1 All Work, No Play … : Representations of Child Labour In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OF the CLASS You and Your Child’S School up CLOSE & PERSONAL GDPR for Individuals

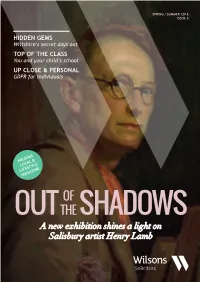

SPRING / SUMMER 2018 ISSUE 5 HIDDEN GEMS Wiltshire’s secret days out TOP OF THE CLASS You and your child’s school UP CLOSE & PERSONAL GDPR for individuals WILSONS LEGAL & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE OF OUT THE SHADOWS A new exhibition shines a light on Salisbury artist Henry Lamb Beautiful Jewellery Independent Jewellers 12 Bridge Street, Salisbury, SP1 2LX 01722 324395 www.tribbecks.com COVER IMAGE: Self Portrait, 1932 Henry Lamb WELCOME veryone knows Wiltshire as the county of Stonehenge, Avebury and Salisbury Cathedral, all E of which are hugely rewarding places to visit. Yet sometimes taking the path less trodden can have its own memorable rewards, especially in a wonderful county with a rich history like ours. And that’s the gist of our feature on page 36 of this issue – Wiltshire’s Hidden Gems. Whether it’s an exquisite ancient earthworks like Figsbury Ring or a romantic ruin such as Old Wardour Castle (left) there’s something special round every corner. We also profile the artist Henry Lamb who spent most of his later years with his family in Coombe Bissett. An important 20th-century figurative painter, and co-founder of the Camden Town Group, Lamb is perhaps less well-known than some of his contemporaries, but a major exhibition of his work at the Salisbury Museum sets out to put that right. See our feature on page 24. Elsewhere in the magazine, the Wilsons team shares its insights with you on a number of legal matters. First, we take a look at the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and how it is giving us the opportunity to take control of our own personal data (p.8). -

The Role of the Royal Academy in English Art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P

The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20673/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version COWDELL, Theophilus P. (1980). The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk onemeia u-ny roiyiecnmc 100185400 4 Mill CC rJ o x n n Author Class Title Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB NOT FOR LOAN Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour Sheffield Haller* University Learning snd »T Services Adsetts Centre City Csmous Sheffield SI 1WB ^ AUG 2008 S I2 J T 1 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10702010 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10702010 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

A Chronology of Wyndham Lewis

A Chronology of Wyndham Lewis 1882 Percy Wyndham Lewis born, Amherst Nova Scotia 1888-93 Isle of Wight 1897-8 Rugby School 1898-1901 Slade School of Art (expelled) 1902 Visits Madrid with Spencer Gore, copying Goya in the Prado 1904-6 Living in Montparnasse, Paris. Meets Ida Vendel (‘Bertha’ in Tarr) 1906 Munich (February – July). 1906-7 Paris 1907 Ends relationship with Ida 1908 – 11 Writes first draught of Tarr, a satirical depiction of Bohemian life in Paris 1908 London 1909 First published writing, ‘The “Pole”’, English Review 1911 Member of Camden Town Group. ‘Cubist’ self-portrait drawings 1912 Decorates ‘Cave of the Golden Calf’ nightclub Exhibits ‘cubist’ paintings and illustrations to Timon of Athens at ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’ 1913 Joins Fry’s Omega Workshops; walks out of Omega in October with Frederick Etchells, Edward Wadsworth and Cuthbert Hamilton after quarrel with Fry. Portfolio, Timon of Athens published. Begins close artistic association with Ezra Pound 1914 Director, ‘Rebel Art Centre’, Great Ormond Street (March – July) Dissociates self from Futurism and disrupts lecture by Marinetti at Doré Gallery (June) Vorticism launched in Blast (July; edited by Lewis) Introduced to T. S. Eliot by Pound 1915 Venereal infection; Blast no. 2 (June); completes Tarr 1916-18 War service in Artillery, including Third Battle of Ypres and as Official War Artist for Canada and Great Britain 1918-21 With Iris Barry, with whom he has two children 1918 Tarr published. It is praised in reviews by Pound, Eliot and Rebecca West Meets future wife, Gladys Hoskins 1919 Paints A Battery Shelled. -

