Melin 28 Draft Final V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clonc 321.Pdf

Rhifyn 321 - 60c www.clonc.co.uk - Yn aelod o Fforwm Papurau Bro Ceredigion Mawrth 2014 Papur Bro ardal plwyfi: Cellan, Llanbedr Pont Steffan, Llanbedr Wledig, Llanfair Clydogau, Llangybi, Llanllwni, Llanwenog, Llanwnnen, Llanybydder, Llanycrwys ac Uwch Gaeo a Phencarreg Llwyddiant Cadwyn Côr Cwmann i Glwb Cyfrinachau yn dathlu Llanllwni arall 50 mlynedd Tudalen 5 Tudalen 13 Tudalen 22 Llwyddiant ein hieuenctid a dathlu Gŵyl Ddewi Enillydd y Gadair oedd Llion Thomas, Dulais ac yntau Enillydd y Goron oedd Cerian Jenkins, gyda Cari Davies (chwith) yn hefyd oedd yn drydydd. Yn ail roedd Gethin Morgan, ail a Julianna Barker yn drydydd. Creuddyn ac hefyd yn ennill y Darian ar gyfer y marciau uchaf am y gwaith llwyfan a Chwpan am y marciau uchaf yn yr adran gwaith cartref. Gweler y gerdd ar dud 15. Owain Davies ar y dde ac Ifor Jones ar y chwith a gafodd lwyddiant yng nghystadleuaeth Hanner Awr o Adloniant Sir Gâr fel actorion dan 18 oed. Cafodd Owain yr ail wobr ac Ifor yn 3ydd. Mae’r ddau yn aelodau gweithgar o G.Ff.I. Llanllwni. Rhai o blant Cyfnod Sylfaen Ysgol Bro Pedr yn dathlu Gŵyl Ddewi. Eisteddfod Ysgol Bro Pedr Adroddiad llawn ar dudalen 8 a 9 A ydych chi’n chwilio am y ffordd orau i deithio o amgylch eich ardal? n Eisiau cyrraedd y gwaith a llefydd hyfforddiant? n Eisiau ymweld â theulu a ffrindiau? BWCABUS n Angen cael gofal iechyd? n Chwant mynd ar daith am y diwrnod? 618 Talsarn – Llanbedr Pont Steffan Bwcabus yw’r ateb! Drwy Bwlchyllan – Silian Bwcabus yw’r ateb! Dydd Mawrth yn unig Dydd Llun – Dydd Sadwrn 7am – 7pm Talsarn, gyferbyn Maes Aeron 9.25 am Mae Bwcabus yn galluogi pobl o unrhyw oed i deithio rhwng trefi Bwlch-llan, Capel 9.32 am a phentrefi lleol. -

Local Development Plan Written Statement

Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 2007-2022 BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN AS ADOPTED BY THE BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY 17TH DECEMBER 2013 i Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 2007-2022 ii Brecon Beacons National Park Authority Local Development Plan 2007-2022 Contents 1 Introduction...................................................................................................................1 1.1 The Character of the Plan Area ..................................................................................1 1.2 How the Plan has been Prepared ..............................................................................................................1 1.3 The State of the Park: The Issues.............................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 2: THE VISION & OBJECTIVES FOR THE BRECON BEACONS NATIONAL PARK...................................................................................................................5 2.1 The National Park Management Plan Vision ...........................................................................................5 2.2 LDP Vision.......................................................................................................................................................6 2.3 Local Development Plan (LDP) Objectives.............................................................................................8 2.4 Environmental Capacity -

