The Eton Choirbook: Its Institutional and Historical Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

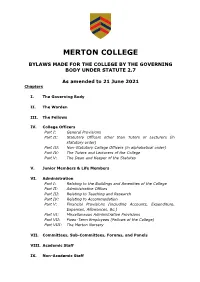

Merton College Bylaws As at 2021-06-21

MERTON COLLEGE BYLAWS MADE FOR THE COLLEGE BY THE GOVERNING BODY UNDER STATUTE 2.7 As amended to 21 June 2021 Chapters I. The Governing Body II. The Warden III. The Fellows IV. College Officers Part I: General Provisions Part II: Statutory Officers other than Tutors or Lecturers (in statutory order) Part III: Non-Statutory College Officers (in alphabetical order) Part IV: The Tutors and Lecturers of the College Part V: The Dean and Keeper of the Statutes V. Junior Members & Life Members VI. Administration Part I: Relating to the Buildings and Amenities of the College Part II: Administrative Offices Part III: Relating to Teaching and Research Part IV: Relating to Accommodation Part V: Financial Provisions (including Accounts, Expenditure, Expenses, Allowances, &c.) Part VI: Miscellaneous Administrative Provisions Part VII: Fixed-Term Employees (Fellows of the College) Part VIII: The Merton Nursery VII. Committees, Sub-Committees, Forums, and Panels VIII. Academic Staff IX. Non-Academic Staff X. The Common Table, The Common Room, College Dinners and Entertainment Part I: The Common Room Part II: The Common Table Part III: College Dinners and Entertainment XI. Discipline and Fitness to Study of Junior Members XI A: Academic Discipline XI B: Discipline for Serious Misconduct XI C: Failure in the First Public Examination XI D: Suspension and Fitness to Study Appendices A. Bylaw VI.1(b): Commemoration of Benefactors B. Bylaw VI.39: Policies adopted by the Governing Body 1. EJRA Policy 2012 2. Information Security a. Information Security Policy 2018 b. Data Protection Policy 2018 c. Data Protection Breach Regulations 2018 d. Mobile Device Security Regulations 2018 e. -

Laws and List of the Members of the Medical Society of Edinburgh

LAWS AND LIST OF THE MEMBERS OF THE MEDICAL SOCIETY o I? EDINBURGH. Jnfiltuted 1737. Incorporated by Royal Charter i 778. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY MUNDELL b* SOiV FOR THE SOCIETY, 3792. CONTENTS. Page - Chap, I. OfOrdinary Meetings - i II. — Extraordinary Meetings - -. 4 - III. — 'The Decijions of the Society 5 - - IV. — Ordinary Members 8 V. — Extraordinary Members - m 9 — VI, Correfponding Members - 10 - - VII. — Honorary Members IX — VIII. Prejidents - - - 12 - XI. — The Treafurer - iG - X. —- I’he Secretary and Librarian 17 - - XI, — Vifitors - 2t XII. — Providing Subjects for Dijfertations 24 - XIII. — The Delivery of Dijfertations 27 ~ XIV* — The Circulation of Minutes and Differ tations • XV. — The Reading of Dijfertations - 31 - - - XVI. — The Library 32 - - XVII. — Committees - 35 - - XIX. — Penalties - 41 - XX. — T’he Colledion of Money 41 - - - XXL — Diplomas 44 - - - XXII. — Expulfon 47 XXIII. — New Laws - - 49 Order of the Proceedings of the Society at Ordinary - - - Meetings - 50 - Private Btfinefs - • ib. Private IV C O' N T E N T S. Page - - public Bujinefs - - 51 - - Lift of the Medical Society - 55 - Lift of Honorary Members - 95 Lift ofAnnual Prefdents - - - 103 N. B. Thofe whofe names are printed.in Italics have been ele&ed Honorary Members. Thofe to whofe names are prefixed this mark * have been Annual Prefidents# I LAWS OF THE MEDICAL SOCIETY. CHAPTER I. OF ORDINARY MEETINGS. l. The ordinary meetings of the Society fhall com- mence the lad Saturday but one of October, and be held every Saturday until twelve fets of members (hall have read their diflertations. Each ordinary meeting for private bufinefs (hall commence at fix o’clock P. -

