JAMES DICKSON INNES ~ by Brian Davies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland City Art Gallery

Frances Hodgkins 14 auckland city art gallery modern european paintings in new Zealand This exhibition brings some of the modern European paintings in New Zealand together for the first time. The exhibition is small largely because many galleries could not spare more paintings from their walls and also the conditions of certain bequests do not permit loans. Nevertheless, the standard is reasonably high. Chronologically the first modern movement represented is Impressionism and the latest is Abstract Expressionism, while the principal countries concerned are Britain and France. Two artists born in New Zealand are represented — Frances Hodgkins and Raymond Mclntyre — the former well known, the latter not so well as he should be — for both arrived in Europe before 1914 when the foundations of twentieth century painting were being laid and the earlier paintings here provide some indication of the milieu in which they moved. It is hoped that this exhibition may help to persuade the public that New Zealand is not devoid of paintings representing the serious art of this century produced in Europe. Finally we must express our sincere thanks to private owners and public galleries for their generous response to requests for loans. P.A.T. June - July nineteen sixty the catalogue NOTE: In this catalogue the dimensions of the paintings are given in inches, height before width JANKEL ADLER (1895-1949) 1 SEATED FIGURE Gouache 24} x 201 Signed ADLER '47 Bishop Suter Art Gallery, Nelson Purchased by the Trustees, 1956 KAREL APPEL (born 1921) Dutch 2 TWO HEADS (1958) Gouache 243 x 19i Signed K APPEL '58 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by the Contemporary Art Society, 1959 JOHN BRATBY (born 1928) British 3 WINDOWS (1957) Oil on canvas 48x144 Signed BRATBY JULY 1957 Auckland City Art Gallery Presented by Auckland Gallery Associates, 1958 ANDRE DERAIN (1880-1954) French 4 LANDSCAPE Oil on canvas 21x41 J Signed A. -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Copyright Statement

COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. i ii REX WHISTLER (1905 – 1944): PATRONAGE AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY by NIKKI FRATER A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Humanities & Performing Arts Faculty of Arts and Humanities September 2014 iii Nikki Frater REX WHISTLER (1905-1944): PATRONAGE AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY Abstract This thesis explores the life and work of Rex Whistler, from his first commissions whilst at the Slade up until the time he enlisted for active service in World War Two. His death in that conflict meant that this was a career that lasted barely twenty years; however it comprised a large range of creative endeavours. Although all these facets of Whistler’s career are touched upon, the main focus is on his work in murals and the fields of advertising and commercial design. The thesis goes beyond the remit of a purely biographical stance and places Whistler’s career in context by looking at the contemporary art world in which he worked, and the private, commercial and public commissions he secured. In doing so, it aims to provide a more comprehensive account of Whistler’s achievement than has been afforded in any of the existing literature or biographies. This deeper examination of the artist’s practice has been made possible by considerable amounts of new factual information derived from the Whistler Archive and other archival sources. -

A Rocky Gorge, South of France SOLD REF: 2525 Artist: ALBERT RUTHERSTON

A Rocky Gorge, South of France SOLD REF: 2525 Artist: ALBERT RUTHERSTON Height: 25 cm (9 3/4") Width: 34.5 cm (13 1/2") Framed Height: 43 cm - 16 1/1" Framed Width: 52 cm - 20 1/2" 1 Sarah Colegrave Fine Art By appointment only - London and North Oxfordshire | England +44 (0)77 7594 3722 https://sarahcolegrave.co.uk/a-rocky-gorge-south-of-france 24/09/2021 Short Description ALBERT RUTHERSTON, RWS (1881-1953) A Rocky Gorge, South of France Watercolour and bodycolour Framed 25 by 34.5 cm., 9 ¾ by 13 ½ in. (frame size 43 by 52 cm., 17 by 20 ½ in.) Provenance: The artist and by descent to Gloria, Countess Bathurst. Born Albert Daniel Rothenstein, he was the youngest of the six children of Moritz and Bertha Rothenstein, German-Jewish immigrants who had settled in Bradford, Yorkshire in the 1860s. He and his siblings proved to be a hugely talented and artistic family, his elder brother became Sir William Rotherstein (1872-1945), the artist and director of the Royal College of Art; two of his other siblings, Charles Rutherston and Emily Hesslein, both accumulated major modern British and French art collections and his nephew Sir John Rothenstein was direct of the Tate Gallery. He was educated at Bradford Grammar School before moving to London in 1898 to study at the Slade School of Art where he became close friends with Augustus John and William Orpen. He met Walter Sickert during a painting holiday in France in 1900 and by introducing Sickert to Spencer Gove became instrumental in the beginning of the Camden Town Group. -

