Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea Development Infrastructure Funding Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Weekly List & Decisions

Planning Weekly List & Decisions Appeals (Received/Determined) and Planning Applications & Notifications (Validated/Determined) Week Ending 27/11/2020 The attached list contains Planning and related applications being considered by the Council, acting as the Local Planning Authority. Details have been entered on the Statutory Register of Applications. Online application details and associated documents can be viewed via Public Access from the Lambeth Planning Internet site, https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/planning-and-building- control/planning-applications/search-planning-applications. A facility is also provided to comment on applications pending consideration. We recommend that you submit comments online. You will be automatically provided with a receipt for your correspondence, be able to track and monitor the progress of each application and, check the 21 day consultation deadline. Under the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any comments made are open to inspection by the public and in the event of an Appeal will be referred to the Planning Inspectorate. Confidential comments cannot be taken into account in determining an application. Application Descriptions The letters at the end of each reference indicate the type of application being considered. ADV = Advertisement Application P3J = Prior Approval Retail/Betting/Payday Loan to C3 CON = Conservation Area Consent P3N = Prior Approval Specified Sui Generis uses to C3 CLLB = Certificate of Lawfulness Listed Building P3O = Prior Approval Office to Residential DET = Approval -

Oval Triangle Consultation Report

Junction improvements at Oval Triangle Response to consultation October 2014 Contents 1 Background ................................................................................................................ 3 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 4 3 The consultation ......................................................................................................... 5 4 Responses to the consultation .................................................................................... 7 5 The Oval Triangle consultation questionnaire ........................................................... 10 6 Location-specific issues ............................................................................................ 13 7 Summary of stakeholder responses to the consultation ............................................ 20 8 Improvements to the Oval Triangle green space ..................................................... 22 9 Conclusion ............................................................................................................... 23 Appendix A Response to issues commonly raised ..................................................... 24 Appendix B – Consultation letter and map ....................................................................... 28 Appendix C – Consultation letter distribution area ........................................................... 31 Appendix D – List of stakeholders consulted .................................................................. -

Weekly List & Decisions

Planning Weekly List & Decisions Appeals (Received/Determined) and Planning Applications & Notifications (Validated/Determined) Week Ending 25/06/2021 The attached list contains Planning and related applications being considered by the Council, acting as the Local Planning Authority. Details have been entered on the Statutory Register of Applications. Online application details and associated documents can be viewed via Public Access from the Lambeth Planning Internet site, https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/planning-and-building- control/planning-applications/search-planning-applications. A facility is also provided to comment on applications pending consideration. We recommend that you submit comments online. You will be automatically provided with a receipt for your correspondence, be able to track and monitor the progress of each application and, check the 21 day consultation deadline. Under the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any comments made are open to inspection by the public and in the event of an Appeal will be referred to the Planning Inspectorate. Confidential comments cannot be taken into account in determining an application. Application Descriptions The letters at the end of each reference indicate the type of application being considered. ADV = Advertisement Application P3J = Prior Approval Retail/Betting/Payday Loan to C3 CON = Conservation Area Consent P3N = Prior Approval Specified Sui Generis uses to C3 CLLB = Certificate of Lawfulness Listed Building P3O = Prior Approval Office to Residential DET = Approval -

Section 1 – Site Location Map

SECTION 1 – SITE LOCATION MAP SECTION 2 – APPLICATION SUMMARY Freedom Shipping Ltd, 3 Mepham Street, London Site address SE1 8FS Ward Bishop’s Change of use from Offices (Use Class B1) to Proposal Restaurant (Use Class A3) together with the installation of a new shopfront and external duct flue. Application type Other minor 13/04714/FUL Application ref(s) 14 th October 2013 Validation date Name: Magdalena Kotyza Case officer details Tel: 020 7926 1270 Email: [email protected] Applicant Mr Nick Hill (Black and Blue Waterloo Limited) Agent Mr Michael Black (Fusion design & Architecture) Considerations/constraints Kennington Cross Neighbourhood Association South Bank Employers Group Waterloo Opportunity Area Environment Agency Flood Zone Central Activities Zone Approved plans Drawings ref: 132-09/100; 101; 103; 200B; 250A; 400; 401B; 402; Design and Access Statement; Floor Risk Assessment; Permanent Suspension Modules details; Recommendation(s) Grant planning permission subject to conditions. Consulted? Date Response Department(s) or Organisation(s) Received Internal Neighbourhood Regeneration Project Y No response Manager Planning Policy Y No response Regulatory Services - Noise Pollution Y No response Regulatory Services - Food Safety Y No response Streetcare Y No response Conservation & Design Y 16.12.13 Transport/Highways Y 02.12.13 External Association of Waterloo Groups Y No response Lambeth Estates Residents Association Y No response Waterloo Community Development Group Y No response Friends Of Hatfield Green Y No response Friends -