Gabriel Jackson

Gabriel Jackson Sacred choral WorkS choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Matthew owens Gabriel Jackson choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Sacred choral WorkS Matthew owens Edinburgh Mass 5 O Sacrum Convivium [6:35] 1 Kyrie [2:55] 6 Creator of the Stars of Night [4:16] Katy Thomson treble 2 Gloria [4:56] Katy Thomson treble 7 Ane Sang of the Birth of Christ [4:13] Katy Thomson treble 3 Sanctus & Benedictus [2:20] Lewis Main & Katy Thomson trebles (Sanctus) 8 A Prayer of King Henry VI [2:54] Robert Colquhoun & Andrew Stones altos (Sanctus) 9 Preces [1:11] Simon Rendell alto (Benedictus) The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 4 Agnus Dei [4:24] 10 Psalm 112: Laudate Pueri [9:49] 11 Magnificat (Truro Service) [4:16] Oliver Boyd treble 12 Nunc Dimittis (Truro Service) [2:16] Ben Carter bass 13 Responses [5:32] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 14 Salve Regina [5:41] Katy Thomson treble 15 Dismissal [0:28] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 16 St Asaph Toccata [8:34] Total playing time [70:22] Recorded in the presence Producer: Paul Baxter All first recordings Michael Bonaventure organ (tracks 10 & 16) of the composer on 23-24 Engineers: David Strudwick, (except O Sacrum Convivium) February and 1-2 March 2004 Andrew Malkin Susan Hamilton soprano (track 10) (choir), 21 December 2004 (St Assistant Engineers: Edward Cover image: Peter Newman, The Choir of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Asaph Toccata) and 4 January Bremner, Benjamin Mills Vapour Trails (oil on canvas) 2005 (Laudate Pueri) in St 24-Bit digital editing: Session Photography: -

London Metropolitan Archives Mayor's Court

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 MAYOR'S COURT, CITY OF LONDON CLA/024 Reference Description Dates COURT ROLLS Early Mayor's court rolls CLA/024/01/01/001 Roll A 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/002 Roll B 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/003 Roll C 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/004 Roll D 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/005 Roll E 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/006 Roll F 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/007 Roll G 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/008 Roll H 1298 - 1307 1 roll CLA/024/01/01/009 Roll I 1298 - 1307 1 roll Plea and memoranda rolls CLA/024/01/02/001 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1323-1326 Former Reference: A1A CLA/024/01/02/002 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1327-1336 A sample image is available to view online via the Player and shows an llustration of a pillory (membrane 16 on Mayor's Court Plea and Memoranda Roll). To see more entries please consult the entire roll at London Metropolitan Archives. Former Reference: A1B LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 MAYOR'S COURT, CITY OF LONDON CLA/024 Reference Description Dates CLA/024/01/02/003 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1332 Former Reference: A2 CLA/024/01/02/004 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1338-1341 Former Reference: A3 CLA/024/01/02/005 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1337-1338, Former Reference: A4 1342-1345 CLA/024/01/02/006 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1337-1339, Former Reference: A5 1341-1345 CLA/024/01/02/007 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1349-1350 Former Reference: A6 CLA/024/01/02/008 Plea and Memoranda Roll 1354-1355 12 April 1355 - Names of poulterers sworn to supervise the trade in Leaderhall, Poultry and St. -

View of the Great

This dissertation has been 62—769 microfilmed exactly as received GABEL, John Butler, 1931- THE TUDOR TRANSLATIONS OF CICERO'S DE OFFICIIS. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE TUDOR TRANSLATIONS OP CICERO'S DE OFFICIIS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By John Butler Gabel, B. A., M. A., A. M. ****** The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of Ehglis7 PREFACE The purpose of this dissertation is to throw light on the sixteenth-century English translations of De Offioiis, one of Cicero’s most popular and most influential works. The dissertation first surveys the history and reputation of the Latin treatise to I600 and sketchs the lives of the English translators. It then establishes the facts of publication of the translations and identifies the Latin texts used in them. Finally it analyzes the translations themselves— their syntax, diction, and English prose style in general— against the background of the theory and prac tice of translation in their respective periods. I have examined copies of the numerous editions of the translations in the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Library of Congress, and the libraries of the Ohio State University and the University of Illinois. I have also made use of films of copies in the British Museum and the Huntington Library. I have indicated the location of the particular copies upon which the bibliographical descrip tions in Chapter 3 are based. -

Musica Britannica

T69 (2021) MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens c.1750 Stainer & Bell Ltd, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 ILS England Telephone : +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] www.stainer.co.uk MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Musica Britannica, founded in 1951 as a national record of the British contribution to music, is today recognised as one of the world’s outstanding library collections, with an unrivalled range and authority making it an indispensable resource both for performers and scholars. This catalogue provides a full listing of volumes with a brief description of contents. Full lists of contents can be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Where performing material is shown as available for rental full details are given in our Rental Catalogue (T66) which may be obtained by contacting our Hire Library Manager. This catalogue is also available online at www.stainer.co.uk. Many of the Chamber Music volumes have performing parts available separately and you will find these listed in the section at the end of this catalogue. This section also lists other offprints and popular performing editions available for sale. If you do not see what you require listed in this section we can also offer authorised photocopies of any individual items published in the series through our ‘Made- to-Order’ service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. In addition, choirs now have the opportunity to purchase individual choral titles from selected volumes of the series as Adobe Acrobat PDF files via the Stainer & Bell website. -

