Traded Commodities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German North Sea Ports' Absorption Into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914

From Unification to Integration: The German North Sea Ports' absorption into Imperial Germany, 1866–1914 Henning Kuhlmann Submitted for the award of Master of Philosophy in History Cardiff University 2016 Summary This thesis concentrates on the economic integration of three principal German North Sea ports – Emden, Bremen and Hamburg – into the Bismarckian nation- state. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Emden, Hamburg and Bremen handled a major share of the German Empire’s total overseas trade. However, at the time of the foundation of the Kaiserreich, the cities’ roles within the Empire and the new German nation-state were not yet fully defined. Initially, Hamburg and Bremen insisted upon their traditional role as independent city-states and remained outside the Empire’s customs union. Emden, meanwhile, had welcomed outright annexation by Prussia in 1866. After centuries of economic stagnation, the city had great difficulties competing with Hamburg and Bremen and was hoping for Prussian support. This thesis examines how it was possible to integrate these port cities on an economic and on an underlying level of civic mentalities and local identities. Existing studies have often overlooked the importance that Bismarck attributed to the cultural or indeed the ideological re-alignment of Hamburg and Bremen. Therefore, this study will look at the way the people of Hamburg and Bremen traditionally defined their (liberal) identity and the way this changed during the 1870s and 1880s. It will also investigate the role of the acquisition of colonies during the process of Hamburg and Bremen’s accession. In Hamburg in particular, the agreement to join the customs union had a significant impact on the merchants’ stance on colonialism. -

2018-2019 E-Mail

Fußballfachwarte NFV Kreis Cuxhaven Stand 18 .0 3 .201 9 Altherren, Altsenioren, Frauen 2018 - 201 9 Edgar Zander, Heerstr. 74, 27478 Cuxhaven TSV Altenbruch 01052002 Telefon privat: 04722 - 2323, Mobil: 0162 - 9797327 E - Mail: [email protected], Fax: 04722 - 2323 Jürgen Blohm, Hauptstr. 98 c, 27478 Cuxhaven TSV Altenwalde 01052004 Telefon privat: 04723 - 500499, Mobil: 0157 - 81982075 SG Altenwalde /Wanna/Lüdingworth Ü40 E - Mail: [email protected] Lars Milkert , Udendorfer Teil 71 , 27478 Cuxhaven TSV Altenwalde 01052004 Telefon p rivat: 04722 - 910420, Mobil: 0176 - 43840747 Frauen E - Mail: [email protected], Fax: 047422 - 910421 Rolf Diekmann , Bruchweg 26, 21734 Oederquart FC Basbeck - Osten 01052015 Telefon priv at: 04779 - 8994702, Mobil: 0152 - 56401531 E - Mail: rolf.die c kmann@gmx. net Jörn Struzyna , Auf dem Grad 28 , 27616 Beverstedt SG Beverstedt 01052030 Telefon privat: 04747 - 872874, Mobil: 015 2 - 56461266 E - Mail: [email protected] Stephan Niemeyer, Lehdebergstr. 100, 27616 Beverstedt MTV Bokel 01052040 Telefon privat: 04748 - 406058, Mobil: 0171 - 9102035 E - Mail: [email protected] Ralf Döscher, Danziger Str. 3, 21745 Hemmoor SV Bornberg 01052050 Telefon privat: 04771 - 8238, Mobil: 0170 - 3511009 E - Mail: [email protected] Tim Kliesch, Posener Str. 12, 27570 Bremerhaven TSV Bramel 0105 2060 Mobil: 0172 - 1922222 E - Mail: [email protected] Sascha Skowron, Pastorentrift 7, 21775 O disheim SG Bülkau / Steinau/ Odisheim 01052080 Mobil: 0160 - 1598458 E - Mail: [email protected] -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

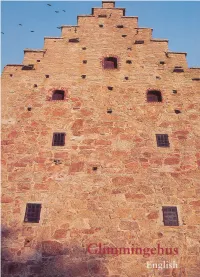

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

The Chemical Ecology of Host Plant Associated Speciation in the Pea Aphid (Acyrthosiphon Pisum) (Homoptera: Aphididae)