Oval and Kennington Development Area

OVAL AND KENNINGTON DEVELOPMENT AREA MASTERPLAN DOCUMENT MAY 2016 INTRODUCTION 2 CONTENTS 01 INTRODUCTION AND VISION 02 CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS INTRODUCTION CONTEXT 1.1 Introduction 2.1 OAKDA’s Wider Context 1.2 Vision 2.2 OAKDA’s Local Context MASTERPLAN 1.3 The Opportunity 2.3 Site Overview 2.4 Planning Context HERITAGE 2.5 Public Consultation COMMERCIAL 2.6 Opportunities and Constraints RESIDENTIAL MOVEMENT 03 MASTERPLAN RESPONSE PUBLIC REALM 3.1 Illustrative Masterplan 3.2 Mixed Use Regeneration BUILT FORM 3.3 Sustainable Regeneration CONCLUSION 3.4 Successful Regeneration 04 HERITAGE 05 COMMERCIAL USE 06 RESIDENTIAL USE 07 MOVEMENT 08 PUBLIC REALM 09 BUILT FORM 4.1 History of the Area 5.1 Introduction to Commercial 6.1 Residential Context 7.1 Strategic Transportation 8.1 Open and Play Space 9.1 Strategic Heights 4.2 Heritage Assets 5.2 Employment 6.2 Housing Layout 7.2 Existing Access for Pedestrians 8.2 Local Landscape Character 9.2 Building Heights and Townscape 4.3 Gas Holders 5.3 Retail 6.3 Housing Assessment 7.3 Existing Access for Vehicles 8.3 Public Space Strategy 9.3 Potential Impact on Neighbours 4.4 Conservation Areas 5.4 Tourism and Culture 7.4 Pedestrian and Cycle Priority 8.4 Landscape Masterplan 9.4 Urban Grain and Frontages 4.5 Proposals for Heritage Assets 5.5 “Voho” 7.5 Car Access and Parking 8.5 Quantum of Open Space 9.5 Frontages and Building Plots 4.6 Heritage Themes 5.6 “Voho” Cultural Mapping 7.6 Servicing and Access Routes 8.6 Character of Public Spaces 9.6 Massing Principles 4.7 Case Studies 5.7 Social Infrastructure -

Written Answers to Questions Not Answered at Mayor's Question Time on 30 January 2013

Written Answers to Questions Not Answered at Mayor's Question Time on 30 January 2013 Rail travel in London Question No: 2013/0001 Caroline Pidgeon What steps are you taking to improve rail travel for Londoners? The Mayor Boris Johnson (Mayor of London): Yes, Caroline, you ask a very open ended question about what I am doing to improve rail travel for Londoners. There is a huge amount. I would just point out that, on the Overground for instance where we just completed the orbital loop, you have an increase in passenger satisfaction from 71% to 93%. Ridership has gone up from 25 million to 67 million, a massive increase both in satisfaction and numbers using our rail service. The orbital link that we opened from Surrey Quays to Clapham Junction - and you and Val [Shawcross AM] have made the point about the loss of the old South London Line - that is now carrying four times as many passengers as its predecessor service, and of course we will continue to lobby the Department for Transport (DfT) about the South London Line for which you have both campaigned. We are going to push on with what I think is a very promising campaign which I believe will be successful to get more democratic control for London over some of the metro franchises, and you will know what I am talking about. On Southeastern and Greater Anglia services we do think there is real scope for improvement in the turn up and go service, even at off peak times, making sure that stations are cleaner and safer with better signage, introducing Oyster even to areas outside London that do not currently have it. -