The EY Exhibition. Van Gogh and Britain

Life & Times Exhibition The EY Exhibition and his monumental Van Gogh and Britain London: a Pilgrimage. Tate Britain, London, Whistler’s Nocturnes 27 March 2019 to 11 August 2019 and Constable’s country landscapes also made a VINCENT IN LONDON considerable impression London seems to have been the springboard on him. Yet he did not for Vincent van Gogh’s creative genius. He start painting until he trained as an art dealer at Goupil & Cie in had unsuccessfully tried The Hague, coming to the company’s Covent his hand at teaching and Garden office in 1873, aged 20. He lodged in preaching. South London, initially in Brixton, and for a He returned to the short time stayed at 395 Kennington Road, Netherlands at the age of just a few minutes from my old practice 23, where, in 1880, after in Lambeth Walk. He soaked up London further unsatisfactory life and loved to read Zola, Balzac, Harriet forays into theology and Beecher Stowe, and, above all, Charles missionary work, his Dickens. This intriguing exhibition opens art dealer brother Theo movingly with a version of L’Arlésienne encouraged him to start (image right), in which Dickens’s Christmas drawing and painting. Stories and Uncle Tom’s Cabin lie on the Van Gogh’s earliest table. paintings were almost He became familiar with the work of pastiches of Dutch British illustrators and printmakers, and landscape masters, but, as he absorbed Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890), L’Arlésienne, 1890. Oil paint on canvas, 650 × also that of Gustav Doré (below is van 540 mm. -

View the Press Release

DAVIS & LANGDALE COMPANY, INC. 231 EAST 60TH STREET NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE 212 838 0333 FAX 212 752 7764 PRESS RELEASE / ART LISTING November 16, 2018 Woman in Green Coat and Black Hat Curled Up Sleeping Tortoise-Shell Cat Flowers and Foliage in Blue & Pink Vase Gouache on paper Wash and pencil on paper Gouache on paper 8 13/16 x 6 7/8 inches 8 5/8 x 9 7/8 inches 7 1/8 x 5 3/4 inches Probably executed1920s Executed 1904 - 1908 Probably executed during the late 1920s DAVIS & LANGDALE COMPANY, 231 EAST 60TH STREET, NEW YORK, announces its new exhibition: GWEN JOHN: WATERCOLORS AND DRAWINGS which will open Friday, November 16, and continue through Saturday, December 8, 2018. A reception will be held on Wednesday December 5, 2018 from 5pm – 7pm. This exhibition will be the final show at 231 East 60th Street; after January 1, 2019, Davis & Langdale will be open by appointment only at a new location. The exhibition will consist of twenty-five works on paper, all of which have just been released from the artist’s estate and have never been previously shown. They include gouaches of women and children in church, drawings of the poet and critic Arthur Symons and of the artist’s friend Chloe Boughton-Leigh, images of peasant boys and girls, watercolors of cats, still lifes, and landscapes. GWEN JOHN (1876 – 1939) is one of the foremost British artists of the twentieth century. Born in Wales, she was the sister of the also famous Augustus John. -

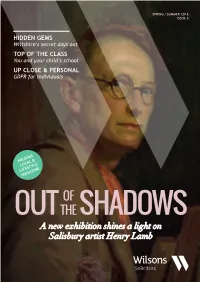

OF the CLASS You and Your Child’S School up CLOSE & PERSONAL GDPR for Individuals

