Tips & Tricks to Gothic Geometry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

The Digital Nature of Gothic

The Digital Nature of Gothic Lars Spuybroek Ruskin’s The Nature of Gothic is inarguably the best-known book on Gothic architecture ever published; argumentative, persuasive, passionate, it’s a text influential enough to have empowered a whole movement, which Ruskin distanced himself from on more than one occasion. Strangely enough, given that the chapter we are speaking of is the most important in the second volume of The Stones of Venice, it has nothing to do with the Venetian Gothic at all. Rather, it discusses a northern Gothic with which Ruskin himself had an ambiguous relationship all his life, sometimes calling it the noblest form of Gothic, sometimes the lowest, depending on which detail, transept or portal he was looking at. These are some of the reasons why this chapter has so often been published separately in book form, becoming a mini-bible for all true believers, among them William Morris, who wrote the introduction for the book when he published it First Page of John Ruskin’s “The with his own Kelmscott Press. It is a precious little book, made with so much love and Nature of Gothic: a chapter of The Stones of Venice” (Kelmscott care that one hardly dares read it. Press, 1892). Like its theoretical number-one enemy, classicism, the Gothic has protagonists who write like partisans in an especially ferocious army. They are not your usual historians – the Gothic hasn’t been able to attract a significant number of the best historians; it has no Gombrich, Wölfflin or Wittkower, nobody of such caliber – but a series of hybrid and atypical historians such as Pugin and Worringer who have tried again and again, like Ruskin, to create a Gothic for the present, in whatever form: revivalist, expressionist, or, as in my case, digitalist, if that is a word. -

Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic Example with a Plan That Resembles Romanesque

Gothic Art • The Gothic period dates from the 12th and 13th century. • The term Gothic was a negative term first used by historians because it was believed that the barbaric Goths were responsible for the style of this period. Gothic Architecture The Gothic period began with the construction of the choir at St. Denis by the Abbot Suger. • Pointed arch allowed for added height. • Ribbed vaulting added skeletal structure and allowed for the use of larger stained glass windows. • The exterior walls are no longer so thick and massive. Terms: • Pointed Arches • Ribbed Vaulting • Flying Buttresses • Rose Windows Video - Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and St. Denis Laon Cathedral • Early Gothic example with a plan that resembles Romanesque. • The interior goes from three to four levels. • The stone portals seem to jut forward from the façade. • Added stone pierced by arcades and arched and rose windows. • Filigree-like bell towers. Interior of Laon Cathedral, view facing east (begun c. 1190 CE). Exterior of Laon Cathedral, west facade (begun c. 1190 CE). Chartres Cathedral • Generally considered to be the first High Gothic church. • The three-part wall structure allowed for large clerestory and stained-glass windows. • New developments in the flying buttresses. • In the High Gothic period, there is a change from square to the new rectangular bay system. Khan Academy Video: Chartres West Facade of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Royal Portals of Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). Nave, Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France (begun 1134 CE, rebuilt after 1194 CE). -

Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World Readings

Readings Pages 114- 129 Great Architecture of the World ARCH 1121 HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL TECHNOLOGY Photo: Alexander Aptekar © 2009 Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Influenced by Romanesque Architecture While Romanesque remained solid and massive – Gothic: 1) opened up to walls with enormous windows and 2) replaced semicircular arch with the pointed arch. Style emerged in France Support: Piers and Flying Buttresses Décor: Sculpture and stained glass Effect: Soaring, vertical and skeleton-like Inspiration: Heavenly light Goal: To lift our everyday life up to the heavens Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Dominant Art during this time was Architecture Growth of towns – more prosperous They wanted their own churches – Symbol of civic Pride More confident and optimistic Appreciation of Nature Church/Cathedral was the outlet for creativity Few people could read and write Clergy directed the operations of new churches- built by laymen Gothic Architecture 1140-1420 Began soon after the first Crusaders returned from Constantinople Brought new technology: Winches to hoist heavy stones New Translation of Euclid’s Elements – Geometry Gothic Architecture was the integration of Structure and Ornament – Interior Unity Elaborate Entrances covered with Sculpture and pronounced vertical emphasis, thin walls pierced by stained-glass Gothic Architecture Characteristics: Emphasis on verticality Skeletal Stone Structure Great Showing of Glass: Containers of light Sharply pointed Spires Clustered Columns Flying Buttresses Pointed Arches Ogive Shape Ribbed Vaults Inventive Sculpture Detail Sharply Pointed Spires Gothic Architecture 1140-1500 Abbot Suger had the vision that started Gothic Architecture Enlargement due to crowded churches, and larger windows Imagined the interior without partitions, flowing free Used of the Pointed Arch and Rib Vault St. -

