Georgy Smirnov the ARCHITECTURAL IMAGE OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Prerequisites of the Development of Applied Sciences in Russia in the 17Th – 18Th Centuries

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 2020 13(7): 1207-1215 DOI: 10.17516/1997-1370-0635 УДК 378.09 Prerequisites of the Development of Applied Sciences in Russia in the 17th – 18th Centuries. The First Attempts to Train Mechanics and Engineers in the 18th Century Margarita M. Voroninaa, Alexander V. Soldatovb and Petr V. Velikorussov*c aEmperor Alexander I St. Petersburg State Transport University Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation bSaint-Petersburg State Marine Technical University Saint-Petersburg, Russian Federation cIrkutsk National Research Technical University Irkutsk, Russian Federation Received 04.04.2019, received in revised form 04.06.2020, accepted 06.07.2020 Abstract. The article describes the directions of the development of applied mechanics in Russia in the 17th – 18th centuries and focuses on the first attempts to train specialists in these areas. These are the construction of roads, bridges, fortification and hydraulic engineering constructions, practical ballistics. Water and land means of communications are being improved, the industries that served the army and the fleet are developing, and the first attempts are being made to educate mechanics and technicians. Educational institutions are being opened, in which elements of mechanics are beginning to be taught. However, mechanics occupies an auxiliary position in relation to technology. Keywords: construction and applied mechanics, training, 18th century, Saint-Petersburg Academy of Science. Research area: history. Citation: Voronina, М.М., Soldatov, A.V., Velikorussov, P.V. (2020). Prerequisites of the development of applied sciences in Russia in the 17th – 18th centuries. The first attempts to train mechanics and engineers in the 18th century. J. -

Spring Newsletter

Spring 2019 iwcmoscow.ru Newsletter 1 1 Int ernat ional Wom en's Club of Moscow iw cm oscow.ru TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Letter from the Pr esident 04 Concer t for Char ity 08 Inter national Women's Evening 10 On the Cover : Tsar itsyno 12 In Memor y: Connie Meyer 13 IWC Char ities Fund 16 Coffee Mor nings 17 Inter est Group Spotlight 18 Meet & Gr eet 22 IWC on Social Media 23 Contacts 2 2 Letter from the Pr esident Dear and lovely m em bers of our Club, We are coming to the end of a busy year, where we met many new, interesting people, who then became very close to us. Our Club gives us the chance to learn about new cultures and opens up new horizons. In the past year, IWC held two very successful and large-scale events to raise funds for charities. As you know, these events were the Winter Bazaar and the Charity Concert. In 2018-2019, we supported over 25 charity projects. You can find a listing of the projects along with a description of the ways in which we helped this year on pages 14-15. On the eve of summer, let me wish you all a good holiday and unforgettable new memories. Thank you for being with us. We are working to continue to make progress and trying to make you happy with new and interesting events. Love and appreciation to all of you! Sincerely, Mery Toganyan President of the International Women's Club Spouse of the Armenian Ambassador to the Russian Federation 3 3 Concer t for Char ity On Monday, May 20, the International Women's Club of Moscow together with the Association of Winners of the International Tchaikovsky Competition presented a Charity Concert dedicated to the 40th anniversary of the Club. -

Expert Meeting of the Representatives of the Tourism Authorities of the Brics Countries

DELEGATE HANDBOOK EXPERT MEETING OF THE REPRESENTATIVES OF THE TOURISM AUTHORITIES OF THE BRICS COUNTRIES MOSCOW, THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION 18 MARCH 2020 CONTENTS 1. The Operational Headquarters Contact Information ....................................... 3 2. Meeting Dates and Venue ............................................................. 3 3. Meeting Programme .................................................................. 3 4. Meeting Format ......................................................................4 5. Access to the Meeting Venue ..........................................................4 5.1. ID Badges ......................................................................4 5.2. Summary of Access Procedures ....................................................4 5.3. Lost Badges ....................................................................4 6. Working language ....................................................................4 7. Transport ...........................................................................5 7.1. Aeroexpress ....................................................................5 7.2. Public Transport and Taxis ........................................................6 8. Meeting Facilities ....................................................................8 8.1. Information Desk ................................................................8 8.2. Wi-Fi ...........................................................................8 9. General Information ..................................................................8 -

