Yearbook of Muslims in Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim

2 | Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim Author Biography Justin Parrott has BAs in Physics, English from Otterbein University, MLIS from Kent State University, MRes in Islamic Studies in progress from University of Wales, and is currently Research Librarian for Middle East Studies at NYU in Abu Dhabi. Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2017. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Mindfulness in the Life of a Muslim Introduction In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful Modern life involves a daily bustle of noise, distraction, and information overload. Our senses are constantly stimulated from every direction to the point that a simple moment of quiet stillness seems impossible for some of us. This continuous agitation hinders us from getting the most out of each moment, subtracting from the quality of our prayers and our ability to remember Allah. We all know that we need more presence in prayer, more control over our wandering minds and desires. But what exactly can we do achieve this? How can we become more mindful in all aspects of our lives, spiritual and temporal? That is where the practice of exercising mindfulness, in the Islamic context of muraqabah, can help train our minds to become more disciplined and can thereby enhance our regular worship and daily activities. -

School of Humanities and Social Sciences Al-Ghazali's Integral

School of Humanities and Social Sciences Al-Ghazali’s Integral Epistemology: A Critical Analysis of The Jewels of the Quran A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Arab and Islamic Civilization in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Amani Elshimi 000-88-0001 under the supervision of Dr. Mohamed Serag Professor of Islamic Studies Thesis readers: Dr. Steffen Stelzer Professor of Philosophy, The American University in Cairo Dr. Aliaa Rafea Professor of Sociology, Ain Shams University; Founder of The Human Foundation NGO May 2017 Acknowledgements First and foremost, Alhamdulillah - my gratitude to God for the knowledge, love, light and faith. My deepest thanks go to my supervisor and readers, whose individual passions and critical guidance helped shape my research perspective, sustain my sanity and boost my confidence - Dr. Mohamed Serag, who first initiated me into the scholarship of al- Ghazali and engaged me in eye-opening theological debates, Dr. Steffen Stelzer, whose academic expertise and personal sufi practice inspired my curiosity and touched me in deep spiritual ways, and Dr. Aliaa Rafea, who, through her lectures and practices, emphasized how the depths of meaning in the Quran can contribute to human development in contemporary times. Throughout this adventure, my colleagues and friends have been equally supportive - Soha Helwa and Wafaa Wali, in particular, have joined me in bouncing ideas back and forth to refine perspective and sustain rigor. Sincere appreciation and love goes to my family - my dear husband and children, whose unswerving support all these years has helped me grow in ways I yearned for, and never dreamed possible; and my siblings who constantly engaged me in discussion and critical analysis. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

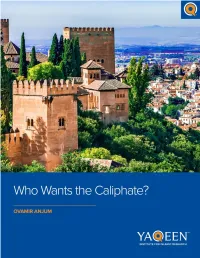

Who-Wants-The-Caliphate.Pdf

2 | Who Wants the Caliphate? Author Biography Dr. Ovamir Anjum is Imam Khattab Endowed Chair of Islamic Studies at the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, University of Toledo. He obtained his Ph.D. in Islamic history in the Department of History, University of Wisconsin-Madison. His work focuses on the nexus of theology, ethics, politics and law in Islam, with comparative interest in Western thought. His interests are united by a common theoretical focus on epistemology or views of intellect/reason in various domains of Islamic thought, ranging from politics (siyasa), law (fiqh), theology (kalam), falsafa (Islamic philosophy) and spirituality (Sufism, mysticism, and asceticism). Author of Politics, Law and Community in Islamic Thought: The Taymiyyan Moment (Cambridge University Press, 2012), Dr. Anjum has also translated a popular Islamic spiritual and theological classic, Madarij al-Salikin (Ranks of Divine Seekers) by Ibn al-Qayyim (d. 1351); the first two volumes to be published by Brill later this year. His current projects include a multi-volume survey of Islamic history and a monograph on Islamic political thought. Disclaimer: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in these papers and articles are strictly those of the authors. Furthermore, Yaqeen does not endorse any of the personal views of the authors on any platform. Our team is diverse on all fronts, allowing for constant, enriching dialogue that helps us produce high-quality research. Copyright © 2019. Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research 3 | Who Wants the Caliphate? Editor’s Note This publication was scheduled for release before the news of the death of ISIS leader Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi. -