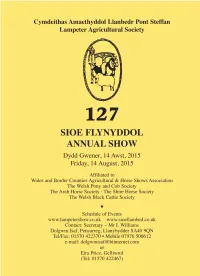

2015 Schedule.Pdf

CYMDEITHAS AMAETHYDDOL LLANBEDR PONT STEFFAN LAMPETER AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY Llywyddion/Presidents — Mr Graham Bowen, Delyn-Aur, Llanwnen Is-Lywydd/Vice-President — Mr & Mrs Arwyn Davies, Pentre Farm, Llanfair Milfeddygon Anrhydeddus/Hon. Veterinary Surgeons — Davies & Potter Ltd., Veterinary Surgeons, 18 –20 Bridge Street, Lampeter Meddygon Anrhydeddus/Hon. Medical Officers — Lampeter Medical Practice, Taliesin Surgery Announcers — Mr David Harries, Mr Andrew Jones, Mr Andrew Morgan, Mr Gwynne Davies SIOE FLYNYDDOL/ ANNUAL SHOW to be held at Pontfaen fields, Lampeter SA48 7JN By kind permission of / drwy ganiatâd Mr & Mrs A. Hughes, Cwmhendryd Gwener/Friday, Awst/August 14, 2015 Mynediad/Admission : £8.00; Children under 14 £2.00 Enquiries to: I. Williams (01570) 422370 or Eira Price (01570) 422467 Schedules available on our Show website: www.lampetershow.co.uk • www.sioellambed.co.uk or from the Secretary – Please include a S.A.E. for £1.26 (1st class); £1.19 (2nd class) Hog Roast from 6 p.m. 1 CYMDEITHAS AMAETHYDDOL LLANBEDR PONT STEFFAN LAMPETER AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY SWYDDOGION A PHWYLLGOR Y SIOE/ SHOW OFFICIALS AND COMMITTEE Cadeirydd/Chairman — Miss Eira Price, Gelliwrol, Cwmann Is-Gadeirydd/Vice-Chairman — Miss Hâf Hughes, Cwmere, Felinfach Ysgrifenydd/Secretary— Mr I. Williams, Dolgwm Isaf, Pencarreg Trysorydd/Treasurer— Mr R. Jarman Trysorydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Treasurer— Mr Bedwyr Davies (Lloyds TSB) AELODAU OES ANRHYDEDDUS/HONORARY LIFE MEMBERS Mr John P. Davies, Bryn Castell, Lampeter; Mr T. E. Price, Gelliwrol, Cwmann; Mr Andrew Jones, Cwmgwyn, Lampeter; Mr A. R. Evans, Maes yr Adwy, Silian; Mrs Gwen Jones, Gelliddewi Uchaf, Cwmann; Mr Gwynfor Lewis, Bronwydd, Lampeter; Mr Aeron Hughes, Cwmhendryd, Lampeter; Mrs Gwen Davies, Llys Aeron, Llanwnen; Mr Ronnie Jones, 14 Penbryn, Lampeter. -

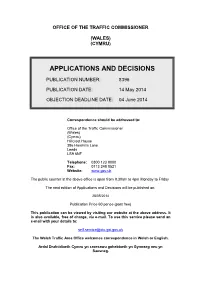

Applications and Decisions

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WALES) (CYMRU) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 8396 PUBLICATION DATE: 14 May 2014 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 04 June 2014 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Wales) (Cymru) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 28/05/2014 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] The Welsh Traffic Area Office welcomes correspondence in Welsh or English. Ardal Drafnidiaeth Cymru yn croesawu gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg neu yn Saesneg. APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Wales) (Cymru) 38 George Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 1PL The public counter in Birmingham is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. -

Fan Barrow Evaluation Excavation Interim Report 2010

EVALUATION EXCAVATION AT FAN BARROW, TALSARN, CEREDIGION 2010 INTERIM REPORT Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2010/ 61 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO . 100252 Tachwedd 2010 November 2010 EVALUATION EXCAVATION AT FAN BARROW, TALSARN, CEREDIGION 2010 INTERIM REPORT Gan / By Duncan Schlee Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. The Dyfed Archaeological Trust Ltd can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. YMDDIRIEDOLAETH ARCHAEOLEGOL DYFED CYF DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST LIMITED Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www. dyfedarchaeology .org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. -

Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth (Solicitors) Records, (GB 0210 ROBEVS) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 04, 2017 Printed: May 04, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/roberts-evans-aberystwyth-solicitors- records-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/roberts-evans-aberystwyth-solicitors-records-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Roberts & Evans, Aberystwyth (Solicitors) Records, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 5 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 5 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................ -

