Women's Access to Justice in Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Inventory of Library by Categories Penny Kittle

2015 Inventory of Library by Categories Penny Kittle The World: Asia, India, Africa, The Middle East, South America & The Caribbean, Europe, Canada Asia & India Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West by Blaine Harden Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo Life of Pi by Yann Martel Boxers & Saints by Geneluen Yang American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry Jakarta Missing by Jane Kurtz The Buddah in the Attic by Julie Otsuka First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung A Step From Heaven by Anna Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai Slumdog Millionaire by Vikas Swarup The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri Unaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa Lahiri The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang Girl in Translation by Jean Kwok The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick Q & A by Vikas Swarup Never Fall Down by Patricia McCormick A Moment Comes by Jennifer Bradbury Wave by Sonali Deraniyagala White Tiger by Aravind Adiga Africa What is the What by Dave Eggers They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky by Deng, Deng & Ajak Memoirs of a Boy Soldier by Ishmael Beah Radiance of Tomorrow by Ishmael Beah Running the Rift by Naomi Benaron Say You’re One of Them by Uwem Akpan Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Journey of a Desert Nomad by Waris Dirie The Milk of Birds by Sylvia Whitman The -

Five Provinces (Jawzjan, Balkh, Baghlan, Kunduz and Badakhshan) of Afghanistan

ITB NO. 9152 For the Rehabilitation of justice facilities at 10 districts in 5 provinces (Jawzjan, Balkh, Baghlan, Kunduz and Badakhshan,) INVITATION TO BID FOR THE REHABILITATION OF JUSTICE FACILITES AT TEN DISTRICTS OF FIVE PROVINCES (JAWZJAN, BALKH, BAGHLAN, KUNDUZ AND BADAKHSHAN) OF AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY: ............................... ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF AFGHANISTAN PROJECT NAME:………………….. JUSTICE AND HUMAN RIGHTS IN AFGHANISTAN-DISTRICT LEVEL COMPONENT PROJECT NUMBER: ................................................................ 00071252 ISSUE DATE: 07 OCTOBER 2009 Section 1 – Instruction to Bidders Page 1 of 104 ITB NO. 9152 For the Rehabilitation of justice facilities at 10 districts in 5 provinces (Jawzjan, Balkh, Baghlan, Kunduz and Badakhshan,) PLEASE READ CAREFULLY CHECK LIST FOR COMPLETE BID SUBMISSION BID SUBMISSION FORM (SECTION 7, PAGE 100) OF THIS DOCUMENT); PROJECT LIST; This must describe at least five rehabilitation/construction projects valued at over $ 500,000.00 completed in the past five years and must also include the names and contact details (telephone numbers and email addresses) of clients; CLIENT REFERENCES (IF ANY) STAFF LIST; This must clearly identify the Senior Manager/Company Director, Senior Civil Engineer, Senior Design Engineer, Senior Site Engineer and two Junior Site Engineers. STAFF CURRICULUM VITAES; This must include CVs for the Senior Manager/Company Director, Senior Civil Engineer, Senior Design Engineer, Senior Site Engineer and two Junior Site Engineers. EQUIPMENT AND MACHINERY LIST -

3. (SINF) JTF GTMO Assessment

SECRET 20300527 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE JOINT TASK FORCE GUANTANAMO GUANTANAMO BAY, CUBA APO AE 09360 GTMO- CG 27 May 2005 MEMORANDUMFORCommander, United States Southern Command, 3511NW Avenue, Miami, FL 33172 SUBJECT: UpdateRecommendationto Retainin DoDControl( ) for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN: US9AF-001002DP(S) JTF GTMO DetaineeAssessment 1. (FOUO) Personal Information: JDIMS NDRC Reference Name: AbdulMateen Aliases and Current/ True Name: Qari AbdulMateen, Mullah Shahzada, Qari AbdulMatin Shahzada Mohommad Nabi, Abdul Matin Place of Birth: Tanka Village Jowzjan Province/ Afghanistan (AF) Date of Birth: January 1965 Citizenship: Afghanistan InternmentSerial Number (ISN) : US9AF-001002DP 2. (FOUO) Health Detainee is in good health. Detainee has no travel restrictions. 3. ( SI NF) JTF GTMO Assessment : a . (S ) Recommendation : JTF GTMO recommends this detainee be Retained in Control ( . b . ( SI/NF) Summary: JTF GTMO previously assessed detainee as Transfer to the Control of Another Country for Continued Detention ( TRCD ) on 29 March 2004. Based upon information obtained since detainee's previous assessment, it is now recommended he be Retained in DoD Control ( . CLASSIFIED BY: MULTIPLE SOURCES REASON: E.O. 12958 SECTION 1.5 (C ) DECLASSIFY ON : 20300527 SECRET//NOFORN 20300527 SECRETI // 20300527 JTF GTMO-CG SUBJECT: UpdateRecommendationto Retainin DoD Control( for Guantanamo Detainee, ISN: -001002DP(S) For this update recommendation, detainee is assessed as a member of the Taliban intelligence network . Detainee was an assistant to the Mazar - E -Sharif Taliban Intelligence Chief, Sharifuddin ( Sharafat). During a period when Sharifuddin (Sharafat) was ill, the detainee temporarily commanded the intelligence organization inMazar- E -Sharif, AF . During this period, detainee ordered the local population to disarm , and he is accused of having the Mayor of Mazar- E -Sharif, Alam Khan, assassinated. -

