The Life and Works of the Purpose of This Monograph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

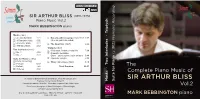

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MARK BEBBINGTON Piano Riptych

SOMMCD 0148 DDD Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) Céleste Series Piano Music Vol.2 MArK BEBBiNGtON piano riptych t Masks (1924) · 1 A Comedy Mask 1:21 bl Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (1932) 2:57 2 A Romantic Mask 3:50 (The old year has ended) Première Recording 3 A Sinister Mask 2:22 bm The Rout Trot (1927) 2:42 4 A Military Mask 2:53 Triptych (1970) Two Interludes (1925) .1912) bn Meditation: Andante tranquillo 7:08 5 c No. 1 4:09 bo ( Dramatic Recitative: 6 nterludes No. 2 3:23 Grave – poco a poco molto animato 5:48 i bp Suite for Piano (c.1912) Capriccio: allegro 5:09 Première Recording bq wo 7 ‛Bliss’ (One-Step) (1923) 3:15 Prelude 5:47 t The 8 Ballade 7:48 Total Duration: 62:11 · 9 Scherzo 3:32 Complete Piano Music of Recorded at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, 3rd & 4th January 2011 Sir Arthur Bliss Steinway Concert Grand Model 'D' Masks Suite for Piano Recording Producer: Siva Oke Recording Engineer: Paul Arden-Taylor Vol.2 Front Cover photograph of Mark Bebbington: © Rama Knight Design & Layout: Andrew Giles © & 2015 SOMM RECORDINGS · THAMES DITTON · SURREY · ENGLAND MArK BEBBiNGtON piano Made in the EU THE SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF SIR ARTHUR BLISS Vol. 2 Anyone coming new to Bliss’s piano music via these publications might be forgiven for For anyone who has investigated the piano music of Arthur Bliss, the most puzzling thinking that the composer’s contribution to the repertoire was of little significance, aspect is surely that, as a body of work, it remains so little known. -

A Hundred Years of British Piano Miniatures Butterworth • Fricker • Harrison Headington • L

WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS A HUNDRED YEARS OF BRITISH PIANO MINIATURES BUTTERWORTH • FRICKER • HARRISON HEADINGTON • L. & E. LIVENS • LONGMIRE POWER • REYNOLDS • SKEMPTON • WARREN DUNCAN HONEYBOURNE A HUNDRED YEARS OF BRITISH PIANO MINIATURES BUTTERWORTH • FRICKER • HARRISON • HEADINGTON L. & E. LIVENS • LONGMIRE • POWER • REYNOLDS SKEMPTON • WARREN DUNCAN HONEYBOURNE, piano Catalogue Number: GP789 Recording Date: 25 August 2015 Recording Venue: The National Centre for Early Music, St Margaret’s Church, York, UK Producers: David Power and Peter Reynolds (1–21), Peter Reynolds and Jeremy Wells (22–28) Engineer: Jeremy Wells Editors: David Power and Jeremy Wells Piano: Bösendorfer 6’6” Grand Piano (1999). Tuned to modern pitch. Piano Technician: Robert Nutbrown Booklet Notes: Paul Conway, David Power and Duncan Honeybourne Publishers: Winthrop Rogers Ltd (1, 3), Joseph Williams Ltd (2), Unpublished. Manuscript from the Michael Jones collection (4), Comus Edition (5–7), Josef Weinberger Ltd (8), Freeman and Co. (9), Oxford University Press (10, 11), Unpublished. Manuscript held at the University of California Santa Barbara Library (12, 13), Unpublished (14–28), Artist Photograph: Greg Cameron-Day Cover Art: Gro Thorsen: City to City, London no 23, oil on aluminium, 12x12 cm, 2013 www.grothorsen.com LEO LIVENS (1896–1990) 1 MOONBEAMS (1915) 01:53 EVANGELINE LIVENS (1898–1983) 2 SHADOWS (1915) 03:15 JULIUS HARRISON (1885–1963) SEVERN COUNTRY (1928) 02:17 3 III, No. 3, Far Forest 02:17 CONSTANCE WARREN (1905–1984) 4 IDYLL IN G FLAT MAJOR (1930) 02:45 ARTHUR BUTTERWORTH (1923–2014) LAKELAND SUMMER NIGHTS, OP. 10 (1949) 10:07 5 I. Evening 02:09 6 II. Rain 02:30 7 III. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst La Ttéiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’S Preludes for Piano Op.163 and Op.179: a Musicological Retrospective

