Download (4MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

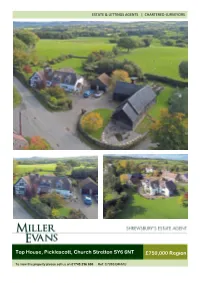

Vebraalto.Com

Top House, Picklescott, Church Stretton SY6 6NT £750,000 Region To view this property please call us on 01743 236 800 Ref: C7093/GM/MU A stunning and particularly attractive, Grade II Listed, 4 bedroom, detached property. Top House is a particularly attractive and stunning, Grade II Listed detached property with a wealth of character features throughout including exposed wall and ceiling timbers, stone fireplaces and original oak doors. The property provides particularly spacious and well planned accommodation throughout and briefly comprises : open fronted oak entrance porch, kitchen/breakfast room, dining room, front porch, garden room, cloakroom/wc, lounge, master bedroom with en suite, second bedroom with en suite, 2 further good sized bedrooms and a bathroom. A detached outbuilding/barn with full planning permission for residential conversion. Detached double garage. Stunning gardens with uninterrupted views and large private forecourt with ample parking. In total the property stands in approx. half an acre. The property occupies a picturesque setting in the small and unspoilt village of Picklescott which is nestled amongst the South Shropshire Hills in an area of outstanding natural beauty, approx. 10 miles south of Shrewsbury and 4 ½ miles north of Church Stretton. The property boasts stunning views and has the benefit of the popular Bottle and Glass Public House within walking distance. Further shops and amenities can be found in the nearby village of Dorrington which is approx. 3 miles away. INSIDE THE PROPERTY BEDROOM 2 17'9" x 13'6" (5.41m x 4.11m) OPEN FRONTED OAK PORCH 2 double built in wardrobes With solid wood entrance door leads into: Exposed ceiling beams Windows to the front and rear with lovely views over the garden and KITCHEN / BREAKFAST ROOM open countryside beyond. -

FOMA Members Honoured!

Issue Number 23: August 2011 £2.00 ; free to members FOMA Members Honoured! FOMA member Anne Wade was awarded the MBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours for services to the community in Rochester. In June, Anne received a bouquet of congratulations from Sue Haydock, FOMA Vice President and Medway Council Representative. More inside... Ray Maisey, Clock Tower printer became Deputy Mayor of Medway in May. Ray is pictured here If undelivered, please return to: with his wife, Buffy, Deputy Mayoress and FOMA Medway Archives office, member. Civic Centre, More inside... Strood, Rochester, Kent, ME2 4AU. The FOMA AGM FOMA members await the start of the AGM on 3 May 2011 at Frindsbury. Betty Cole, FOMA Membership Secretary, signed members in at the AGM and took payment for the FOMA annual subscription. Pictured with Betty is Bob Ratcliffe FOMA Committee member and President of the City of Rochester Society. April Lambourne’s Retirement The Clock Tower is now fully indexed! There is now a pdf on the FOMA website (www.foma-lsc.org/newsletter.html) which lists the contents of all the issues since Number 1 in April 2006. In addition, each of the past issues now includes a list of contents; these are highlighted with an asterisk (*). If you have missed any of the previous issues and some of the articles published, they are all available to read on the website . Read them again - A Stroll through Strood by Barbara Marchant (issue 4); In Search of Thomas Fletcher Waghorn (1800- 1850) by Dr Andrew Ashbee (issue 6); The Other Rochester and the Other Pocahontas by Ruth Rosenberg-Naparsteck (issue 6); Jottings in the Churchyard of Celebrating April All Saints Frindsbury by Tessa Towner (issue 8), The Skills of the Historian by Dr Lambourne’s retirement from Kate Bradley (issue 9); The Rosher Family: From Gravesend to Hollywood by MALSC at the Malta Inn, Amanda Thomas (issue 9); George Bond, Architect and Surveyor, 1853 to 1914 by Allington. -