Olga Antsygina, MD, MPH [email protected] | 613 532 3840 EDUCATION

Olga Antsygina, MD, MPH [email protected] | 613 532 3840 EDUCATION 01.2020 – current Ph.D. student (Health Sciences) Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada Thesis title: “Relationships among body weight status, physical and cognitive development, and nutritional indicators of four-year-old children sampled in Russia, Mongolia, Singapore, Tanzania, and Canada”. Supervisors: Dr. Tremblay M.T.; Dr. Peters P. 08.2013 – 08.2015 Master of Public Health (MPH) with the certificate of Applied biostatistics The University of South Florida, Tampa, USA Thesis: “Longitudinal study of childhood exposure to violence on antisocial personality disorder symptoms score among adults aged from 18 to 40 years”. GPA 3.42 out of 4 Fully sponsored by the Fulbright foreign student program and USF out-of-state tuition award. 09.2008 – 08.2010 Certified General Medical Practitioner of the Russian Federation Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia Clinical residency in general practice (internal medicine); Faculty of Fundamental Medicine 09.2002 – 06.2008 Doctor of Medicine (MD) I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, Moscow, Russia Faculty of Research and Teaching Staff Training; General Medicine (4th, 5th and 6th years of training); GPA 4.5 out of 5 (equivalent to 3.6 out of 4) Thesis: “The investigation of psychophysiological characteristics of junior schoolchildren with and without ADHD symptoms” Izhevsk State Medical Academy, Izhevsk, Russia Medical Faculty; General Medicine (1st, 2nd and 3rd years of training) PUBLICATIONS and PRESENTATIONS B. Idrisov, O. Elizarova, O. Antsygina. Presentation “Pioneering Digital Health in Russia: A Case of Panacea Cloud, Behavioral Modification Program for Overweight People”. Mobile and Electronic Health Affinity Research Collaborative Seminar, Boston University, February 5th, 2019 https://sites.bu.edu/me-arc/news/ Moschovis PP, Wiens MO, Arlington L, Antsygina O, Hayden D, Dzik W, Kiwanuka JP, Christiani DC, Hibberd PL. -

ШОС Справочник Делегата МСК 20-23.08 ENG.Indd

DELEGATE HANDBOOK MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF NATIONAL COORDINATORS OF THE SCO MEMBER STATES MOSCOW, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 20–23 AUGUST, 2019 CONTENTS 1. Meeting dates and venue . .3 2. Meeting programme . .3 3. Access to meeting . 4 3.1. ID Badges . .4 3.2. Summary of Access Procedures . .4 3.3. Lost Badges . .4 4. Meeting facilities . 4 4.1. SCO Information Desk . .4 4.2. Wi-Fi . .4 5. General information . 4 5.1. Weather . .4 5.2. Time . .4 5.3. Electricity . .4 5.4. Smoking . .5 5.5. Credit cards . .5 5.6. Currency and ATMs . .5 5.7. Mobile phone information . .5 5.8. Pharmacies . .5 5.9. Souvenir shops . .5 5.10. Shoe repairs . .6 6. Useful telephone numbers . 6 7. City information . 6 8. Restaurants . 9 9. Venue plan . 9 MOSCOW | 20–23 AUGUST 2 1. MEETING DATES AND VENUE The meeting of the Council of National Coordinators of the SCO Member States will be held on 20–23 August 2019 in Moscow. Meeting venue: THE RITZ-CARLTON HOTEL, MOSCOW 3, Tverskaya str., Moscow, 125009 www.ritzcarlton.com/ru/hotels/europe/moscow 2. MEETING PROGRAMME 20 August, Mon The meeting of the Council of National Coordinators of the SCO 09:30–18:00 Member States 09:00 Delegates arrival 11:00–11:15 Coff ee-break 13:00–14:30 Lunch 16:00–16:20 Coff ee-break 21 August, Tue The meeting of the Council of National Coordinators of the SCO 09:30–18:00 Member States 09:00 Delegates arrival 11:00–11:15 Coff ee-break 13:00–14:30 Lunch 16:00–16:20 Coff ee-break 18:30 Reception on behalf of the Special Presidential Envoy for SCO Aff airs in honourмof the participants in the Council of National Coordinators meeting Cultural programme 22 August, Wed The meeting of the Council of National Coordinators of the SCO 09:30– 18:00 Member States 09:00 Delegates arrival 11:00–11:15 Coff ee-break 13:00–14:30 Lunch 16:00–16:15 Coff ee-break 23 August, Thu The meeting of the Council of National Coordinators of the SCO 09:30– 18:00 Member States 09:00 Delegates arrival 11:00–11:15 Coff ee-break 13:00–14:30 Lunch 16:00–16:15 Coff ee-break 16:15–18:00 Signing of the fi nal Protocol MOSCOW | 20–23 AUGUST 3 3. -