NUI MAYNOOTH Ûllscôst la ttÉiîéann Mâ Üuad Charles Villiers Stanford’s Preludes for Piano op.163 and op.179: A Musicological Retrospective (3 Volumes) Volume 1 Adèle Commins Thesis Submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare 2012 Head of Department: Professor Fiona M. Palmer Supervisors: Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley & Dr Patrick F. Devine Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to a number of people who have helped me throughout my doctoral studies. Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation to my supervisors and mentors, Dr Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Dr Patrick Devine, for their guidance, insight, advice, criticism and commitment over the course of my doctoral studies. They enabled me to develop my ideas and bring the project to completion. I am grateful to Professor Fiona Palmer and to Professor Gerard Gillen who encouraged and supported my studies during both my undergraduate and postgraduate studies in the Music Department at NUI Maynooth. It was Professor Gillen who introduced me to Stanford and his music, and for this, I am very grateful. I am grateful to the staff in many libraries and archives for assisting me with my many queries and furnishing me with research materials. In particular, the Stanford Collection at the Robinson Library, Newcastle University has been an invaluable resource during this research project and I would like to thank Melanie Wood, Elaine Archbold and Alan Callender and all the staff at the Robinson Library, for all of their help and for granting me access to the vast Stanford collection. -

52183 FRMS Cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1

4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:25 Page 1 Autumn 2012 No. 157 £1.75 Bulletin 4884 cover_52183 FRMS cover 142 17/08/2012 09:21 Page 2 NEW RELEASES THE ROMANTIC VIOLIN STEPHEN HOUGH’S CONCERTO – 13 French Album Robert Schumann A master pianist demonstrates his Hyperion’s Romantic Violin Concerto series manifold talents in this delicious continues its examination of the hidden gems selection of French music. Works by of the nineteenth century. Schumann’s late works Poulenc, Fauré, Debussy and Ravel rub for violin and orchestra had a difficult genesis shoulders with lesser-known gems by but are shown as entirely worthy of repertoire their contemporaries. status in these magnificent performances by STEPHEN HOUGH piano Anthony Marwood. ANTHONY MARWOOD violin CDA67890 BBC SCOTTISH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CDA67847 DOUGLAS BOYD conductor MUSIC & POETRY FROM THIRTEENTH-CENTURY FRANCE Conductus – 1 LOUIS SPOHR & GEORGE ONSLOW Expressive and beautiful thirteenth-century vocal music which represents the first Piano Sonatas experiments towards polyphony, performed according to the latest research by acknowledged This recording contains all the major works for masters of the repertoire. the piano by two composers who were born within JOHN POTTER tenor months of each other and celebrated in their day CHRISTOPHER O’GORMAN tenor but heard very little now. The music is brought to ROGERS COVEY-CRUMP tenor modern ears by Howard Shelley, whose playing is the paradigm of the Classical-Romantic style. HOWARD SHELLEY piano CDA67947 CDA67949 JOHANNES BRAHMS The Complete Songs – 4 OTTORINO RESPIGHI Graham Johnson is both mastermind and Violin Sonatas pianist in this series of Brahms’s complete A popular orchestral composer is seen in a more songs. -

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets Of

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) By © 2017 Matthew Butterfield DMA, University of Kansas, 2017 M.M., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011 B.S., The Pennsylvania State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Dr. Colin Roust Dr. Sarah Frisof Dr. Eric Stomberg Dr. Michelle Hayes Date Defended: 2 May 2017 The dissertation committee for Matthew Butterfield certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Date Approved: 10 May 2017 ii Abstract Léon Goossens’s virtuosity, musicality, and developments in playing the oboe expressively earned him a reputation as one of history’s finest oboists. His artistry and tone inspired British composers in the early twentieth century to consider the oboe a viable solo instrument once again. Goossens became a very popular and influential figure among composers, and many works are dedicated to him. His interest in having new music written for oboe and strings led to several prominent pieces, the earliest among them being the oboe quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927). Bax’s music is strongly influenced by German romanticism and the music of Edward Elgar. This led critics to describe his music as old-fashioned and out of touch, as it was not intellectual enough for critics, nor was it aesthetically pleasing to the masses. -