“The Golden Hill: Tillya Tepe”

The Heart of Asia Herald Volume 2 Issue 2 In This Issue Jun.-Sept. 2018 Feature Story “The Golden Hill: Tillya Tepe” Afghanistan’s hidden gold treasure, the Tillya Tepe (Golden Hill) was found in Sheberghan City, Jowzjan, but went missing for years before another sudden discovery of the artifacts in 1979...(p.3) Province Focus: Jowzjan………………..…2 Afghans You Should Know………………....5 Afghan-Japan Relations………………...….4 Afghan Recipes………………………………6 Security & Trade……………………………4 Upcoming Events…………………………....6 1 Province Focus Jowzjan owzjan province is one of most important locations in northern Afghanistan due to its Jowzjan province has immense gas re- J border with Turkmenistan. It has the total serves population of about 512,100 people, almost one- Sand, lime, gypsum, and natural gas are abundant in the region third of which resides in the capital city of She- There are 5 known areas with rich nat- berghan. ural gas reservoirs There are 8 gas wells in the outskirts of The area is also known to be abundant with gas and Jerqoduq, Yatim Taq, and the areas of natural resources yet remain untouched until today. Sheberghan City In order to safeguard these resources, the Afghan Each well produces 260,000 cubic me- ters of gas in a day Ministry of Mines have introduced strict measures 300 gas wells were certified by Russian to prevent illicit exploitation, one of them was the and Afghan experts in 1960. Afghanistan Hydrocarbons Law in 2007. 2 2 Feature Story Tillya Tepe: The Golden Hill Afghanistan’s Lost Treasure fghanistan’s hidden gold treasure, also known as The Bactrian Gold of the Tillya Tepe (Golden Hill), A was found in Sheberghan City, Jowzjan, by a Soviet- Afghan team led by the Greek-Russian archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi. -

Recruitment and Radicalization of School-Aged Youth by International

HOMELAND SECURITY INSTITUTE The Homeland Security Institute (HSI) is a federally funded research and development center (FFRDC) established by the Secretary of Homeland Security under Section 312 of the Homeland Security Act of 2002. Analytic Services Inc. operates HSI under contract number W81XWH-04-D-0011. HSI’smiiission istoassist the Secretary of HldHomeland SiSecurity, the UdUnder Secretary for Science and Technology, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) operating elements in addressing national policy and security issues where scientific, technical, and analytical expertise is required. HSI also consults with other government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, institutions of higher education, and nonprofit organizations. HSI delivers independent and objective analyses and advice to support policy developp,ment, decision making, alternative approaches, and new ideas on significant issues. HSI’s research is undertaken by mutual consent with DHS and is organized by Tasks in the annual HSI Research Plan. This report presents the results of research and analysis conducted under Task 08-37, Implications for U.S. Educators on the Prevalence and Tactics Used to Recruit Youth for Violent or Terrorist Activities Worldwide of HSI’s Fiscal Year 2008 Research Plan. The purpose of the task is to look at the phenomenon of school-aged individuals being recruited by individuals or groups that promote violence or terrorissm. The results presented in this report do not necessarily reflect official DHS opinion or policy. Homeland Security Institute Catherine Bott Task lead, Threats Analysis Division W. James Castan Robertson Dickens Thomas Rowley Erik Smith Rosemary Lark RECRUITMENT AND Fellow & Division Manager, Threats Analysis Division RADICALIZATION OF George Thompson, SCHOOL-AGED YOUTH Deputy Director, HSI BY INTERNATIONAL TERRORIST GROUPS Final Report 23 April 2009 Prepared for U.S. -

Security Council Distr.: General 30 May 2018

United Nations S/2018/466 Security Council Distr.: General 30 May 2018 Original: English Letter dated 16 May 2018 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith the ninth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team established pursuant to resolution 1526 (2004), which was submitted to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011), in accordance with paragraph (a) of the annex to resolution 2255 (2015). I should be grateful if the present letter and the report could be brought to the attention of the Security Council members and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Kairat Umarov Chair Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) 18-06956 (E) 050618 *1806956* S/2018/466 Letter dated 30 April 2018 from the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team addressed to the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) I have the honour to refer to paragraph (a) of the annex to Security Council resolution 2255 (2015), in which the Council requested the Monitoring Team to submit, in writing, two annual comprehensive, independent reports to the Committee, on implementation by Member States of the measures referred to in paragraph 1 of the resolution, including specific recommendations for improved implementation of the measures and possible new measures. I therefore transmit to you the ninth report of the Monitoring Team, pursuant to the above-mentioned request. The Monitoring Team notes that the original language of the report is English. -

