60441229.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festival Fever Sequel Season Fashion Heats Up

arts and entertainment weekly entertainment and arts THE SUMMER SEASON IS FOR MOVIES, MUSIC, FASHION AND LIFE ON THE BEACH sequelmovie multiples season mean more hits festival fever the endless summer and even more music fashionthe hemlines heats rise with up the temps daily.titan 2 BUZZ 05.14.07 TELEVISION VISIONS pg.3 One cancelled in record time and another with a bleak future, Buzz reviewrs take a look at TV show’s future and short lived past. ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR SUMMER MOVIE PREVIEW pg.4 Jickie Torres With sequels in the wings, this summer’s movie line-up is a EXECUTIVE EDITOR force to be reckoned with. Adam Levy DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING Emily Alford SUIT SEASON pg.6 Bathing suit season is upon us. Review runway trends and ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ADVERTISING how you can rock the baordwalk on summer break. Beth Stirnaman PRODUCTION Jickie Torres FESTIVAL FEVER pg.6 ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Summer music festivals are popping up like the summer Sarah Oak, Ailin Buigis temps. Take a look at what’s on the horizon during the The Daily Titan 714.278.3373 summer months. The Buzz Editorial 714.278.5426 [email protected] Editorial Fax 714.278.4473 The Buzz Advertising 714.278.3373 [email protected] Advertising Fax 714.278.2702 The Buzz , a student publication, is a supplemental insert for the Cal State Fullerton Daily Titan. It is printed every Thursday. The Daily Titan operates independently of Associated Students, College of Communications, CSUF administration and the WHAT’S THE BUZZ p.7 CSU system. The Daily Titan has functioned as a public forum since inception. -

ARTICLE American Movie Audiences of the 1930S1

ARTICLE American Movie Audiences of the 1930s1 Richard Butsch Rider University Abstract The Depression and movies with sound changed movie audiences of the 1930s from those of the 1920s and earlier. Sound silenced audiences, discouraging the sociabili- ty that had marked working-class audiences before. The Depression led movie com- panies to change marketing strategies and construction plans. They stopped selling luxury and building movie palaces. Instead, they expanded their operation of neigh- borhood theaters, displacing independents that had been more worker friendly, and instituted centrally controlled show bills and policies. Audiences also appear to have become more heterogeneous. All this, too, discouraged the voluble behavior of working-class people. Ironically, in this era of labor activism, workers and their fam- ilies seem to have become quieter in movie theaters, satisfied with the convenience of chain-operated movie houses. The 1930s were an exciting decade for labor activism in the United States and a high point for the growth of unions. Workers in steel, automobile, and other heavy industries organized industrial unions. The Committee on Industrial Or- ganization (later Congress of Industrial Organizations or CIO) was formed with a membership of more than a million workers. Factory workers initiated new tactics in struggles with employers, such as sit-down strikes. In politics, they ad- vanced legislation and programs in the New Deal to help employed and unem- ployed workers. Ironically, at the same time that workers’ collective action and class con- sciousness were at a high point, movie audiences became quiet. They did not act collectively to control their experience in the theater. -

Sloane Drayson Knigge Comic Inventory (Without

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Number Donor Box # 1,000,000 DC One Million 80-Page Giant DC NA NA 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 A Moment of Silence Marvel Bill Jemas Mark Bagley 2002 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alex Ross Millennium Edition Wizard Various Various 1999 NA Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Open Space Marvel Comics Lawrence Watt-Evans Alex Ross 1999 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alf Marvel Comics Michael Gallagher Dave Manak 1990 33 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 1 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 2 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 3 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 1999 4 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 5 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Alleycat Image Bob Napton and Matt Hawkins NA 2000 6 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Aphrodite IX Top Cow Productions David Wohl and Dave Finch Dave Finch 2000 0 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 600 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 601 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Veronica Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 602 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 603 Sloane Drayson-Knigge 1 Archie Marries Betty Archie Comics Publications Michael Uslan Stan Goldberg 2009 -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

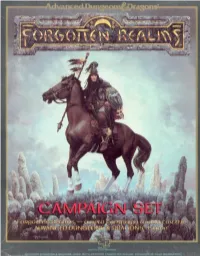

The Forgotten Realms Are a World of the Realms, Matched by a Sheet of Very Similar to the Earth of the 13Th and Ice, Equally Relentless, to Its East

These things also I have observed: that knowledge of our world is to be nurtured like a precious flower, for it is the most precious thing we have. Wherefore guard the word written and heed words unwrittenand set them down ere they fade . Learn then, well, the arts of reading, writing, and listening true, and they will lead you to the greatest art of all: understanding. Alaundo of Candlekeep Cyclopedia of the Realms Table of Contents Introductions ..................................................................4 About this Product ..............................................................5 Time in the Realms ..............................................................6 Names in the Realms .............................................................7 Languages of the Realms .........................................................8 Currency in the Realms ..........................................................9 Religion in the Realms ...........................................................10 Cyclopedia Entries ..............................................................19 Anauroch Map ..................................................................23 Arabel Map ....................................................................24 Cormyr Map ...................................................................33 Cormyr Royal Lineage ...........................................................34 DalelandsMap ..................................................................36 Immersea Map ..................................................................53 -