SPRING / SUMMER 2018 ISSUE 5 HIDDEN GEMS Wiltshire’s secret days out TOP OF THE CLASS You and your child’s school UP CLOSE & PERSONAL GDPR for individuals WILSONS LEGAL & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE OF OUT THE SHADOWS A new exhibition shines a light on Salisbury artist Henry Lamb Beautiful Jewellery Independent Jewellers 12 Bridge Street, Salisbury, SP1 2LX 01722 324395 www.tribbecks.com COVER IMAGE: Self Portrait, 1932 Henry Lamb WELCOME veryone knows Wiltshire as the county of Stonehenge, Avebury and Salisbury Cathedral, all E of which are hugely rewarding places to visit. Yet sometimes taking the path less trodden can have its own memorable rewards, especially in a wonderful county with a rich history like ours. And that’s the gist of our feature on page 36 of this issue – Wiltshire’s Hidden Gems. Whether it’s an exquisite ancient earthworks like Figsbury Ring or a romantic ruin such as Old Wardour Castle (left) there’s something special round every corner. We also profile the artist Henry Lamb who spent most of his later years with his family in Coombe Bissett. An important 20th-century figurative painter, and co-founder of the Camden Town Group, Lamb is perhaps less well-known than some of his contemporaries, but a major exhibition of his work at the Salisbury Museum sets out to put that right. See our feature on page 24. Elsewhere in the magazine, the Wilsons team shares its insights with you on a number of legal matters. First, we take a look at the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and how it is giving us the opportunity to take control of our own personal data (p.8). -

Modern British and Irish Art Wednesday 28 May 2014

Modern British and irish art Wednesday 28 May 2014 MODERN BRITISH AND IRISH ART Wednesday 28 May 2014 at 14.00 101 New Bond Street, London duBlin Viewing Bids enquiries CustoMer serViCes (highlights) +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 London Monday to Friday 08.30 to 18.00 Sunday 11 May 12.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7447 4401 fax Matthew Bradbury +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Monday 12 May 9.00 - 17.30 To bid via the internet please +44 (0) 20 7468 8295 Tuesday 13 May 9.00 - 17.30 visit bonhams.com [email protected] As a courtesy to intending bidders, Bonhams will provide a london Viewing Please note that bids should be Penny Day written Indication of the physical New Bond Street, London submitted no later than 4pm on +44 (0) 20 7468 8366 condition of lots in this sale if a Thursday 22 May 14.00 - 19.30 the day prior to the sale. New [email protected] request is received up to 24 Friday 23 May 9.30 - 16.30 bidders must also provide proof hours before the auction starts. Saturday 24 May 11.00 - 15.00 of identity when submitting bids. Christopher Dawson This written Indication is issued Tuesday 27 May 9.30 - 16.30 Failure to do this may result in +44 (0) 20 7468 8296 subject to Clause 3 of the Notice Wednesday 28 May 9.30 - 12.00 your bid not being processed. [email protected] to Bidders. Live online bidding is available Ingram Reid illustrations sale number for this sale +44 (0) 20 7468 8297 Front cover: lot 108 21769 Please email [email protected] [email protected] Back cover: lot 57 with ‘live bidding’ in the subject Inside front cover: lot 13 Catalogue line 48 hours before the auction Jonathan Horwich Inside back cover: lot 105 £20.00 to register for this service Global Director, Picture Sales Opposite: lot 84 +44 (0) 20 7468 8280 [email protected] Please note that we are closed Monday 26 May 2014 for the Irish Representative Spring Bank Holiday Jane Beattie +353 (0) 87 7765114 iMportant inforMation [email protected] The United States Government has banned the import of ivory into the USA. -