Upholding Citizen Honor? Rape in the Courts and Beyond

6 Upholding Citizen Honor? Rape in the Courts and Beyond INTRODUCTION Given the strong legal and social regulation of women’s sexuality in Afghanistan, as well as how this issue has been tied up with social status and “honor,” it is un- surprising that there has historically been a great reluctance to report cases of rape.1 Women themselves would risk being ostracized by both family and society, and they could also be charged with zina or other moral crimes. To families, going to the authorities with a complaint of rape could signal weakness—an admission that the family was incapable of settling its own affairs. The successful regulation of female sexuality has been considered a key locus of family and kinship power, to be jealously guarded against outside involvement. Extramarital sexual relations have been highly shameful for a woman and her family, often irrespective of the consent of the woman. Not only would her status as a wife or prospective wife be ruined or significantly diminished, but the public knowledge of such a crime would also severely taint a family’s reputation—it would be seen as unable to pro- tect (or police) its women. Yet over period of a few years, Afghanistan witnessed a number of high-profile rape cases in which public mobilization for government intervention led to asser- tive state action. Around 2008, a number of families went on national television with demands that the government punish their daughters’ rapists. Harrowing television clips showed the young girls and their families wailing and weeping, crosscut with footage of male family members calling for justice. -

Security Report November 2010 - June 2011 (PART II)

Report Afghanistan: Security Report November 2010 - June 2011 (PART II) Report Afghanistan: Security Report November 2010 – June 2011 (PART II) LANDINFO – 20 SEPTEMBER 2011 1 The Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo) is an independent body that collects and analyses information on current human rights situations and issues in foreign countries. It provides the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), Norway’s Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police with the information they need to perform their functions. The reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from both public and non-public sources. The information is collected and analysed in accordance with source criticism standards. When, for whatever reason, a source does not wish to be named in a public report, the name is kept confidential. Landinfo’s reports are not intended to suggest what Norwegian immigration authorities should do in individual cases; nor do they express official Norwegian views on the issues and countries analysed in them. © Landinfo 2011 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. Box 8108 Dep NO-0032 Oslo Norway Tel: +47 23 30 94 70 Fax: +47 23 30 90 00 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.landinfo.no Report Afghanistan: Security Report November 2010 – June 2011 (PART II) LANDINFO – 20 SEPTEMBER 2011 2 SUMMARY The security situation in most parts of Afghanistan is deteriorating, with the exception of some of the big cities and parts of the central region. -

First Edition Dec 2009 I

First Edition Dec 2009 i Purpose To ensure that U.S. Army personnel have a relevant, comprehensive guide to use in capacity building and counterinsurgency operations while deployed in the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan ii TABLE OF CONTENTS History ....................................................................................................................... 1 Political ..................................................................................................................... 9 Flag of Afghanistan ............................................................................................ 11 Political Map ....................................................................................................... 12 Political Structure .............................................................................................. 13 Relevant Country Data .......................................................................................... 15 Location and Bordering Countries ................................................................... 16 Comparative Area .............................................................................................. 17 Social Statistics .................................................................................................. 18 Economy ............................................................................................................. 19 Land Use and Economic Activity ..................................................................... 20 Military Operational Environment -

Culture As an Obstacle to Universal Human Rights? the Encounter of the Royal Netherlands Army with the Afghan Culture in Uruzgan

Culture as an Obstacle to Universal Human Rights? The Encounter of the Royal Netherlands Army with the Afghan Culture in Uruzgan Name: Karen de Jong Student number: 4171985 Master thesis: International Relations in Historical Perspective Supervisor: dr. Frank Gerits 13.356 words Table of contents Abstract 3 Glossary of acronyms and terms 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1: The Status of Human Rights and Culture in the Path to Uruzgan 10 1.1 Universalization of Human Rights 10 1.2 Culture as an Obstacle to Human Rights 11 1.3 The Road to Uruzgan: Policy of the Ministry of Defense 14 1.4 Conclusion 19 Chapter 2: The Royal Netherlands Army in Pashtun Dominated Uruzgan during the War on Terror 20 2.1 War in Afghanistan 20 2.2 Dutch Boots on the Uruzgan Ground 22 2.3 The Encounter with the Local Population and the Afghan National Security Forces on an Operational Level 25 2.4 Conclusion 29 Chapter 3: A System of Gender Reversal in Afghanistan: Perceptions of Dutch Soldiers on Gender in Afghanistan 31 3.1 Women are for Children and Boys are for Pleasure 31 3.2 Afghanistan as one of the Worst Countries to Live in as a Woman 40 3.2 Conclusion 45 Conclusion 47 Bibliography 50 Appendix: Plagiarism statement 2 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to investigate how Dutch soldiers of the Royal Netherlands Army dealt with the distinctive Afghan culture during the mission in Uruzgan from 2006 to 2010. This thesis indicates the conflicting cultural values Dutch soldiers encountered when engaging with the local population and the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). -