Amends Script

Amends (October 31, 1998) Written by: Joss Whedon Teaser EXT. DUBLIN STREET - NIGHT (1838) A Dickensian vista of Christmas. Snow covers the street (though it is not falling now), people and carriages milling about in it. A group of five or so CAROLLERS stand by one corner, singing a traditional Christmas air. A young man (DANIEL) in a dark suit makes his way through the people, quickly and nervously. He looks about him constantly. He passes an alley and he is suddenly GRABBED and pulled inside. He lands in a heap in the corner, the figure that grabbed him standing over him. ANGEL Why, Daniel, wherever are you going? Angel is dressed similarly -- though a bit more elegantly -- to Daniel. He is smiling graciously, and in full vampface. Daniel cowers, scrambling backwards. DANIEL You -- you're not human... ANGEL Not of late, no. DANIEL What do you want? ANGEL Well, it happens that I'm hungry, Daniel, and seeing as you're somewhat in my debt... DANIEL Please... I can't... ANGEL A man playing at cards should have a natural intelligence or a great deal of money and you're sadly lacking in both. So I'll take my winnings my own way. He grabs him, hoists him up. Daniel cannot wrest Angel's grasp from his throat. He Buffy Angel Show babbles quietly: DANIEL The lord is my shepherd, I shall not want... he maketh me to lie down in green pastures... he... ANGEL Daniel. Be of good cheer. (smiling) It's Christmas! He bites. INT. MANSION - ANGEL'S BEDROOM - NIGHT Angel awakens in a start, sweating. -

Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters the Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M

Sept/Oct 1998 £2.25 David Wingrove • John Meaney The Critical Tetsuo and Tetsuo II • Gattaca • John Wyndham Journal of George Orwell • Best of British Poll • Dr Who the BSFA Editorial Team Production and General Editing Tony Cullen - 16 Weaver's Way, Camden, London NW1 OXE Vector » Email: [email protected] Features, Editorial and Letters The Critical Journal of the BSFA Andrew M. Butler - 33 Brook View Drive, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5JN Email: [email protected] Contents Gary Dalkin - 5 Lydford Road, Bournemouth, 3 Editorial - The View from Hangar 23 Dorset, BH11 8SN by Andrew Butler Book Reviews 4 TO Paul Kincaid 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Letters to Vector Kent CT19 5AZ 5 Red Shift Email: [email protected] Corrections and Clarifications Printed by: 5 Afterthoughts: Reflections on having finished PDC Copyprint, 11 Jeffries Passage, Guildford, Chung Kuo Surrey GU1 4AP .by David Wingrove |The British Science Fiction Association Ltd. 6 Emergent Property An Interview with John Meaney by Maureen Kincaid Limited by guarantee. Company No. 921500. Registered Speller Address: 60 Bournemouth Road, Folkestone, Kent. CT19 5AZ 9 The Cohenstewart Discontinuity: Science in the | BSFA Membership Third Millennium by lohn Meaney UK Residents: £19 or £12 (unwaged) per year. 11 Man-Sized Monsters Please enquire for overseas rates by Colin Odell and Mitch Le Blanc 13 Gattaca: A scientific (queer) romance Renewals and New Members - Paul Billinger , 1 Long Row Close , Everdon, Daventry, Northants NN11 3BE by Andrew M Butler 15 -

Narcocorridos As a Symptomatic Lens for Modern Mexico

UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Vol. 1, No. 2 “Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro “The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic Fetishism and Fan Engagement with and Anthropological Lens to the War Horror Scores” on Drugs in Mexico” Spencer Slayton Samantha Cabral “Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s “This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Extremity in Thomas Adès’s The Acceptance in Shrek the Musical” Exterminating Angel” Clarina Dimayuga Lori McMahan “Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema” Liv Slaby Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief J.W. Clark Managing Editor Liv Slaby Review Editor Gabriel Deibel Technical Editors Torrey Bubien Alana Chester Matthew Gilbert Karen Thantrakul Graphic Designer Alexa Baruch Faculty Advisor Dr. Elisabeth Le Guin 1 UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1, Number 2 Spring 2020 Contents Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement 2 with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s Extremity in Thomas Adès’s 10 The Exterminating Angel Lori McMahan The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic and Anthropological Lens to 18 the War on Drugs in Mexico Samantha Cabral This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Acceptance in Shrek the 28 Musical Clarina Dimayuga Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema 38 Liv Slaby Contributors 50 Closing notes 51 2 Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton he horror genre is in the midst of a renaissance. The slasher craze of the late 70s and early 80s, revitalized in the mid-90s, is once again a popular genre for Treinterpretation by today’s filmmakers and film composers. -