Cludiant Ysgol School Transport Cwmni Bws Côd Ffordd Bws / Bus Route Bus Company Code Bysiau Sir Caerfyrddin / Carmarthenshire Buses

Cludiant Ysgol School Transport Cwmni Bws Côd Ffordd Bws / Bus Route Bus Company Code Bysiau Sir Caerfyrddin / Carmarthenshire Buses Hermon (Penwaun), Maudlands, Five Roads, Ty-coch, Rhos, Saron (Trewern), Llangeler to Lewis Rhydlewis E1 Ysgol Gyfun Emlyn. Lewis Rhydlewis E2 Maudland (Maldini Lodge), Tanglwst (shelter), Black Oak, Capel Iwan to Ysgol Gyfun Emlyn Cwmpengraig (Square), Drefach (Premier Stores), Pentrecgal (Green Park) to Ysgol Gyfun Brodyr Richards E3 Emlyn Bancyffordd (square), Dolgran, Pencader (Square), Llanfihangel-ar-arth (Cross Inn), Pontweli Lewis Rhydlewis E4 (Wilkes Head), Heol Pentrecwrt (Maesymeillion) to Ysgol Gyfun Emlyn Lewis Rhydlewis E6 Cwm Morgan (square), Pont Wedwst, Cwmcych, Danyrhelyg to Ysgol Gyfun Emlyn Lewis Rhydlewis E8 Penboyr (old vicarage), Five Roads. [Pupils change to E1] Lewis Rhydlewis E9 New Inn (shelter), Pencader (square). [Pupils change to E4] Brodyr Richards E11 Pentrecwrt (Square), Waungilwen (Shelter), to Ysgol Gyfun Emlyn Bysiau Ceredigion / Ceredigion Buses Morris Travel / Cardigan (Tesco), Finch Square, Llechryd, Llandygwydd Turn, Cenarth (Post Office) to Ysgol YD01 / 460 Brodyr Richards Gyfun Emlyn Cerbydau Capel Tygwydd, Ponthirwaun, Neuadd Cross, Beulah, Bryngwyn, Cwmcou to Ysgol Gyfun YD04 Cenarth Emlyn Cerbydau Sarnau, Glynarthen, Betws Ifan, Brongest, Troed yr Aur, Penrhiwpal, Ffostrasol. YD07 Cenarth [Pupils transfer to YD09] Cerbydau Sarnau, Glynarthen, Betws Ifan, Brongest, Salem Chapel, Penrhiwpal, YD08 Cenarth Coedybryn, Aberbanc, [Connect to YD03] Henllan to Ysgol Gyfun -

11Th WELSH ORCHID FESTIVAL 1St & 2Nd September 2018 to Be Held at the National Botanic Garden of Wales Llanarthne, Carmarthenshire, Wales SA32 8HN

The Post Your Local Community Magazine Over 4800 copies Number 271 August 2018 Published by PostDatum, 24 Stone Street, Llandovery, Carms SA20 0JP Tel: 01550 721225 THE ORCHID STUDY GROUP PRESENTS ITS 11TH WELSH ORCHID FESTIVAL 1ST & 2ND SEPTEMBER 2018 To be held at the National Botanic Garden of Wales Llanarthne, Carmarthenshire, Wales SA32 8HN The Welsh Orchid Festival welcomes the return of some Festival opening hours: Saturday: 10.00am – 6.00pm of your favourite orchid nurseries, as well as new traders Sunday: 10.00am – 4.00pm with a dazzling array of rare orchid species and hybrids Normal admission fees to the Garden apply. Entry into for sale, and some of their finest and most spectacular the Orchid Marquee, talks and demonstrations is free. blooms. For a full list of attendees and programme of talks, There will also be stalls selling carnivorous plants, visit the OSG website: www.orchidstudygroup.org.uk orchid companion plants, botanical paintings and other (which will be updated regularly), or telephone the works of art, as well as orchid and general plant books. Secretary on: 01269 498002. Regular talks and demonstrations on all aspects of For information on the National orchid cultivation for both beginner and experienced Botanic Garden of Wales, please visit grower will be held throughout the weekend, as well as their website: www.gardenofwales.org. a workshop on orchid micropropagation. uk or telephone: 01558 667149. FOR ALL YOUR LOCAL NEWS & BUSINESS SERVICES ALL ABOUT The Post COPY DATE for next issue: 15th August 2018 Next issue distributed: 30th August 2018 The Post Future Copy Dates October ....................................14th September November .....................................16th October December/January 2019 ..........16th November 07/18(3) Opinions expressed in The Post are not necessarily those of the publisher, editor or designer and the magazine is in no way liable for those opinions. -