The chemical ecology of host plant associated speciation in the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) (Homoptera: Aphididae) By: David Peter Hopkins A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Sciences Departments of Animal and Plant Sciences October 2015 Table of Contents List of figures .......................................................................................................................... v List of tables .......................................................................................................................... viii Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... ix Abstract .................................................................................................................................... x Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. xi Chapter 1: General overview .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Host race ecological divergence and speciation .......................................................... 2 1.2 A. pisum as a model system for studying ecological divergence of host-specialist races ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2.1 Evidence that plant chemistry -

SENIORENWEGWEISER Älter Werden Im Cuxland

SENIORENWEGWEISER Älter werden im Cuxland www.landkreis-cuxhaven.de Wichtige Rufnummern auf einen Blick Feuerwehr/Rettungsdienst/Notarzt 112 Polizei/Notruf 110 Ärztlicher Bereitschaftsdienst 116 117 Augenärztlicher Bereitschaftsdienst 0 41 41 - 98 17 87 Apotheken-Notdienst 0800 - 002 28 33 Telefonseelsorge 0800 - 1 11 01 11 (bundesweit, kostenlos, 24 Stunden täglich) Wer meldet? Was ist passiert? Wo ist es passiert? Wie viele Personen sind beteiligt? Warten auf Rückfragen! Inhaltsverzeichnis Grußwort des Landrates 2.5 Sicherheit und Oberbürgermeisters ................................ 3 Seniorinnen und Senioren als (mögliche) Grußwort der Vorsitzenden des Verbrechensopfer ............................................ 11 Seniorenbeirates und des Vorsitzenden Polizeidienststellen .......................................... 11 1 des Beirates für Inklusion ............................... 4 Verkehrssicherheitsberatung .......................... 12 Hilfen für Kriegsopfer und Opfer von 1. Wir über uns Gewalttaten ...................................................... 12 Der Seniorenbeirat stellt sich vor .......................... 5 Der Beirat für Inklusion stellt sich vor ................... 6 2.6 Mobilität Der Senioren- und Pflegestützpunkt Öffentlicher Personennahverkehr (ÖPNV) ..... 12 Niedersachsen im Landkreis Cuxhaven Anrufsammeltaxi (AST) ................................... 13 stellt sich vor .................................................... 6 Fahrgemeinschaften ........................................ 13 Cuxland Infoline .............................................. -

Fund Og Forskning I Det Kongelige Biblioteks Samlinger

Særtryk af FUND OG FORSKNING I DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEKS SAMLINGER Bind 50 2011 With summaries KØBENHAVN 2011 UDGIVET AF DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEK Om billedet på papiromslaget se s. 169. Det kronede monogram på kartonomslaget er tegnet af Erik Ellegaard Frederiksen efter et bind fra Frederik III’s bibliotek Om titelvignetten se s. 178. © Forfatterne og Det Kongelige Bibliotek Redaktion: John T. Lauridsen med tak til Ivan Boserup Redaktionsråd: Ivan Boserup, Grethe Jacobsen, Else Marie Kofod, Erland Kolding Nielsen, Anne Ørbæk Jensen, Stig T. Rasmussen, Marie Vest Fund og Forskning er et peer-reviewed tidsskrift. Papir: Lessebo Design Smooth Ivory 115 gr. Dette papir overholder de i ISO 9706:1994 fastsatte krav til langtidsholdbart papir. Grafisk tilrettelæggelse: Jakob Kyril Meile Nodesats: Niels Bo Foltmann Tryk og indbinding: SpecialTrykkeriet, Viborg ISSN 0060-9896 ISBN 978-87-7023-085-8 JOHANN ADOLPH SCHEIBE (1708–76) and Copenhagen1 by Peter Hauge ohann Adolph Scheibe, a proponent of the galant style and indeed Jan influential music critic in the late eighteenth century, was a writer on aesthetics, music theory and performance practice, a translator and a composer. Though he wrote a vast amount of music this part of his creative production has to a large extent been neglected by mod- ern scholarship. His reputation today is mainly focused on his famous critique of J.S. Bach’s compositional style which he characterised as ‘bombastic and confused’, and his assertion that Bach darkened the beauty of the music ‘by an excess of art’ (that is, writing and making use of excessive ornamentation) and difficult to perform.2 It should be kept in mind, however, that though Scheibe admired the music of compos- ers such as G.Ph. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Register Für Die Jahrgänge 101-125 (1983-2007)1 1. Nachrufe Und

