James Jones, Author of from Here to Eternity and the Thin Red Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

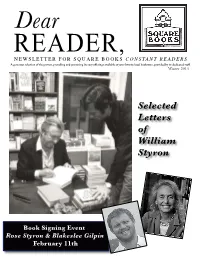

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2004 Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford John Louis Fuller Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Fuller, John Louis, "Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford" (2004). Honors Theses. 2005. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2005 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faulkner’s Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford Bv John L. Fuller A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2005 Advisor; Dr. Judson D. Wafson -7 ■ / ^—- Reader: Dr. Benjamin F. Fisher y. Reader: Dr. Andrew P. D^rffms Copyright © by John L. Fuller All Rights Reserved 1 For my parents Contents Abstract 5 I The Beginnings 9 (4Tell About the South 18 A Literary Awakening 25 II If You Build It, They Will Come 35 An Interview with Pochard Howorth 44Football, Faulkner, and Friends 57 An Interview with Barry Hannah Advancing Oxford’s Message 75 An Interview with Ann J. Abadie Oxford Tom 99 An Interview with Tom Franklin III Literary Grounds 117 Works cited 120 Abstract The genesis of this project was a commercial I saw on television advertising the University of Mississippi. “Is it the words that capture a place, or the place that captures the words?” noted actor and Mississippi native Morgan Freeman asked. -

John Coward on in Search of Willie Morris: the Mercurial Life Of

Larry L King. In Search of Willie Morris: The Mercurial Life of a Legendary Writer and Editor. New York: PublicAffairs, 2006. 353 pp. $26.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-58648-384-5. Reviewed by John M. Coward Published on Jhistory (July, 2007) When Willie Morris ascended to the editor's For a glorious cultural moment, Harper's and its desk at Harper's in 1967, he was perhaps the brilliant young editor were the talk of New York brightest star in American magazine journalism. publishing. Morris dined at Elaine's and partied At thirty-two, he was the youngest editor in the with the likes of Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bern‐ magazine's 117-year history--and perhaps its most stein, and Mickey Mantle. Larry L. King tells of audacious. A small-town Mississippi boy of prodi‐ one Manhattan party where Senator Ted Kennedy gious literary talent, Morris was also a painfully mistook the shirt-sleeved Harper's editor for a complex man ill-suited to the editor's chair. In the bartender and asked him for a scotch and soda. first place, he was an individualist in a business Morris complied--prompting a Kennedy apology that required teamwork. He hated meetings. He once the laughing stopped. avoided office correspondence. Morris was also Larry L. King, Morris's long-time friend (and an inveterate raconteur, far too fond of the bottle occasional antagonist), tells these stories and to become a stalwart of the magazine industry. more in this clear-eyed biography of Willie Mor‐ But Morris loved Harper's and he was deter‐ ris, a magazine editor who in many ways embod‐ mined to re-energize the venerable publication. -

Throughout His Writing Career, Nelson Algren Was Fascinated by Criminality

RAGGED FIGURES: THE LUMPENPROLETARIAT IN NELSON ALGREN AND RALPH ELLISON by Nathaniel F. Mills A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alan M. Wald, Chair Professor Marjorie Levinson Professor Patricia Smith Yaeger Associate Professor Megan L. Sweeney For graduate students on the left ii Acknowledgements Indebtedness is the overriding condition of scholarly production and my case is no exception. I‘d like to thank first John Callahan, Donn Zaretsky, and The Ralph and Fanny Ellison Charitable Trust for permission to quote from Ralph Ellison‘s archival material, and Donadio and Olson, Inc. for permission to quote from Nelson Algren‘s archive. Alan Wald‘s enthusiasm for the study of the American left made this project possible, and I have been guided at all turns by his knowledge of this area and his unlimited support for scholars trying, in their writing and in their professional lives, to negotiate scholarship with political commitment. Since my first semester in the Ph.D. program at Michigan, Marjorie Levinson has shaped my thinking about critical theory, Marxism, literature, and the basic protocols of literary criticism while providing me with the conceptual resources to develop my own academic identity. To Patricia Yaeger I owe above all the lesson that one can (and should) be conceptually rigorous without being opaque, and that the construction of one‘s sentences can complement the content of those sentences in productive ways. I see her own characteristic synthesis of stylistic and conceptual fluidity as a benchmark of criticism and theory and as inspiring example of conceptual creativity. -

