1 the Curtain Rises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Hike Leader Handbook

Excursions Committee New Hampshire Chapter Of the Appalachian Mountain Club Hike Leader Handbook February, 2016 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 2 of 75. 2AMC–NH Chapter Excursions Committee Hike Leader Handbook Table of Contents Letter to New Graduates The Trail to Leadership – Part D Part 1 - Leader Requirements Part 2 – Hike Leader Bill of Rights Part 2a-Leader-Participant Communication Part 3 - Guidelines for Hike Leaders Part 4 - Hike Submission Procedures Part 5 – On-line Hike Entry Instructions (AMC Database) Part 5a – Meetup Posting Instructions Part 6 – Accident & Summary of Use Report Overview Part 7 - AMC Incident Report Form Part 8 - WMNF Use Report Form Part 9 - Excursions Committee Meetings Part 10 - Mentor Program Overview Part 11 – Leader Candidate Requirements Part 12 - Mentor Requirements Part 13 - Mentor Evaluation Form Part 14 - Class 1 & 2 Peaks List Part 15 - Class 3 Peaks List Part 16 - Liability Release Form Instructions Part 17 - Release Form FAQs Part 18 - Release Form Part 19 - Activity Finance Policy Part 20 - Yahoo Group Part 21 – Leadership Recognition Part 22 – Crosswalk between Classes and Committees NH AMC Excursion Committee Bylaws Page 1 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 3 of 75. Page 2 of 2 AMC-NH Hike Leader Handbook Page 4 of 75. Hello, Leadership Class Graduate! We hope that you enjoyed yourself at the workshop, and found the weekend worthwhile. We also hope that you will consider becoming a NH Chapter AMC Hike leader—you’ll be a welcome addition to our roster of leaders, and will have a fun and rewarding experience to boot! About the Excursions Committee: We are the hikers in the New Hampshire Chapter, and we also lead some cycling hikes. -

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

Download It FREE Today! the SKI LIFE

SKI WEEKEND CLASSIC CANNON November 2017 From Sugarbush to peaks across New England, skiers and riders are ready to rock WELCOME TO SNOWTOPIA A experience has arrived in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. grand new LINCOLN, NH | RIVERWALKRESORTATLOON.COM Arriving is your escape. Access snow, terrain and hospitality – as reliable as you’ve heard and as convenient as you deserve. SLOPESIDE THIS IS YOUR DESTINATION. SKI & STAY Kids Eat Free $ * from 119 pp/pn with Full Breakfast for Two EXIT LoonMtn.com/Stay HERE Featuring indoor pool, health club & spa, Loon Mountain Resort slopeside hot tub, two restaurants and more! * Quad occupancy with a minimum two-night Exit 32 off I-93 | Lincoln, NH stay. Plus tax & resort fee. One child (12 & under) eats free with each paying adult. May not be combined with any other offer or discount. Early- Save on Lift Tickets only at and late-season specials available. LoonMtn.com/Tickets A grand new experience has arrived in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Arriving is your escape. Access snow, terrain and hospitality – as reliable as you’ve heard and as convenient as you deserve. SLOPESIDE THIS IS YOUR DESTINATION. SKI & STAY Kids Eat Free $ * from 119 pp/pn with Full Breakfast for Two EXIT LoonMtn.com/Stay HERE Featuring indoor pool, health club & spa, Loon Mountain Resort slopeside hot tub, two restaurants and more! We believe that every vacation should be truly extraordinary. Our goal Exit 32 off I-93 | Lincoln, NH * Quad occupancy with a minimum two-night stay. Plus tax & resort fee. One child (12 & under) is to provide an unparalleled level of service in a spectacular mountain setting. -

Green Hills Preserve

GREEN HILLS PRESERVE Welcome to the White Mountains’ Backyard reaching views of the Presidential Range, have been a popular White Mountains destination for well over a century. ENJOY THE PRESERVE RESPONSIBLY Trail Map & Guide You are about to enter a vast, 12,000-acre block of unfragmented This area is open to the public for recreation and education. forest—home to black bear, warblers and other wildlife. The Nature In the early 1900s, the Green Hills raged with wildfires, kindled by Conservancy, Town of Conway and State of New Hampshire have logging slash piles and sparks from timber trains. The fires helped to Please, for the protection of this area and its inhabitants: partnered to protect much of this land for public benefit. It’s an sustain a rare natural community known as “red pine rocky ridge,” extraordinary conservation success story and a place beloved by locals a hardy habitat adapted to fire, drought, wind and winter ice. You’ll • Leave No Trace—please keep the preserve and visitors alike. see some of this 700-acre community (the largest in the state) atop clean by carrying out your trash. Middle and Peaked mountains. Look for even-aged stands of red pine • Snowmobiles are allowed on designated (seeded during the fires) with a sparse, glade-like understory. History of the Green Hills multi-use trails only. All other motorized use is prohibited. Long ago, the Green Hills were town “common land,” where settlers • Mountain biking is allowed on designated had rights to hunt, graze their farm animals and cut firewood. In the 1800s, the town sold the land to private owners, but fortunately for trails, but is prohibited anywhere on “foot those interested in conservation, most of the Green Hills remained travel only” sections of the trail system. -

