Case 1:11-Cv-24110-JJO Document 211 Entered on FLSD Docket 06/28/13 16:08:11 Page 1 of 34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trademark Law and the Prickly Ambivalence of Post-Parodies

8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE) 8/28/2014 3:07 PM ESSAY TRADEMARK LAW AND THE PRICKLY AMBIVALENCE OF POST-PARODIES CHARLES E. COLMAN† This Essay examines what I call “post-parodies” in apparel. This emerging genre of do-it-yourself fashion is characterized by the appropriation and modification of third-party trademarks—not for the sake of dismissively mocking or zealously glorifying luxury fashion, but rather to engage in more complex forms of expression. I examine the cultural circumstances and psychological factors giving rise to post-parodic fashion, and conclude that the sensibility causing its proliferation is grounded in ambivalence. Unfortunately, current doctrine governing trademark “parodies” cannot begin to make sense of post-parodic goods; among other shortcomings, that doctrine suffers from crude analytical tools and a cramped view of “worthy” expression. I argue that trademark law—at least, if it hopes to determine post-parodies’ lawfulness in a meaning ful way—is asking the wrong questions, and that existing “parody” doctrine should be supplanted by a more thoughtful and nuanced framework. † Acting Assistant Professor, New York University School of Law. I wish to thank New York University professors Barton Beebe, Michelle Branch, Nancy Deihl, and Bijal Shah, as well as Jake Hartman, Margaret Zhang, and the University of Pennsylvania Law Review Editorial Board for their assistance. This piece is dedicated to Anne Hollander (1930–2014), whose remarkable scholarship on dress should be required reading for just about everyone. (11) 8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE)8/28/2014 3:07 PM 12 University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online [Vol. -

![[Hot] 'Jersey Shore' Star Mike 'The Situation' Has Only Done 18 of His](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6972/hot-jersey-shore-star-mike-the-situation-has-only-done-18-of-his-476972.webp)

[Hot] 'Jersey Shore' Star Mike 'The Situation' Has Only Done 18 of His

TOP STORIES MENU 'Jersey Shore' star Mike 'The Situation' has only done 18 of his 500 community service hours: report NEW YORK DAILY NEWS | 3 MONTHS AGO | 1 MINUTE, 6 SECONDS READ Mike Sorrentino is facing a sticky situation. The "Jersey Shore" star known as The Situation has only finished 18 of the 500 community service hours he was ordered to do after he left prison in September 2019, TMZ reported. A probation officer wrote in court documents obtained by TMZ that she's urged Sorrentino "at nearly every interaction to find a venue for community service, including service that could be performed from home." Sorrentino, 38, served eight months at the Otisville Federal Correctional Institution in New York last year in a tax evasion case. This past August, he did not attend a previously scheduled volunteer outing out of concerns stemming from the coronavirus pandemic, the parole officer said. A judge has now given Sorrentino a written warning regarding his community service hours. Representatives for Sorrentino and the Otisville facility did not immediately respond to requests for comment. Sorrentino rose to fame as a cast member on MTV's "Jersey Shore" during the reality show's original run from 2009 to 2012. He has since returned in recent years for MTV's ongoing spinoff series, "Jersey Shore Family Vacation." The reality star and his wife, Lauren, recently announced they're expecting a first child. On Tuesday, Sorrentino said they have a baby boy on the way. "Gym Tan We're having a Baby Boy," he wrote in an Instagram post. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Internal Revenue Service - Criminal Investigation Chief Richard Weber Date: Dec. 16, 2015 Contact: *[email protected] IRS – Criminal Investigation CI Release #: CI-2015-12-16-A Accountant for Michael ‘The Situation’ Sorrentino Admits Tax Fraud Conspiracy The former tax preparer for television personality Michael “The Situation” Sorrentino and his brother, Marc Sorrentino, today admitted filing fraudulent tax returns on their behalf, Acting Assistant Attorney General Caroline D. Ciraolo of the Justice Department’s Tax Division and U.S. Attorney Paul J. Fishman of the District of New Jersey announced. Gregg Mark, 51, of Spotswood, New Jersey, pleaded guilty before U.S. District Judge Susan D. Wigenton in Newark federal court to an information charging him with one count of conspiracy to defraud the United States. According to documents filed in this case and statements made in court: Mark, formerly an accountant at a Staten Island, New York-based accounting firm, admitted preparing fraudulent tax returns for the Sorrentinos for tax years 2010 and 2011, during which time the Sorrentinos and their businesses – MPS Enterprises LLC and Situation Nation Inc. – received millions of dollars in income. To reduce the taxes the Sorrentinos owed, Mark caused to be prepared and filed with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) fraudulent business and personal tax returns. Mark admitted the Sorrentinos’ false returns defrauded the IRS out of $550,000 to $1.5 million. On Sept. 24, a grand jury in Newark returned a seven-count indictment charging the Sorrentinos with conspiracy to defraud the United States and filing false tax returns. -