PROGRAMME: July – October 2018

PROGRAMME: July – October 2018 MEETING POINTS Sunday Abbey Foregate car park (opposite The Abbey). 9.30 am. unless otherwise stated in programme. Tuesday Car park behind Harvester Beaten Track PH, Old Potts Way. 9.30 am. unless otherwise stated in programme. Thursday Car park behind Harvester Beaten Track PH, Old Potts Way. 9.30 am. unless otherwise stated in programme. Saturday As per programme. Sun 1 Jul Darren Hall (07837 021138) 7 miles Moderate+ Rectory Wood, up Town Brook Valley to Pole Bank, along the top of the Long Mynd to Pole Cottage, before returning via Ashes Hollow to Church Stretton. Tea afterwards at Berry's or Jemima's Tearooms. Walk leader will meet walkers at Easthope car park at 10:00. Meet 09:30 Abbey Foregate. Voluntary transport contribution £2 Tue 3 Jul John Law (01743 363895) 9 miles Moderate+ Cleobury Mortimer, Mamble & Bayton. Rural paths and tracks Meet 09:00 Harvester Car Park. Voluntary transport contribution £4 Wed 4 Jul Peter Knight (01743 246609) 4 miles Easy Meole Brace along the Reabrook and Shrewsbury School overlooking the Quarry. Start 19:00 Co-op Stores Radbrook (SJ476112). Thu 5 Jul Ken Ashbee (07972 012475) 6 miles Easy Powis Castle, once a medieval fortress. Track and field paths, lovely views. This is a NT property so bring your card if you are a member Meet 09:30 Harvester Car Park. Voluntary transport contribution £3 Sat 7 Jul Phil Barnes (07983 459531) 7 miles Moderate Leebotwood to Pulverbatch Bus Ramble via Picklescote taking in two motte and baileys and a, hard to find, church. -

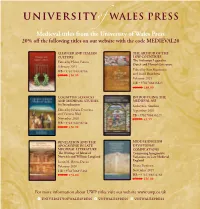

Medieval Titles from the University of Wales Press 20% Off the Following Titles on Our Website with the Code MEDIEVAL20

Medieval titles from the University of Wales Press 20% off the following titles on our website with the code MEDIEVAL20 CHAUCER AND ITALIAN THE ARTHUR OF THE CULTURE LOW COUNTRIES The Arthurian Legend in Edited by Helen Fulton Dutch and Flemish Literature February 2021 HB • 9781786836786 Edited by Bart Besamusca £70.00 £56.00 and Frank Brandsma February 2021 HB • 9781786836823 £80.00 £64.00 COGNITIVE SCIENCES INTRODUCING THE AND MEDIEVAL STUDIES MEDIEVAL ASS An Introduction Kathryn L. Smithies Edited by Juliana Dresvina September 2020 and Victoria Blud PB • 9781786836229 November 2020 £11.99 £9.59 HB • 9781786836748 £70.00 £56.00 REVELATION AND THE MIDDLE ENGLISH APOCALYPSE IN LATE DEVOTIONAL MEDIEVAL LITERATURE COMPILATIONS The Writings of Julian of Composing Imaginative Norwich and William Langland Variations in Late Medieval Justin M. Byron-Davies England February 2020 Diana Denissen HB • 9781786835161 November 2019 £70.00 £56.00 HB • 9781786834768 £70.00 £56.00 For more information about UWP titles visit our website www.uwp.co.uk B UNIVERSITYOFWALESPRESS A UNIWALESPRESS V UNIWALESPRESS 20% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL20 TRIOEDD YNYS PRYDEIN GEOFFREY OF MONMOUTH PRINCESSES OF WALES The Triads of the Island of Britain Karen Jankulak Deborah Fisher THE ECONOMY OF MEDIEVAL Edited by Rachel Bromwich PB • 9780708321515 £7.99 £4.00 PB • 9780708319369 £3.99 £2.00 WALES, 1067-1536 PB • 9781783163052 £24.99 £17.49 Matthew Frank Stevens GENDERING THE CRUSADES REVISITING THE MEDIEVAL PB • 9781786834843 £24.99 £19.99 THE WELSH AND Edited by Susan B. Edgington NORTH OF ENGLAND THE MEDIEVAL WORLD and Sarah Lambert Interdisciplinary Approaches INTRODUCING THE MEDIEVAL Travel, Migration and Exile PB • 9780708316986 £19.99 £10.00 Edited by Anita Auer, Denis Renevey, DRAGON Edited by Patricia Skinner Camille Marshall and Tino Oudesluijs Thomas Honegger HOLINESS AND MASCULINITY PB • 9781786831897 £29.99 £20.99 PB • 9781786833945 £35.00 £17.50 PB • 9781786834683 £11.99 £9.59 IN THE MIDDLE AGES 50% OFF WITH THE CODE MEDIEVAL50 Edited by P. -