Hansische Geschichtsblätter Register für die Jahrgänge 101-125 (1983-2007)1 bearbeitet von Volker Henn 1. Nachrufe und Gedenken Assmann, Erwin, 1908-1984, von Erich Hoffmann: 103 (1985), lf. Dollinger, Philippe, 1904-1999, von Antjekathrin Graßmann: 119 (2001), 1-3. Ennen, Edith, 1907-1999, von Volker Henn: 118 (2000), 5-7. Förster, Leonard Wilson, 1913-1997, von Klaus Friedland: 116 (1998), Vf. Haase, Carl, 1920-1990, von Klaus Friedland: 108 (1990), S. Vf. Harder-Gersdorff, Elisabeth, 1932-2005, von Antjekathrin Graß mann: 124 (2006), V-IX. Jeannin, Pierre, 1924-2004, von Marie-Louise Pelus-Kaplan: 122 (2004), V-VIII. Kellenbenz, Hermann, 1913-1990, von Klaus Friedland und Rolf Wal ter: 109 (1991), Vf. Koppe, Wilhelm, 1908-1986, von Klaus Friedland: 104 (1986), 1-3. Lehe, Erich von, 1894-1983, von Karl H. Schwebel: 102 (1984), 1-3. Mollat du Jourdin, Michel, 1911-1996, von Ingeborg Heinsius: 116 (1998), VII. Oliveira Marques, A. H. de, von Thomas Denk: 125 (2007), V-VII. Schildhauer, Johannes, 1918-1995, von Walter Stark: 113 (1995), S. 1-5. Schneider, Gerhard, von Klaus Friedland: 106 (1988), 1-3. Schwebel, Karl H., 1911-1992, von Herbert Schwarzwälder: 111 (1993), V-VII. Skyum Nielsen, Niels, 1921-1982, von Erich Hoffmann: 101 (1983), 1-3. Stoob, Heinz, 1919-1997, von Wilfried Ehbrecht: 115 (1997), V-XI. 1 Das Register knüpft an das in den HGbll. 100, 1982, S. 297-311. veröffentlichte Regis- ter für die Jgg. 1963-1982 an. Die in jedem Band der HGbll. abgedruckten Jahres- und Rechnungsberichte des HGV sowie die Listen der Vorstandsmitglieder des Vereins sind unberücksichtigt geblieben. -

