Ignatius, the Popes, and Realistic Reverence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews on Trial: the Papal Inquisition in Modena

1 Jews, Papal Inquisitors and the Estense dukes In 1598, the year that Duke Cesare d’Este (1562–1628) lost Ferrara to Papal forces and moved the capital of his duchy to Modena, the Papal Inquisition in Modena was elevated from vicariate to full Inquisitorial status. Despite initial clashes with the Duke, the Inquisition began to prosecute not only heretics and blasphemers, but also professing Jews. Such a policy towards infidels by an organization appointed to enquire into heresy (inquisitio haereticae pravitatis) was unusual. In order to understand this process this chapter studies the political situation in Modena, the socio-religious predicament of Modenese Jews, how the Roman Inquisition in Modena was established despite ducal restrictions and finally the steps taken by the Holy Office to gain jurisdiction over professing Jews. It argues that in Modena, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Holy Office, directly empowered by popes to try Jews who violated canons, was taking unprecedented judicial actions against them. Modena, a small city on the south side of the Po Valley, seventy miles west of Ferrara in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, originated as the Roman town of Mutina, but after centuries of destruction and renewal it evolved as a market town and as a busy commercial centre of a fertile countryside. It was built around a Romanesque cathedral and the Ghirlandina tower, intersected by canals and cut through by the Via Aemilia, the ancient Roman highway from Piacenza to Rimini. It was part of the duchy ruled by the Este family, who origi- nated in Este, to the south of the Euganean hills, and the territories it ruled at their greatest extent stretched from the Adriatic coast across the Po Valley and up into the Apennines beyond Modena and Reggio, as well as north of the Po into the Polesine region. -

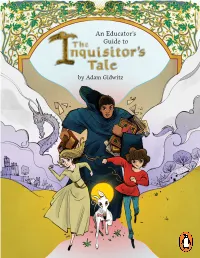

An Educator's Guide To

An Educator’s Guide to by Adam Gidwitz Dear Educator, I’m at the Holy Crossroads Inn, a day’s walk north of Paris. Outside, the sky is dark, and getting darker… It’s the perfect night for a story. Critically acclaimed Adam Gidwitz’s new novel has “as much to say about the present as it does the past.” (— Publishers Weekly). Themes of social justice, tolerance and empathy, and understanding differences, especially as they relate to personal beliefs and religion, run through- out his expertly told tale. The story, told from multiple narrator’s points of view, is evocative of The Canterbury Tales—richly researched and action packed. Ripe for 4th-6th grade learners, it could be read aloud or assigned for at-home or in-school reading. The following pages will guide you through teaching the book. Broken into sections and with suggested links and outside source material to reference, it will hopefully be the starting point for you to incorporate this book into the fabric of your classroom. We are thrilled to introduce you to a new book by Adam, as you have always been great champions of his books. Thank you for your continued support of our books and our brand. Penguin School & Library About the Author: Adam Gidwitz taught in Brooklyn for eight years. Now, he writes full- time—which means he writes a couple of hours a day, and lies on the couch staring at the ceiling the rest of the time. As is the case with all of this books, everything in them not only happened in the real fairy tales, it also happened to him. -

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY the Roman Inquisition and the Crypto

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Peter Akawie Mazur EVANSTON, ILLINOIS June 2008 2 ABSTRACT The Roman Inquisition and the Crypto-Jews of Spanish Naples, 1569-1582 Peter Akawie Mazur Between 1569 and 1582, the inquisitorial court of the Cardinal Archbishop of Naples undertook a series of trials against a powerful and wealthy group of Spanish immigrants in Naples for judaizing, the practice of Jewish rituals. The immense scale of this campaign and the many complications that resulted render it an exception in comparison to the rest of the judicial activity of the Roman Inquisition during this period. In Naples, judges employed some of the most violent and arbitrary procedures during the very years in which the Roman Inquisition was being remodeled into a more precise judicial system and exchanging the heavy handed methods used to eradicate Protestantism from Italy for more subtle techniques of control. The history of the Neapolitan campaign sheds new light on the history of the Roman Inquisition during the period of its greatest influence over Italian life. Though the tribunal took a place among the premier judicial institutions operating in sixteenth century Europe for its ability to dispense disinterested and objective justice, the chaotic Neapolitan campaign shows that not even a tribunal bearing all of the hallmarks of a modern judicial system-- a professionalized corps of officials, a standardized code of practice, a centralized structure of command, and attention to the rights of defendants-- could remain immune to the strong privatizing tendencies that undermined its ideals. -

