Jeans: a Comparison of Perceptions of Meaning in Korea and the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

She Has Good Jeans: a History of Denim As Womenswear

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 She Has Good Jeans: A History of Denim as Womenswear Marisa S. Bach Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the Fashion Design Commons, and the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Bach, Marisa S., "She Has Good Jeans: A History of Denim as Womenswear" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 317. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/317 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. She Has Good Jeans: A History of Denim as Womenswear Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Arts of Bard College by Marisa Bach Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Acknowledgements To my parents, for always encouraging my curiosity. To my advisor Julia Rosenbaum, for guiding me through this process. You have helped me to become a better reader and writer. Finally, I would like to thank Leandra Medine for being a constant source of inspiration in both writing and personal style. -

Trademark Law and the Prickly Ambivalence of Post-Parodies

8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE) 8/28/2014 3:07 PM ESSAY TRADEMARK LAW AND THE PRICKLY AMBIVALENCE OF POST-PARODIES CHARLES E. COLMAN† This Essay examines what I call “post-parodies” in apparel. This emerging genre of do-it-yourself fashion is characterized by the appropriation and modification of third-party trademarks—not for the sake of dismissively mocking or zealously glorifying luxury fashion, but rather to engage in more complex forms of expression. I examine the cultural circumstances and psychological factors giving rise to post-parodic fashion, and conclude that the sensibility causing its proliferation is grounded in ambivalence. Unfortunately, current doctrine governing trademark “parodies” cannot begin to make sense of post-parodic goods; among other shortcomings, that doctrine suffers from crude analytical tools and a cramped view of “worthy” expression. I argue that trademark law—at least, if it hopes to determine post-parodies’ lawfulness in a meaning ful way—is asking the wrong questions, and that existing “parody” doctrine should be supplanted by a more thoughtful and nuanced framework. † Acting Assistant Professor, New York University School of Law. I wish to thank New York University professors Barton Beebe, Michelle Branch, Nancy Deihl, and Bijal Shah, as well as Jake Hartman, Margaret Zhang, and the University of Pennsylvania Law Review Editorial Board for their assistance. This piece is dedicated to Anne Hollander (1930–2014), whose remarkable scholarship on dress should be required reading for just about everyone. (11) 8 Colman Final.docx (DO NOT DELETE)8/28/2014 3:07 PM 12 University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online [Vol. -

& What to Wear

& what to wear One of the most difficult areas of cruising can be what to pack; does the cruise have formal nights, casual night, and what should you wear? There are so many options, and so many cruise liners to & what to wear suit any fashionista!So here’s a guide to help you out. Not Permitted in Cruise Line On-board Dress Code Formal Nights Non Formal Nights Day Wear Restaurants • Polo Shirts • Trousers • No Bare Feet • Dinner Jacket • Casual • Tank Tops • Shirt • Swimwear • Swim Wear • Resort Casual N/A Azamara • Sports Wear • Caps • Casual Dresses • Jeans • Shorts • Separates • Jeans • Trousers • Suits • Jeans • Shorts • Tuxedos • Long Shorts • Swimwear • Beach Flip Flops • Cruise Casual • Dinner Jacket • Polo Shirts • Shorts • Swimwear • Cruise Elegant Carnival • T-Shirts • Cut-off Jeans • Evening Gown • Casual Dress • Summer Dresses • Sleeveless Tops • Dress • Trousers • Caps • Formal Separates • Blouses • Polo Shirt • Swimwear • T-Shirts • Trousers • Shorts • Swimwear • Tuxedo • Dinner jacket • Trousers • Robes • Formal • Suit (with Tie) • Dresses • T-Shirts • Tank Tops Celebrity • Smart Casual • Skirt • Jeans • Beachwear • Evening Gown • Blouse • Casual • Shorts • Trousers • Flip Flops • Jeans • Polo Shirts • Shirts • Swimwear • Suits • Shorts • Shorts Costa • Resort Wear • Summer dresses • Jeans • Swimwear • Cocktail Dresses • Casual separates • Sports Wear • Flip Flops • Skirts • T-shirts • Dinner Jacket • Suit ( no tie ) • Sensible shoes • Suit • Shorts • Formal • Warm jacket Cruise & Maritime • Casual dress • Swimwear • Deck -