Circle Patterns in Gothic Architecture

Bridges 2012: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Circle patterns in Gothic architecture Tiffany C. Inglis and Craig S. Kaplan David R. Cheriton School of Computer Science University of Waterloo [email protected] Abstract Inspired by Gothic-influenced architectural styles, we analyze some of the circle patterns found in rose windows and semi-circular arches. We introduce a recursive circular ring structure that can be represented using a set-like notation, and determine which structures satisfy a set of tangency requirements. To fill in the gaps between tangent circles, we add Appollonian circles to each triplet of pairwise tangent circles. These ring structures provide the underlying structure for many designs, including rose windows, Celtic knots and spirals, and Islamic star patterns. 1 Introduction Gothic architecture, a style of architecture seen in many great cathedrals and castles, developed in France in the late medieval period [1, 3]. This majestic style is often applied to ecclesiastical buildings to emphasize their grandeur and solemnity. Two key features of Gothic architecture are height and light. Gothic buildings are usually taller than they are wide, and the verticality is further emphasized through towers, pointed arches, and columns. In cathedrals, the walls are often lined with large stained glass windows to introduce light and colour into the buildings. In the mid-18th century, an architectural movement known as Gothic Revival began in England and quickly spread throughout Europe. The Neo-Manueline, or Portuguese Final Gothic, developed under the influence of traditional Gothic architecture and the Spanish Plateresque style [10]. The Palace Hotel of Bussaco, designed by Italian architect Luigi Manini and built between 1888 and 1907, is a well-known example of Neo-Manueline architecture (Figure 2). -

2-A-07-10-Not13-Instructions- Build a Cathedral-HS.Docx

ART 2-07 lnstructions to Build Your Cathedral 1. Print out all six pages on cardstock. 2. Cut out on all solid lines. Dotted lines are fold lines. 3. Page one: The Crossing. This should look familiar. We used it on the squinches and pendentive lesson. a. Cut down the center of the paper, to separate the pointed pieces (piece A) from the large piece (piece B) that has four folds. b. Take piece A and carefully cut all the dark areas away. Throw these dark pieces away. c. Glue section C under section D. C and D are parts of a point. When glued they make a whole point. d. Glue or tape the fold down areas of the dome. There are two ways to do this. i. First way: start on the C/D point and put a very tiny bit of glue on the back of the fold down section. Then bring point E over to the C/D point. C/D should be under the E point. Continue putting glue on the back of the glued down section and bringing the next point over. You may have overlap. That is okay. Just glue all the points to the center. ii. Second way: put tape on the inside of the C/D point and then bring all the points up and stick to the tape. e. The four triangles on the bottom of the dome are the squinches or pendentives. Fold them out. Carefully crease this fold. f. Set dome aside. Piece B is the nave. This is where the people sit. -

Rayonnant Style, French Building Style (13Th Century) That Represents the Height of Gothic Architecture

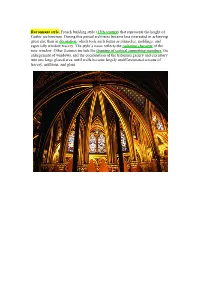

Rayonnant style, French building style (13th century) that represents the height of Gothic architecture. During this period architects became less interested in achieving great size than in decoration, which took such forms as pinnacles, moldings, and especially window tracery. The style’s name reflects the radiating character of the rose window. Other features include the thinning of vertical supporting members, the enlargement of windows, and the combination of the triforium gallery and clerestory into one large glazed area, until walls became largely undifferentiated screens of tracery, mullions, and glass. Flamboyant style, phase of late Gothic architecture in 15th-century France and Spain. It evolved out of the Rayonnant style’s increasing emphasis on decoration. Its most conspicuous feature is the dominance in stone window tracery of a flamelike S- shaped curve. Wall surface was reduced to the minimum to allow an almost continuous window expanse. Structural logic was obscured by covering buildings with elaborate tracery. Flamboyant Gothic, which became increasingly ornate, gave way in France to Renaissance forms in the 16th century. Perpendicular style, Phase of late Gothic architecture in England roughly parallel in time to the French Flamboyant style. The style, concerned with creating rich visual effects through decoration, was characterized by a predominance of vertical lines in stone window tracery, enlargement of windows to great proportions, and conversion of the interior stories into a single unified vertical expanse. Fan vaults, springing from slender columns or pendants, became popular. In the 16th century, the grafting of Renaissance elements onto the Perpendicular style resulted in the Tudor style. Manueline, Portuguese Manuelino, particularly rich and lavish style of architectural ornamentation indigenous to Portugal in the early 16th century. -

