The Asianization of the Future Metropolis in Post-Blade Runner Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jational Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

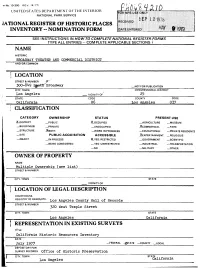

•m No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE JATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS >_____ NAME HISTORIC BROADWAY THEATER AND COMMERCIAL DISTRICT________________________ AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER <f' 300-8^9 ^tttff Broadway —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Los Angeles VICINITY OF 25 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE California 06 Los Angeles 037 | CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^.OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED .^COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE .XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ^ENTERTAINMENT _ REUGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2L.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: NAME Multiple Ownership (see list) STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE VICINITY OF | LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDSETC. Los Angeie s County Hall of Records STREET & NUMBER 320 West Temple Street CITY. TOWN STATE Los Angeles California ! REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTLE California Historic Resources Inventory DATE July 1977 —FEDERAL ^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS office of Historic Preservation CITY, TOWN STATE . ,. Los Angeles California DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE X.GOOD 0 —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Broadway Theater and Commercial District is a six-block complex of predominately commercial and entertainment structures done in a variety of architectural styles. The district extends along both sides of Broadway from Third to Ninth Streets and exhibits a number of structures in varying condition and degree of alteration. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

University of California, San Diego

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Comparative Literature by Xiangyang Liu Committee in charge: Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair Professor Larissa Heinrich Professor Wai-lim Yip 2010 The Thesis of Xiangyang Liu is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2010 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents…………….…………………………………………………...… iv Abstract………………………………………………………………..…................ v Introduction…………………………………………………………… …………... 1 Chapter One A Modern City in the Perspective of Two Generations……………………………... 3 Chapter Two Urban Culture: Transmission and circling………………………………………….. 27 Chapter Three Negotiation with Shanghai’s Present and Past…………………………………….... 51 Conclusion………………………...………………………………………………… 86 Bibliography..……………………..…………………………………………… …….. 90 iv ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Shanghai in Contemporary Chinese Film by Xiangyang Liu Master of Arts in Comparative Literature University of California, San Diego, 2010 Professor Yingjin Zhang, Chair This thesis is intended to investigate a series of films produced since the 1990s. All of these films deal with -

Close-Up on the Robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926

Close-up on the robot of Metropolis, Fritz Lang, 1926 The robot of Metropolis The Cinémathèque's robot - Description This sculpture, exhibited in the museum of the Cinémathèque française, is a copy of the famous robot from Fritz Lang's film Metropolis, which has since disappeared. It was commissioned from Walter Schulze-Mittendorff, the sculptor of the original robot, in 1970. Presented in walking position on a wooden pedestal, the robot measures 181 x 58 x 50 cm. The artist used a mannequin as the basic support 1, sculpting the shape by sawing and reworking certain parts with wood putty. He next covered it with 'plates of a relatively flexible material (certainly cardboard) attached by nails or glue. Then, small wooden cubes, balls and strips were applied, as well as metal elements: a plate cut out for the ribcage and small springs.’2 To finish, he covered the whole with silver paint. - The automaton: costume or sculpture? The robot in the film was not an automaton but actress Brigitte Helm, wearing a costume made up of rigid pieces that she put on like parts of a suit of armour. For the reproduction, Walter Schulze-Mittendorff preferred making a rigid sculpture that would be more resistant to the risks of damage. He worked solely from memory and with photos from the film as he had made no sketches or drawings of the robot during its creation in 1926. 3 Not having to take into account the morphology or space necessary for the actress's movements, the sculptor gave the new robot a more slender figure: the head, pelvis, hips and arms are thinner than those of the original. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

Gwendolyn Wright

USA modern architectures in history Gwendolyn Wright REAKTION BOOKS Contents 7 Introduction one '7 Modern Consolidation, 1865-1893 two 47 Progressive Architectures, ,894-'9,8 t h r e e 79 Electric Modernities, '9'9-'932 fau r "3 Architecture, the Public and the State, '933-'945 fi ve '5' The Triumph of Modernism, '946-'964 six '95 Challenging Orthodoxies, '965-'984 seven 235 Disjunctures and Alternatives, 1985 to the Present 276 Epilogue 279 References 298 Select Bibliography 305 Acknowledgements 3°7 Photo Acknowledgements 3'0 Index chapter one Modern Consolidation. 1865-1893 The aftermath of the Civil War has rightly been called a Second American Revolution.' The United States was suddenly a modern nation, intercon- nected by layers of infrastructure, driven by corporate business systems, flooded by the enticements of consumer culture. The industrial advances in the North that had allowed the Union to survive a long and violent COll- flict now transformed the country, although resistance to Reconstruction and racial equality would curtail growth in the South for almost a cen- tury. A cotton merchant and amateur statistician expressed astonishment when he compared 1886 with 1856. 'The great railway constructor, the manufacturer, and the merchant of to-day engage in affairs as an ordinary matter of business' that, he observed, 'would have been deemed impos- sible ... before the war'? Architecture helped represent and propel this radical transformation, especially in cities, where populations surged fourfold during the 30 years after the war. Business districts boasted the first skyscrapers. Public build- ings promoted a vast array of cultural pleasures) often frankly hedonistic, many of them oriented to the unprecedented numbers of foreign immi- grants. -