A Photo Journal of Doctor Who Filming

www.dwasonline.co.uk for membership EDITORIAL details!) Editor John Davies who shares his by Grant Bull love of the brilliant Red Dwarf. Welcome back one and all, Our cover this time is by the always amazing Paul Watts. As is the norm with Paul I gave Firstly I would like to thank all those that him a brief for the commission and he blew downloaded #1 and said lovely things about my mind with the end product. Nothing I saw it. The stats look good and a wide audience in my head looked this good. Incredible art. was reached but I’m hoping this issue will Check out more of Paul’s masterpieces at surpass those numbers though, so keep www.paulwatts-illustration.co.uk downloading please... and not just you Mum! My thanks again to all those involved in this issue, it would have been a blank document This issue we have a nice selection of without you, so thanks for your willingness reviews, fiction and art, along with a couple to be a part of this project. Submissions for of interviews with people behind Who further issues, feedback or virtual take-away related projects. We also introduce a new menus can be sent to [email protected] feature called ‘Other than Who’ the idea being someone is invited to discuss one of Until next time, their other favourite shows after Doctor Who. The first piece is by the ever-reliable G Celestial Toyroom (little plug there, check out Cosmic Masque Issue 2 April 2016 Published by the Doctor Who Appreciation Society Front cover by Paul Watts Layout by Nicholas Hollands All content is © relevant contributor/DWAS Doctor Who is (C) BBC No copyright infringement is intended CONTACT US DWAS, Unit 117, 33 Queen Street, Horsham, RH13 5AA FIND US ONLINE www.dwasonline.co.uk facebook.com/dwasonline twitter.com/dwas63 youtube.com/dwasonline - 2 - Series Review years ago this March but and, in what is the first credit to this book, the text manages to The Black fit this still recent living memory of Who-lore in with past and future adventures without archive making the reader feel that passing decade (plus one) too keenly. -

Buffy the Vampire Slayer Fights Back Generate Attack, Recruit Points, and Against the Players! the Big Bad, Like Special Abilities

® ™ Overview How to Win Welcome to Legendary ®: Buffy the Players must work together to attack Vampire Slayer! Big Bads like the evil Big Bad successfully four The Master, Angelus, and Glorificus times. If they do this, then the Big command a mob of Demonic Villains, Bad is beaten once and for all, and planning dark Schemes to wreak all the players win the game for the havoc on Sunnydale, home of the forces of good! In addition, defeating Hellmouth. Only you can stop them Villains and rescuing Bystanders by leading Buffy and the rest of the earns each player Victory Points. Scooby gang. After the Big Bad is defeated, the player with the most Victory Points In this game for 1-5 players, each is the best slayer of all and the player starts with their own deck individual winner. of basic cards. At the start of your turn, you play the top card of the Villain Deck for Villains to invade How the Evil the Sunnydale, capture Bystanders, Big Bad Wins and create special events. Then, you Unlike other games, Legendary ®: play Hero cards from your hand to Buffy the Vampire Slayer fights back generate Attack, Recruit Points, and against the players! The Big Bad, like special abilities. You use your Attack The Master or Angelus, isn’t played to defeat Villains. You use Recruit by a player. Instead, the game itself Points to recruit better Heroes for plays the part of the Big Bad. your deck. Throughout the game the Big Whenever your deck runs out of Bad works to accomplish an evil cards, you shuffle your discard pile Scheme. -

Subscribe Today! (817) 460-7220

SPOTLIGHT: 2015 Park Preview Pages 6-9 TM & ©2015 Amusement Today, Inc. May 2015 | Vol. 19 • Issue 2 www.amusementtoday.com Europa-Park celebrates four decades Carowinds unveils of success with new attractions AT: Tim Baldwin B&M Fury 325 [email protected] RUST, Germany — Call it a birthday, call it an anniversa- ry, but Europa-Park has made it a celebration. On March 28, Roland Mack, the Mack family, the mayor (burgermeister) of Rust and special guests opened the park with a ribbon-cutting amid a flurry of showering confetti, balloons, and songs of celebration. The ceremony included a welcome from co- founder Roland Mack that reflected not only on how the park had changed over four decades, but the European community as well. Relation- ships across borders back in 1975 were a far cry from what they are today. It is that in- vigorated sense of European connectivity that has helped Germany’s largest theme park find astounding success. The mayor presented the park with a special gift for its 40th: a framed site permit drawing from when the park opened in The Dream Dome showcases the beauty of Europe in a relax- 1975. Appearing in flash mob ing high-definition film experience for Europa-Park guests. style, costumed entertainers, COURTESY EUROPA-PARK as well as staff from the vari- ous departments within the ment. “light” year blossomed into park and the resort got the New attractions dozens of construction proj- crowd clapping and energized For what was supposed ects. Jakob Wahl, director of for the opening. The official to be a “light” year in terms communications, reports, “We ribbon cutting sent the crowds of investments, following the had days with more than 2,000 running forward.