Meeting Packet

Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting Date and Time Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM EDT Notice of this meeting was posted on the ANCS website and both ANCS campuses in accordance with O.C.G.A. § 50-14-1. Agenda Purpose Presenter Time I. Opening Items 6:30 PM Opening Items A. Record Attendance and Guests Kristi 1 m Malloy B. Call the Meeting to Order Lee Kynes 1 m C. Brain Smart Start Mark 5 m Sanders D. Public Comment 5 m E. Approve Minutes from Prior Board Meeting Approve Kristi 3 m Minutes Malloy Approve minutes for ANCS Governing Board Meeting on June 21, 2021 F. PTCA President Update Rachel 5 m Ezzo G. Principals' Open Forum Cathey 10 m Goodgame & Lara Zelski Standing monthly opportunity for ANCS principals to share highlights from each campus. II. Executive Director's Report 7:00 PM A. Executive Director Report FYI Chuck 20 m Meadows Powered by BoardOnTrack 1 of1 of393 2 Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School - ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting - Agenda - Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM Purpose Presenter Time III. DEAT Update 7:20 PM A. Monthly DEAT Report FYI Carla 5 m Wells IV. Finance & Operations 7:25 PM A. Monthly Finance & Operations Report Discuss Emily 5 m Ormsby B. Vote on 2021-2022 Financial Resolution Vote Emily 10 m Ormsby V. Governance 7:40 PM A. Monthly Governance Report FYI Rhonda 5 m Collins B. Vote on Committee Membership Vote Lee Kynes 5 m C. Vote on Nondiscrimination & Parental Leave Vote Rhonda 10 m Policies Collins D. -

California VOL

california VOL. 73 NO.Apparel 29 NewsJULY 10, 2017 $6.00 2018 Siloett Gets a WATERWEAR Made-for-TV Makeover TEXTILE Tori Praver Swims TRENDS In the Pink in New Direction Black & White Stay Gold Raj, Sports Illustrated Team Up TRENDS Cruise ’18— Designer STREET STYLE Viewpoint Venice Beach NEW RESOURCES Drupe Old Bull Lee Horizon Swim Z Supply 01.cover-working.indd 2 7/3/17 6:39 PM APPAREL NEWS_jan2017_SAF.indd 1 12/7/16 6:23 PM swimshowmiami.indd 1 12/27/16 2:41 PM SWIM COLLECTIVE BOOTH 528 MIAMI SHOW BOOTH 224 HALL B SURF EXPO BOOTH 3012 Sales Inquiries 1.800.463.7946 [email protected] • seaandherswim.com seaher.indd 1 6/28/17 2:30 PM thaikila.indd 4 6/23/17 11:56 AM thaikila.indd 5 6/23/17 11:57 AM JAVITS CENTER MANDALAY BAY NEW! - HALL 1B CONVENTION CENTER AUGUST SUN 06 MON 14 MON 07 TUES 15 TUES 08 WED 16 SPRING SUMMER 2018 www.eurovetamericas.com info@curvexpo | +1.212.993.8585 curve_resedign.indd 1 6/30/2017 9:39:24 AM curvexpo.indd 1 6/30/17 9:32 AM mbw.indd 1 7/6/17 2:24 PM miraclesuit.com magicsuitswim.com 212-730-9555 aandhswim.indd 6 6/28/17 2:13 PM creora® Fresh odor neutralizing spandex for fresh feeling. creora® highcloTM super chlorine resistant spandex for lasting fit and shape retention. Outdoor Retailer Show 26-29 July 2017 Booth #255-313 www.creora.com creora® is registered trade mark of the Hyosung Corporation for its brand of premium spandex. -