Augustus John

Augustus John: An Inventory of His Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: John, Augustus, 1878-1961 Title: Augustus John Art Collection Dates: 1903-1946 Extent: 1 box (10 items) Abstract: The Collection consists of ten portraits on paper (drawings, etchings, and reproductive prints) of well-known English contemporaries of John, including James Joyce, Ottoline Morrell, and W. B. Yeats. Access: Open for research. A minimum of twenty-four hours is required to pull art materials to the Reading Room. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases (R938, R1252, R3785, R4731, R5180) and gift (R2767) Processed by: Helen Young, 1997 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin John, Augustus, 1878-1961 Biographical Sketch Augustus Edwin John was born January 4, 1878, at Tenby, Pembrokeshire, to Edwin William John and Augusta Smith. In 1894 he began four years of studies at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where he worked under Henry Tonks and Frederick Brown. During his time at the Slade School, John also studied the works of the Old Masters at the National Gallery. After suffering a head injury while swimming at Pembrokeshire in 1897, the quality of John's artwork, as well as his appearance and personality, changed. His methodical style became freer and bolder, and his work started to gain notice. In 1898, John won the Slade Prize for his Moses and the Brazen Serpent . John left the Slade School in 1898, and he held his first one-man exhibition in 1899 at the Carfax Gallery in London. Later that same year he traveled on the continent, part of the time with a group consisting of the artist brothers Sir William Rothenstein and Albert Rutherston, William Orpen, Sir Charles Conder, and Ida Nettleship (a fellow Slade student). -

The Role of the Royal Academy in English Art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P

The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20673/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version COWDELL, Theophilus P. (1980). The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk onemeia u-ny roiyiecnmc 100185400 4 Mill CC rJ o x n n Author Class Title Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB NOT FOR LOAN Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour Sheffield Haller* University Learning snd »T Services Adsetts Centre City Csmous Sheffield SI 1WB ^ AUG 2008 S I2 J T 1 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10702010 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10702010 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

1 All Work, No Play … : Representations of Child Labour In

All Work, No Play … : Representations of Child Labour in Films of the First World War Stella Hockenhull University of Wolverhampton During the First World War, even though cinema was still in its infancy, it was seen as a viable tool for propagandist purposes. Furthermore, despite the domination of battle scenes and fighting at the front, a number of Home Front films were also produced to encourage patriotism and to advertise the effort required by the populace to support the troops.1 Indeed, Home Front newsreels were seen by the Government as mobilising useful moral support through nationalism, and, notably, a number featured children in their campaign. However, unlike preceding imagery of childhood, particularly that which had dominated the work of film directors such as Cecil Hepworth (1874-1953), these films did not depict them as embodiments of innocence and in need of protection, nor were they sentimentalised or represented as victims.2 Instead, propaganda cinema of the First World War displayed infancy and youth in military style and as willing individuals ready to serve the nation; this was achieved by detailing their day to day activities in which they were seen as capable, and physically able to help with important tasks such as animal husbandry and food production. Indeed, depictions of children standing in line and operating in perfunctory fashion were habitually displayed, rather than engaged in play activities. and this chimed with the work of artists of the period, and contemporaneous and modernist art movements such as Vorticism.3 One such example, Even Children Help (1917), shows a group of schoolchildren working the land in an orderly and 1 mechanistic way, and Children Grow Vegetables (1914-18) is comprised of shots of disciplined adolescent gardeners, these children dedicated to their task, and demonstrating the correlation between food and survival. -

Manifestoes: a Study in Genre

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2003 Manifestoes: A Study in Genre Stevens Russell Amidon University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Amidon, Stevens Russell, "Manifestoes: A Study in Genre" (2003). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 682. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/682 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANIFESTOES: A STUDY IN GENRE BY STEVENS RUSSELL AMIDON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2003 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF STEVENS R. AMIDON APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professolf_J.,J:S~~~~:L:::~~~~~ ~-yab H; .,_,, ~ DEAN~- OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2003 Abstract: This project is a book-length study of the manifesto, which attempts to trace adaptations writers have made to the genre, beginning with the Luther's "95 Theses." From there I move to political manifestoes, including the "Twelve Articles of the Swabian Peasants and Marx and Engels' "Manifesto of the Communist Party," and then to the aesthetic manifestoes of modernism. Later I treat manifestoes of critique, examining texts by Virginia Woolf, Frank O'Hara, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and Donna Haraway, the Students for a Democratic Society and the Lesbian Avengers. While this project is a study of genre and influence, it is grounded in contemporary theories of social reproduction.