Wyndham Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Sunfly (All) Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Comic Relief) Vanessa Jenkins & Bryn West & Sir Tom Jones & 3OH!3 Robin Gibb Don't Trust Me SFKK033-10 (Barry) Islands In The Stream SF278-16 3OH!3 & Katy Perry £1 Fish Man Starstrukk SF286-11 One Pound Fish SF12476 Starstrukk SFKK038-10 10cc 3OH!3 & Kesha Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 My First Kiss SFKK046-03 Dreadlock Holiday SFHT004-12 3SL I'm Mandy SF079-03 Take It Easy SF191-09 I'm Not In Love SF001-09 3T I'm Not In Love SFD701-6-05 Anything FLY032-07 Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Anything SF049-02 Things We Do For Love, The SFMW832-11 3T & Michael Jackson Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Why SF080-11 1910 Fruitgum Company 3T (Wvocal) Simon Says SF028-10 Anything FLY032-15 Simon Says SFG047-10 4 Non Blondes 1927 What's Up SF005-08 Compulsory Hero SFDU03-03 What's Up SFD901-3-14 Compulsory Hero SFHH02-05-10 What's Up SFHH02-09-15 If I Could SFDU09-11 What's Up SFHT006-04 That's When I Think Of You SFID009-04 411, The 1975, The Dumb SF221-12 Chocolate SF326-13 On My Knees SF219-04 City, The SF329-16 Teardrops SF225-06 Love Me SF358-13 5 Seconds Of Summer Robbers SF341-12 Amnesia SF342-12 Somebody Else SF367-13 Don't Stop SF340-17 Sound, The SF361-08 Girls Talk Boys SF366-16 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME SF390-09 Good Girls SF345-07 UGH SF360-09 She Looks So Perfect SF338-05 2 Eivissa She's Kinda Hot SF355-04 Oh La La La SF114-10 Youngblood SF388-08 2 Unlimited 50 Cent No Limit FLY027-05 Candy Shop SF230-10 No Limit SF006-05 Candy Shop SFKK002-09 No Limit SFD901-3-11 In Da -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

BAAQMD AB&I 05.07.21 MA Transcribed 5.13.21

BAAQMD_AB&I_05.07.21_MA_Transcribed_5.13.21 Aneesh Rana (Facilitator): [00:00:01] Welcome. Good evening, everyone. You have joined the virtual workshop on the Air District’s Draft Health Risk Assessment of AB&I Foundry. At this at this time, I'd like to ask everybody, please mute themselves. This workshop is being recorded. My name is Aneesh Rana. I work in the Air District's Community Engagement Office. Before we get started, I'm going to go over some of the Zoom and other technical features for the meeting this evening. For those of you joining via a Web browser on your computer, smartphone or tablet, you will see icons along the bottom of your screen by clicking the two icons on the left corner, you can mute and unmute your microphone and turn the camera on your device on and off. If you move down the bar to your right, you will find the participants icon, by clicking this icon you can rename yourself, which we’d like you to do now so we can better identify you if you wish to speak later during the workshop. This is also where you can raise your hand to indicate that you wish to speak. If you are dialing into the meeting with your phone, you can dial star nine to raise your hand and then star nine again to lower it. Aneesh Rana (Facilitator): [00:01:13] Moving further down the bar, to your right, you'll find the chat icon. You can use this feature to submit questions or comments during the question and answer and public comment periods. -