NATO and Earth Scientists: an Ongoing Collaboration to Assess Geohazards and Contribute to Societal Security in Central Asia and the Caucasus

Article 193 by Alessandro Tibaldi1*, Andrey M. Korzhenkov2, Federico Pasquarè Mariotto3, Derek Rust4, and Nino Tsereteli5 NATO and earth scientists: an ongoing collaboration to assess geohazards and contribute to societal security in Central Asia and the Caucasus 1 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Milano-Bicocca, P. della Scienza 4, 20126 Milan, Italy; *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] 2 Laboratory of modelling of seismic processes, Institute of Communication and Information Technologies, Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University, Kievskaya str. 44, Bishkek 720000, Kyrgyz Republic 3 Department of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, University of Insubria, Via Mazzini 5, 21100 Varese, Italy 4 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Portsmouth, Barnaby Building, Portsmouth PO1 2UP, UK 5 M. Nodia Institute of Geophysics, M. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, 1, Alexidze str. 0171 T, Georgia (Received: July 18, 2017; Revised accepted: February 26, 2018) https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2018/018011 Geological features and hazards have no geographical and political boundaries. The North Atlantic Treaty Introduction Organization (NATO) has been funding several interna- tional Earth Science research projects in Central Asia Several areas on Earth are subject to natural hazards that threaten and the Caucasus over the last ten years. The projects are human life, settlements and infrastructures. One of the natural haz- ards that may severely affect local areas and communities is an earth- aimed at improving the security of people and the safety quake, as seen, for instance, in the recent sequence of seismic events of infrastructures, and fostering peaceful scientific col- that struck the Caucasus: the 1988 earthquake in Spitak, Armenia laboration between scientists from NATO and non-NATO (Griffin et al., 1991), the 1991 and 2009 Racha (Georgia) earthquakes countries. -

Repositioning of the Global Epicentre of Non-Optimal Cholesterol

Article Repositioning of the global epicentre of non-optimal cholesterol https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2338-1 NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC)* Received: 18 October 2019 Accepted: 2 April 2020 High blood cholesterol is typically considered a feature of wealthy western 1,2 Published online: 3 June 2020 countries . However, dietary and behavioural determinants of blood cholesterol are changing rapidly throughout the world3 and countries are using lipid-lowering Open access medications at varying rates. These changes can have distinct effects on the levels of Check for updates high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol, which have different effects on human health4,5. However, the trends of HDL and non-HDL cholesterol levels over time have not been previously reported in a global analysis. Here we pooled 1,127 population-based studies that measured blood lipids in 102.6 million individuals aged 18 years and older to estimate trends from 1980 to 2018 in mean total, non-HDL and HDL cholesterol levels for 200 countries. Globally, there was little change in total or non-HDL cholesterol from 1980 to 2018. This was a net effect of increases in low- and middle-income countries, especially in east and southeast Asia, and decreases in high-income western countries, especially those in northwestern Europe, and in central and eastern Europe. As a result, countries with the highest level of non-HDL cholesterol—which is a marker of cardiovascular risk— changed from those in western Europe such as Belgium, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Malta in 1980 to those in Asia and the Pacific, such as Tokelau, Malaysia, The Philippines and Thailand. -

Count Me In; Resource Manual on Disabilities. INSTITUTION PACER Center, Inc., Minneapolis, KN