The Fashion Issue Why Fashion Pr Pros Are Taking More Creative Roles Online

Septmagazine:Layout 1 8/31/11 12:06 PM Page 1 THE FASHION ISSUE WHY FASHION PR PROS ARE TAKING MORE CREATIVE ROLES ONLINE PHILANTHROPY RULES THE ROOST AT BLOG CONFERENCE September 2011 | www.odwyerpr.com COMPANIES UNVEIL ‘TWEEN’ OUTREACH EFFORTS Septmagazine:Layout 1 8/31/11 12:06 PM Page 2 Leading Feature News Distribution Service MULTIMEDIA SUCCESS! COVER ALL YOUR MEDIA BASES PRINT,ONLINE,RADIO AND TV Also Included In the Lineup: • Posting on NAPSNET.COM • Search Engine Optimization • Twitter Feeds to Editors • Social Media • Blogging • Anchor Texting • Hyperlinking • RSS Feed in XML • Podcasting • YouTube CSNN Channel [email protected] • www.napsinfo.com New York Chicago Washington Los Angeles San Francisco 800-222-5551 312-856-9000 202-347-5000 310-552-8000 415-837-0500 Septmagazine:Layout 1 8/31/11 12:07 PM Page 3 Septmagazine:Layout 1 8/31/11 12:07 PM Page 4 Vol. 25, No. 9 September 2011 EDITORIAL PHILANTHROPY BEATS Social media inspires change, FREEBIES AT CONFERENCE depicts changing world. Corporate sponsors at popular blog 6 16 conferences are now taking the oppor- tunity to advertise their social respon- SUMMER’S EVE DELIVERS sibility wares. NOT-SO-FRESH MARKETING Summer’s Eve recently pulled a MEDIA LANDSCAPE PUTS PR series of television ads in response8 to PROS IN CREATIVE ROLES accusations they perpetuate stereotypes A dearth of editorial expertise at blogs about black and Latina women. 18 has put many creative decisions in the 16 hands of those crafting PR messages. CRISIS PLANS, CONFIDENCE LACKING AMONG EXECS. PROFILES OF BEAUTY According to a new study, security & FASHION PR FIRMS breach, fraud and investigation remain9 the 20 most common forms of company crisis. -

Hered White Frame for 5X7 Photo, 4X6 Slide 30

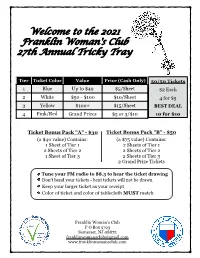

Welcome to the 2021 Franklin Woman's Club 27th Annual Tricky Tray Tier Ticket Color Value Price (Cash Only) 50/50 Tickets 1 Blue Up to $49 $5/Sheet $2 Each 2 White $50 - $100 $10/Sheet 4 for $5 3 Yellow $100+ $15/Sheet BEST DEAL 4 Pink/Red Grand Prizes $5 or 3/$10 10 for $10 Ticket Bonus Pack "A" - $30 Ticket Bonus Pack "B" - $50 (a $40 value) Contains: (a $75 value) Contains: 1 Sheet of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 2 2 Sheets of Tier 2 1 Sheet of Tier 3 2 Sheets of Tier 3 2 Grand Prize Tickets Tune your FM radio to 88.3 to hear the ticket drawing Don't bend your tickets - bent tickets will not be drawn Keep your larger ticket as your receipt Color of ticket and color of tablecloth MUST match Franklin Woman's Club P O Box 5793 Somerset, NJ 08875 [email protected] www.franklinwomansclub.com 11. Desk Set #1 Tier 1 Prizes 12. Desk Set #2 (Blue Tickets; Value up to $49) Black mesh letter sorter, pencil cup, clip holder and wastebasket 1. Cherry Blossom Spa Basket 13. Cake Pop Crush Japanese Cherry Blossom shower gel, bubble Cake Pops baking pan & accessories, cake pop bath, flower bath pouf, bath bombs, body and sticks, youth books “Cake Pop Crush” and hand lotion, more “Taking the Cake" 2. Friend Frame 14. Lunch Break "Friends" 6-opening photo collage picture frame FILA insulated lunch bag, pair of small snack for 2.25 X 3.25 inch photos containers 3. -