Ambassadors to and from England

p.1: Prominent Foreigners. p.25: French hostages in England, 1559-1564. p.26: Other Foreigners in England. p.30: Refugees in England. p.33-85: Ambassadors to and from England. Prominent Foreigners. Principal suitors to the Queen: Archduke Charles of Austria: see ‘Emperors, Holy Roman’. France: King Charles IX; Henri, Duke of Anjou; François, Duke of Alençon. Sweden: King Eric XIV. Notable visitors to England: from Bohemia: Baron Waldstein (1600). from Denmark: Duke of Holstein (1560). from France: Duke of Alençon (1579, 1581-1582); Prince of Condé (1580); Duke of Biron (1601); Duke of Nevers (1602). from Germany: Duke Casimir (1579); Count Mompelgart (1592); Duke of Bavaria (1600); Duke of Stettin (1602). from Italy: Giordano Bruno (1583-1585); Orsino, Duke of Bracciano (1601). from Poland: Count Alasco (1583). from Portugal: Don Antonio, former King (1581, Refugee: 1585-1593). from Sweden: John Duke of Finland (1559-1560); Princess Cecilia (1565-1566). Bohemia; Denmark; Emperors, Holy Roman; France; Germans; Italians; Low Countries; Navarre; Papal State; Poland; Portugal; Russia; Savoy; Spain; Sweden; Transylvania; Turkey. Bohemia. Slavata, Baron Michael: 1576 April 26: in England, Philip Sidney’s friend; May 1: to leave. Slavata, Baron William (1572-1652): 1598 Aug 21: arrived in London with Paul Hentzner; Aug 27: at court; Sept 12: left for France. Waldstein, Baron (1581-1623): 1600 June 20: arrived, in London, sightseeing; June 29: met Queen at Greenwich Palace; June 30: his travels; July 16: in London; July 25: left for France. Also quoted: 1599 Aug 16; Beddington. Denmark. King Christian III (1503-1 Jan 1559): 1559 April 6: Queen Dorothy, widow, exchanged condolences with Elizabeth. -

Hansische Geschichtsblätter

Hansische Geschichtsblätter K ö n ig r e ic h E n g la n d Herausgegeben vom Hansischen Geschichtsverein Porta Alba 129. Jahrgang 2011 Verlag HANSISCHE GESCHICHTSBLÄTTER HERAUSGEGEBEN VOM HANSISCHEN GESCHICHTSVEREIN 129. JAHRGANG 2011 Porta Alba Verlag Trier REDAKTION Aufsatzteil: Prof. Dr. Rolf Hammel-Kiesow, Lübeck Umschau: Dr. Volker Herrn, Kordel Für besondere Zuwendungen und erhöhte Jahresbeiträge, ohne die dieser Band nicht hätte erscheinen können, hat der Hansische Geschichtsverein folgenden Stiftungen, Verbänden und Städten zu danken: P o s s e h l -S t if t u n g z u L ü b e c k F reie u n d H a n s e s t a d t H a m b u r g F r e ie H a n s e s t a d t B r e m e n H a n s e s t a d t L ü b e c k Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe D r . M a r g a r e t e S c h in d l e r , B u x t e h u d e Umschlagabbildung nach: Hanseraum und Sächsischer Städtebund im Spätmittelal ter, in: Hanse, Städte. Bünde. Die sächsischen Städte zwischen Elbe und Weser, Bd. 1, hg. v. Matthias Puhle, Magdeburg 1996, S. 3. Zuschriften, die den Aufsatzteil betreffen, sind zu richten an Herrn Prof. Dr. Rolf H a m m e l -K ie s o w , Archiv der Hansestadt Lübeck, Mühlendamm 1-3, 23552 Lübeck ([email protected]); Besprechungsexemplare und sonstige Zuschrif ten wegen der Hansischen Umschau an Herrn Dr. -

A Bibliography of 17Th Century German Imprints in Denmark and the Duchies of Schleswig-Holstein