With State Cash on the Way, Work to Accelerate at The

Serving our communities since 1889 — www.chronline.com Big Sweep Napavine Boys, Girls Top Onalaska / Sports 1 $1 Early Week Edition Tuesday, April 19, 2016 Catering to Catrina Ace at Northern State Friends, Community Members Come Together 2010 W.F. West Graduate Carves Out a Role to Raise Money for Business Owner / Life 1 Years After Tommy John Surgery / Sports 1 Warm With State Cash on the Way, Weather Work to Accelerate at the Fox ‘Smashes’ Previous Records MORE TO COME: Another Day of Heat in Forecast By Justyna Tomtas [email protected] A blast of hot, summer-like weather broke records Monday, and there is more to come. According to Andy Haner, meteorologist with the Nation- al Weather Service in Seattle, temperatures in the Southwest Washington area were hotter than any previous measurement at this time of the year. An observation site at a De- partment of Natural Resources facility off of the Rush Road exit on Interstate 5 recorded the temperature in Chehalis at 91 degrees Monday. Haner said he would be surprised if that num- ber did not break a previously set record, although numbers were Pete Caster / not available for Lewis County’s [email protected] record temperatures. Scott White, president of the nonproit Historic Fox Theatre Restorations, shows the remodeled women's bathroom on the second loor of the theater in Centralia on Monday afternoon. The theatre restoration project was awarded $250,000 in this year's supplemental capital budget, which was signed by Gov. Jay Inslee on please see WARM, page Main 11 Monday afternoon. -

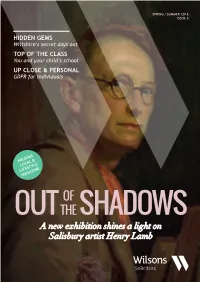

OF the CLASS You and Your Child’S School up CLOSE & PERSONAL GDPR for Individuals

SPRING / SUMMER 2018 ISSUE 5 HIDDEN GEMS Wiltshire’s secret days out TOP OF THE CLASS You and your child’s school UP CLOSE & PERSONAL GDPR for individuals WILSONS LEGAL & LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE OF OUT THE SHADOWS A new exhibition shines a light on Salisbury artist Henry Lamb Beautiful Jewellery Independent Jewellers 12 Bridge Street, Salisbury, SP1 2LX 01722 324395 www.tribbecks.com COVER IMAGE: Self Portrait, 1932 Henry Lamb WELCOME veryone knows Wiltshire as the county of Stonehenge, Avebury and Salisbury Cathedral, all E of which are hugely rewarding places to visit. Yet sometimes taking the path less trodden can have its own memorable rewards, especially in a wonderful county with a rich history like ours. And that’s the gist of our feature on page 36 of this issue – Wiltshire’s Hidden Gems. Whether it’s an exquisite ancient earthworks like Figsbury Ring or a romantic ruin such as Old Wardour Castle (left) there’s something special round every corner. We also profile the artist Henry Lamb who spent most of his later years with his family in Coombe Bissett. An important 20th-century figurative painter, and co-founder of the Camden Town Group, Lamb is perhaps less well-known than some of his contemporaries, but a major exhibition of his work at the Salisbury Museum sets out to put that right. See our feature on page 24. Elsewhere in the magazine, the Wilsons team shares its insights with you on a number of legal matters. First, we take a look at the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and how it is giving us the opportunity to take control of our own personal data (p.8). -

Song Title Version 1 More Time Daft Punk 5,6,7,8 Steps All 4 L0ve Color Me Badd All F0r Y0u Janet Jackson All That I Need Boyzon