Dreams of Al-Andalus; a Survey of the Illusive Pursuit of Religious Freedom in Spain

Dreams of al-Andalus; A Survey of the Illusive Pursuit of Religious Freedom in Spain By Robert Edward Johnson Baptist World Alliance Seville, Spain July 10, 2002 © 2002 by the American Baptist Quarterly a publication of the American Baptist Historical Society, P.O. Box 851, Valley forge, PA 19482-0851. Around 1481, a local chronicler from Seville narrated a most incredible story centering around one of the city’s most prominent citizens, Diego de Susán. He was among Seville’s wealthiest and most influential citizens, a councilor in city government, and, perhaps most important, he was father to Susanna—the fermosa fembra (“beautiful maiden”). He was also a converso, and was connected with a group of city merchants and leaders, most of whom were conversos as well. All were opponents to Isabella’s government. According to this narration, Susán was at the heart of a plot to overthrow the work of the newly created Inquisition. He summoned a meeting of Seville’s power brokers and other rich and powerful men from the towns of Utrera and Carmona. These said to one another, ‘What do you think of them acting thus against us? Are we not the most propertied members of this city, and well loved by the people? Let us collect men together…’ And thus between them they allotted the raising of arms, men, money and other necessities. ‘And if they come to take us, we, together with armed men and the people will rise up and slay them and so be revenged on our enemies.’[1] The fly in the ointment of their plans was the fermosa fembra herself. -

Manresa and Saint Ignatius of Loyola

JOAN SEGARRA PIJUAN was born in Tárrega, Spain on June 29, 1926. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1942. Seventeen years later he completed his religious and cultural education. On July 29, 1956 – in the Year of Saint Ignatius – he was ordained at the cathedral in Manresa. He has spent much of his life in Veruela, Bar- celona, Sant Cugat del Vallès, Palma (Majorca), Raimat, Rome and Man- resa and has also lived in a number of countries in Central and South Ameri- ca, Africa and Europe. He has always been interested in spi- ritual theology and the study of Saint Ignatius of Loyola. SAINT IGNA- TIUS AND MANRESA describes the Saint’s sojourn here in a simple, rea- dable style. The footnotes and exten- sive bibliography will be of particular interest to scholars wishing the study the life of St. Ignatius in greater de- tail. This book deals only with the months Saint Ignatius spent in Man- resa, which may have been the most interesting part of his life: the months of his pilgrimage and his mystical en- lightenments. Manresa is at the heart of the Pilgrim’s stay in Catalonia because “between Ignatius and Man- resa there is a bond that nothing can break” (Torras y Bages). A copy of this book is in the Library at Stella Maris Generalate North Foreland, Broadstairs, Kent, England CT10 3NR and is reproduced on line with the permission of the author. AJUNTAMENT DE MANRESA Joan Segarra Pijuan, S.J. 1st edition: September 1990 (Catalan) 2nd edition: May 1991 (Spanish) 3rd edition: September 1992 (English) © JOAN SEGARRA i PIJUAN, S.J. -

Spanish Persecution of the 15Th-17Th Centuries: a Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels Laura Ledray Hamline University

Hamline University DigitalCommons@Hamline Departmental Honors Projects College of Liberal Arts Spring 2016 Spanish Persecution of the 15th-17th Centuries: A Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels Laura Ledray Hamline University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/dhp Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Ledray, Laura, "Spanish Persecution of the 15th-17th Centuries: A Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels" (2016). Departmental Honors Projects. 51. https://digitalcommons.hamline.edu/dhp/51 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts at DigitalCommons@Hamline. It has been accepted for inclusion in Departmental Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Hamline. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 Spanish Persecution of the 15th-17th Centuries: A Study of Discrimination Against Witches at the Local and State Levels Laura Ledray An Honors Thesis Submitted for partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in History from Hamline University 4/24/2016 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction_________________________________________________________________________________________3 Historiography______________________________________________________________________________________8 Origins of the Spanish Inquisition_______________________________________________________________15 Identifying -