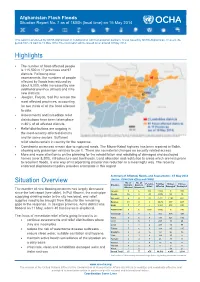

Highlights Situation Overview

Afghanistan Flash Floods Situation Report No. 7 as of 1800h (local time) on 15 May 2014 This report is produced by OCHA Afghanistan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It was issued by OCHA Afghanistan. It covers the period from 24 April to 15 May 2014. The next report will be issued on or around 20 May 2014. Highlights The number of flood-affected people is 115,500 in 17 provinces and 97 districts. Following new assessments, the numbers of people affected by floods has reduced by about 6,000, while increased by one additional province (Khost) and nine new districts. Jawzjan, Faryab, Sari Pul remain the most affected provinces, accounting for two thirds of all the flood affected to date. Assessments and immediate relief distributions have been taken place in 80% of all affected districts. Relief distributions are ongoing in the most-recently affected districts and for some sectors. Sufficient relief stocks remain in country for the response. Constraints on access remain due to ruptured roads. The Mazar-Kabul highway has been repaired in Balkh, allowing only passenger vehicles to use it. There are no material changes on security related access. More and more attention is on the planning for the rehabilitation and rebuilding of damaged and destroyed homes (over 8,300), infrastructure and livelihoods. Land allocation and restitution to areas which are less prone to recurrent floods, is one way of incorporating disaster risk reduction in a meaningful way. The recently endorsed displacement policy provides a template in this regard. Summary of Affected, Needs, and Assessments ‐ 15 May 2014 (Source: OCHA field offices and PDMC) Situation Overview No. -

Atia Abawi Der Geheime Himmel Atia Abawi, Als Kind Afghanischer Eltern in Deutschland Geboren, Wuchs in Den USA Auf

BB 1 71753 Atia Abawi Der geheime Himmel Atia Abawi, als Kind afghanischer Eltern in Deutschland geboren, wuchs in den USA auf. Bereits als Schülerin wusste sie, dass sie einmal Journalistin werden wollte. Sie berichtete u. a. fünf Jahre lang alsAuslandskorrespondentin für verschie- dene amerikanische Fernsehsender aus Kabul. Heute lebt sie mit ihrer Familie in Jerusalem. ›Der geheime Himmel‹ ist © Conor Powell ihr erster Roman und basiert auf ihren Erfahrungen, die sie in Afghanistan gemacht hat; er fand sofort breites Interesse in den Medien und wurde sehr positiv besprochen. www.atiaabawi.com Bettina Münch arbeitete nach dem Studium als Kinderbuchlektorin. Heute ist sie freie Autorin und Übersetzerin und lebt mit Mann und Tochter in der Nähe von Frankfurt am Main. Atai Abawi Der geheime Himmel Eine Geschichte aus Afghanistan Roman Aus dem amerikanischen Englisch von Bettina Münch Ausführliche Informationen über unsere Autoren und Bücher www.dtv.de Die Übersetzung des Werkes wurde von der Kunststiftung Nordrhein-Westfalen und dem Europäischen Übersetzerkollegium in Straelen gefördert. Ungekürzte Ausgabe 2017 dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH und Co. KG, München © 2014 Atia Abawi Titel der amerikanischen Originalausgabe: ›The Secret Sky. A Novel of Forbidden Love in Afghanistan‹, 2014 erschienen bei Philomel Books This edition published by arrangement with Philomel Books, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company. © für die deutschsprachige Ausgabe: 2015 dtv Verlagsgesellschaft mbH und Co. KG, München Umschlaggestaltung: Katharina Netolitzky unter Verwendung des artworks von Semadar Megged Gesetzt aus der Faireld LT Satz: Fotosatz Amann, Memmingen Druck und Bindung: Druckerei C.H.Beck, Nördlingen Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, chlorfrei gebleichtem Papier Printed in Germany ∙ ISBN 978-3-423-71753-3 Für die Menschen, die mich die Liebe – in all ihren Formen – gelehrt haben: meine Eltern Wahid und Mahnaz, meinen Bruder Tawab und meinen Mann Conor, den zu nden mir bestimmt war.