Meeting Packet

Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting Date and Time Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM EDT Notice of this meeting was posted on the ANCS website and both ANCS campuses in accordance with O.C.G.A. § 50-14-1. Agenda Purpose Presenter Time I. Opening Items 6:30 PM Opening Items A. Record Attendance and Guests Kristi 1 m Malloy B. Call the Meeting to Order Lee Kynes 1 m C. Brain Smart Start Mark 5 m Sanders D. Public Comment 5 m E. Approve Minutes from Prior Board Meeting Approve Kristi 3 m Minutes Malloy Approve minutes for ANCS Governing Board Meeting on June 21, 2021 F. PTCA President Update Rachel 5 m Ezzo G. Principals' Open Forum Cathey 10 m Goodgame & Lara Zelski Standing monthly opportunity for ANCS principals to share highlights from each campus. II. Executive Director's Report 7:00 PM A. Executive Director Report FYI Chuck 20 m Meadows Powered by BoardOnTrack 1 of1 of393 2 Atlanta Neighborhood Charter School - ANCS Governing Board Monthly Meeting - Agenda - Thursday August 19, 2021 at 6:30 PM Purpose Presenter Time III. DEAT Update 7:20 PM A. Monthly DEAT Report FYI Carla 5 m Wells IV. Finance & Operations 7:25 PM A. Monthly Finance & Operations Report Discuss Emily 5 m Ormsby B. Vote on 2021-2022 Financial Resolution Vote Emily 10 m Ormsby V. Governance 7:40 PM A. Monthly Governance Report FYI Rhonda 5 m Collins B. Vote on Committee Membership Vote Lee Kynes 5 m C. Vote on Nondiscrimination & Parental Leave Vote Rhonda 10 m Policies Collins D. -

California VOL

california VOL. 73 NO.Apparel 29 NewsJULY 10, 2017 $6.00 2018 Siloett Gets a WATERWEAR Made-for-TV Makeover TEXTILE Tori Praver Swims TRENDS In the Pink in New Direction Black & White Stay Gold Raj, Sports Illustrated Team Up TRENDS Cruise ’18— Designer STREET STYLE Viewpoint Venice Beach NEW RESOURCES Drupe Old Bull Lee Horizon Swim Z Supply 01.cover-working.indd 2 7/3/17 6:39 PM APPAREL NEWS_jan2017_SAF.indd 1 12/7/16 6:23 PM swimshowmiami.indd 1 12/27/16 2:41 PM SWIM COLLECTIVE BOOTH 528 MIAMI SHOW BOOTH 224 HALL B SURF EXPO BOOTH 3012 Sales Inquiries 1.800.463.7946 [email protected] • seaandherswim.com seaher.indd 1 6/28/17 2:30 PM thaikila.indd 4 6/23/17 11:56 AM thaikila.indd 5 6/23/17 11:57 AM JAVITS CENTER MANDALAY BAY NEW! - HALL 1B CONVENTION CENTER AUGUST SUN 06 MON 14 MON 07 TUES 15 TUES 08 WED 16 SPRING SUMMER 2018 www.eurovetamericas.com info@curvexpo | +1.212.993.8585 curve_resedign.indd 1 6/30/2017 9:39:24 AM curvexpo.indd 1 6/30/17 9:32 AM mbw.indd 1 7/6/17 2:24 PM miraclesuit.com magicsuitswim.com 212-730-9555 aandhswim.indd 6 6/28/17 2:13 PM creora® Fresh odor neutralizing spandex for fresh feeling. creora® highcloTM super chlorine resistant spandex for lasting fit and shape retention. Outdoor Retailer Show 26-29 July 2017 Booth #255-313 www.creora.com creora® is registered trade mark of the Hyosung Corporation for its brand of premium spandex. -

Denim – Construction and Common Terminology

Denim – Construction and Common Terminology Denim Construction Denim is made from rugged tightly woven twill, in which the weft passes under two or more warp threads. Lengthwise, yarns are dyed with indigo or blue dye; horizontal yarns remain white. The yarns have a very strong twist to make them more durable, but this also affects the denim’s color. The yarns are twisted so tightly that the indigo dye usually colors only the surface, leaving the yarns center white. The blue strands become the threads that show on the outside of your denim, and the white are the ones that make the inside of your denim look white. This produces the familiar diagonal ribbing identifiable on the reverse of the fabric. Through wear, the indigo yarn surface gives way, exposing the white yarn underneath which causes denim to fade. Jeans are basic 5 pockets pants, or trousers, made from denim. The word comes from the name of a sturdy fabric called serge, originally made in Nimes, France. Originally called serge de Nimes (fabric of Nimes), the name was soon shortened to denim (de Nimes). Denim was traditionally colored blue with natural indigo dye to Black denim make blue Jeans, though “jean” then denoted a different, lighter cotton textile; the contemporary use of jean comes from the French word for Genoa, Italy, where the first denim trousers were made. Jeans transcend age, economic and style barriers. Washes, embellishments, leg openings and labels fluctuate with fashion whims, but jeans themselves have reached iconic status. Cross hatch denim Common terminology used in Denim fabric construction and processing ANTI-TWIST is a step in the finishing process, before sanforization, that corrects denim’s natural tendency to twist in the direction of the diagonal twill weaves. -