He Museum of Modern Art No

^2. he Museum of Modern Art No. 27 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 245-3200 Cable: Modernart Friday, March 7, I969 PRESS PREVIEW: Wednesday, March 5, I969 1 - k P.M. THE LOST FILM EXHIBIT AT THE MUSEUM PHOTOGRAPHIC GLORY OF VANISHED PAST The Lost Film, an exhibition of stills from early motion pictures that have disappeared or disintegrated, will be officially on view, starting March J, at The Museum of Modern Art, Scenes from 28 films from the twenties by such famous film directors as Erich von Stroheim, Josef von Sternberg, Howard Hawks, Tod Browning, and Frank Borzage are shown, including dramatic stills of Lon Chaney as a hypnotist. Norma Shearer, muffled by an unknown hand, Lewis Stone in the role of a libertine king, and Lionel Barrymore as the Greek manager of a side show. Many of the themes are melodramatic and moralistic with Fay V/ray, of King Kong fame shown as a member of the Salvation Army v;ho reprimands the gangster, Emil Jannings, in the picture "The Street of Sin," made in I928. By contrast "Polly of the Follies" (1922) has Constance Talmadge wearing a derby hat and smoking a cigar. Other black and white scenes come from "The World's Applause" (I923), "Merton of the Movies" (192^), "Confessions of a Queen," (I925), "The Devil's Circus" (I926), "The Show" (1927)^ "Drag Net" (I928), and "The Case of Lena Smith" (I929). They feature many famous actors, among them AdolpheMenjou, Monte Blue, Lillian Gish, George Bancroft, Bessie Love, John Gilbert, and Bebe Daniels. -

DICKENS on SCREEN, BFI Southbank's Unprecedented

PRESS RELEASE 12/08 DICKENS ON SCREEN AT BFI SOUTHBANK IN FEBRUARY AND MARCH 2012 DICKENS ON SCREEN, BFI Southbank’s unprecedented retrospective of film and TV adaptations, moves into February and March and continues to explore how the work of one of Britain’s best loved storytellers has been adapted and interpreted for the big and small screens – offering the largest retrospective of Dickens on film and television ever staged. February 7 marks the 200th anniversary of Charles Dickens’ birth and BFI Southbank will host a celebratory evening in partnership with Film London and The British Council featuring the world premiere of Chris Newby’s Dickens in London, the innovative and highly distinctive adaptation of five radio plays by Michael Eaton that incorporates animation, puppetry and contemporary footage, and a Neil Brand score. The day will also feature three newly commissioned short films inspired by the man himself. Further highlights in February include a special presentation of Christine Edzard’s epic film version of Little Dorrit (1988) that will reunite some of the cast and crew members including Derek Jacobi, a complete screening of the rarely seen 1960 BBC production of Barnaby Rudge, as well as day long screenings of the definitive productions of Hard Times (1977) and Martin Chuzzlewit (1994). In addition, there will be the unique opportunity to experience all eight hours of the RSC’s extraordinary 1982 production of Nicholas Nickleby, including a panel discussion with directors Trevor Nunn and John Caird, actor David Threlfall and its adaptor, David Edgar. Saving some of the best for last, the season concludes in March with a beautiful new restoration of the very rare Nordisk version of Our Mutual Friend (1921) and a two-part programme of vintage, American TV adaptations of Dickens - most of which have never been screened in this country before and feature legendary Hollywood stars. -

Swedish Male Sex Tourists in Prostitution Industries Abroad

“Welcome to Sin City” Swedish male sex tourists in prostitution industries abroad A report from Sweden's Fair Travel network “Welcome to Sin City” Swedish male sex tourists in prostitution industries abroad This report was written by Joakim Medin The aim of the Fair Travel network is that both on behalf of Schyst resande – Sweden's Fair tourism and business travel should contribute Travel network. The information is partly built to a sustainable development. That means, on interviews conducted in Thailand. among other things: Published: October 18th 2018 › Making sure that the workers in the tourism industry have decent working conditions. All photos by: Joakim Medin › Choosing climate-friendly and environmentally sound options. For enquiries about the report, contact: › Supporting locally owned businesses. Schyst resande /Fair Travel network › Acting against prostitution and trafficking. Helena Myrman, project manager, tel 070-257 03 04 › Refraining from activities that may [email protected] contribute to the exploitation of children. › Thinking about one's "alcohol footprint". Eight organizations are part of the Fair Travel network: Unionen, Childhood Foundation, Fair Action, The Hotel and Restaurant Workers' Union, the IOGT-NTO movement, Real- Stars, the Church of Sweden and Union to Union. “Welcome to Sin City” 4 Introduction Introduction Pattaya, Thailand, August 2018. 52-year-old “Karl” from Sweden is sucking intensely on the nipple he has just bought some playtime with. His eyes are half open, and with his left hand he is pinching and pulling the nipple of the other naked breast in front of him. Karl adores these nipples. He pointed them out from our sofa, calling them the biggest nipples he has ever seen in this strip club. -

Behind the Scenes

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 282 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to your submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. OUR READERS Dai Min Many thanks to the travellers who used the Massive thanks to Dai Lu, Li Jianjun and Cheng Yuan last edition and wrote to us with helpful hints, for all their help and support while in Shanghai, your useful advice and interesting anecdotes: Thomas assistance was invaluable. Gratitude also to Wang Chabrieres, Diana Cioffi, Matti Laitinen, Stine Schou Ying and Ju Weihong for helping out big time and a Lassen, Cristina Marsico, Rachel Roth, Tom Wagener huge thank you to my husband for everything.