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

THE JAMES JONES LITERARY SOCIETY NEWSLETTER on the Trail of Jones and Prewitt in Hawaii

THE JAMES JONES LITERARY SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Vol. 10, No. 3, Spring, 2001 Editor Thomas J. Wood Editorial Advisory Board Dwight Connelly Kevin Heisler Richard King Michael Mullen The James Jones Society Newsletter is published quarterly to keep members and interested parties apprised of activities, projects and upcoming events of the Society; to promote public interest and academic research in the works of James Jones; and to celebrate his memory and legacy. Submissions of essays, features, anecdotes, photographs, etc., that pertain to author James Jones may be sent to the editor for publication consideration. Every attempt will be made to return material, if requested upon submission. Material may be edited for length, clarity and accuracy. Send submissions to: Thomas J. Wood Archives/Special Collections, LIB 144 University of Illinois at Springfield P.O. Box 19243 Springfield, IL, 62794-9423 [email protected]. Writers guidelines available upon request and online. The James Jones Literary Society http://jamesjoneslitsociety.vinu.edu/ Online information about the James Jones First Novel Fellowship http://wilkes.edu/~english/jones.html On the Trail of Jones and Prewitt in Hawaii: JJLS Members Becker and Thobaben Recreate their Kolekole Hike [Carl Becker and Robert Thobaben are veterans of the Pacific Theater in WWII and now teach at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. They first recreated Robert E. Lee Prewitt's fictional hike to Oahu's Kolekole Pass in 1991. Earlier this year they again made the hike. Here is Carl Becker's account of their adventure. - ed.] As many members of the Society know, Bob Thobaben and I went to Schofield Barracks in Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands in 1991 and there recreated Robert E. -

Oregon Trails--What's on Your Nightstand? Thomas W

Against the Grain Volume 28 | Issue 1 Article 24 2016 Oregon Trails--What's On Your Nightstand? Thomas W. Leonhardt [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/atg Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Leonhardt, Thomas W. (2018) "Oregon Trails--What's On Your Nightstand?," Against the Grain: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.7282 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Oregon Trails — What’s On Your Nightstand? Column Editor: Thomas W. Leonhardt (Retired, Eugene, OR 97404) <[email protected]> y favorite section of The New York of essays by a Holocaust survivor and Der You’re hosting a liter- Times Book Review is called “By Geteilte Himmel (The Divided Heaven), by ary dinner party. Which Mthe Book.” The column editor asks Christa Wolf. Wolf is the most popular and three writers are invited? general book-related questions of a writer or important writer to come from the Deutsche James Jones, William celebrity and then throws in a few more ques- Demokratische Republik (East Germany). Styron, and Willie Morris. tions that are based on the person’s genre, or a For quieter, more thoughtful moods I can They might drink more writer, or area of expertise. open A History of Philosophy by Frederick than they would eat but it would be an unfor- Being neither famous nor accomplished, I Copleston, S.J. -