The Motivation for the Patronage of Pope Julius Ii

THE MOTIVATION FOR THE PATRONAGE OF POPE JULIUS II Christine Shaw As the head of the Western Church, Giuliano della Rovere, Pope Julius II (1503-13), has had his critics, from his own day to ours, above all for his role as ‘the warrior pope’. The aspect of his rule that has won most general approval has been his patronage of the arts. The complex iconography of some of the works Julius commissioned, particularly Raphael’s frescoes in the Vatican Stanze, and the scale of some of the projects he initiated – the rebuilding of St Peter’s, the development of the via Giulia, the massive and elaborate tomb Michelangelo planned to create for him – have provided fertile soil for interpretation of these works as expressions of Julius’s own ideals, aspirations, motives and self-image. Too fertile, perhaps – some interpretations have arguably become over-elaborate and recherchés. The temptation to link the larger than life character of Julius II with the claims for the transcendent power and majesty of the papacy embodied in the ico- nography and ideology of the works of art and writings produced in Rome during his pontificate, whether or not they were commissioned by the pope, has often proved irresistible to scholars. Some of the works associated with Julius can be read as expressions of certain conceptions of papal authority, and of the Rome of the Renaissance popes as the culmination of classical and Jewish, as well as early Christian history. But should they be read as Julius’s conception of his role as pope, his programme for his own papacy? Just because others identified him with Julius Caesar, or with Moses, does that mean that he saw himself as Moses, as a second Julius Caesar? There were plenty of learned men in Rome, ready to elabore theories of papal power which drew on different traditions and to fit Julius into them, just as they had fitted earlier popes and would fit later popes into them. -

Your Name Here

ILLUMINATING HERETICS: ALUMBRADOS AND INQUISITION IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY CUENCA by JESSICA FOWLER (Under the Direction of Benjamin Ehlers) ABSTRACT This thesis delves into two cases of alumbradismo brought before the Spanish Inquisition in the archbishopric of Cuenca, during the 1590s. The fact that the cases of Juana Rubia and Francisco de los Reyes exist breaks with historiographical understandings of alumbrados and thus forces historians to reconsider the heresy at large. INDEX WORDS: Alumbrados, Cuenca, Spanish Inquisition, Heresy, Spain ILLUMINATING HERETICS: ALUMBRADOS AND INQUISITION IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY CUENCA by JESSICA FOWLER B.A., Appalachian State University, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2009 © 2009 Jessica Fowler All Rights Reserved ILLUMINATING HERETICS: ALUMBRADOS AND INQUISITION IN SIXTEENTH CENTURY CUENCA by JESSICA FOWLER Major Professor: Benjamin Ehlers Committee: Pamela Voekel Michael Kwass Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2009 DEDICATION To my mother, Jackie Fowler, who would support me even if I said I wanted to fly to the moon. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This particular project would never have been possible without the chance to conduct research in Spain. For this opportunity I must thank the Department of History, who reached as deeply as possible into its all too shallow pockets; the Bartley Foundation and its selection committee for believing in the potential of both myself and my thesis; and the Graduate Dean of Arts and Science who so generously agreed to purchase my airfare. -