ED 341 218 EC 300 893 AUTHOR Milota, Cathy; And Others TITLE Count Me In; Resource Manual on Disabilities. INSTITUTION PACER Center, Inc., Minneapolis, KN. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 121p. AVAILABLE FROMPACER Center, 4826 Chicago Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55417-1055 ($15.00). PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classrcom Use (055) EDRS PRICE ,MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Assisive Devices (for Disabled); Autism; *Disabilities; *Educational Legislation; Educational Resources; Elementary Secondary Education; EMotional Disturbances; *Federal Legislation; Hearing Impairments; *Intervention; Learning Disabilities; Mental Retardation; Multiple Disabilities; Physical Disabilities; Preschool Education; Simulation; Special Health Problems; Speech Handicaps; *Symptoms (Individual Disorders); Visual Impairments IDENTIFIERS Americans with Disabilities Act 1990; Education for All Handicapped Children Act; Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments 1986; Impairment Severity; Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; Rehabilitation Act 1973 (Section 504) ABSTRACT This resource guide presents general information about disabilities and summaries of relevant federal laws. A question-and-answer format is used to highlight key features of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142, reauthorized in 1990 as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act); Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973; Public Law 99-457; and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Then individual sections provide information on vision impairments, hearing impairments, speech impairments, physical disabilities, mental retardation, learning disabilities, multiple disabilities, emotional disorders, autism, and other health impairments. Information provided typically includes the nature of the impairment, severity factors, associated problems, aids and appliances, therapeutic or remediation approaches, simulation activities, and resources (books for both children and adults as well as organizations). -

The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival

n the basis on solid fieldwork in northern Nigeria including participant observation, 18 Göttingen Series in Ointerviews with Izala, Sufis, and religion experts, and collection of unpublished Social and Cultural Anthropology material related to Izala, three aspects of the development of Izala past and present are analysed: its split, its relationship to Sufis, and its perception of sharīʿa re-implementation. “Field Theory” of Pierre Bourdieu, “Religious Market Theory” of Rodney Start, and “Modes Ramzi Ben Amara of Religiosity Theory” of Harvey Whitehouse are theoretical tools of understanding the religious landscape of northern Nigeria and the dynamics of Islamic movements and groups. The Izala Movement in Nigeria Genesis, Fragmentation and Revival Since October 2015 Ramzi Ben Amara is assistant professor (maître-assistant) at the Faculté des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Sousse, Tunisia. Since 2014 he was coordinator of the DAAD-projects “Tunisia in Transition”, “The Maghreb in Transition”, and “Inception of an MA in African Studies”. Furthermore, he is teaching Anthropology and African Studies at the Centre of Anthropology of the same institution. His research interests include in Nigeria The Izala Movement Islam in Africa, Sufism, Reform movements, Religious Activism, and Islamic law. Ramzi Ben Amara Ben Amara Ramzi ISBN: 978-3-86395-460-4 Göttingen University Press Göttingen University Press ISSN: 2199-5346 Ramzi Ben Amara The Izala Movement in Nigeria This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Published in 2020 by Göttingen University Press as volume 18 in “Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology” This series is a continuation of “Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie”. -

Political Repression in Sudan

Sudan Page 1 of 243 BEHIND THE RED LINE Political Repression in Sudan Human Rights Watch/Africa Human Rights Watch Copyright © May 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-75962 ISBN 1-56432-164-9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was researched and written by Human Rights Watch Counsel Jemera Rone. Human Rights Watch Leonard H. Sandler Fellow Brian Owsley also conducted research with Ms. Rone during a mission to Khartoum, Sudan, from May 1-June 13, 1995, at the invitation of the Sudanese government. Interviews in Khartoum with nongovernment people and agencies were conducted in private, as agreed with the government before the mission began. Private individuals and groups requested anonymity because of fear of government reprisals. Interviews in Juba, the largest town in the south, were not private and were controlled by Sudan Security, which terminated the visit prematurely. Other interviews were conducted in the United States, Cairo, London and elsewhere after the end of the mission. Ms. Rone conducted further research in Kenya and southern Sudan from March 5-20, 1995. The report was edited by Deputy Program Director Michael McClintock and Human Rights Watch/Africa Executive Director Peter Takirambudde. Acting Counsel Dinah PoKempner reviewed sections of the manuscript and Associate Kerry McArthur provided production assistance. This report could not have been written without the assistance of many Sudanese whose names cannot be disclosed. CONTENTS -

