Notes and Doamients Downloaded from Burgundian Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorials of Old Dorset

:<X> CM \CO = (7> ICO = C0 = 00 [>• CO " I Hfek^M, Memorials of the Counties of England General Editor : Rev. P. H. Ditchfield, M.A., F.S.A. Memorials of Old Dorset ?45H xr» MEMORIALS OF OLD DORSET EDITED BY THOMAS PERKINS, M.A. Late Rector of Turnworth, Dorset Author of " Wimborne Minster and Christchurch Priory" ' " Bath and Malmesbury Abbeys" Romsey Abbey" b*c. AND HERBERT PENTIN, M.A. Vicar of Milton Abbey, Dorset Vice-President, Hon. Secretary, and Editor of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club With many Illustrations LONDON BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.C. AND DERBY 1907 [All Rights Reserved] TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD EUSTACE CECIL, F.R.G.S. PAST PRESIDENT OF THE DORSET NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTIQUARIAN FIELD CLUB THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY HIS LORDSHIP'S KIND PERMISSION PREFACE editing of this Dorset volume was originally- THEundertaken by the Rev. Thomas Perkins, the scholarly Rector of Turnworth. But he, having formulated its plan and written four papers therefor, besides gathering material for most of the other chapters, was laid aside by a very painful illness, which culminated in his unexpected death. This is a great loss to his many friends, to the present volume, and to the county of for Mr. Perkins knew the as Dorset as a whole ; county few men know it, his literary ability was of no mean order, and his kindness to all with whom he was brought in contact was proverbial. After the death of Mr. Perkins, the editing of the work was entrusted to the Rev. -

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.Net

St. Edward the Martyr Catholic.net Edward the Martyr (Old English: Eadweard; c. 962 – 18 March 978) was King of England from 975 until he was murdered in 978. Edward was the eldest son of King Edgar the Peaceful but was not his father's acknowledged heir. On Edgar's death, the leadership of England was contested, with some supporting Edward's claim to be king and others supporting his much younger half-brother Æthelred the Unready, recognized as a legitimate son of Edgar. Edward was chosen as king and was crowned by his main clerical supporters, the archbishops Dunstan and Oswald of Worcester. The great nobles of the kingdom, ealdormen Ælfhere and Æthelwine, quarrelled, and civil war almost broke out. In the so-called anti-monastic reaction, the nobles took advantage of Edward's weakness to dispossess the Benedictine reformed monasteries of lands and other properties that King Edgar had granted to them. Edward's short reign was brought to an end by his murder at Corfe Castle in 978 in circumstances that are not altogether clear. His body was reburied with great ceremony at Shaftesbury Abbey early in 979. In 1001 Edward's remains were moved to a more prominent place in the abbey, probably with the blessing of his half-brother King Æthelred. Edward was already reckoned a saint by this time. A number of lives of Edward were written in the centuries following his death in which he was portrayed as a martyr, generally seen as a victim of the Queen Dowager Ælfthryth, mother of Æthelred. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering -

Parish News Page 2

Anglican Catholic Church of St Augustine Eastling Road, Painters Forstal, Kent ME13 0DU P ARISH N EWS Sunday: 11 am Sung Mass (1st Sunday: Healing Service) Holy Days: As Announced A Very Warm Today, in our Mask Wearing & Social Distancing Apply Kalendar, in addi- WELCOME tion to celebrating the Third Sunday This Sunday is after Trinity, we commemorate the Translation of the Relics of St Trinity III (Comm: Edward. King and Martyr. But what do we Translation of St Edward) mean by this? 20th June 2021 The translation of relics is the removal of holy objects associated with a The Propers of the Saint (or perhaps the Saint’s remains themselves) from one locality to another Mass begin on (usually a higher-status location); usually Page 587 of the red only the movement of the remains of the Book of Common Prayer saint's body would be treated so formally, with secondary relics such as and Page C59 of the items of clothing, treated with less Anglican Missal ceremony. Translations could be accompanied by many acts, including all-night vigils and processions, often involving entire communities. Often in the early Middle Ages However, Edward's short reign was solemn translation marked the moment at brought to an end by his murder at Corfe which, the saint's miracles having been Castle. Initially buried there, St Edwards recognized, the relic was moved by a relics were translated first on 13th bishop or abbot to a prominent position February 981 to the great Abbey in within the church. Local veneration was Shaftesbury. -