Manifestoes: a Study in Genre

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2003 Manifestoes: A Study in Genre Stevens Russell Amidon University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Amidon, Stevens Russell, "Manifestoes: A Study in Genre" (2003). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 682. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/682 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANIFESTOES: A STUDY IN GENRE BY STEVENS RUSSELL AMIDON A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2003 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF STEVENS R. AMIDON APPROVED: Dissertation Committee: Major Professolf_J.,J:S~~~~:L:::~~~~~ ~-yab H; .,_,, ~ DEAN~- OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 2003 Abstract: This project is a book-length study of the manifesto, which attempts to trace adaptations writers have made to the genre, beginning with the Luther's "95 Theses." From there I move to political manifestoes, including the "Twelve Articles of the Swabian Peasants and Marx and Engels' "Manifesto of the Communist Party," and then to the aesthetic manifestoes of modernism. Later I treat manifestoes of critique, examining texts by Virginia Woolf, Frank O'Hara, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and Donna Haraway, the Students for a Democratic Society and the Lesbian Avengers. While this project is a study of genre and influence, it is grounded in contemporary theories of social reproduction. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1953-54

Contemporary Art Society Contemporary Art Society, Tate Gallery, Millbank, S.W.I Patron Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Executive Committee Raymond Mortimer, Chairman Sir Colin Anderson, Hon. Treasurer E. C. Gregory, Hon. Secretary Edward Le Bas, R.A. Sir Philip Hendy W. A. Evill Eardley Knollys Hugo Pitman Howard Bliss Mrs. Cazalet Keir Loraine Conran Sir John Rothenstein, C.B.E. Eric Newton Peter Meyer Assistant Secretary Denis Mathews Hon. Assistant Secretary Pauline Vogelpoel Annual Report 19534 Contents The Chairman's Report Acquisitions, Loans and Presentations The Hon. Treasurer's Report Auditor's Accounts Future Occasions Bankers Orders and Deeds of Covenant 10 Oft sJT CD -a CD as r— ««? _s= CO CO "ecd CO CO CD eds tcS_ O CO as. ••w •+-» ed bT CD ss_ O SE -o o S ed cc es ed E i Gha e th y b h Speec This year the Society can boast of having been more active than privileged to visit the private collections of Captain Ernest ever before in its history. We have, alas, not received by donation Duveen, Mrs. Edward Hulton, Mrs. Oliver Parker and Mrs. Lucy or legacy any great coliection of pictures or a nice, fat sum of Wertheim. We have been guests also at a number of parties, for money. Sixty members have definitely abandoned us, and a good which we have to thank the Marlborough Fine Art Ltd., (who many others, you will be surprised to hear, have without resigning, have entertained us twice), the Redfern Gallery, Messrs. omitted to pay their subscription. -

December 2014 Newsletter

1/13/2015 The London Group - December 2014 newsletter Subscribe Share Past Issues Translate View this email in your brow ser December 2014 Newsletter Introduction from the President With the closing of our Southampton exhibition and our Group photograph on the steps of Tate Britain we have come to the grand finale of our Centenary, having ingeniously managed to keep the celebrations going for two years. Thank you to the 59 members who came along to Tate Britain on the sunny afternoon of 19 October. It was very moving to see so many members and how much the Group means to everyone. What a memorable occasion. Thank you to Mark Dickens for http://us9.campaign-archive2.com/?u=f1eaa1804f7a0d93091ce5203&id=78b9dad04c&e=ae47cb2912 1/16 1/13/2015 The London Group - December 2014 newsletter planning and organising it and to the photographer, Jayne Taylor. Our triumphant four month exhibition From David Bomberg to Paula Rego: The London Group in Southampton at Southampton City Art Gallery ended on 1 November. We are very proud to have shown in one of the country’s major regional art galleries and Southampton has the largest collection of The London Group members’ work apart from the Tate. We were given a warm welcome by Tim Craven, Curator of Art, and his staff at the Private View on 17 July and we had fun travelling by coach, meticulously organised by Tommy Seaward. The exhibition included a record number of current members’ works, curated by Samantha Jarman and Bryan Benge, shown in an adjacent gallery to historic works from Southampton’s collection, selected and curated by Victoria Rance and David Redfern. -