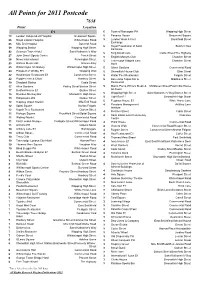

Points Asked How Many Times Today

All Points for 2011 Postcode 7638 Point Location E1 6 Town of Ramsgate PH Wapping High Street 73 London Independent Hospital Beaumont Square 5 Panama House Beaumont Square 66 Royal London Hospital Whitechapel Road 5 London Wool & Fruit Brushfield Street Exchange 65 Mile End Hospital Bancroft Road 5 Royal Foundation of Saint Butcher Row 59 Wapping Station Wapping High Street Katharine 42 Guoman Tower Hotel Saint Katharine’s Way 5 King David Lane Cable Street/The Highway John Orwell Sports Centre Tench Street 27 5 English Martyrs Club Chamber Street News International Pennington Street 26 5 Travelodge Aldgate East Chamber Street 25 Wiltons Music Hall Graces Alley Hotel 25 Whitechapel Art Gallery Whitechapel High Street 5 Albert Gardens Commercial Road 24 Prospect of Whitby PH Wapping Wall 5 Shoreditch House Club Ebor Street 22 Hawksmoor Restaurant E1 Commercial Street 5 Water Poet Restaurant Folgate Street 22 Poppies Fish & Chips Hanbury Street 5 Barcelona Tapas Bar & Middlesex Street 19 Shadwell Station Cable Street Restaurant 17 Allen Gardens Pedley Street/Buxton Street 5 Marco Pierre White's Steak & Middlesex Street/East India House 17 Bedford House E1 Quaker Street Alehouse Wapping High Street Saint Katharine’s Way/Garnet Street 15 Drunken Monkey Bar Shoreditch High Street 5 Light Bar E1 Shoreditch High Street 13 Hollywood Lofts Quaker Street 5 Pegasus House E1 White Horse Lane 12 Stepney Green Station Mile End Road 5 Pensions Management Artillery Lane 12 Spital Square Norton Folgate 4 Institute 12 Kapok Tree Restaurant Osborn Street -

Weekly List & Decisions

Planning Weekly List & Decisions Appeals (Received/Determined) and Planning Applications & Notifications (Validated/Determined) Week Ending 05/06/2020 The attached list contains Planning and related applications being considered by the Council, acting as the Local Planning Authority. Details have been entered on the Statutory Register of Applications. Online application details and associated documents can be viewed via Public Access from the Lambeth Planning Internet site, https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/planning-and-building- control/planning-applications/search-planning-applications. A facility is also provided to comment on applications pending consideration. We recommend that you submit comments online. You will be automatically provided with a receipt for your correspondence, be able to track and monitor the progress of each application and, check the 21 day consultation deadline. Under the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any comments made are open to inspection by the public and in the event of an Appeal will be referred to the Planning Inspectorate. Confidential comments cannot be taken into account in determining an application. Application Descriptions The letters at the end of each reference indicate the type of application being considered. ADV = Advertisement Application P3J = Prior Approval Retail/Betting/Payday Loan to C3 CON = Conservation Area Consent P3N = Prior Approval Specified Sui Generis uses to C3 CLLB = Certificate of Lawfulness Listed Building P3O = Prior Approval Office to Residential DET = Approval -

Elephant & Castle Equality Impact Assessment

Bakerloo line extension Outline Equality Impact Assessment: Elephant and Castle Station October 2019 F1457 A1 Equality Impact Assessment (EqIA) form N.B: the completed form should be emailed to the Diversity and Inclusion team Project * Bakerloo Line Extension Programme Elephant and Castle Station outline EqIA Strategy Po licy* Document Version Date Summary of History changes 0.1 20/09/19 First draft 0.2 04/10/19 Second draft * Delete as appropriate (the Accountable person should always be at least one management level higher than the Responsible person). Project Related Doc No. Document title Relevant Section(s) Documents of this Document Printed copies of this document are uncontrolled. Page 1 of 44 To be used in conjunction with: G1060 Title: Equality Impact Assessment (EqIA) form Document No.: F1457 Issue No.: A1 Step 1: Clarifying Aims Q1. Outline the aims/objectives/scope of this piece of work Introduction AECOM was commissioned by Transport for London (TfL) to undertake an Equality Impact Assessment (EqIA) for the Bakerloo Line Extension scheme, hereafter referred to as the ‘proposed scheme’. An EqIA is an assessment of the potential impacts of a proposed scheme on particular communities or Protected Characteristic Groups (PCGs) and supports TfL’s Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) requirement. This EqIA is one of nine which study the preferred station, work site and ventilation shaft locations along the Bakerloo line extension (as shown in Figure 1) as well as the other worksite options considered. These EqIAs work within the Mayor’s Transport Strategy, encouraging the Healthy Street Approach to prioritise human health and experience in planning the city, and changing London’s transport mix to work better for everyone.1 This is an outline EqIA (hereafter referred to as EqIA), which introduces the type of impacts which may be experienced at each station or work site. -