SONG TITLE VERSION 1 MORE TIME DAFT PUNK 5,6,7,8 STEPS ALL 4 L0VE COLOR ME BADD ALL F0R Y0U JANET JACKSON ALL THAT I NEED BOYZONE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ACE OF BASE ALWAYS ERASURE ANOTHER NIGHT REAL MCCOY BABY CAN I HOLD YOU BOYZONE BABY G0T BACK SIR MIX-A-LOT BAILAMOS ENRIQUE IGLESIAS BARBIE GIRL AQUA BLACK CAT JANET JACKSON BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, BOOM!! VENGABOYS BOP BOP BABY WESTUFE BRINGIT ALL BACK S CLUB 7 BUMBLE BEE AQUA CAN WE TALK CODE RED CAN'T BE WITH YOU TONIGHT IRENE CANT GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD KYLIE MINOGUE CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE UB40 CARTOON HEROES AQUA C'ESTLAVIE B*WITCHED CHIQUITITA ABBA CLOSE TO HEAVEN COLOR ME BADD CONTROL JANET JACKSON CRAZY FOR YOU MADONNA CREEP RADIOHEAD CRY FOR HELP RICK ASHLEY DANCING QUEEN ABBA DONT CALL ME BABY MADISON AVENUE DONT DISTURB THIS GROOVE THE SYSTEM DONT FOR GETTO REMEMBER BEE GEES DONT LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD SANTA ESMERALDA DONT SAY YOU LOVE ME M2M DONT TURN AROUND ACE OF BASE DONT WANNA LET YOU GO FIVE DYING INSIDE TO HOLDYOU TIMMY THOMAS EL DORADO GOOMBAY DANCE BAND ELECTRIC DREAMS GIORGIO MORODES EVERYDAY I LOVE YOU BOYZONE EVERYTHING M2M EVERYTHING COUNTS DEPECHE MODE FAITHFUL GO WEST FATHER AND SON BOYZONE FILL ME IN CRAIG DAVID FIRST OF MAY BEE GEES FLYING WITHOUT WINGS WESTLIFE FOOL AGAIN WESTLIFE FOR EVER AS ONE VENGABOYS FUNKY TOWN UPS INC GET DOWN TONIGHT KC & THE SUNSHINE BAND GET THE PARTY STARTED PINK GET UP (BEFORE THE NIGHT IS OVER) TECHNOTRONIC GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY SONG BONEY M. -

Former SEAL from Jesup Motivates Atlanta Braves / Page 11A M M M

Former SEAL from Jesup motivates Atlanta Braves / Page 11A M M M ................................................... INDEX OBITUARIES/2A INSIDE / 8A WEATHER / 2A HI: 72 5-6B K Bettye Perkins LOW: 52 Classifieds1-2B K TODAY:.......................................................................................................... Partly Cloudy Phillip DeBrosse WCHS Dr. Daly 4-5A K April 16-17, Linda O’Neal Opinions2B tennis teams 2016 Socials8-9A Sports Volume 152 win region Number 31 Drop us a message online at: [email protected] or visit our Web site at: www.thepress-sentinel.com Jesup, Georgia 31545 Saturday-Sunday, April 16-17, 2016 00 .........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................$1 Both new Remembering crime victims schools on track By Drew Davis STAFF WRITER Both of the new ele- DERBY WATERS / Staff mentary schools being State Sen. Tommie Williams, left, thanks the audience built in Wayne County for support during his 18 years in Georgia Senate, while remain on schedule. State Reps. Chad Nimmer, center, and Bill Werkheiser School Superintendent listen. The legislators answered questions about the Jay Brinson reported to most recent legislative term in a session led by Steven the Board of Education -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Homestar Karaoke Song Book

HomeStar Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 10cc Avril Lavigne Good Morning Judge HSW216-04 Sk8er Boi HSW001-07 2 Play B.A. Robertson So Confused HSW022-10 Bang Bang HSG011-08 50 Cent Bang Bang HSW215-01 In Da Club HSG005-05 Knocked It Off HSG011-10 In Da Club HSW013-06 Knocked It Off HSW215-04 50 Cent & Nate Dogg Kool In The Kaftan HSG011-11 21 Questions HSW013-01 Kool In The Kaftan HSW215-05 ABBA To Be Or Not To Be HSG011-12 Chiquitita HSW257-01 To Be Or Not To Be HSW215-09 Chiquitita SFHS104-01 B.A. Robertson & Maggie Bell Dancing Queen HSW251-04 Hold Me HSG011-09 Does Your Mother Know HSW252-01 Hold Me HSW215-02 Fernando HSW257-03 B2K & P. Diddy Fernando SFHS104-02 Bump, Bump, Bump HSW001-02 Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) HSW257-04 Baby Bash Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) SFHS104-04 Suga Suga HSW024-09 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do HSW252-03 Bachelors, The I Have A Dream HSW258-01 Chapel In The Moonlight HSW205-03 I Have A Dream SFHS104-05 I Wouldn't Trade You For The World HSW205-09 Knowing Me, Knowing You HSW257-07 Love Me With All Of Your Heart HSW206-02 Knowing Me, Knowing You SFHS104-06 Ramona HSW206-06 Mama Mia HSW251-07 Bad Manners Money, Money, Money HSW252-05 Buona Sara HSW204-02 Name Of The Game, The HSW258-09 Hey Little Girl HSW204-05 Name Of The Game, The SFHS104-13 Just A Feeling HSG011-03 S.O.S. -