Rose Window Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Rose Window from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

6/19/2016 Rose window Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Rose window From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A rose window or Catherine window is often used as a generic term applied to a circular window, but is especially used for those found in churches of the Gothic architectural style and being divided into segments by stone mullions and tracery. The name “rose window” was not used before the 17th century and according to the Oxford English Dictionary, among other authorities, comes from the English flower name rose.[1] The term “wheel window” is often applied to a window divided by simple spokes radiating from a central boss or opening, while the term “rose window” is reserved for those windows, sometimes of a highly complex design, which can be seen to bear similarity to a multipetalled rose. Rose windows are also called Catherine windows after Saint Catherine of Alexandria who was sentenced to be executed on a spiked wheel. A circular Exterior of the rose at Strasbourg window without tracery such as are found in many Italian churches, is Cathedral, France. referred to as an ocular window or oculus. Rose windows are particularly characteristic of Gothic architecture and may be seen in all the major Gothic Cathedrals of Northern France. Their origins are much earlier and rose windows may be seen in various forms throughout the Medieval period. Their popularity was revived, with other medieval features, during the Gothic revival of the 19th century so that they are seen in Christian churches all over the world. Contents 1 History 1.1 Origin 1.2 The windows of Oviedo Interior of the rose at Strasbourg 1.3 Romanesque circular windows Cathedral. -

A Catholic Architect Abroad: the Architectural Excursions of A.M

A CATHOLIC ARCHITECT ABROAD: THE ARCHITECTURAL EXCURSIONS OF A.M. DUNN Michael Johnson Introduction A leading architect of the Catholic Revival, Archibald Matthias Dunn (1832- 1917) designed churches, colleges and schools throughout the Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle. Working independently or with various partners, notably Edward Joseph Hansom (1842-1900), Dunn was principally responsible for rebuilding the infrastructure of Catholic worship and education in North- East England in the decades following emancipation. Throughout his career, Dunn’s work was informed by first-hand study of architecture in Britain and abroad. From his first year in practice, Dunn was an indefatigable traveller, venturing across Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, filling mind and sketchbook with inspiration for his own designs. In doing so, he followed in the footsteps of Catholic travellers who had taken the Grand Tour, a tradition which has been admirably examined in Anne French’s Art Treasures in the North: Northern Families on the Grand Tour (2009).1 While this cultural pilgrimage was primarily associated with the landed gentry of the eighteen century, Dunn’s travels demonstrate that the forces of industrialisation and colonial expansion opened the world to the professional middle classes in the nineteenth century.2 This article examines Dunn’s architectural excursions, aiming to place them within the wider context of travel and transculturation in Victorian visual culture. Reconstructing his journeys from surviving documentary sources, it seeks to illuminate the processes by which foreign forms came to influence architectural taste during the ‘High Victorian’ phase of the Gothic Revival. Analysing Dunn’s major publication, Notes and Sketches of an Architect (1886), it uses contemporaneous reviews in the building press to determine how this illustrated record of three decades of international travel was received by the architectural establishment. -