Genocide and Deportation of Azerbaijanis

GENOCIDE AND DEPORTATION OF AZERBAIJANIS C O N T E N T S General information........................................................................................................................... 3 Resettlement of Armenians to Azerbaijani lands and its grave consequences ................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Iran ........................................................................................ 5 Resettlement of Armenians from Turkey ................................................................................... 8 Massacre and deportation of Azerbaijanis at the beginning of the 20th century .......................... 10 The massacres of 1905-1906. ..................................................................................................... 10 General information ................................................................................................................... 10 Genocide of Moslem Turks through 1905-1906 in Karabagh ...................................................... 13 Genocide of 1918-1920 ............................................................................................................... 15 Genocide over Azerbaijani nation in March of 1918 ................................................................... 15 Massacres in Baku. March 1918................................................................................................. 20 Massacres in Erivan Province (1918-1920) ............................................................................... -

2019 Annual Report Our Conservation Supporters

2019 ANNUAL REPORT TO THE OUR CONSERVATION SUPPORTERS Partnerships with a Purpose Every piece of wetland or associated upland habitat A special thanks to our conserved by Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC) is the result of partnerships. These partnerships are the government partners: foundation of DUC’s conservation leadership and the The governments listed below The State of Idaho reason why we so clearly envision a future for wetland have provided instrumental The State of Indiana conservation in North America. support in Canada over the The State of Kansas Today, this continent-wide network of conservation past year. staff, volunteers and supporters ensures that Ducks The Government of Canada The State of Kentucky Unlimited Canada, Ducks Unlimited, Inc., and The Government of Alberta The State of Louisiana Ducks Unlimited Mexico play leadership roles in The State of Maine international programs like the North American The Government of British Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP). Established Columbia The State of Maryland in 1986, NAWMP is a partnership of federal, provincial, The Government of Manitoba The State of Massachusetts state and municipal governments, nongovernmental The Government of The State of Michigan organizations, private companies and many individuals, New Brunswick all working towards achieving better wetland habitat The State of Minnesota for the benefit of waterfowl, other wetland associated The Government of The State of Mississippi wildlife and people. DUC is proud to be closely Newfoundland and Labrador The State of Missouri associated with NAWMP, one of the most successful The Government of the conservation initiatives in the world. Northwest Territories The State of Nebraska The State of Nevada The North American Wetlands Conservation Act The Government of (NAWCA), enacted by the U.S. -

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I a L L I B R a R Y

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CHRONOLOGY Chronology of events that led Azerbaijan to independence and remarkable days after gaining the independence An extraordinary session of the Council of People's Deputies February 20,1988 of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Republic (NKAR) was held in Hankendi. The session appealed to the Presidium of Supreme Soviet of Azerbaijan and Armenia with the request that they treat with understanding the decision to sever the NKAR from Azerbaijan SSR and transfer it to Armenian SSR. It was also applied to the Supreme Soviet of the USSR for the positive solution of this issue. February 22,1988 Two young Azerbaijanis were killed by Armenians in Askeran February 28,1988 Bloody outrages were perpetrated by Armenian instigators in Sumgait March 24, 1988 By the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Azerbaijan SSR an official prohibition was imposed on activity of separatist organization "Krung" to be accused of breeding strife among the peoples. Abdurrahman Vezirov was elected the first secretary of the Central May 21,1988 Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party. The session of the Council of People's Deputies of the NKAR July 12, 1988 adopted an illegal decree on annexation of autonomous region to the Armenian SSR. July 18, 1988 The issue “About decisions of the Supreme Councils of the Armenian SSR and the Azerbaijan SSR regarding Nagorno- Karabakh” was discussed at the enlarged meeting of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council.