Kennington Conservation Area Statement 2012 Conservation Area

KenningtonKennington Conservation Area Statement 2012 Conservation Area Conservation Area Statement March 2012 Kennington Conservation Area Statement 2012 2 Kennington Conservation Area Statement 2012 CONTENTS PAGE CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT AND BOUNDARY MAPS 4 INTRODUCTION 6 1. PLANNING POLICY FRAMEWORK 7 2. CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 9 Geology 9 Archaeology 9 Origins and Historic Development 9 Spatial Analysis and Urban Quality 12 Landscape Framework 26 Public Realm 27 Activity and Uses 27 Architecture 27 Building Materials and Details 30 Boundary treatments 36 Advertisements 38 Garages 38 Refuse Stores 39 Listed Buildings 39 Building Contribution 39 Gardens and Spaces 39 Noteworthy Views 40 Capacity for Change 41 Appraisal Conclusion 41 3. GUIDANCE 42 Alterations to Existing Properties 42 New Buildings 45 Shopfronts 46 New Uses 46 Plant and Equipment 47 Boundary Treatments 47 Gardens and Trees 48 Advertisement Hoardings 48 Sustainability 49 4. MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS 50 Boundary Review 50 Planning Controls 50 Signage and Advertisements 50 Highways and Street Works 50 Trees 51 Enhancement Opportunities 51 Listed Buildings 52 Management Conclusion 53 5. CONTACTS 54 6. SOURCES 56 7. GLOSSARY 57 APPENDIX 1 Positive contribution 60 APPENDIX 2 Neutral contribution 70 APPENDIX 3 Statutory listed buildings 71 APPENDIX 4 Locally listed buildings 73 3 Kennington Conservation Area Statement 2012 CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT 4 Kennington Conservation Area Statement 2012 CONSERVATION AREA BOUNDARY The maps in this publication are based upon Ordnance Survey material with permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecu- tion or civil proceedings. -

Land to the East of Montford Place, Kennington, London, SE11

ADDRESS: Land To The East Of Montford Place, Kennington, London, SE11 5DE Application Number: 20/01086/FUL Case Officer: Magdalena Kotyza Ward: Oval Date Received: 20.03.2020 Proposal: Redevelopment of the site including the demolition of all existing buildings and structures, and erection of 2 linked buildings ranging from 6 to 11 storeys to provide a mixed use scheme comprising light industrial employment floorspace (Class B1c) with ancillary co-working/café space and residential units (Class C3) together with hard and soft landscaping and other associated works. This application is a DEPARTURE APPLICATION: The proposed development is a departure from Policy ED1 (Key Industrial and Business Areas (KIBAs) and Policy Q26(a)(ii) (Tall Buildings) of the Lambeth Local Plan (2015). Applicant: Connected Living London Agent: Mr Nick Green, Savills (Montford Place) Limited RECOMMENDATION 1. Resolve to grant conditional planning permission subject to the completion of an agreement under Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) containing the planning obligations listed in this report and any direction as may be received following further referral to the Mayor of London. 2. Agree to delegate authority to the Director of Planning, Transport and Sustainability to: a. Finalise the recommended conditions as set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes; and b. Negotiate, agree and finalise the planning obligations as set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes pursuant to Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended). 3. In the event that the committee resolves to refuse planning permission and there is a subsequent appeal, delegated authority is given to the Director of Planning, Transport and Sustainability, having regard to the heads of terms set out in this report, addendums and/or PAC minutes, to negotiate and complete a document containing obligations pursuant to Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (as amended) in order to meet the requirement of the Planning Inspector.