A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF 17TH CENTURY GERMAN IMPRINTS IN DENMARK AND THE DUCHIES OF SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN By P. M. MITCHELL Volume 1 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES 1969 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PUBLICATIONS Library Series, 28 A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF 17TH CENTURY GERMAN IMPRINTS IN DENMARK AND THE DUCHIES OF SCHLESWIG^HOLSTEIN By P. M. MITCHELL Volume 1 UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES 1969 COPYRIGHT 1969 BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES Library of Congress catalog card number : 66-64214 PRINTED IN LAWRENCE, KANSAS, U.S.A. BY THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PRINTING SERVICE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IN PREPARING THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY I HAVE BENEFITED FROM THE ASSISTANCE AND GOOD OFFICES OF MANY INDIVIDUALS AND INSTITUTIONS. MY GREATEST DEBT IS TO THE ROYAL LIBRARY IN COPENHAGEN, WHERE, FROM FIRST TO LAST, I HAVE DRAWN ON THE COUNSELS AND ENVIABLE HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE OF DR. RICHARD PAULLI. MESSRS. PALLE BIRKE- LUND, ERIK DAL, AND MOGENS HAUGSTED AS WELL AS MANY OTHER MEMBERS OF THE STAFF OF THE ROYAL LIBRARY CHEERFULLY SOUGHT TO MEET MY SPECIAL NEEDS FOR A DECADE. THE COOPERATION OF DR. OTFRIED WEBER, MR. WOLFGANG MERCKENS, AND MR. KARL-HEINZ TIEDEMANN OF THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF KIEL HAS BEEN EXEM• PLARY. DR. OLAF KLOSE OF THE SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEINISCHE LANDESBIBLIOTHEK KINDLY ARRANGED MY VISITS TO SEVERAL PRIVATE LIBRARIES, WHERE I WAS HOSPITABLY RECEIVED. I HAVE ENJOYED SPECIAL PRIVILEGES NOT ONLY IN COPENHAGEN AND KIEL BUT ALSO AT THE LIBRARY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM, THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF COPEN• HAGEN, THE HERZOG AUGUST BIBLIOTHEK IN WOLFENBÜTTEL, THE ROYAL LIBRARY IN STOCKHOLM, AND THE STAATSBIBLIOTHEK IN MUNICH. -

University of Tarty Faculty of Philosophy Department of History

UNIVERSITY OF TARTY FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY LINDA KALJUNDI Waiting for the Barbarians: The Imagery, Dynamics and Functions of the Other in Northern German Missionary Chronicles, 11th – Early 13th Centuries. The Gestae Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum of Adam of Bremen, Chronica Slavorum of Helmold of Bosau, Chronica Slavorum of Arnold of Lübeck, and Chronicon Livoniae of Henry of Livonia Master’s Thesis Supervisor: MA Marek Tamm, Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales / University of Tartu Second supervisor: PhD Anti Selart University of Tartu TARTU 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 I HISTORICAL CONTEXTS AND INTERTEXTS 5 I.1 THE SOURCE MATERIAL 5 I.2. THE DILATATIO OF LATIN CHRISTIANITY: THE MISSION TO THE NORTH FROM THE NINTH UNTIL EARLY THIRTEENTH CENTURIES 28 I.3 NATIONAL TRAGEDIES, MISSIONARY WARS, CRUSADES, OR COLONISATION: TRADITIONAL AND MODERN PATTERNS IN HISTORIOGRAPHY 36 I.4 THE LEGATIO IN GENTES IN THE NORTH: THE MAKING OF A TRADITION 39 I.5 THE OTHER 46 II TO DISCOVER 52 I.1 ADAM OF BREMEN, GESTA HAMMABURGENSIS ECCLESIAE PONTIFICUM 52 PERSONAE 55 LOCI 67 II.2 HELMOLD OF BOSAU, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 73 PERSONAE 74 LOCI 81 II.3 ARNOLD OF LÜBECK, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 86 PERSONAE 87 LOCI 89 II.4 HENRY OF LIVONIA, CHRONICON LIVONIAE 93 PERSONAE 93 LOCI 102 III TO CONQUER 105 III.1 ADAM OF BREMEN, GESTA HAMMABURGENSIS ECCLESIAE PONTIFICUM 107 PERSONAE 108 LOCI 128 III.2 HELMOLD OF BOSAU, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 134 PERSONAE 135 LOCI 151 III.3 ARNOLD OF LÜBECK, CHRONICA SLAVORUM 160 PERSONAE 160 LOCI 169 III.4 HENRY OF LIVONIA, CHRONICON LIVONIAE 174 PERSONAE 175 LOCI 197 SOME CONCLUDING REMARKS 207 BIBLIOGRAPHY 210 RESÜMEE 226 APPENDIX 2 Introduction The following thesis discusses the image of the Slavic, Nordic, and Baltic peoples and lands as the Other in the historical writing of the Northern mission.