3. 10 SHANTY � Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4

Disc Bola 1. Judika Sakura (4:12) 2. Firman Esok Kan Masih Ada (3:43) 3. 10 SHANTY Mencari Cinta Sejati (4:05) 4. 14 J ROCK Topeng Sahabat (4:53) 5. Tata AFI Junior feat Rio Febrian There's A Hero (3:26) 6. DSDS Cry On My Shoulder (3:55) 7. Glenn Pengakuan Lelaki Ft.pazto (3:35) 8. Glenn Kisah Romantis (4:23) 9. Guo Mei Mei Lao Shu Ai Da Mi Lao Shu Ai Da Mi (Original Version) (4:31) 10. Indonesian Idol Cinta (4:30) 11. Ismi Azis Kasih (4:25) 12. Jikustik Samudra Mengering (4:24) 13. Keane Somewhere Only We Know (3:57) 14. Once Dealova (4:25) 15. Peterpan Menunggu Pagi [Ost. Alexandria] (3:01) 16. PeterPan Tak Bisakah (3:33) 17. Peterpan soundtrack album menunggu pagi (3:02) 18. Plus One Last Flight Out (3:56) 19. S Club 7 Have You Ever (3:19) 20. Seurieus Band Apanya Dong (4:08) 21. Iwan Fals Selamat Malam, Selamat Tidur Sayang (5:00) 22. 5566 Wo Nan Guo (4:54) 23. Aaron Kwok Wo Shi Bu Shi Gai An Jing De Zou Kai (3:57) 24. Abba Chiquitita (5:26) 25. Abba Dancing Queen (3:50) 26. Abba Fernando (4:11) 27. Ace Of Base The Sign (3:09) 28. Alanis Morissette Uninvited (4:36) 29. Alejandro Sanz & The Corrs Me Iré (The Hardest Day) (4:26) 30. Andy Lau Lian Xi (4:24) 31. Anggun Look Into Yourself (4:06) 32. Anggun Still Reminds Me (3:50) 33. Anggun Want You to Want Me (3:14) 34. -

The Role of the Royal Academy in English Art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P

The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. COWDELL, Theophilus P. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20673/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version COWDELL, Theophilus P. (1980). The role of the Royal Academy in English art 1918-1930. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk onemeia u-ny roiyiecnmc 100185400 4 Mill CC rJ o x n n Author Class Title Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB NOT FOR LOAN Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour Sheffield Haller* University Learning snd »T Services Adsetts Centre City Csmous Sheffield SI 1WB ^ AUG 2008 S I2 J T 1 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10702010 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10702010 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Making Metadata: the Case of Musicbrainz

Making Metadata: The Case of MusicBrainz Jess Hemerly [email protected] May 5, 2011 Master of Information Management and Systems: Final Project School of Information University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 Making Metadata: The Case of MusicBrainz Jess Hemerly School of Information University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected] Summary......................................................................................................................................... 1! I.! Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 2! II.! Background ............................................................................................................................. 4! A.! The Problem of Music Metadata......................................................................................... 4! B.! Why MusicBrainz?.............................................................................................................. 8! C.! Collective Action and Constructed Cultural Commons.................................................... 10! III.! Methodology........................................................................................................................ 14! A.! Quantitative Methods........................................................................................................ 14! Survey Design and Implementation.....................................................................................