Art Appreciation 11-07-19 Report. 1 – Anne Williams : Pere Borrell Del Caso

Art Appreciation 11-07-19 Report. 1 – Anne Williams: Pere Borrell del Caso (1835 – 1910); ‘Escaping Criticism’ (1874); oil on canvas; location – Banco de Espana, Madrid. Anne gave a short biography of Borrell del Caso: a Catalan artist, the son of a carpenter, he got his artistic training at the renowned Escola de la Llotja, in Barcelona, working as a chest maker to pay for his classes. As a young man Borrell distanced himself from the Romanticism that dominated the education at the academy. He rejected the idealization and insincerity that, in his eyes, were so typical of Romantic art and chose to change to the novel style of Realism. He founded his own art academy, the Sociedad de Bellas Artes. Here, students were encouraged to work ‘en plein air’, a rare phenomenon in those days. The painting is in the style of trompe-l’oeil, which means ‘the eye is deceived’. This painting shows an ill-clothed boy who clambers out of a picture frame to enter the world outside it. The symbolism of the painting tells of the artist’s need to escape the confinement of traditional artistic styles. Comments about the painting included: the boy’s eyes portray that he is listening hard, and possibly is being startled; the ‘picture frame’ appears three-dimensional; the boy is grubby and there is realistic detail in the painting. 2 – Dianne Bullough: Ivan Lackovic-Croata (1932 – 2004); ‘Winter’, ‘Winter Landscapes’, ‘Zima’. Dianne began by giving a short biography: Ivan Lacković Croata was a Croatian painter. Born to a peasant family in the village of Batinske near Kalinovac, after completing his primary education, he worked as a labourer in fields and forests. -

British Paintings & Works on Paper 1890–1990

British Paintings & Works on Paper 1890–1990 LISS FINE ART TWENTIETH-CENTURY MYTHS Twentieth-century British art is too often presented as a stylistic progression. top right In fact, throughout the century, a richness and diversity of styles co-existed. Albert de Belleroche, Head of This catalogue is presented in chronological order and highlights both some a woman – three quarter profile, late 1890s (cat. 62) extraordinary individual pictures and the interdependent nature of the artistic ground from which they flowered. bottom right Michael Canney, Sidefold V, Abstraction may well have been the great twentieth century art invention, yet 1985 (cat. 57) most of its leading artists were fed by both the figurative and abstract traditions and the discourse between them. Sir Thomas Monnington,the first President of the Royal Academy to make abstract paintings, acknowledged the importance of this debate, when he declared,‘You cannot be a revolutionary and kick against the rules unless you learn first what you are kicking against. Some modern art is good, some bad, some indifferent. It might be common, refined or intelligent.You can apply the same judgements to it as you can to traditional works’.1 Many of the artists featured in this catalogue – Monnington, Jas Wood, Banting, Colquhoun, Stephenson, Medley, Rowntree,Vaughan, Canney and Nockolds – moved freely between figurative and abstract art. It was part of their journey. In their ambitious exploration to find a pure art that went beyond reality, they often stopped, or hesitated, and in many cases returned to figurative painting. Artists such as Bush, Knights, Kelly and Cundall remained throughout their lives purely figurative.Their best work, however, is underpinned by an economy of design, which not only verges on the abstract, but was fed by the compositional purity developed by the pursuit of abstraction. -