Addie Pietrowski - 8Th Grade Mackinaw Student - Tells About Her New Normal

by Sandy Planisek Mackinaw News MI Safe Start - Governor to Restart Economy by Region and Workplaces The governor has a plan to slowly allow business to reopen based on the region of the state and the type of business. The governor extended her emergency declaration for 28 days. She announced that residential and commercial construction crews can return to work on May 7th. Also, real estate activities and outdoor work can resume as well as workers who fulfill orders for curb-side pick-up from non-necessary stores, to care for a family member or pet in another household, visit people in health-care facilities, attend a funeral with 10 or less people, attend addiction meetings, and view real estate by appointment. Prohibited is travel to vacation rentals. Read the details at https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/MIEOG/2020/05/01/file_attachments/1441315/EO%202020-70.pdf May 3, 2020 page 1 Mackinaw News by Sandy Planisek No Prom - Help Celebrate With a Parade ! For Mackinaw’s Graduating Class Decorate your car and join a celebratory parade for Mackinaw’s graduating seniors on May 9th. Decorate your car, then proceed to the school parking lot at 7:45 pm for the line up. Parade begins at 8:30 pm. If you would rather stay home and are on the parade route, put out decorations or at least wave at the parade passes. Give these students the launch into their future that they deserve. Ron Dye May 3, 2020 page 2 Mackinaw News by Sandy Planisek MACKINAW CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PRESCHOOL OPEN HOUSE AND REGISTRATION INFO The preschool open house has been canceled due to COVID-19 restrictions. -

An Investigation of the Ergonomics of Jeans

(REFEREED RESEARCH) AN INVESTIGATION OF THE ERGONOMICS OF JEANS KOT PANTOLONUN ERGONOMİSİNİN İNCELENMESİ Esen ÇORUH Gazi University Vocational Education Faculty Departmant of Clothing Industry and Fashion Desigining Education e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this study was to investigate the ergonomics of jeans. In the study, a questionnaire was prepared in order to investigate the ergonomics of jeans, and to discover what problems subjects had while using them, and using the results, to propose design changes to the ergonomics of jean patterns. The questionnaire was conducted on 1170 university students, of whom 614 were female and 556 were male, whose heights ranged from 160cm and below to 181cm and over, whose weights ranged from 50kg and below to 76kg and over, of whom 430 preferred low waist jeans, 705 chose normal waist jeans, and 35 preferred high waist jeans. In addition to collecting this data, the questionnaire focussed on four factors: “the discomforts of tightness” (Factor 1), “the discomforts of stepping up stairs” (Factor 2), “the discomforts of strain” (Factor 3), and “the discomforts of opening waist on the back” (Factor 4). In the factor analysis, the following results were observed that women, 170cm and below, 60kg and below, and the participants preferring low waist jeans experienced the discomfort of opening waist on the back (Factor 4), 66-70kg, 76kg and over experienced the discomfort of tightness (Factor 1), and the participants preferring high waist jeans experienced the discomforts of tightness (Factor 1), stepping up stairs (Factor 2), and strains (Factor 3). These results clearly showed that there exists a real problem in the waist area of most jeans. -