Winter 2015 Programme

Winter 2015 programme Box Office 020 8463 0100 www.blackheathhalls.com Hire the Halls Blackheath Halls, a Grade II listed building, offers two beautiful and unique spaces for celebrations, performances, recordings, conferences and rehearsals. Renowned for the quality of its acoustics, the magnificent Great Hall is the venue of choice for leading orchestras and ensembles for recordings and rehearsals. Among those who choose Blackheath Halls as their preferred venue are Chandos Records, English National Opera, London Symphony Orchestra and Channel 4. The recently refurbished Recital Room, which is licensed for wedding ceremonies, offers the perfect location for smaller scale functions and chamber music performances. For all hire enquiries please contact Caroline Foulkes, [email protected] or 020 8318 9758 BLACKHEATH WELCOMESUNDAYS PLENTY TO KEEP YOU ENTERTAINED IN 2015 CONTENTS A Happy New Year to everyone. concert, including the wonderfully Blackheath Sundays Blackheath Halls has a great tradition for evocative Seven Last Words on the Cross bringing you some of the best names on by James MacMillan. This is a rare the comedy circuit. Following in that opportunity to see and hear one of the Classical events tradition, we are delighted to announce leading choral groups in the world. the launch of Laughing Boy Comedy Club, The Jette Parker Young Artists will a monthly Thursday night show in the present three further Wednesday evening Recital Room. Alongside new and recitals at the Halls, the first on 21 January. CoLab emerging comedy talents, the Comedy The students of Trinity Laban will once Club will feature some of the top again be providing a diverse range of comedians trying out new material. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

A GARLAND for JOHN MCCABE Monica Mccabe’S Reflections on a Life Lived for Music Agenda British Music Society’S News and Events British Music Scores Search

BRITISH MUSIC SOCIETY nAPRIL 2018 ews AMBASSADOR FOR BRITISH MUSIC IN USA Madeleine Mitchell across the pond A GARLAND FOR JOHN MCCABE Monica McCabe’s reflections on a life lived for music Agenda British Music Society’s news and events British music scores search org Schneider from the German for piano and winds (1890) wind ensemble Four Points One • George Alexander Osborne Chairman’s J(www.four-point-one.de) is on Quintet for piano and winds the hunt for scores the following (1889) (Yes - he is actually Irish) compositions by British composers: If anyone from the BMS welcome • Marian Arkwright Quintet for network could help him track down piano and winds these scores please get in touch with MS member Madeleine Mitchell is back • Edith Swepstone Quintet for him at [email protected]. piano and winds Jorg is also on the look out for from America and has submitted the first • Henry David Leslie Quintet for any information about the Sir BBMS Ambassador report from her visit to piano and winds op.6 Michael Costa Prize 1896 Anyone the Kansas State University (see opposite page). • Edward Davey Rendall Quintet know anything about this? The committee is closely monitoring the progress of this new scheme and are always interested to hear members’ views. Reviving Victorian opera For those of you with access to the internet, a visit to the BMS website now offers the preced - ictorian Opera Northwest to revise Nell Gwynne by inviting B have made full opera C Stevenson (a librettist of Sullivan’s ing Printed News that opens by clicking on the recordings of works by Balfe, The Zoo) to write the new book. -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

