Judicial Impunity for Disappearances in Punjab, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Demons Within"

Demons Within the systematic practice of torture by inDian police a report by organization for minorities of inDia NOVEMBER 2011 Demons within: The Systematic Practice of Torture by Indian Police a report by Organization for Minorities of India researched and written by Bhajan Singh Bhinder & Patrick J. Nevers www.ofmi.org Published 2011 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Organization for Minorities of India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the internet or a web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to: Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc PO Box 392 Lathrop, CA 95330 United States of America www.sovstar.com ISBN 978-0-9814992-6-0; 0-9814992-6-0 Contents ~ Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity 1 1. Why Indian Citizens Fear the Police 5 2. 1975-2010: Origins of Police Torture 13 3. Methodology of Police Torture 19 4. For Fun and Profit: Torturing Known Innocents 29 Conclusion: Delhi Incentivizes Atrocities 37 Rank Structure of Indian Police 43 Map of Custodial Deaths by State, 2008-2011 45 Glossary 47 Citations 51 Organization for Minorities of India • 1 Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity Impunity for police On October 20, 2011, in a statement celebrating the Hindu festival of Diwali, the Vatican pled for Indians from Hindu and Christian communities to work together in promoting religious freedom. -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF)

Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB MUNICIPAL SERVICES IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PMSIP) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Draft April 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: Punjab Municipal Infrastructure Development Company, Department of Local Government, Government of Punjab Public Disclosure Authorized i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE ESMF .................................................................................................................................. 13 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................... 15 2.1 PROJECT COMPONENTS .................................................................................................................................... 15 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS AND IMPACTS................................................................................................................ -

2020 03 19 O M.Pdf

file:///C:/Users/Admin/Desktop/HTML/2020_03_19_o_m.htm N O T E --------------------- The below mentioned cases will be listed in the Old Cases Cause list as per the dates so mentioned:- Sr. No. Case Details Party Details Advocate Name Listing Date 1. RSA-582-1989 (O&M) STATE OF PUNJAB AG PUNJAB, G.S DHILLON 19-MARCH-2020 V/S DASHMESH TRUCK BODY BUILDERS 2. RSA-1356-1989 (O&M) M/S RELIABLE AGRO K.K.MEHTA, O.P.HOSHIARPURI 19-MARCH-2020 ENGG. SERVICE PVT. LTD. V/S TARSEM SINGH 3. RSA-1600-1989 KEHAR SINGH V/S RAM ARUN JAIN,S S KAMBOJ,AVNISH 19-MARCH-2020 LUBHAYA MITTAL, DEEPAK ARORA,RAMAN WALIA, MAHESH GROVER 4. RSA-2334-1989 (O&M) KIRPAL KAUR V/S O.P.HOSHIARPURI, SARWAN SINGH 19-MARCH-2020 GURDIAL SINGH ETC. VIKAS WALIA, R.A. SHEORAN, , KARMINDER SINGH, RAJPAL, Y.K.SHARMA, , N S RAPRI 5. RSA-2440-1989 (O&M) BALWANT SINGH HEMANT KUMAR, A.K. AHLUWALIA 19-MARCH-2020 ETC. V/S DARSHOO @ K.L.MALHOTRA, VIPIN MAHAJAN, DARSHAN SINGH AMIT GUPTA. 6. RSA-904-1990 VINOD KUMAR AND OTHERS L.N. VERMA, S.P.LALLER, 19-MARCH-2020 V/S RAM PIARI AND B.S.CHAHAR, ASHOK VERMA, OTHERS 7. RSA-1060-1990 MUNSHI AND OTHERS JAI BHAGWAN TACORIA 19-MARCH-2020 V/S RAM SINGH B.R. MAHAJAN, K.S. KUNDU, RAJDEEP SINGH TACORIA ALL CONCERNED TO PLEASE NOTE. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- N O T E ----------------------- It is for the information of the all the Advocates/litigants that w.e.f.26.02.2020,in compliance of directions issued in RSA NO. -