Gothic Architecture

1 Gothic Architecture. The pointed Gothic arch is the secret of the dizzy heights the cathedral builders were able to achieve, from around the 13th Century. Columns became more slender, and vaults higher. Great open spaces and huge windows became the or- der of the day, as the pointed arch began to replace the rounded Roman-style arches of the Romanesque period. We will compare the two styles. On the left are the later arches of Salisbury Cathedral, c. 1230, in the Gothic style with elegant and slender piers. On the right are the Romanesque arches of Gloucester Cathedral with their huge cylindrical supports of faced stone filled with rubble, from around 1130. This is a drawing of praying hands by In this diagram Albrecht Dürer, you can see the 1508, in the effect of these Albertina Gallery in forces on a Gothic Vienna. If you hold pointed arch, your hands like this where some of the and imagine some- thrust is upwards, one pressing down alleviating part of on your knuckles, the weight of the you’ll feel your vault. finger ends move upwards. 2 There are different types of Gothic windows. Early English lancet windows, built 13th Century, plate tracery St. Dunstan’s Church, 1234, east end of Southwell Minster, in the south aisle west Canterbury. Early English Nottinghamshire, England window, All Saints Church, Decorated Style, 13th Hopton, Suffolk, England Century. The first structural windows with pointed arches were built in England and France, and be- gan with plain tall and thin shapes called lancets. By the 13th Century they were decorating the tops of the arches and piercing the stonework above with shapes such as this 4 leaf clover quatrefoil. -

1 Classical Architectural Vocabulary

Classical Architectural Vocabulary The five classical orders The five orders pictured to the left follow a specific architectural hierarchy. The ascending orders, pictured left to right, are: Tuscan, Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and Composite. The Greeks only used the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian; the Romans added the ‘bookend’ orders of the Tuscan and Composite. In classical architecture the selected architectural order for a building defined not only the columns but also the overall proportions of a building in regards to height. Although most temples used only one order, it was not uncommon in Roman architecture to mix orders on a building. For example, the Colosseum has three stacked orders: Doric on the ground, Ionic on the second level and Corinthian on the upper level. column In classical architecture, a cylindrical support consisting of a base (except in Greek Doric), shaft, and capital. It is a post, pillar or strut that supports a load along its longitudinal axis. The Architecture of A. Palladio in Four Books, Leoni (London) 1742, Book 1, plate 8. Doric order Ionic order Corinthian order The oldest and simplest of the five The classical order originated by the The slenderest and most ornate of the classical orders, developed in Greece in Ionian Greeks, characterized by its capital three Greek orders, characterized by a bell- the 7th century B.C. and later imitated with large volutes (scrolls), a fascinated shaped capital with volutes and two rows by the Romans. The Roman Doric is entablature, continuous frieze, usually of acanthus leaves, and with an elaborate characterized by sturdy proportions, a dentils in the cornice, and by its elegant cornice. -

AP Art History Chapter 13: Gothic Art Mrs. Cook

AP Art History Chapter 13: Gothic Art Mrs. Cook Define these terms: Key Cultural & Religious Terms: Scholasticism, disputatio, indulgences, lux nova, Annunciation, Visitation, opere francigeno, opus modernum Key Art Terms: stained glass, glazier, flashing, cames, leading, plate tracery, bar tracery, fleur‐de‐lis, Rayonnant, Flamboyant, mullions, moralized Bible, breviary, Perpendicular style, ambo, altarpiece, triptych, pieta Key Architectural Terms: altar frontal, rib vault, armature, webs, pointed arch, jamb figures, trumeau, triforium, oculus, flying buttress, pinnacle, vaulting web, diagonal rib, transverse rib, springing, clerestory, lancet, nave arcade, compound pier (cluster pier), shafts (responds), ramparts, battlements, crenellations, merlons, crenels, fan vaults, pendants, Gothic Revival, Hallenkirche (hall church) Exercises for Study: 1. Describe the key architectural features introduced in the French cathedral design in the Gothic era. 2. Describe features that make English Gothic cathedrals distinct from their French or German counterparts. 3. Describe the late Gothic Rayonnant and Flamboyant styles, and give examples of each. 4. Compare and contrast the following pairs of artworks, using the points of comparison as a guide. A. Old Testament kings and queen, jamb statues, Chartres Cathedral (Fig. 13‐7); Virgin and Child (Virgin of Paris), Notre‐Dame, Paris (Fig. 13‐26) • Dates: • Composition/posture of figures: • Relation to architecture: B. Saint Theodore, jamb statue, left portal, Porch of the Martyrs, Chartres Cathedral (Fig. 13‐18); Naumburg Master, Ekkehard and Uta, Naumburg Cathedral (Fig. 13‐48): • Dates: • Subjects: • Composition/posture of figures: • Relation to architecture: C. Interior of Saint Elizabeth, Marburg, Germany (Fig. 13‐53); Interior of Laon Cathedral, Laon, France (Fig. 13‐9) • Dates & locations: • Nave elevation: • Aisles: • Ceiling vaults: • Other architectural features: Chapter Questions: 1.