Edward the Martyr

Edward the Martyr From OrthodoxWiki The holy and right-believing King Edward the Martyr (c. 962 – March 18, 978/979) succeeded his father Edgar of England as King of England in 975, but was murdered after a reign of only a few years. As the murder was attributed to "irreligious" opponents, whereas Edward himself was considered a good Christian, he was glorified as Saint Edward the Martyr in 1001; he may also be considered a passion-bearer. His feast day is celebrated on March 18, the uncovering of his relics is commemorated on February 13, and the elevation of his relics on June 20. The translation of his relics is commemorated on September 3. St. Edward the Martyr Contents 1 Motive and details of his murder 2 History of his relics 3 See also 4 Source 5 External links Motive and details of his murder Edward's accession to the throne was contested by a party headed by his stepmother, Queen Elfrida, who wished her son, Ethelred the Unready, to become king instead. However, Edward's claim had more support—including that of St. Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury—and was confirmed by the Witan. King Edward "was a young man of great devotion and excellent conduct. He was completely Orthodox, good and of holy life. Moreover, he loved God and the Church above all things. He was generous to the poor, a haven to the good, a champion of the Faith of Christ, a vessel full of every virtuous grace." On King Edward's accession to the throne a great famine was raging through the land and violent attacks were stirred up against monasteries by prominent noblemen who coveted the lands that his father King Edgar had endowed to them. -

162912442.Pdf

Emily Mitchell Patronage and Politics at Barking Abbey, c. 950 - c. 1200 Abstract This thesis is a study of the Benedictine abbey of Barking in Essex from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. It is based on a wide range of published and unpublished documentary sources, and on hagiographie texts written at the abbey. It juxtaposes the literary and documentary sources in a new way to show that both are essential for a full understanding of events, and neither can be fully appreciated in isolation. It also deliberately crosses the political boundary of 1066, with the intention of demonstrating that political events were not the most significant determinant of the recipients of benefactors’ religious patronage. It also uses the longer chronological scale to show that patterns of patronage from the Anglo-Saxon era were frequently inherited by the incoming Normans along with their landholdings. Through a detailed discussion of two sets of unpublished charters (Essex Record Office MSS D/DP/Tl and Hatfield, Hatfield House MS Ilford Hospital 1/6) 1 offer new dates and interpretations of several events in the abbey’s history, and identify the abbey’s benefactors from the late tenth century to 1200. As Part III shows, it has been possible to trace patterns of patronage which were passed down through several generations, crossing the political divide of 1066. Royal patronage is shown to have been of great significance to the abbey, and successive kings exploited their power of advowson in different ways according to the political atmosphere o f England. The literary sources are discussed in a separate section, but with full reference to the historical narrative. -

Lives of the British Saints

LIVES OF THE BRITISH SAINTS Vladimir Moss Copyright: Vladimir Moss, 2009 1. SAINTS ACCA AND ALCMUND, BISHOPS OF HEXHAM ......................5 2. SAINT ADRIAN, ABBOT OF CANTERBURY...............................................8 3. SAINT ADRIAN, HIEROMARTYR BISHOP OF MAY and those with him ....................................................................................................................................9 4. SAINT AIDAN, BISHOP OF LINDISFARNE...............................................11 5. SAINT ALBAN, PROTOMARTYR OF BRITAIN.........................................16 6. SAINT ALCMUND, MARTYR-KING OF NORTHUMBRIA ....................20 7. SAINT ALDHELM, BISHOP OF SHERBORNE...........................................21 8. SAINT ALFRED, MARTYR-PRINCE OF ENGLAND ................................27 9. SAINT ALPHEGE, HIEROMARTYR ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY ..................................................................................................................................30 10. SAINT ALPHEGE “THE BALD”, BISHOP OF WINCHESTER...............41 11. SAINT ASAPH, BISHOP OF ST. ASAPH’S ................................................42 12. SAINTS AUGUSTINE, LAURENCE, MELLITUS, JUSTUS, HONORIUS AND DEUSDEDIT, ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ..............................43 13. SAINTS BALDRED AND BALDRED, MONKS OF BASS ROCK ...........54 14. SAINT BATHILD, QUEEN OF FRANCE....................................................55 15. SAINT BEDE “THE VENERABLE” OF JARROW .....................................57 16. SAINT BENIGNUS (BEONNA) -