State Profiles of Punjab

State Profile Ground Water Scenario of Punjab Area (Sq.km) 50,362 Rainfall (mm) 780 Total Districts / Blocks 22 Districts Hydrogeology The Punjab State is mainly underlain by Quaternary alluvium of considerable thickness, which abuts against the rocks of Siwalik system towards North-East. The alluvial deposits in general act as a single ground water body except locally as buried channels. Sufficient thickness of saturated permeable granular horizons occurs in the flood plains of rivers which are capable of sustaining heavy duty tubewells. Dynamic Ground Water Resources (2011) Annual Replenishable Ground water Resource 22.53 BCM Net Annual Ground Water Availability 20.32 BCM Annual Ground Water Draft 34.88 BCM Stage of Ground Water Development 172 % Ground Water Development & Management Over Exploited 110 Blocks Critical 4 Blocks Semi- critical 2 Blocks Artificial Recharge to Ground Water (AR) . Area identified for AR: 43340 sq km . Volume of water to be harnessed: 1201 MCM . Volume of water to be harnessed through RTRWH:187 MCM . Feasible AR structures: Recharge shaft – 79839 Check Dams - 85 RTRWH (H) – 300000 RTRWH (G& I) - 75000 Ground Water Quality Problems Contaminants Districts affected (in part) Salinity (EC > 3000µS/cm at 250C) Bhatinda, Ferozepur, Faridkot, Muktsar, Mansa Fluoride (>1.5mg/l) Bathinda, Faridkot, Ferozepur, Mansa, Muktsar and Ropar Arsenic (above 0.05mg/l) Amritsar, Tarantaran, Kapurthala, Ropar, Mansa Iron (>1.0mg/l) Amritsar, Bhatinda, Gurdaspur, Hoshiarpur, Jallandhar, Kapurthala, Ludhiana, Mansa, Nawanshahr, -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

June 18, 2002 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1081 Such a war would be useless, dangerous, and Sikhs should take this opportunity to re- leased. The U.S. government recently added a disaster for Pakistan, India, the minorities of claim our lost sovereignty and liberate our India to its ‘‘watch list’’ of violators of reli- the subcontinent, and the world. homeland, Punjab, Khalistan, from Indian gious freedom. It should impose sanctions to Many South Asia’s watchers speculate that occupation. stop the oppression of Sikhs, Christians, L.K. Advani has said that when Kashmir Muslims, and others. India needs a war to keep its multinational goes, India will fall apart, and he is right. We Jaswant Singh Khalra, who exposed the empire together and to divert attention away must take advantage of this situation to re- government killing of Sikhs in fake encoun- from its other internal problems. They have claim our lost sovereignty. Sovereignty is ters, became a victim of the Indian police even speculated that India’s collapse is not a our birthright. The Guru gave sovereignty to himself. He was kidnapped outside his house fantasy, and that even L.K. Advani, the militant the Khalsa Panth. (‘‘In grieb Sikhin ko deon and murdered in police custody. Even Akal Hindu Home Minister of India, is worried about Patshahi.’’) Banda Singh Baliadur estab- Takht Jathedar Sardar Gurdev Singh India’s territorial integrity. lished the first Khalsa rule in Punjab from Kaunke was murdered by SSP Swaran Singh However, a war in South Asia could become 1710 to 1716. Then there was a period of perse- Ghotna and then his body was disposed of. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

GREATER MOHALI AREA 1)EVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (IT CITY Landpooling Commercial Draw Result of 20 Sq

GREATER MOHALI AREA 1)EVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (IT CITY Landpooling commercial draw result of 20 sq. Yds dated 17-08-2021) Draw LOI Code File No Current Owner Father Name Sector Big Attributes Pocket sr no. no. Name Booth no. 1 3901 82-83/0626 Shaveta Gulati Sunit Gulati 66 beta 100 General B 2 3610 82-0488 Tejinder Singh Avtar Singh 83 alpha 12 General A 3 1171 LP/82-0210 Gurmit Singh Attma Singh 82 alpha 33 General A 4 1142 LP/82-0202 Nirlep kaur Nat Jagmohan 82 alpha 249 General D Singh 5 1268 LP/82-0257 Mandeep Kaur Satwinder 66 beta 40 Corner A Singh 6 1621 LP/82-0332 Dharampal Harinder 82 alpha 188 General D Singh Singh 7 506 LP/82-0073 Bimla Dagar Udayvir 83 alpha 6 General A Singh 8 1712 LP/82-0352 Mandeep Singh Kuldip Singh 66 beta 11 General A Sagoo Sagoo 9 552 LP/82-0172 Sukhdarshan Swaran Singh 82 alpha 7 General A Singh 10 996 LP/82-0138 Pavittar Singh Malkit Singh 82 alpha 219 General D 11 622 LP/82-0080 Vinod Bali Sh. M.L. Bali 66 beta 103 General B 12 777 LP/82-0244 Harinder Singh Boota Singh 82 alpha 226 Corner D 13 34859 82-83/0479 SurinderSingh Sh.Gurdev 82a1pha 264 General D Singh 14 1227 LP/82-0224 Rakesh Kumar Sita Ram 82 alpha 260 General D 15 68802 CLP/82/83- Ankita Sangwan Joginder 66 beta 90 General A 0151 Singh 16 75 LP/82-0010 Sandhya J.L. -