Dialogue of the Seas No.5, 2012

Black Sea-Caspian Sea: strategy for a wider region Cultural heritage and barbarians of the XXIst century No. 5, 2012 BSEC’s th 0anniversary: Alexander 2mutual trust, Dugin: common priorities formula Azerbaijan and Europe’s to the future energy security of Eurasia It’s raining with Olympic medals VlaDE DivaC: THE LEGEND GOES ON SERBIA LOOKS IN TOMORROW BorodinoBorodino Panorama Panorama The Adriatic landscape - the background of the “summit” of the Black Sea-Caspian Sea Fund BSCSIFCHRONICLE - is the direct proof of the Fund’s broadening BSCSIFCHRONICLE PHOTO: VYacheslav SAMOSHKIN outward the region The “Maestral” Hotel will be remembered as the place where important decisions were made impersonated by the Ambassador Livio Hürzeler - joining our ranks. This suggests that the values targeted by the statute and the strategy of the Fund, and, foremost, the promotion LE of dialogue, peace and harmony, are in tune with the European ones, but also in tune with the Eurasian values, because we also accepted an Iranian IC citizen as a full BSCSIF member. Today, our Fund is getting wider, indeed. Where did our meeting take place? At the Adriatic Sea, in Mon- tenegro, and this is not a part of the Black Sea- Caspian Sea region. The Assembly’s attendees paid a moment-of-silence According to the second pivotal tribute to the tragically deceased friend - BSCSIF Vice- decision adopted, there will be estab- President, Prof. Tamaz Beradze A strategy lished within the Fund a Center for Strategic Research of the Black Sea – Caspian Sea region. It was a very wise idea - to gather under one roof for a wider region scholars, professionals and academi- cians from most of our countries. -

"Москва". Система Времен Английского Глагола Present, Past, Future (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous)

Семестр 1 Модуль 2 Тема 7. Страноведение. Устная тема "Москва". Система времен английского глагола Present, Past, Future (Simple, Continuous, Perfect, Perfect Continuous). Неправильные глаголы. 1. Прочтите и переведите следующий текст. Moscow Moscow is the capital of Russia, its administrative, economic, political and educational centre. It is located on the river Moskva in the western region of Russia. It is one of Russia's major cities with the population of over 9 million people. Its total area is about 900 thousand square kilometers. Moscow is a unique city, its architecture combines the features of both Oriental and Western cultures. Today we are the witnesses of a new stage in Moscow’s life. Here more than anywhere else one can feel the atmosphere of all those changes which draw the attention of the whole world. The city was founded By Prince Yuri Dolgorukiy and was first mentioned in the chronicles in 1147. At that time it was a small frontier settlement. By the 15th century Moscow had grown into a wealthy city. In the 16th century, under Ivan the Terrible, Moscow became the capital of the state of Muscovy. In the 18th century Peter the Great transferred the capital to St. Petersburg, but Moscow remained the heart of Russia. That is why it became the main target of Napoleon's attack in 1812. During the war of 1812 three quarters of the city were destroyed by fire, but By the middle of the 19th century Moscow was completely rebuilt. The present-day Moscow is the seat of the government of the Russian Federation. -