Salisbury Diocese (Including Dorset and Wiltshire)

Holidays with a religious connection Salisbury Diocese (including Dorset and Wiltshire) Shaftesbury Abbey was founded by Alfred the Great in 888 - he installed his daughter Aethelgifu as the first abbess. It was closed by Thomas Cromwell in 1539 as part of the Dissolution of the Monasteries and is now ruins. Alas the attraction was closed when we visited Shaftesbury on January 2nd, a bank holiday. Day 3 – Shaftesbury On the third day of our visit we travelled to Shaftesbury in Dorset. It’s a town steeped in history – the nunnery, Shaftesbury Abbey was founded by Alfred the Great in 888 and became of the wealthiest in England before its dissolution in 1539. On arrival we took a walk along Abbey Walk, the wonderful promenade that overlooks one of England’s most glorious landscapes. It’s great to have such a feature in the middle of the town. Abbey Walk, Shaftesbury; right - War Memorial in Abbey Walk. The famous Gold Hill, Shaftesbury. It was featured in the 1973 Hovis Bread advertisement, which featured a boy struggling to deliver a loaf to the top of the steep hill, then freewheeling back down again to Dvorak’s ‘New World’ Symphony No 9. It also appears in the 1967 film version of Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd. The film starred Julie Christie, Alan Bates, Terence Stamp and Peter Finch, and was directed by John Schlesinger. Shaftesbury was the ‘Shaston’ in Hardy’s novels. The Hovis ad is commemorated outside the Town Hall, at the top of Gold Hill - visitors can place a donation in the box for the upkeep of the cobbled surface of the hill. -

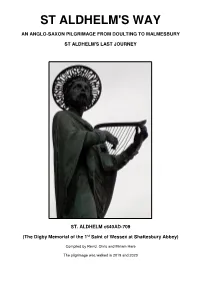

St Aldhelm's Way

ST ALDHELM'S WAY AN ANGLO-SAXON PILGRIMAGE FROM DOULTING TO MALMESBURY ST ALDHELM'S LAST JOURNEY ST. ALDHELM c640AD-709 (The Digby Memorial of the 1st Saint of Wessex at Shaftesbury Abbey) Compiled by Rev'd. Chris and Miriam Hare The pilgrimage was walked in 2019 and 2020 AN INTRODUCTION TO CHRISTIANITY AND TO THE ANGLO SAXONS Christianity was first practised in Britain towards the end of the second century, and was mostly based in towns where paganism was also practised. Germanic tribes started to settle in Romano-Celtic Britain in the middle of the fifth century. The Angles came from modern Denmark, the Saxons from modern northern Germany and the Jutes from the coast of Germany and Holland. Saxons conquered South West England in the sixth century and formed the kingdom of the West Saxns. They were pagans and Christianity had nearly died out. In 596AD Pope Gregory sent a mission led by Augustine to “ preach the word of God to the English race". They arrived in Thanet in Kent in 597AD. King Aethelberht of Kent's wife was already a Christian, and he was converted and then baptised. Soon after 10,000 converts were baptised on Christmas Day in 597AD, and many others followed. Old churches were restored and new ones were built. Roman Christianity had come to England. Then Pope Gregory’s successor, Honorius, sent another mission with Bishop Birinus to England in 634AD again to preach the gospel. He landed in Wessex, baptised the king of the West Saxons, Cynegils, and then many of the population of Wessex. -