Rural Settlement List 2014

National Non Domestic Rates RURAL SETTLEMENT LIST 2014 1 1. Background Legislation With effect from 1st April 1998, the Local Government Finance and Rating Act 1997 introduced a scheme of mandatory rate relief for certain kinds of hereditament situated in ‘rural settlements’. A ‘rural settlement’ is defined as a settlement that has a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable year in question. The Non-Domestic Rating (Rural Settlements) (England) (Amendment) Order 2009 (S.I. 2009/3176) prescribes the following hereditaments as being eligible with effect from 1st April 2010:- Sole food shop within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole general store within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole post office within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £8,500; Sole public house within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Sole petrol filling station within a rural settlement and has a RV of less than £12,500; Section 47 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988 provides that a billing authority may grant discretionary relief for hereditaments to which mandatory relief applies, and additionally to any hereditament within a rural settlement which is used for purposes which are of benefit to the local community. Sections 42A and 42B of Schedule 1 of the Local Government and Rating Act 1997 dictate that each Billing Authority must prepare and maintain a Rural Settlement List, which is to identify any settlements which:- a) Are wholly or partly within the authority’s area; b) Appear to have a population of not more than 3,000 on 31st December immediately before the chargeable financial year in question; and c) Are, in that financial year, wholly or partly, within an area designated for the purpose. -

The Origins of the English Pillow Lace Industry by G

The Origins of the English Pillow Lace Industry By G. F. R. SPENCELEY N her pioneering analysis, 'ladustries in the Countryside', Dr Thirsk suggested that the key to the development of the rural industries which existed in England I between the opening of the fifteenth and the middle of the seventeenth centuries lay in the socio-agrarian environment which produced the requisite labour sup- plies. ~ For no matter how close the prospective entrepreneur found himself to supplies of raw materials and sources of power, or to ports and centres of compelling market demand, he could not establish a rural industry unless he could fred a labour force. Indeed, the impetus for the development of rural industry probably came from within rural society itself as local populations searched for additional sources of income to supplement meagre returns from agriculture. Yet this was no haphazard evolution. Rural industries tended to develop in a distinct region of England, in "populous communities of small farmers pursuing a pastoral economy based either upon dairying or breeding, ''~ for it was here that the demands on agricultural labour were relatively slight, probably spasmodic, and farm work and excess rural population could easily turn to industrial employment as a result. There was far less likelihood of rural industries developing in arable areas, for arable agriculture exerted heavy demands on labour supplies. In Hertfordshire, for example, a small outpost of the cloth industry had died in the sixteenth century because of a switch to arable agriculture which, in the words of local magistrates, provided "better means" of employing the poor in "picking wheat a great part of the year and straining before the plough at seedtime and other necessary occasions of husbandry."4 Subsequent investigations led Dr Thirsk to suggest that if"an industry was to flourish on a scale sutticiently large to support a specialized market of repute.., it had to be able to draw on a considerable reserve of labour. -

Tna Prob 11/95/237

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/95/237 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the last will and testament, dated 14 February 1598 and proved 24 April 1600, of Oxford’s half-sister, Katherine de Vere, who died on 17 January 1600, aged about 60. She married Edward Windsor (1532?-1575), 3rd Baron Windsor, sometime between 1553 and 1558. For his will, see TNA PROB 11/57/332. The testatrix’ husband, Edward Windsor, 3rd Baron Windsor, was the nephew of Roger Corbet, a ward of the 13th Earl of Oxford, and uncle of Sir Richard Newport, the owner of a copy of Hall’s Chronicle containing annotations thought to have been made by Shakespeare. The volume was Loan 61 in the British Library until 2007, was subsequently on loan to Lancaster University Library until 2010, and is now in the hands of a trustee, Lady Hesketh. According to the Wikipedia entry for Sir Richard Newport, the annotated Hall’s Chronicle is now at Eton College, Windsor. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Newport_(died_1570) Newport's copy of his chronicle, containing annotations sometimes attributed to William Shakespeare, is now in the Library at Eton College, Windsor. For the annotated Hall’s Chronicle, see also the will of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), TNA PROB 11/53/456; Keen, Alan and Roger Lubbock, The Annotator, (London: Putnam, 1954); and the Annotator page on this website: http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/annotator.html For the will of Roger Corbet, see TNA PROB 11/27/408. -

Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race by Thomas William Rolleston This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Myths and Legends of the Celtic Race Author: Thomas William Rolleston Release Date: October 16, 2010 [Ebook 34081] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MYTHS AND LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE*** MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE Queen Maev T. W. ROLLESTON MYTHS & LEGENDS OF THE CELTIC RACE CONSTABLE - LONDON [8] British edition published by Constable and Company Limited, London First published 1911 by George G. Harrap & Co., London [9] PREFACE The Past may be forgotten, but it never dies. The elements which in the most remote times have entered into a nation's composition endure through all its history, and help to mould that history, and to stamp the character and genius of the people. The examination, therefore, of these elements, and the recognition, as far as possible, of the part they have actually contributed to the warp and weft of a nation's life, must be a matter of no small interest and importance to those who realise that the present is the child of the past, and the future of the present; who will not regard themselves, their kinsfolk, and their fellow-citizens as mere transitory phantoms, hurrying from darkness into darkness, but who know that, in them, a vast historic stream of national life is passing from its distant and mysterious origin towards a future which is largely conditioned by all the past wanderings of that human stream, but which is also, in no small degree, what they, by their courage, their patriotism, their knowledge, and their understanding, choose to make it. -

Town and Aberystwith Railway, Or

4441 by a junction with the Shrewsbury and Hereford, Hencott, Battlefield, Broughtpn, Saint Chad, Long- Shrewsbury and Wolverhampton, Shrewsbury, New- nor, -Fitz, Grinshill, Grinshill Haughmond, Saint town and Aberystwith Railway, or either of them, Mary, Albrighton, Astley .Berwick, Clive, Harlescott, or any other railway or railways at or near the said Leaton, Newton, Wollascott otherwise Woollascott, town and borough of Shrewsbury, in the county Middle Hadnall, Preston Gubballs, Merrington, •of Salop, and terminating at or near to the town Uffington, Hodnett, Weston-under-Red-Castle, More- of Wem either by a distinct terminus or by a ton Corbett, Preston, Brockhurst, Shawbury, Acton junction with the Shropshire Union Railway, or Reynold, Besford, Edgbolton otherwise Edgebolt, any other railway or railways, at Wem, in the said Muckleton, Preston, Brockhurst, Shawbury, Wythe- county of Salop, with all proper works and con- ford Magna, Wytheford Parva, Wem, Aston, Cotton, veniences connected therewith respectively, and Edstaston, Horton, Lacon, Lowe and Ditches, New- which said railway or railways are intended to pass town, Northwood, Sleap, Soulton, Tilley and French from, in, through, or into the several following otherwise Tilley and Trench, Wem, Wolverley other- parishes, townships, and extra-parochial or other wise Woolverley, Lee Brockhurst, Prees, Whixall, places, or some of them (that is to say), Saint Mary, Harcourt, Harcout, Harcout Mill, Tilstock, Atcham, Sun and Ball, Coton otherwise Cotton Hill, Castle Saint Julian, Meole -

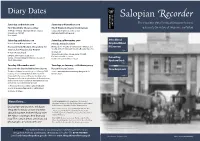

Salopian Recorder No.92

Diary Dates The newsletter of the Friends of Shropshire Archives, Saturday 20 October 2018 Saturday 17 November 2018 ARCHIVES First World War Showcase Day Much Wenlock Charter Celebrations SHROPSHIRE gateway to the history of Shropshire and Telford 10.00am - 4.00pm Shirehall, Abbey Foregate, Contact Much Wenlock Town Council Shrewsbury SY2 6ND www.muchwenlock-tc.gov.uk Free event! Saturday 27 October 2018 Saturday 24 November 2018 Arthur Allwood, Victoria County History Annual lecture Friends Annual Lecture Shropshire RHA and Horses in Early Modern Shropshire: for Dr Kate Croft - “Healthy and Expedient”: Childcare and KSLI, 1912-1919 Charity at the Shrewsbury Foundling Hospital 1759-1772 Service, for Pleasure, for Power? Page 2 Professor Peter Edwards 10.30am, £5 Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury, SY1 2AQ 2.00pm, £5 donation requested For further details see www. Reasearching Central, Shrewsbury Baptist Church, 4 Claremont friendsofshropshirearchives.org.uk Street, Shrewsbury Myndtown Church Page 5 Tuesday 6 November 2018 Tuesdays, 22 January – 26 February 2019 Discover the Stories Behind the Stones House History Course Shrewsbury at work The Beautiful Burial Ground project is offering a FREE Contact [email protected] for training session at Shropshire Archives for those further details interested in the stories told by our burial grounds. Page 8 This session will cover an introduction to the archive as well as how to use the archive to investigate the lives and stories in your local burial ground. To book your free place please get in touch with George at [email protected] or 01588 673041 10.30am - 12.30pm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The newsletter of the Friends of News Extra.. -