Eisteddfod Y DDOLEN 2021

Eisteddfod y DDOLEN 2021 Pan nad oes unman i fynd, man a man ceisio cael pobl i gystadlu mewn Eisteddfod! Arferai papur bro Y DDOLEN gynnal Eisteddfod lenyddol yn flynyddol ond bu saib ers sawl blwyddyn. Roedd eleni yn teimlo gystal amser ac unrhywbryd i ail gynnau’r fflam! Aed ati i lunio casgliad o gystadlaethau amrywiol o limrig i goginio! Yn ogystal roedd modd ennill y gadair gyfforddus ddefnyddiol drwy gystadlu yn y stori neu gerdd ddigri. Braf iawn oedd derbyn deunydd o ardal y DDOLEN a thu hwnt, a diolch i bawb wnaeth gymryd yr amser i farddoni, ysgrifennu, coginio ac arlunio. Gobeithio i chi fwynhau yr heriau a osodwyd. Diolch i Ifan a Dilys Jones, Tregaron am feirniadu’r cystadlaethau agored, i Geoff a Bethan Davies, Rhydyfelin am feirniadu’r ysgrifennu creadigol i blant a phobl ifanc ac i Lizzi Spikes, Llanilar am feirniadu’r arlunio. Mae wedi bod yn bleser cyhoeddi’r deunydd buddugol yn Y DDOLEN yn ystod y misoedd diwethaf a gobeithio i’n darllenwyr fwynhau’r arlwy amrywiol. Edrychwn ymlaen at Eisteddfod 2022 a phwy a ŵyr, efallai gwnawn ni fentro i’r llwyfan tro nesaf! Limrig 1. Megan Richards, Brynderi, Aberaeron Gwelais yn ystod y cyfnod clo, 2. Megan Richards, Brynderi, Aberaeron Holl fywyd cefn gwlad yn dirywio, Capeli ar drai, 3. Aled Evans, Blaenwaun, Trisant Holl siopau yn cau Brawddeg A’r dafarn a’r ysgol yn brwydro. (1af, Megan Richards) 1. Gaenor Mai Jones, Hafod, Pentre’r Eglwys, Rhondda Cynon Taf 2. Megan Richards, Brynderi, Aberaeron 3. Carol Thomas-Harries, Yr Aelwyd, Blaenannerch Neges mewn potel 1. -

Llanfair Shop, Llanfair Clydogau, Lampeter SA48

Llanfair Shop, Llanfair Clydogau, Lampeter SA48 8LA Offers in the region of £389,500 • ** IDEAL LIFESTYLE OPPORTUNITY & GOOD INCOME POTENTIAL ** • Delightful Rural Village Location • Banks Of River Teifi & Views • Established Shop/P.O With 3 Bed House & 2 Bed Flat John Francis is a trading name of Countrywide Estate Agents, an appointed representative of Countrywide Principal Services Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, fittings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is verified by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also confirm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. EJ/WJ/62594/200318 Traditionally built of stone low level flush WC, pedestal walls lying under a slated roof wash hand basin, walk-in DESCRIPTION and benefiting from double airing cupboard, exposed ** SUPERB LIFESTYLE glazed windows and oil fired beams, radiator, window to OPPORTUNITY IN THE central heating system. -

