMARY Public H/C MAGANDA PRIMARY Public H/C KIKAZO PRIMARY Public MAGAJIN H/C GWASKA PRIMARY Public GARI III H/C GWAURON DUTSE PRIMARY Public H/C OLD B/GWARI PRIMARY Public H/C LAYIN MAIGWARI PRIMARY Public H/C KAMFANIN DOKA PRIMARY Public H/C MANDO PRIMARY Public H/C GRASING PRIMARY Public H/C KIRAZO PRIMARY Public GAYAM H/C FOLWAYA PRIMARY Public BIRNIN GWARI H/C GAYAM PRIMARY Public H/C LABI PRIMARY Public H/C RUMANA GWARI PRIMARY Public H/C KWAGA PRIMARY Public MPHC DOGON DAWA PRIMARY Public DOGON H/C U/DANKO PRIMARY Public DAWA H/C SAMINAKA PRIMARY Public H/C FUNTUWAN BADADI PRIMARY Public PHC DAMARI PRIMARY Public H/C TAKAMA PRIMARY Public KAZAGE H/C GWANDA PRIMARY Public (DAMARI) H/C INGADE PRIMARY Public DIRAYO CLINIC & MATERNITY PRIMARY PRIVATE PHC KAKANGI PRIMARY Public M.P.H.C. -

International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews Vol.5 No.1, 2015

International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews Vol.5 No.1, 2015 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES REVIEW First Publication 2015 www.ijsshr.com Copyright @ International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Review ISSN 2276 - 8645 Published by Platinumlink Communication Services, Abakaliki. VOL.5 NO.1 FEBRUARY 2015. I International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Reviews Vol.5 No.1, 2015 Guidelines for Submission of Articles Authors are to submit clear copies of manuscripts type-written, double-spaced on A4 paper with margin on both sides not more than 15-20 pages in length including abstract and references. The title pages of Articles should carry the authors names, status, addresses, place of work e-mail address and phone numbers and abstract about 250 words (with at least five key words). Manuscripts are received on the understanding that they are original and unpublished works of authors not considered for publication else where Current APA style of referencing should be maintained. Figures, tables, charts and drawing should be clearly drawn and the position marked in the text. All manuscripts and other editorial materials should be directed to the: Editor-in-chief Dr. Oteh, Chukwuemeka Okpo Department of Sociology/Anthropology Kogi State University, Anyigba, Kogi State e-mail: [email protected] Phone: +2348034356286 OR Dr. E.B.J Iheriohanma Directorate of General Studies Federal University of Technology, P.M.B 1526 Owerri, Imo State Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] All online submission of Articles should be forwarded to: www.ijsshr.com Please visit our website at www.ijsshr.com for direction on how to submit papers online. -

Aliyu Gambo Gumel Permanent E-Mail Address

Pattern of Mycobacterial Infections and their Associations with HIV among Laboratory Confirmed Cases of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Nigeria Item Type dissertation Authors Aliyu, Gambo Gumel Publication Date 2012 Abstract Background: Nigeria has the fourth highest tuberculosis (TB) burden worldwide. In this study, mycobacterial agents from clinically symptomatic TB patients, regardless of HIV co-infection were isolated and characterized, and resistance to isoniazid an... Keywords non-tuberculous; HIV Infections; Mycobacterium; Nigeria; Tuberculosis, Pulmonary Download date 02/10/2021 08:51:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10713/2224 CURRICULUM VITAE Name: Aliyu Gambo Gumel Permanent e-mail Address: [email protected] Degree and Date to be Conferred: Ph.D., 2012 Collegiate Institutions Attended: University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD Ph.D., Epidemiology, 2012 M.S., Clinical Research, 2008 Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria MB.BS, Medicine 1995 Professional Publications: 1. Aliyu G., Mohammad M., Saidu A., Mondal P., Charurat M., Abimiku A., Nasidi A., Blattner W. HIV Infection Awareness and Willingness to Participate in Future HIV Vaccine Trials across Different Risk Groups in Abuja, Nigeria. AIDS Care; July, 2010 (1-8) 2. Aliyu G ., Informed Consent of Very Sick Subjects in Nigeria. Account Res. 2011 Jul-Aug; 18:4, 289-296 3. Charurat M, Nasidi A, Delaney K, Saidu A, Croxton T, Mondal P, Aliyu GG , Constantine N, Abimiku A, Carr JK, Vertefeuille J, Blattner W. Characterization of acute HIV-1 infection in high-risk Nigerian populations, J Infect Dis. 2012 Apr; 205(8):1239-47. Epub 2012 Feb 21 4. Sani-Gwarzo Nasiru, Gambo G. Aliyu , Alex Gasasira , Muktar H. -