Hered White Frame for 5X7 Photo, 4X6 Slide 30

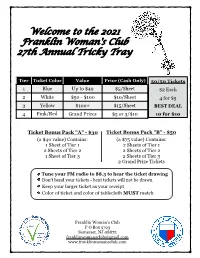

Welcome to the 2021 Franklin Woman's Club 27th Annual Tricky Tray Tier Ticket Color Value Price (Cash Only) 50/50 Tickets 1 Blue Up to $49 $5/Sheet $2 Each 2 White $50 - $100 $10/Sheet 4 for $5 3 Yellow $100+ $15/Sheet BEST DEAL 4 Pink/Red Grand Prizes $5 or 3/$10 10 for $10 Ticket Bonus Pack "A" - $30 Ticket Bonus Pack "B" - $50 (a $40 value) Contains: (a $75 value) Contains: 1 Sheet of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 1 2 Sheets of Tier 2 2 Sheets of Tier 2 1 Sheet of Tier 3 2 Sheets of Tier 3 2 Grand Prize Tickets Tune your FM radio to 88.3 to hear the ticket drawing Don't bend your tickets - bent tickets will not be drawn Keep your larger ticket as your receipt Color of ticket and color of tablecloth MUST match Franklin Woman's Club P O Box 5793 Somerset, NJ 08875 [email protected] www.franklinwomansclub.com 11. Desk Set #1 Tier 1 Prizes 12. Desk Set #2 (Blue Tickets; Value up to $49) Black mesh letter sorter, pencil cup, clip holder and wastebasket 1. Cherry Blossom Spa Basket 13. Cake Pop Crush Japanese Cherry Blossom shower gel, bubble Cake Pops baking pan & accessories, cake pop bath, flower bath pouf, bath bombs, body and sticks, youth books “Cake Pop Crush” and hand lotion, more “Taking the Cake" 2. Friend Frame 14. Lunch Break "Friends" 6-opening photo collage picture frame FILA insulated lunch bag, pair of small snack for 2.25 X 3.25 inch photos containers 3. -

Fashion Content Standards Guide

Walmart Fashion Content Standards Updated Q4 2020 updated on: 11-17-20 Table of Contents Section 1: Content Section 4: Attribution Guidelines Importance of Content Men's & Women's Uniform & Workwear - Gowns & Coveralls 3 41 Attribute Definitions 82 Children's Apparel 42-45 How to Add Attributes 83 Section 2: Image Guidelines Gifting Sets Apparel 46-47 All Apparel Attributes 84-90 Image Requirements 5 All Tops, Items with Tops & Full Body Garments – Additional Attributes 91 Image Attributes 6 Section 3: Copy Guidelines All Tops with Collars, Robes, and Items with Collars – Additional Attributes 92 Silo Image Requirements - Photo Direction 7 Copy Standards 49 All Tops, Items with Tops, Intimates, Swimwear, & Dresses – Additional Attributes 93 Copy Definitions 50 Women's Dresses & Jumpsuits 8 All Jackets/Coats/Outerwear Tops & Sets with Jackets/Coats Additional Attributes 94 Search Engine Optimization 51 Women's Bodysuits & Outfit Sets 9 All Jackets/Coats/Outerwear & Weather Specific Bottoms –Additional Attributes 95 Writing Descriptions for Fashion 52 Women's Tops & Bottoms 10 All Athletic & Activewear - Additional Attributes 96 Women's Jackets & Coats 11 Legal Copy Information for All Categories 53 All Bottoms, Overalls/Coveralls, & Items with Bottoms - Additional Attributes 97 Women's Cloaks & Ponchos 12 All Upper Body Garments – Title Structures 54 All Pants, Overalls, & Items with Pants/Bottoms - Additional Attributes 98 Women’s Bundled/Multipacks – Tops 13 All Upper Body Garments - Copy Guidelines 55 All Shorts & Items with Shorts - -

Copycat-Walk:Parody in Fashion

78 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • January/February 2017 COPYCAT- PATRICK MCKEY, MARIA VATHIS, WALK: JANE KWAK, AND JOY ANDERSON PARODY IN FASHION LAW raditional legal commentaries and authorities caution against the potential dangers of parodies and the perceived negative effects they may have on trademark or copyright owners.1 Unsuccessful parodies constitute infringement. They also may constitute dilution, blurring, tarnishment, and unfairly confuse consumers and the public that the infringing Tproduct or item is made or endorsed by the aggrieved mark holder. Most designers and labels vigorously contest parodies, issuing cease-and-desist letters and, often, eventually filing suit. While these are necessary steps to protect one’s brand, goodwill, and the value of the mark, mark holders are increasingly considering whether parodies may actually benefit them in the long run. As the infamous sayings go: “All publicity is good publicity” and “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.” Surprisingly, the fashion industry may be warming up to the idea, as parodies may even boost sales for the mark holder, while creating a whole new market for parody brands. Taking a glance at the two raincoats on the following page, it is wished Vetememes the best. He told The New York Times that “Ve- easy to initially mistake them for the same brand. Only a closer look tements will not be filing any lawsuits over the Vetememes raincoat (or a trained eye) reveals that jacket on the left is “VETEMENTS,” and hope[s] that [Tran] has enjoyed making his project as much as the cult Parisian brand launched in 2014 by Demma Gvasalia (for- we do making our clothes.”4 merly with Balenciaga) that’s making fashion headlines for its radical This article begins with an overview of trademark and copy- designs,2 and the one on the right is “VETEMEMES,” the Brook- right law, exploring both federal statutory regimes and various lyn-based parody brand started by Davil Tran.