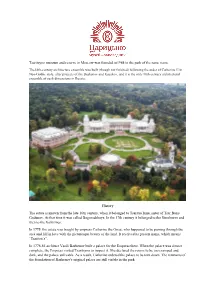

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07. -

ON the ROAD City Moscow

a a a s r Hotel Hilton i a y t k li s D vo o u M t o e l li k va a t y u u uc ry k o 2-ya Brestskaya ulitsa e Ragout a a h p r k e a i y e h s e ulitsa Fadeeva t p s ga a v a s 4-ya 11Tverskaya Yamskaya ulitsa ele p k p M D o y i s e 3 Sad r r a tsa ova k s e s uli p - naya Samotechnaya ulitsa ya NII Skoroy Pomoshchi a it ya tech Sadovaya -S s S u l 1-ya Brestskaya ulitsa ovaya Samo uk ’ kor Sad ha l p lo u 1 rev Sklifosovskogo e S Kazansky s t n k ulitsa Chayanova 1 ka y a ya p a az T u s T v lit y vokzal sa o h t e a i r K n l s lok h iy u k y s B ’ p a l - Kalanchevskaya ulitsa l a y reu eu e o e r 1 o r a p A. A. Chernikhov Design e Dokuchaev pereulok y 6 l iy e n B a Y y ’ u e s am h p and Architecture Studio l k z o u h r Sukharevskaya s O v k o s v k o y o a h y y K k a i h a u L c li r Ryazanskiy proezd ts a e n Novoryazanskaya ulitsa 1-ya 11Tverskaya Yamskaya ulitsa s t a t la li n u a a iy o y l a K n Tsventoy bul’var u l’ p Sadovaya-Spasskaya ulitsa fa e m e r iu ultisa Petrovka r e a r e T p 52 k r Bol’shaya Gruzinskaya ulitsa 53 ya u n a a ulitsa Malaya Dmitrovka k v l iy o o e o lok v n l d reu ’ n pe k t Mayakovskaya eu Sa Maliy Karetniy l a e m r u s r 2-ya Brestskaya ulitsa pe b S iy V n y y o a o r s n he o t ulitsa Mashi poryvaevoy z i t t l ru ni pereulok 2-ya Brestskaya ulitsa etniy e O dniy Kar k u k Sad e v ereulo Orlikov pereulok o r arevskiy p Vasilyevskaya ulitsa S s kh Daev pereulok v T Bol’shoy Su 64 Ermitazh T o s Krasnovorotskiy proezd s v Mosproekt-2 k e i Tishinskaya ulitsa Yuliusa Fuchika y t p Pushkinskaya -

Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920S-1930S

“Soviet Architecture and its National Faces ”: Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920s-1930s By Anna Pronina Submitted to Central European University Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Comparative History Supervisor: Professor Charles Shaw Second Reader: Professor Marsha Siefert CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2020 Copyright Notice Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection ii Abstract The thesis “Soviet Architecture and its National Faces”: Soviet Architecture in Central Asia, 1920s-1930s is devoted to the various ways Soviet Central Asian architecture was imagined during the 1920s and the 1930s. Focusing on the discourses produced by different actors: architects, Soviet officials, and restorers, it examines their perception of Central Asia and the goals of Soviet architecture in the region. By taking into account the interdependence of national and architectural history, it shows a shift in perception from the united cultural region to a set of national republics with their own histories and traditions. The thesis proves that national architecture of the Soviet Union, and in Central Asia in particular, was a visible issue in public architectural discussions. Therefore, architecture played a significant role in forging national cultures in Soviet Central Asia. -

Great Britain, Its Political, Economic and Commercial Centre

Федеральное агентство по образованию Государственное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «Рязанский государственный университет имени С.А. Есенина» Л.В. Колотилова СБОРНИК ТЕКСТОВ НА АНГЛИЙСКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ по специальности «География. Туризм» Рязань 2007 ББК 81.432.1–923 К61 Печатается по решению редакционно-издательского совета Государственно- го образовательного учреждения высшего профессионального образова- ния «Рязанский государственный университет имени С.А. Есенина» в со- ответствии с планом изданий на 2007 год. Научный редактор Е.С. Устинова, канд. пед. наук, доц. Рецензент И.М. Шеина, канд. филол. наук, доц. Колотилова, Л.В. К61 Сборник текстов на английском языке по специальности «Гео- графия. Туризм» / Л.В. Колотилова ; под ред Н.С. Колотиловой ; Ряз. гос. ун-т им. С.А. Есенина. — Рязань, 2007. — 32 с. В сборнике содержатся тексты о различных странах мира, горо- дах России, а также музеях России. Адресовано студентам по специальности «География. Туризм». ББК 81.432.1–923 © Л.В. Колотилова 2 © Государственное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «Рязанский государственный университет имени C.А. Есенина», 2007 COUNTRIES THE HISTORY OF THE BRITISH ISLES BritaiN is an island, and Britain's history has been closely coN- nected with the sea. About 2000 ВС iN the Bronze Age, people in BritaiN built Stone- henge. It was a temple for their god, the Sun. Around 700 ВС the Celts travelled to BritaiN who settled iN southerN England. They are the ancestors of many people iN Scotland, Wales, and Ireland today. They came from central Europe. They were highly successful farmers, they knew how to work with iron, used bronze. They were famous artists, knowN for their sophisticated designs, which are found iN the elaborate jewellery, decorated crosses and illuminated manuscripts.