Churchyards Visited in Ceredigion

LIST OF CHURCHYARDS VISITED IN CEREDIGION Recorders: PLACE CHURCH GRID REF Link to further information Tim Hills YEAR Aberystwyth St Michael SN58088161 No yews PW 2015 Borth St Matthew SN61178974 No yews PW 2015 Bwlch-llan - formerly St Cynllo SN57605860 Gazetteer - lost yew TH 2014 Nantcwnlle Capel Bangor St David SN65618013 Younger yews PW 2015 Cenarth St Llawddog SN27034150 Oldest yews in the Diocese of St Davids TH 2005 Ciliau Aeron St Michael SN50255813 Oldest yews in the Diocese of St Davids TH 2014 Clarach All Saints SN60338382 Younger yews PW 2015 Dihewyd St Vitalis SN48625599 Younger yews TH 2005 Paolo Eglwys Fach St Michael SN68579552 Gazetteer 2014 Bavaresco Arthur Gartheli unrecorded SN58595672 Gazetteer - lost yew O.Chater Arthur Hafod - Eglwys Newydd SN76857363 Gazetteer O.Chater Lampeter St Peter SN57554836 Gazetteer TH 2000 Llanafan St Afan SN68477214 Oldest yews in the Diocese of St Davids TH 2014 Llanbadarn Fawr Arthur St Padarn SN59908100 Gazetteer - lost yew (Aberystwyth) O.Chater Llancynfelyn St Cynfelyn SN64579218 Younger yews PW 2015 Llanddewi-Brefi St David 146/SN 664 553 Younger yews TH 2005 Llandre St Michael SN62308690 Oldest yews in the Diocese of St Davids TH 1999 Llanerchaeron St Non SN47726037 Gazetteer TH 2014 (Llanaeron) Llanfair Clydogau St Mary SN62435125 Oldest yews in the Diocese of St Davids TH 1999 Llanfihangel - y - St Michael SN66517604 Gazetteer TH 2014 Creuddyn Llangeitho St Ceitho SN62056009 Oldest yews in the Diocese of St Davids TH 1999 Llangoedmor St Cynllo SN19954580 Oldest yews in the Diocese -

Arwyn Evans Clipper Services Aeron Valley Tractors

Class 1 a - Level 4 Pony Club Area 18 Qualifier for Branch Teams Kindly Sponsored by: Class 1b - Level 4 Pony Club Area 18 Qualifier for Branch Indi- Arwyn Evans Clipper Services viduals SJ Max 1.05m. XC Max 1.00m. Sales, Servicing, Repairs, Safety Testing and Sharpening Dressage Test: Pony Club Intermediate Eventing Test 2015 Llanfair Fawr, Llanfair Clydogau, Lampeter Tel: 01570 493 205 Entry Fee: £50.00 per rider/horse combination Please send cheques with entries to: Class 2a - Level 3 Pony Club Area 18 Qualifier for Branch Teams Mr T Joynson, Brynllewelyn, Llanllwni, Pencader, Carms Class 2b – Level 3 Pony Club Area 18 Qualifier for Branch Indi- SA39 9ED viduals CHEQUES PAYABLE TO: THE PONY CLUB AREA 18 Entries Close Friday 24th July 2015 SJ 95cm Max. XC 90cm Max. Dressage Test: Pony Club Novice Eventing Test 2012 NO LATE ENTRIES WILL BE ACCEPTED Entry Fee: £50.00 Per rider/horse combination All entries to be sent via Branch DC/Centre Proprietor using the entry form provided, which will also be on the Area 18 Website. Start times available on Area 18 website from Thursday 30th July Class 3a – Level 2 Branch Junior Team Competition Class 3b – Level 2 Branch Junior Individual Competition or by Calling 01559 395237 between 7.30pm – 9.30pm SJ Max 85cm XC Max 80cm CONDITION OF ENTRY: Dressage Test: Pony Club C Level 2012 All participating Pony Club Branches are expected to provide a Entry Fee: £40.00 per rider/horse combination minimum of 2 volunteers to help on the day. Please include names Class 4a – Level 1 Branch Mini Team Competition and phone numbers of all the helpers on your Entry Form.