Shroud News Issue #66 August 1991

A NEWSLETTER ABOUT THE HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN edited by REX MORGAN, Author of several books on the Shroud Issue Number 66 AUGUST 1991 Dr JEAN VOLCKRINGER OF PARIS WHO FIRST PRESENTED THE CELLULOSE DEGRADATION IMAGE FORMATION THEORY IN 1942 DIED ON 6 JUNE 1991 AGED 85 A FEW WEEKS AFTER HIS WORK WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN ENGLISH [Pic: Rex Morgan 1988] 2 SHROUD NEWS No 66 (August 1991) EDITORIAL Since the last issue of Shroud News I have had the privilege of giving an address at the prestigious St Louis, Missouri, Shroud Conference. This was one of the best organised conferences I have attended and the wide range of papers given by experts from several countries provided a great deal of new research information and an enormous exchange of ideas. The very fact that only about 100 delegates attended meant that everyone could talk to everyone else in those vital breaks, befores and afters and everything was brilliantly organised in one building with accommodation hard by. I am preparing a complete report of the conference and all its papers for our October issue. I was, unfortunately, the one able to announce the death of Dr Jean Volckringer to the conference, news of which I had received only the day before in Sydney. My memorial to him is in this issue. After the USA, where I met with numerous members of the Shroud circle, I was able to visit the south of England to pursue some Shroud researches and there I met again with Audrey Dymock Herdsman of Templecombe. This time I managed to persuade her to write her article The Templars' Journey to Somerset. -

'In Me Porto Crucem': a New Light on the Lost St Margaret's Crux Nigra

© The Author(s) 2020. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ‘In me porto crucem’: a new light on the lost St Margaret’s crux nigra Francesco Marzella Abstract St Margaret of Scotland owned a reliquary containing a relic of the True Cross known as crux nigra. Both Turgot, Margaret’s biographer, and Aelred of Rievaulx, who spent some years at the court of Margaret’s son, King David, mention the reliquary without offering sufficient information on its origin. The Black Rood was probably lost or destroyed in the sixteenth century. Some lines written on the margins of a twelfth- century manuscript containing Aelred’s Genealogia regum Anglorum can now shed a new light on this sacred object. The mysterious lines, originally written on the Black Rood or more probably on the casket in which it was contained, claim that the relic once belonged to an Anglo-Saxon king, and at the same time they seem to convey a signifi- cant political message. In his biography of St Margaret of Scotland,1 Turgot († 1115),2 at the time prior of Durham, mentioned an object that was particularly dear to the queen. It was a cross known as crux nigra. In chapter XIII of his Vita sanctae Margaretae, Turgot tells how the queen wanted to see it for the last time when she felt death was imminent: 3 Ipsa quoque illam, quam Nigram Crucem nominare, quamque in maxima semper ven- eratione habere consuevit, sibi afferri præcepit. -

The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society

The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society Founded 1946 Issue: April 2015 The Shaftesbury & District Historical Society Registered Charity No. 1156273 1 C O N T E N T S ( v i c e ) c h a i r m a n ’s C h a t Ian Kellett I have had to step into the breach as Terry is still recovering from an illness which recently saw him hospitalised for ten days. He has, however, penned a piece about his starring role in Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is, which we weren’t allowed to publicise prior to broadcast on 06 March. Faced with the unblinking eye of the camera, Terry represented the Society very effectively, and generously, and we hope that he and Anita will soon be back at the Museum. Also in March we welcomed Claire Ryley to the committee of Trustees. In some respects this means no change, because Claire has managed our very popular joint education programme with the Abbey for some years. But she is also about to take charge of an exciting Great War Project financed by a small grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. We can at last report this terrific news, and you can read our HLF-approved Press release elsewhere in this Newsletter. And still in March we were sad to say goodbye as a Trustee to Barbara Ambrose, who first stepped back for health reasons and then decided to step down. Barbara helped to raise funds for the Museum’s redevelopment, before taking on responsibility for managing our stewards’ rota and then public relations.