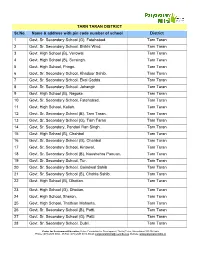

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

Brief Industrial Profile of Amritsar District

Brief Industrial Profile of Amritsar District MSME DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE Government of India, Ministry of MSME Industrial Area-‘B’ LUDHIANA-141 003 (Punjab) Telephone No.: 2531733-34-35 Fax: 091-0161-2533225 Email : [email protected] Website : www.msmedildh.gov.in Contents S. No. Topic 1. General Characteristics of the District 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 1.2 Topography 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 1.4 Forest 1.5 Administrative set up 2. District at a Glance 3. Industrial Scenario of District 3.1 Existing Status of Industrial Area in the District 3.2 Industry at a Glance 3.3 Year Wise Trend of Units Registered 3.4 Details Of Existing MSEs & Artisan Units In the District 3.5.1 Large Scale Enterprises / Public Sector Undertakings 3.5.2 Major Exportable Item 3.5.3 Growth Trends 3.5.4 Vendorisation / Ancillarisation of the Industry 3.6 Service Enterprises 3.6.1 Existing Service Sector 3.6.2 Potentials Areas for Service Sector 3.7 Unregistered Sector 3.8 Potential for New MSMEs 4. Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 4.1 Detail of Major Clusters 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 4.1.2 Service Sector 4.2 Details of Identified Cluster 5. General issues raised by Industrial Associations 6. Institutional Support 1 1. General Characteristics of the District Amritsar city situated in northern Punjab state of north-western India lies about 15 m iles (25 km ) east of the bor der with Pakistan. Am ritsar is an important city in Punjab and is a major commercial, cultural, and transportation centre. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1674 HON

E1674 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks August 1, 2007 INTRODUCTION OF THE UNI- Because of decades of refusal by Congress He has managed several successful local VERSAL PRE-KINDERGARTEN to approve the large sums necessary for uni- and State political campaigns. Mr. Pugh AND EARLY CHILDHOOD EDU- versal health coverage, the Universal Pre-K served as chair of the Saginaw County Rev- CATION ACT OF 2007 Act encourages school districts across the erend Jesse Jackson for President Committee United States to apply to the Department of in 1984 and 1988. Rev. Jesse Jackson won in HON. ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON Education for grants to establish three and Saginaw County in 1984. In 1988, again under OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA four-year-old kindergartens. Grants funded Mr. Pugh’s leadership, Jackson won the Sagi- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES under Title IV of the Elementary and Sec- naw district. Mr. Pugh served as a delegate to ondary Education Act, ESEA, would be avail- the National Democratic Convention in 1988 Tuesday, July 31, 2007 able to school systems which agree in turn to and 1992. Ms. NORTON. Madam Speaker, I am intro- use the experience acquired with the Federal His community involvement includes: found- ducing today the Universal Pre-kindergarten funding provided by my bill to then move for- ing board member of the Ruben Daniels Edu- and Early Childhood Education Act of 2007 ward, where possible, to phase in three and cational Foundation, member of Saginaw (Universal Pre-K) to begin the process of pro- four-year-old kindergartens for all children in County Mental Health Authority, chair of the viding universal, public school pre-kinder- the school district in regular classrooms with Saginaw Branch NAACP ACT–SO Program, garten education for every child, regardless of teachers equivalent to those in other grades member of Zion Missionary Baptist Church income. -

Census of India 2011

Census of India 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS PUNJAB CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations PUNJAB MOTIF GURU ANGAD DEV GURUDWARA Khadur Sahib is the sacred village where the second Guru Angad Dev Ji lived for 13 years, spreading the universal message of Guru Nanak. Here he introduced Gurumukhi Lipi, wrote the first Gurumukhi Primer, established the first Sikh school and prepared the first Gutka of Guru Nanak Sahib’s Bani. It is the place where the first Mal Akhara, for wrestling, was established and where regular campaigns against intoxicants and social evils were started by Guru Angad. The Stately Gurudwara here is known as The Guru Angad Dev Gurudwara. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 4 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 5 5 Brief History of the District 7 6 Administrative Setup 8 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 11 8 Important Statistics 12 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 16 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 21 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 29 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 37 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 45 (vi) Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract 47 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 133 Tables based on Households Amenities and Assets (Rural 10 Section –II /Urban) at District and Sub-District level.