Fashion Content Standards Guide

Walmart Fashion Content Standards Updated Q4 2020 updated on: 11-17-20 Table of Contents Section 1: Content Section 4: Attribution Guidelines Importance of Content Men's & Women's Uniform & Workwear - Gowns & Coveralls 3 41 Attribute Definitions 82 Children's Apparel 42-45 How to Add Attributes 83 Section 2: Image Guidelines Gifting Sets Apparel 46-47 All Apparel Attributes 84-90 Image Requirements 5 All Tops, Items with Tops & Full Body Garments – Additional Attributes 91 Image Attributes 6 Section 3: Copy Guidelines All Tops with Collars, Robes, and Items with Collars – Additional Attributes 92 Silo Image Requirements - Photo Direction 7 Copy Standards 49 All Tops, Items with Tops, Intimates, Swimwear, & Dresses – Additional Attributes 93 Copy Definitions 50 Women's Dresses & Jumpsuits 8 All Jackets/Coats/Outerwear Tops & Sets with Jackets/Coats Additional Attributes 94 Search Engine Optimization 51 Women's Bodysuits & Outfit Sets 9 All Jackets/Coats/Outerwear & Weather Specific Bottoms –Additional Attributes 95 Writing Descriptions for Fashion 52 Women's Tops & Bottoms 10 All Athletic & Activewear - Additional Attributes 96 Women's Jackets & Coats 11 Legal Copy Information for All Categories 53 All Bottoms, Overalls/Coveralls, & Items with Bottoms - Additional Attributes 97 Women's Cloaks & Ponchos 12 All Upper Body Garments – Title Structures 54 All Pants, Overalls, & Items with Pants/Bottoms - Additional Attributes 98 Women’s Bundled/Multipacks – Tops 13 All Upper Body Garments - Copy Guidelines 55 All Shorts & Items with Shorts - -

Copycat-Walk:Parody in Fashion

78 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • January/February 2017 COPYCAT- PATRICK MCKEY, MARIA VATHIS, WALK: JANE KWAK, AND JOY ANDERSON PARODY IN FASHION LAW raditional legal commentaries and authorities caution against the potential dangers of parodies and the perceived negative effects they may have on trademark or copyright owners.1 Unsuccessful parodies constitute infringement. They also may constitute dilution, blurring, tarnishment, and unfairly confuse consumers and the public that the infringing Tproduct or item is made or endorsed by the aggrieved mark holder. Most designers and labels vigorously contest parodies, issuing cease-and-desist letters and, often, eventually filing suit. While these are necessary steps to protect one’s brand, goodwill, and the value of the mark, mark holders are increasingly considering whether parodies may actually benefit them in the long run. As the infamous sayings go: “All publicity is good publicity” and “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” Surprisingly, the fashion industry may be warming up to the idea, as parodies may even boost sales for the mark holder, while creating a whole new market for parody brands. Taking a glance at the two raincoats on the following page, it is wished Vetememes the best. He told The New York Times that “Ve- easy to initially mistake them for the same brand. Only a closer look tements will not be filing any lawsuits over the Vetememes raincoat (or a trained eye) reveals that jacket on the left is “VETEMENTS,” and hope[s] that [Tran] has enjoyed making his project as much as the cult Parisian brand launched in 2014 by Demma Gvasalia (for- we do making our clothes.”4 merly with Balenciaga) that’s making fashion headlines for its radical This article begins with an overview of trademark and copy- designs,2 and the one on the right is “VETEMEMES,” the Brook- right law, exploring both federal statutory regimes and various lyn-based parody brand started by Davil Tran. -

Advertising, Women, and Censorship

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 5 June 1993 Advertising, Women, and Censorship Karen S. Beck Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Karen S. Beck, Advertising, Women, and Censorship, 11(1) LAW & INEQ. 209 (1993). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol11/iss1/5 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Advertising, Women, and Censorship Karen S. Beck* I. Introduction Recently, a friend told me about a television commercial that so angers her that she must leave the room whenever it airs. The commercial is for young men's clothing and features female mod- els wearing the clothes - several sizes too large - and laughing as the clothes fall off, leaving the women clad in their underwear. A male voice-over assures male viewers (and buyers) that the cloth- ing company is giving them what they want. While waiting in line, I overhear one woman tell another that she is offended by the fact that women often appear unclothed in movies and advertisements, while men rarely do. During a discussion about this paper, a close friend reports that she was surprised and saddened to visit her childhood home and find some New Year's resolutions she had made during her grade school years. As the years went by, the first item on each list never varied: "Lose 10 pounds . Lose weight . Lose 5 pounds ...... These stories and countless others form pieces of a larger mo- saic - one that shows how women are harmed and degraded by advertising images and other media messages. -