Reconquista and Spanish Inquisition

Name __________________________________________ Date ___________ Class _______ Period _____ The Reconquista and the Spanish Inquisition by Jessica Whittemore (education-portal.com) Directions: Read the article and answer the questions in full sentences. Muslim Control Of Spain The Reconquista and especially the Inquisition encompass one of the darkest times in Spanish history. It was a time when faith, greed and politics combined to bring about the deaths of many. Let's start with the Spanish Reconquista. In simpler terms, the Reconquista was the attempt by Christian Spain to expel all Muslims from the Iberian Peninsula. In the 8th century, Spain was not one united nation but instead a group of kingdoms. In the early 8th century, these kingdoms of Spain were invaded by Muslim forces from North Africa. Within a few years of this invasion, most of Spain was under Muslim control. In fact, the Muslims renamed the Spanish kingdoms Al- Andalus or Andalusia, but for our purposes, we're going to stick with Spain. Since the Muslims were an advanced society, Spain prospered. The Muslims were also very tolerant of other religions, allowing Muslims, Christians and Jews to basically take up the same space. However, Muslim political leaders were very suspicious of one another, which led to disunity among the many kingdoms. This disunity opened up the doors for Christian rule to seep in, and while the Muslims kept firm control of the southern kingdoms of Granada, Christian power began taking hold in the northern kingdoms of Aragon, Castile and Navarre. By the end of the 13th century, only Granada remained under Muslim control. -

Martin Luther’S New Doctrine of Salvation That Resulted in a Break from the Catholic Church and the Establishment of Lutheranism

DO NOW WHAT DOES THE WORD REFORM MEAN? WHAT DO YOU THINK IT MEANS REGARDING THE CHURCH? Learning Targets and Intentions of the Lesson I Want Students To: 1. KNOW the significance of Martin Luther’s new doctrine of salvation that resulted in a break from the Catholic church and the establishment of Lutheranism. 2. UNDERSTAND the way humanism and Erasmus forged the Reformation. 3. Analyze (SKILL) how Calvinism replaced Lutheranism as the most dynamic form of Protestantism. Essential Question. What caused the Protestant Reformation? REFORMATION RE FORM TO DO TO MAKE AGAIN BUT DO OVER/MAKE WHAT AGAIN?THE CHURCH! Definitions Protest Reform To express strong To improve by objection correcting errors The Protestant Reformation 5 Problems in the Church • Corruption • Political Conflicts Calls for Reform • John Wycliffe (1330-1384) – Questioned the authority of the pope • Jan Hus (1370-1415) – Criticized the vast wealth of the Church • Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) – Attacked corruption in the Church Corruption • The Church raised money through practices like simony and selling indulgences. Advantages of Buying Indulgences Go Directly to Heaven! • Do not go to Hell! • Do not go to Purgatory! • Get through Purgatory faster! • Do not pass Go! Martin Luther Who was Martin Luther? • Born in Germany in 1483. • After surviving a violent storm, he vowed to become a monk. • Lived in the city of Wittenberg. • Died in 1546. Luther Looks for Reforms • Luther criticized Church practices, like selling indulgences. • He wanted to begin a discussion within the Church about the true path to salvation. • Stresses faith over He nailed his Ninety- works, rejected church Five Theses, or as intermediary. -

Assembling Alumbradismo: the Evolution of a Heretical Construct1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital.CSIC Assembling Alumbradismo 251 Chapter 9 Assembling Alumbradismo: The Evolution of a Heretical Construct1 Jessica J. Fowler The heresy of Alumbradismo is far from an unknown topic of study, but it remains one of the most confusing terms in Spanish historiography.2 It has appeared in general studies of the Spanish Inquisition since the beginning of the twentieth century.3 An increasing interest in this heresy as part of, and contributing to, a broader and more nuanced assessment of the Spanish spiri- tual climate of the sixteenth century produced a number of important articles in the mid-twentieth century.4 Larger studies of these specific heretics and their beliefs would appear beginning in the late 1970s.5 This trend was quickly followed by efforts to make the inquisitorial documents dealing with Alum- 1 The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) ERC Grant Agreement number 323316, project CORPI ‘Conversion, Overlapping Religiosities, Polemics, Interaction. Early Modern Iberia and Beyond’. The author would also like to thank the tutors and participants of the 2015 Summer Academy of Atlantic History for their com- ments and suggestions on this paper. 2 Alison Weber, ‘Demonizing Ecstasy: Alonso de la Fuente and the Alumbrados of Extremadura’, in The Mystical Gesture: Essays on Medieval and Early Modern Spiritual Culture in Honor of Mary E. Giles, (ed.) Robert Boenig (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), p.