Appendix B: Habitats

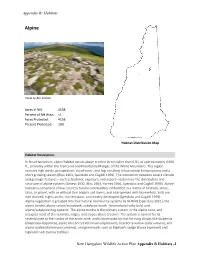

Appendix B: Habitats Alpine Photo by Ben Kimball Acres in NH: 4158 Percent of NH Area: <1 Acres Protected: 4158 Percent Protected: 100 Habitat Distribution Map Habitat Description In New Hampshire, alpine habitat occurs above treeline (trees taller than 6 ft.) at approximately 4,900 ft., primarily within the Franconia and Presidential Ranges of the White Mountains. This region endures high winds, precipitation, cloud cover, and fog, resulting in low annual temperatures and a short growing season (Bliss 1963, Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). The interaction between severe climate and geologic features—such as bedrock, exposure, and aspect—determine the distribution and structure of alpine systems (Antevs 1932, Bliss 1963, Harries 1966, Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Alpine habitat is comprised of low, treeless tundra communities embedded in a matrix of bedrock, stone, talus, or gravel, with or without thin organic soil layers, and interspersed with krummholz. Soils are well drained, highly acidic, nutrient poor, and weakly developed (Sperduto and Cogbill 1999). Alpine vegetation is grouped into four natural community systems by NHNHB (Sperduto 2011): the alpine tundra, alpine ravine/snowbank, subalpine heath ‐ krummholz/rocky bald, and alpine/subalpine bog systems. The alpine tundra is the primary system in the alpine zone, and occupies most of the summits, ridges, and slopes above treeline. The system is named for its resemblance to the tundra of the arctic zone, and is dominated by mat‐forming shrubs like diapensia (Diapensia lapponica), alpine blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum), bearberry willow (Salix uvaursi), and alpine‐azalea (Kalmia procumbens), and graminoids such as Bigelow's sedge (Carex bigelowii) and highland rush (Juncus trifidus). -

Green Hills Preserve

bedrock formed roughly 200 million years ago. Redstone Ledge, Trail, which is blazed in blue. At 0.4 miles, the Peaked Mountain Black Cap Connector Trail – 4 miles. This trail connects the trails Rattlesnake, Middle and Peaked Mountains show a distinctive “stoss- Connector Trail, a means to access the Black Cap Connector Trail, of Black Cap, Peaked and Middle Mountains. Blazed in yellow, it and-lee” topography. In profile, the northwestern slopes of these diverges left. From here, bear right and continue up exposed granite begins at a junction with the Black Cap trail 0.8 miles from Hurricane peaks gradually ascend to their summits then precipitously drop on slabs with intermittent stands of red pine and pitch pine, eventually Mountain Road and ends at the junction of the Middle Mountain/ the southeast side. This feature formed as the last continental glacier reaching a false summit and past a junction with the Peaked-Middle Pudding Pond trails. At 0.3 miles, the Black Cap Connector Trail gently scoured the northwestern slopes on its approach, then removed Mountain Connector Trail. A steep climb for 0.2 miles east ends on (0.2 miles) goes left to the summit of Black Cap. At 1.9 miles, the extensive amounts of bedrock as it crested over the summits. On the the summit with excellent views of Middle Mountain, Black Cap, Mt. Mason Brook snowmobile trail diverges left. From this junction, the exposed bedrock on Peaked Mountain, there are also many examples Chocorua and the Moat Mountain Range. trail descends steeply and crosses a small brook, then reaches the of glacial polish, chatter marks and striations. -

New Hampshire Wildlife Action Plan Appendix B Habitats -1 Appendix B: Habitats

Appendix B: Habitats Appendix B: Habitat Profiles Alpine ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Appalachian Oak Pine Forest ........................................................................................................................ 9 Caves and Mines ......................................................................................................................................... 19 Grasslands ................................................................................................................................................... 24 Hemlock Hardwood Pine Forest ................................................................................................................. 34 High Elevation Spruce‐Fir Forest ................................................................................................................. 45 Lowland Spruce‐Fir Forest .......................................................................................................................... 53 Northern Hardwood‐Conifer Forest ........................................................................................................... 62 Pine Barrens ................................................................................................................................................ 72 Rocky Ridge, Cliff, and Talus ...................................................................................................................... -