The 2007 Oxford Conference for the Book

Southern Register Winter 2k7 2/19/07 3:28 PM Page 1 the THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF SOUTHERN CULTURE •WINTER 2007 THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI 2007 Oxford Conference for the Book his year’s Oxford Conference for the Book will be a special one. The conference honors each year a Tprominent Southern writer, and Larry Brown will be the focus of attention when the 14th annual conference meets on March 22–24, 2007. Brown was one of the South’s, and nation’s, most acclaimed younger writers, when he died November 24, 2004. The conference will provide the first literary occasion to gather critics, scholars, musicians, teachers, friends, and family to consider and celebrate Brown’s achievements. Brown was an especially well known figure around Oxford. Having grown up in Lafayette County, he studied writing at the University of Mississippi, taught here briefly, and had been a frequent participant in Center work. Brown was a legendary figure—the Oxford firefighter who served the community from 1973 to 1990, when he retired to work full time on his writing. He studied with Mississippi writer Ellen Douglas, and his wide reading and relentless work on his writing contributed to his prolific success. He published his first book, Facing the Music: Short Stories, in 1988. He wrote five novels, a second short-story collection, and two books of nonfiction. His last novel, A Miracle of Catfish, will be published by Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill on March 20, just before the conference begins. Illustrating 2007 Oxford Conference for the Book materials is a Brown received the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters Larry Brown portrait made by Tom Rankin in 1996. -

Praise for James Jones's Wwii

PRAISE FOR JAMES JONES’S WWII “Th e most stirring and lucid account of World War II that I have ever read.” Joseph Heller “[Jones] overcomes the vastness of the event by emphasizing his personal experience of it, thus giving the reader a foothold in the text that is far more satisfying than gliding across a glossy overview. He overcomes his limited viewpoint of the war by symbolizing it in the experience of the common infantryman and locating in that experience a unique signifi cance.” Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, New York Times, 1975 “Anytime he writes of war you can smell the gunsmoke. A book like this was needed to remind us what it was like. A remarkable achievement.” James Michener “Jones is a man of experience and memories. [He] has writ- ten WWII with passion, projected in accounts of actions he never saw no less than of actions in which he participated . anyone can salute WWII as providing vivid vicarious experiences, a mind- bending extension into new territory of whatever one knew before, not only about war but about human nature.” Alfred C. Ames, Chicago Tribune, 1975 “An expert, eloquent personal remembrance of batt les past, what it felt like to live each day as possibly one’s last, what it felt like to go into batt le, and fi nally what it felt like to get hit . writt en by one of the best combat novelists of our time.” San Francisco Examiner & Chronicle “Spectacular and revealing.” National Observer “Amazing . with his inimitable bent for realism, his perception and his combat infantry experiences in the South Pacifi c, he has somehow managed to write about the whole war, in all its far-fl ung theatres, and with its entire cast of combatants . -

Evolution of a Soldier in James Jones's from Here to Eternity

===================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:3 March 2018 Dr. T. Deivasigamani, Editor: Vol. II Black Writings: A Subaltern Perspective Annamalai University, Tamilnadu, India ===================================================================== Evolution of a Soldier in James Jones’s From Here to Eternity M. Kumaran and Dr. C. Santhosh Kumar ==================================================================== Courtesy: https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/88405/from-here-to-eternity-by- james-jones/9780812984316/ Abstract James Jones, one of the famous novelists of his generation, was well known for his War Fiction. Jones portrays the courage, violence and passion of men who lived army life. He highlights the male narrative appearance and the discourses of masculinity in 1950’s. In From Here to Eternity, he discusses how a civilian persuades into army life. He describes the evolution of soldier in three stages; civilian to soldier, soldier to combat soldier, combat soldier to civilian. The characters of his novel find difficult to express their feelings and emotions aloud in army =================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:3 March 2018 Dr. T. Deivasigamani, Editor: Vol. II Black Writings: A Subaltern Perspective M. Kumaran and Dr. C. Santhosh Kumar Evolution of a Soldier in James Jones’s From Here to Eternity 109 life. Inside each of them, they strive for more knowledge and more spiritual connection to the world. War don’t ennoble men, it turns’em into dogs. It poisons the soul. - James Jones Evolution of a Soldier James Jones discusses the concept of evolution of a soldier representing that evolution has been one of the chief aims of his fictional trilogy.