Tna Prob 11/27/408

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/27/408 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the will, dated 27 November 1538 and proved 1 February 1539, of Roger Corbet (1501/2 – 20 December 1538), ward of John de Vere (1442-1513), 13th Earl of Oxford, and uncle of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), the owner of a copy of Hall’s Chronicle containing annotations thought to have been made by Shakespeare. The volume was Loan 61 in the British Library until 2007, was subsequently on loan to Lancaster University Library until 2010, and is now in the hands of a trustee, Lady Hesketh. According to the Wikipedia entry for Sir Richard Newport, the annotated Hall’s Chronicle is now at Eton College, Windsor. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Newport_(died_1570) Newport's copy of his chronicle, containing annotations sometimes attributed to William Shakespeare, is now in the Library at Eton College, Windsor. For the annotated Hall’s Chronicle, see also the will of Sir Richard Newport (d. 12 September 1570), TNA PROB 11/53/456; Keen, Alan and Roger Lubbock, The Annotator, (London: Putnam, 1954); and the Annotator page on this website: http://www.oxford-shakespeare.com/annotator.html FAMILY BACKGROUND For the testator’s family background, see the pedigree of Corbet in Burke, John, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. III, (London: Henry Colburn, 1836), pp. 189-90 at: https://archive.org/stream/genealogicalhera03burk#page/188/mode/2up See also the pedigree of Corbet in Grazebrook, George, and John Paul Rylands, eds., The Visitation of Shropshire Taken in the Year 1623, Part I, (London: Harleian Society, 1889), Vol. -

Geoffrey of Monmouth and Medieval Welsh Historical Writing

Chapter 9 The Most Excellent Princes: Geoffrey of Monmouth and Medieval Welsh Historical Writing Owain Wyn Jones A late 14th-century manuscript of Brut y Brenhinedd (“History of the Kings”), the Welsh translation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s De gestis Britonum, closes with a colophon by the scribe, Hywel Fychan, Hywel Fychan ap Hywel Goch of Buellt wrote this entire manuscript lest word or letter be forgotten, on the request and command of his master, none other than Hopcyn son of Tomos son of Einion … And in their opinion, the least praiseworthy of those princes who ruled above are Gwrtheyrn and Medrawd [Vortigern and Mordred]. Since because of their treachery and deceit and counsel the most excellent princes were ruined, men whose descendants have lamented after them from that day until this. Those who suffer pain and subjection and exile in their native land.1 These words indicate the central role Geoffrey’s narrative had by this point as- sumed not only in vernacular historical writing, but also in the way the Welsh conceived of their past and explained their present. Hywel was writing around the time of the outbreak of Owain Glyn Dŵr’s revolt, and the ethnic and co- lonial grievances which led to that war are here articulated with reference to the coming of the Saxons and the fall of Arthur.2 During the revolt itself, Glyn Dŵr’s supporters justified his cause with reference to the Galfridian past, for 1 Philadelphia, Library Company of Philadelphia, 8680.O, at fol. 68v: “Y llyuyr h6nn a yscri- uenn6ys Howel Vychan uab Howel Goch o Uuellt yn ll6yr onys g6naeth agkof a da6 geir neu lythyren, o arch a gorchymun y vaester, nyt amgen Hopkyn uab Thomas uab Eina6n … Ac o’e barn 6ynt, anuolyannussaf o’r ty6yssogyon uchot y llywyassant, G6rtheyrn a Medra6t.