Trip-Idea-Presidential-Range.Pdf

D I S TANCE: 115 MILES ➧ HIGHLIGHTS: FOUR STATE PARKS, NUMEROUS SCENIC V I S TAS, HISTORIC VILLAGES, HIKING TRAILS Snow-capped Mt. Washington rises above the rest of the Presidential Range and the foliage covered slopes below. Photo: Roland Bergeron The Presidential Range Tour offers exceptional views of the White Mountains, with access to abundant year-round recreational opportunities. LITTLETON TO LANCASTER. and take a historic walking tour along Continuing south, be sure to check Crawford Station; Crawford Notch State This 115 mile trail begins in Littleton Main Street. out Appalachian Mountain Club’s Park; and the Mount Washington Hotel, and follows NH 116 north to ALONG ROUTE 2. Following Pinkham Notch Visitors Center, one of the region’s foremost grand Whitefield. In Whitefield it follows Route 2 through Jefferson and which offers trail information, hotels. Also keep an eye out for the US 3 north to Lancaster. While on US Randolph, the full scope of the restroom facilities, lodging and meals. Conway Scenic Railroad train which 3 take a side trip to Weeks State Park impressive Presidentials will come The Wildcat Mt. Ski Area is also weaves its way through Crawford and Mt. Prospect. Weeks State Park is into view. On a clear day you can see nearby offering spectacular views of Notch during the warmer months. As the gateway to Mountain Road, the smoke rising from the Cog Mt. Washington, and year-round you head back towards Littleton, the another Scenic & Cultural Byway. Railway as it heads up the western recreational opportunities. route continues along through the small Along this park route you will be side of Mt. -

Presidentials Hike

Presidentials – White Mountains – Carroll, NH Length Difficulty Streams Views Solitude Camping 21.4 mls Hiking Time: 2.5 Days Elev. Gain: 7,800 ft Parking: Parking is near the AMC Highland Center Lodge. The Presidential Range in the White Mountains of NH is a true bucket list hike. Hiking above treeline for most of the hike will give some of the best views we have seen in the Eastern U.S. Make no mistake, it will take some effort to get to those views and then you can enjoy the hospitality of AMC's famous White Mountain Huts at the end of each day. There is also the potential for severe weather year round so go prepared. This is one hike you should put on your bucket list! Hike Notes: Parking is near the AMC Highland Center Lodge with a shuttle to the trailhead. See end of write up for additional information and logistics regarding this hike. Day 1 – 10.8 miles Mile 0.0 – The trail begins at the Webster /AT Trailhead (1300') on Route 302 about 4 miles from the AMC Highland Center. Head North to begin your climb to Mt Webster. This was some of the toughest 3 miles we have done with over 2600' of elevation gain before reaching Mt Webster. I don't remember any switchbacks! Mile 3.3 – Mt Webster summit (3910'), enjoy some great views of Crawford Notch. The Webster Jackson Trail (Webster Branch) comes in on the left, continue on the Webster Cliff Trail/AT. Mile 4.6 – Mt Jackson summit (4052'). -

THE COHOS TREKKER the Newsletter of the Cohos Trail Association

JANUARY 2018 VOLUME 20, ISSUE 1 THE COHOS TREKKER The Newsletter of The Cohos Trail Association LOGS ON: NEW NEIL TILLOTSON SHELTER IS UP AND RUNNING PITTSBURG – About half way along the pathway that is the Round Pond Brook Trail on the CT, a long-awaited log shelter donated by John Ninenger of Vermont Log Homes was erected so hikers might have a place to bed down for the night between the distant Lake Francis State Campground and the Deer Mountain State Campground in this huge 300,000- acre township at the top of the state. In June, volunteers fabricated what is now known as the Neil Tillotson Hut lean-to, named for the late centenarian patriarch of Dixville Notch who founded Tillotson Rubber Company and owned and operated Round Pond Brook Road for northbounders. From the Balsams Grand Resort Hotel. On a bit of forested either of the state campgrounds, the shelter can be level ground in the southwest corner of the reached within eight hours or less under most Connecticut Lakes State Park, the shelter was pulled circumstances. together with the help of as many as twenty people Much of the ancillary materials were donated, over the course of two and a half days. including the green metal roof and screws. It was a Today, the shelter is accompanied by a gift of Pride Roofing of Raymond, NH. The composting latrine fabricated by Jack Pepau and his foundation blocks were donated by an anonymous son, Chad. The privy is the first of its kind on the Cohos Trail fan.