Woolf and the Art of Exploration Helen Southworth

Clemson University TigerPrints Woolf Selected Papers 2006 Woolf and the Art of Exploration Helen Southworth Elisa Kay Sparks Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cudp_woolfe Recommended Citation Woolf and the Art of Exploration: Selected Papers from the Fifteenth International Conference on Virginia Woolf, edited by Helen Southworth and Elisa Kay Sparks (Clemson, SC: Clemson University Digital Press, 2006), xiv, 254 pp. ISBN 0-9771263-8-2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Woolf Selected Papers by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Woolf and the Art of Exploration Selected Papers from the Fifteenth International Conference on Virginia Woolf Woolf and the Art of Exploration Selected Papers from the Fifteenth International Conference on Virginia Woolf Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon 9–12 June 2005 Edited by Helen Southworth and Elisa Kay Sparks A full-text digital version of this book is available on the Internet, at the Center for Vir- ginia Woolf Studies, California State University, Bakersfi eld. Go to http://www.csub.edu/ woolf_center and click the Publications link. Works produced at Clemson University by the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, including Th e South Carolina Review and its themed series “Virginia Woolf International,” may be found at our Web site: http://www. clemson.edu/caah/cedp. Contact the director at 864-656-5399 for information. Copyright 2006 by Clemson University ISBN 0-9771263-8-2 Published by Clemson University Digital Press at the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository White, Corinne Jane How has the art education that I have received impacted on my practice as an art maker? Original Citation White, Corinne Jane (2015) How has the art education that I have received impacted on my practice as an art maker? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/24471/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ HOW HAS THE ART EDUCATION THAT I HAVE RECIEVED IMPACTED ON MY PRACTICE AS AN ART MAKER? By CORINNE J WHITE Thesis Submitted to the University of Huddersfield in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts January 2015 1 ABSTRACT This thesis is a written account of my analysis of the art education that I received during my undergraduate Interdisciplinary Art and Design BA(hon)s degree and University Campus Barnsley. -

The Great War and After,1910-1930

A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN This two-hour talk is part of a series of twenty talks on the works of art displayed in Tate Britain, London, in June 2017. Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain. References and Copyright • The talk is given to a small group of people and all the proceeds, after the cost of the hall is deducted, are given to charity. • My sponsored charities are Save the Children and Cancer UK. • Unless otherwise mentioned all works of art are at Tate Britain and the Tate’s online notes, display captions, articles and other information are used. • Each page has a section called ‘References’ that gives a link or links to sources of information. • Wikipedia, the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Khan Academy and the Art Story are used as additional sources of information. • The information from Wikipedia is under an Attribution-Share Alike Creative Commons License. • Other books and articles are used and referenced. • If I have forgotten to reference your work then please let me know and I will add a reference or delete the information. 1 A STROLL THROUGH TATE BRITAIN • The Aesthetic Movement, 1860-1880 • Late Victorians, 1880-1900 • The Edwardians, 1890-1910 • The Great War and After, 1910-1930 • The Interwar Years, 1930s • World War II and After, 1940-1960 • Pop Art & Beyond, 1960-1980 • Postmodern Art, 1980-2000 • The Turner Prize • Summary West galleries are 1540, 1650, 1730, 1760, 1780, 1810, 1840, 1890, 1900, 1910 East galleries are 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 Turner Wing includes Turner, Constable, Blake and Pre-Raphaelite drawings Agenda 1. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1955-56

The Contemporary Art Society • The Contemporary Art Society, Tate Gallery, Millbank SWI Patron Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother Executive Committee Raymond Mortimer (Chairman) Peter Meyer (Hon. Treasurer) Loraine Conran (Hon. Secretary) Sir Colin Anderson Sir Philip Hendy W. A. Evill E. C. Gregory Eardley Knollys Howard Bliss Mrs. Cazalet-Keir Sir John Rothenstein, C.B.E. Eric Newton Mrs. Oliver Parker A. B. Lousada Dr. Alastair Hunter Organising Secretary Pauline Vogelpoel Chairman's Report The cheerful report on the year 1956 that I am privileged to offer you is defaced by one black spot: Mr. Denis Mathews, who had been our Assistant Secretary for ten years, resigned in the Spring. He wished to give all his time to painting, and as I greatly admire his gift I must applaud as well as regret his decision. By his enthusiasm, enterprise, tact and imagination as well as by his patient industry he did far more than anybody else to revive this Society, and on your behalf I wish to express the deepest gratitude. The Committee elected in his place as Organising Secretary, Miss Pauline Vogelpoel, who had been working as his assistant: her abilities have already proved even greater than we had hoped. She is now receiving some valuable help from Mrs. Meninsky. The Exhibition of paintings and sculpture depicting "The Seasons", which had been organised by the Society, was housed in the Tate by the generous permission of the Director and Trustees. Forty-four painters and thirteen sculptors accepted our invitation. Their works attracted nearly thirteen thousand visitors. The Sub-Committee appointed for the purpose, purchased for the Society paintings by Josef Herman, Patrick Heron, Derek Hill, Mary Kessell and William Scott, and bronzes by Reg Butler, F.