Supplemental Materials for “Firm Participation in Voluntary Regulatory Initiatives”

Supplemental Materials for “Firm Participation in Voluntary Regulatory Initiatives” Import Genius search terms Apparel Jumper Silk Bathing short Jumpsuit Sleepwear Bathing suit Knit Sleeved Baby cloth* Leisurewear Sportswear Bedspread Lingerie Sock Bikini Loungewear Stocking Blazer Man-made fib* Sunsuit Blouse Manmade fib* Sweater Bodyshaper Mitten Sweatshirt Bra Neckwear Swimsuit Breeches Nightwear Swimwear Briefs Outerwear Suit Cardigan Pajama T-shirt Clothing Pants T shirt Clothe* Pantyhose Textile Coat Pillowcase Ties Cotton Sheet PJ Towel Culotte Playsuit Tracksuit Denim Polo Trouser Dress Pullover Underwear Duvet Pyjama Uniform Fabric Quilt Workwear Glove Robe Woven Handkerchief Sheets Yarns Hosiery Shirt Jacket Shorts Jean* Skort 1 Shipping volumes Figure 1 displays the volume of shipments from Bangladesh. For the purposes of comparison, Import Genius also provided summary data on total shipments arriving to the USA from anywhere in the world other than Bangladesh, satisfying the same set of search terms for the same time windows. We refer to these data as “rest of world” (RoW). Data in the figure is aggregated to the monthly level, in terms of kilograms, kilograms from Bangladesh as a percent of RoW weight, and number of shipments. A first glance suggests no noticeable decline in shipments around the April 2013 Rana Plaza event. Figure 1: US RMG imports from Bangladesh, 2011-15 USA monthly apparel import shipments from Bangladesh Weight Relative to RoW 5 ● 20 ● ● ●● ● ● ● ● ● ● 4 ● ●● ● ● ● 15 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 3 Rana Plaza ● ● ● ● ● 10 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● percent 2 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Kg (millions) ● ● ● ● 5 ●● ● ● 1 ● ● ● Rana Plaza ● ● ● ● ● ● ●● 0 0 ●● 2012 2013 2014 2015 2012 2013 2014 2015 Shipments ●● 3500 ● ● ● ● 3000 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 2500 ● ● ● ● ● ●● ● ● ● ● 2000 ● ● ● ● ● 1500 ● ● ● ● 1000 ● number of shipments number 500 0 Rana Plaza 2012 2013 2014 2015 The dates in our bills-of-lading represent the date of arrival, not the date of order or shipment. -

C:\Users\Jchamber\Appdata\Local

Case 2:15-cv-07980-DDP-JPR Document 31 Filed 12/15/15 Page 1 of 14 Page ID #:229 1 2 3 O 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 11 DC COMICS, ) Case No. CV 15-07980 DDP (JPRx) ) 12 Plaintiff, ) ORDER DENYING MOTION TO DISMISS ) 13 v. ) [Dkt. No. 25] ) 14 MAD ENGINE, INC., ) ) 15 Defendant. ) ___________________________ ) 16 17 Presently before the Court is Defendant Mad Engine’s Motion to 18 Dismiss. (Dkt. No. 25.) After considering the parties’ 19 submissions and hearing oral argument, the Court adopts the 20 following Order. 21 I. BACKGROUND 22 Plaintiff DC Comics is a publisher of comic books and owner of 23 related intellectual property. (Compl. ¶¶ 1, 9.) In this case, 24 Plaintiff is asserting its trademark rights in its Superman 25 character — specifically, the iconic shield design that Superman 26 wears on his chest. (Id. ¶ 10-14.) As provided by Plaintiff’s 27 complaint, “one well-known iteration of the design” is: 28 Case 2:15-cv-07980-DDP-JPR Document 31 Filed 12/15/15 Page 2 of 14 Page ID #:230 1 As the complaint provides, “[o]ne of the indicia most strongly 2 associated with Superman is the red and yellow five-sided shield 3 that appears on Superman’s chest.” (Id. ¶ 10.) Plaintiff has 4 registered a trademark in this shield design for adults’ and 5 children’s clothing, including t-shirts. (Id. Ex. 1 (U.S. 6 Trademark No. 1,184,881).) Plaintiff has also licensed this mark 7 on t-shirts, with the complaint providing examples: 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 As shown above, some of the licensed products are more humorous and 16 some are more traditional.