Genexpert Optimization

Institute Of Human Virology-Nigeria BID DOCUMENT International Competitive Bidding BID TITTLE: Optimization of GeneXpert Sites ITB No.: ITB/IHVN/GF PPM/001/2020 MANAGEMENT OF XPERT MTB/RIF MACHINE OPTIMIZATION FOR 37 LOTS Country: Nigeria Issued on: 25th January, 2021. Abbreviations and Acronyms A Ampère AC Alternative Current AMP Ampere Ah Ampere Hour AWG American Wire Gauge BDS Bid Data Sheet CV Curriculum Vitae cm Centimetre DC Direct Current CPT Carriage Paid To EVA Ethylene Vinyl Acetate EQ Equalizer GF Global Fund GFP Ground Fault Protectors G Gram HSE Health, Safety and Environmental IHVN Institute of Human Virology-Nigeria ITB Invitation to Bid INCOTERM International Commercial Term JV Joint Venture kVA Kilo Volt Amperes kWh Kilowatt-Hour LOI Letter of Interest M Meter MCB Miniature Circuit Breaker mm Millimeter MHz Megahertz mA Milliampere NGN Nigerian Naira N/A Not Applicable OFCCP Office of Federal Contract Compliance Program V Volt VA Volt Ampere SOP Standard Operating Procedures PO Purchase Order SQ MM Square Meter W Watt Wp Watt peak °C Degree Celsius % Percentage Page 2 of 67 Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 2 Section I. LETTER OF INVITATION ............................................................................................................ 4 Section II. INSTRUCTION TO BIDDERS (ITB) ............................................................................................ -

Colonialism in the Stateless Societies of Africa

African Social Science Review Volume 8 Article 3 Number 1 Spring 2016 Colonialism in the Stateless Societies of Africa: A Historical Overview of Administrative Policies and Enduring Consequences in Southern Zaria Districts, Nigeria Aliyu Yahaya Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr Recommended Citation Yahaya, Aliyu () "Colonialism in the Stateless Societies of Africa: A Historical Overview of Administrative Policies and Enduring Consequences in Southern Zaria Districts, Nigeria," African Social Science Review: Vol. 8: No. 1, Article 3. Available at: http://digitalscholarship.tsu.edu/assr/vol8/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Scholarship @ Texas Southern University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African Social Science Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship @ Texas Southern University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Yahaya: Colonialism in the Stateless Societies of Africa: A Historical Ov Colonialism in the Stateless Societies of Africa: A Historical Overview of Administrative Policies and Enduring Consequences in Southern Zaria Districts, Nigeria Aliyu Yahaya Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria Abstract: An unapologetic perspective in the study of colonialism in Africa is currently reasserting itself forcefully. It sees the colonial experience as a mere sporadic change initiated by the need to use traditional institutions in the administration of the natives. It assumes that the responses of the natives had imposed some restrictions on the creative disposition of the colonial overlords. With evidence from some Stateless societies of Nigeria this article shows that colonialism had been occasioned by currents that denaturalized the social order to the extent that traditional institutions used lost their traditionalness hence ushering changes that were decisive in nature and far reaching in consequence. -

An Analysis of Utilization of Traditional Medicine in Kaduna State, Nigeria

AN ANALYSIS OF UTILIZATION OF TRADITIONAL MEDICINE IN KADUNA STATE, NIGERIA BY JACOB SHEKARI KURA GANDU DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA, NIGERIA MAY, 2019 i AN ANALYSIS OF UTILIZATION OF TRADITIONAL MEDICINE IN KADUNA STATE, NIGERIA BY JACOB SHEKARI KURA GANDU (P16SSSG9037) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN SOCIOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, NIGERIA MAY, 2019 ii DECLARATION I declare that the work in this dissertation entitled, ‘An Analysis of Utilization of Traditional Medicine in Kaduna State, Nigeria‘ has been performed by me in the Department of Sociology, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided. No part of this dissertation was previously presented for another degree or diploma at this or any other Institution. Jacob Shekari Kura GANDU ____________________ __________________ Name of Student Signature Date iii CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled AN ANALYSIS OF UTILIZATION OF TRADITIONAL MEDICINE IN KADUNA STATE, NIGERIA BY JACOB SHEKARI KURA GANDU meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) of the Ahmadu Bello University, and is approved for its‘ contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Dr (READER) J. M. HELLANDENDU