Download Booklet

557439bk Bax US 2/07/2004 11:02am Page 5 in mind some sort of water nymph of Greek vignette In a Vodka Shop, dated 22nd January 1915. It Ashley Wass mythological times.’ In a newspaper interview Bax illustrates, however, Bax’s problem trying to keep his himself described it as ‘nothing but tone colour – rival lady piano-champions happy, for Myra Hess gave The young British pianist, Ashley Wass, is recognised as one of the rising stars BAX changing effects of tone’. the first performance at London’s Grafton Galleries on of his generation. Only the second British pianist in twenty years to reach the In January 1915, at a tea party at the Corders, the 29th April 1915, and as a consequence the printed finals of the Leeds Piano Competition (in 2000), he was the first British pianist nineteen-year-old Harriet Cohen appeared wearing as a score bears a dedication to her. ever to win the top prize at the World Piano Competition in 1997. He appeared Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 and 2 decoration a single daffodil, and Bax wrote almost in the ‘Rising Stars’ series at the 2001 Ravinia Festival and his promise has overnight the piano piece To a Maiden with a Daffodil; been further acknowledged by the BBC, who selected him to be a New he was smitten! Over the next week two more pieces Generations Artist over two seasons. Ashley Wass studied at Chethams Music Dream in Exile • Nereid for her followed, the last being the pastiche Russian Lewis Foreman © 2004 School and won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music to study with Christopher Elton and Hamish Milne. -

The Musical Development of Arnold Bax

THE MUSICAL DEVELOPMENT OF ARNOLD BAX BY R. L. E. FOREMAN ONE of the most enjoyable of musical autobiographies is Arnold Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ml/article/LII/1/59/1326778 by guest on 30 September 2021 Bax's.1 Written in Scotland during the Second War, when he felt himself more or less unable to compose, it brilliantly evokes the composer's life up to the outbreak of the Great War, through a series of closely observed anecdotes. These include portraits of major figures of the time—Elgar, Parry, Mackenzie, Sibelius—making it an important source. Yet curiously enough, though it is the only extended account of any portion of Bax's life that we have, it is not very informative about the composer's musical development, although dealing very amusingly with individual episodes, such as the first performance of 'Christmas Eve on the Mountains'.* Until the majority of Bax's manuscripts were bequeathed to the British Museum by Harriet Cohen,' it was difficult to make even a full catalogue of his music. Now it is possible to trace much of his surviving juvenilia and early work and place it in the framework of the autobiography. In following the evolution of what was a very complex musical style during its developing years it is necessary to take into account both musical and non-musical influences. Bax's early musical influences were Wagner, Elgar, Strauss and Liszt—the latter he referred to as "the master of us all".* Later an important influence was the Russian National School, while other minor influences are noticeable in specific works, including Dvorak (particularly in the first string quartet) and Grieg (in the 'Symphonic Variations'). -

EVELYN BARBIROLLI, Oboe Assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, Harpsichord the SHEPHERD QUARTET

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Rice University EVELYN BARBIROLLI, oboe assisted by · ANNE SCHNOEBELEN, harpsichord THE SHEPHERD QUARTET Wednesday, October 20, 1976 8:30P.M. Hamman Hall RICE UNIVERSITY Samuel Jones, Dean I SSN 76 .10. 20 SH I & II TA,!JE I PROGRAM Sonata in E-Flat Georg Philipp Telernann Largo (1681 -1767) Vivace Mesto Vivace Sonata in D Minor Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach Allegretto (1732-1795) ~ndante con recitativi Allegro Two songs Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Das Lied der Trennung (1756-1791) _...-1 Vn moto di gioia mi sento (atr. Evelyn Rothwell) 71 u[J. 0...·'1. {) /llfil.A.C'-!,' l.raMc AI,··~ l.l. ' Les Fifres Jean Fra cois Da leu (1682-1738) (arr. Evelyn Rothwell) ' I TAPE II Intermission Quartet Massonneau Allegro madera to (18th Century French) Adagio ' Andante con variazioni Quintet in G Major for Oboe and Strings Arnold Bax Molto mo~erato - Allegro - Molto Moderato (1883-1953) Len to espressivo Allegro giocoso All meml!ers of the audiehce are cordially invited to a reception in the foyer honoring Lady Barbirolli following this evening's concert. EVELYN BARBIROLLI is internationally known as one of the few great living oboe virtuosi, and began her career th1-ough sheer chance by taking up the study qf her instrument at 17 because her school (Downe House, Newbury) needed an oboe player. Within a yenr, she won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. Evelyn Rothwell immediately establis71ed her reputation Hu·ough performances and recordings at home and abroad.