Hampshire Bibliography

127 A SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO HAMPSHIRE BIBLIOGRAPHY. BY REV. R. G. DAVIS. The Bibliography of Hampshire was first attempted by the Rev. Sir W. H. Cope, Bart., who compiled and printed " A LIST OF BOOKS RELATING TO HAMPSHIRE, IN THE LIBRARY AT BRAMSHILL." 8VO. 1879. (Not Published.) The entire collection, with many volumes of Hampshire Views and Illustrations, was bequeathed by Sir W. Cope to the Hartley Institution, mainly through the influence of the late Mr. T. W. Shore, and' on the death of the donor in 1892 was removed to Southampton. The List compiled by the original owner being " privately printed' became very rare, and was necessarily incomplete. In 1891 a much fuller and more accurate Bibliography was published with the following title:—" BIBLIOTHECA HANTONIENSIS, a List of Books relating, to Hampshire, including Magazine References, &c, &c, by H. M. Gilbert and the Rev. G. N. Godwin, with a List of Hampshire Newspapers, by F. E. Edwards. Southampton. 1891. The List given in the above publication was considerably augmented by a SUPPLEMENTARY HAMPSHIRE BIBLIOGRAPHY, compiled by the Rev. Sumner Wilson, Rector of Preston Candover, printed in the PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HAMPSHIRE FIELD CLUB. Vol. III., p. 303. A further addition to the subject is here offered with a view to rendering the Bibliography of Hants as complete as possible. Publications referring to the Isle of Wight are not comprised in this List. 128 FIRST PORTION.—Letters A to K. ACT for widening the roads from the end of Stanbridge Lane, near a barn in the Parish of Romsey. -

The College and Canons of St Stephen's, Westminster, 1348

The College and Canons of St Stephen’s, Westminster, 1348 - 1548 Volume I of II Elizabeth Biggs PhD University of York History October 2016 Abstract This thesis is concerned with the college founded by Edward III in his principal palace of Westminster in 1348 and dissolved by Edward VI in 1548 in order to examine issues of royal patronage, the relationships of the Church to the Crown, and institutional networks across the later Middle Ages. As no internal archive survives from St Stephen’s College, this thesis depends on comparison with and reconstruction from royal records and the archives of other institutions, including those of its sister college, St George’s, Windsor. In so doing, it has two main aims: to place St Stephen’s College back into its place at the heart of Westminster’s political, religious and administrative life; and to develop a method for institutional history that is concerned more with connections than solely with the internal workings of a single institution. As there has been no full scholarly study of St Stephen’s College, this thesis provides a complete institutional history of the college from foundation to dissolution before turning to thematic consideration of its place in royal administration, music and worship, and the manor of Westminster. The circumstances and processes surrounding its foundation are compared with other such colleges to understand the multiple agencies that formed St Stephen’s, including that of the canons themselves. Kings and their relatives used St Stephen’s for their private worship and as a site of visible royal piety. -

The Life and Amazing Times of William Waynflete

The Life and Amazing Times of William Waynflete by Anna Withers Among the occupants of the chantry chapels of Winchester Cathedral, William Waynflete impresses by reason of his longevity, living as he did until the age of 87 (if he was born in 1399) and under the reigns of eight kings, four of whom died by violence. To preserve life and high office during the turbulent loyalties and internecine feuds of the Wars of the Roses was a feat indeed: one might suppose that Waynflete achieved it by studious avoidance of political prominence and controversy, but in fact nothing could be further from the truth. Fig 1 Effigy of William of Wayneflete in Winchester Cathedral Photo: Julie Adams He was born in Wainfleet in Lincolnshire, possibly as early as 1395. His family name was Patten, or sometimes Barbour. Henry Beaufort had become Bishop of Lincoln in 1398, and it has been suggested that he assisted the young William to study at Winchester College and then at New College, Oxford. However, there is no contemporary evidence that he studied there or indeed attended Oxford at all, other than a letter written to him in later life by the Chancellor of the University, describing Oxford as the “mother who brought [Waynflete] forth into the light of knowledge”. He took orders as an acolyte in 1420 in the name of William Barbour, becoming a subdeacon and then deacon (this time as William Barbour, otherwise Waynflete of Spalding) in 1421, finally being ordained priest in 1426. He seems to have been marked out early as a young man of ability and potential. -

Copyright by Donna Elaine Hobbs 2012

Copyright by Donna Elaine Hobbs 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Donna Elaine Hobbs Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Telling Tales out of School: Schoolbooks, Audiences, and the Production of Vernacular Literature in Late Medieval England Committee: Marjorie Curry Woods, Co-Supervisor Elizabeth D. Scala, Co-Supervisor Mary E. Blockley Timothy J. Moore Wayne A. Rebhorn, Jr. Wayne Lesser Telling Tales out of School: Schoolbooks, Audiences, and the Production of Vernacular Literature in Late Medieval England by Donna Elaine Hobbs, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2012 In fond remembrance of past joys Roberta LaRue Jacobe Robert Leo Hartwiger Garnet LaRue Hartwiger and in celebration of present delights Elena LaRue Hobbs Cameron William Hobbs Adeliza LaRue Hobbs Acknowledgments While “Telling Tales out of School” recognizes that the books encountered in the classroom influence adult compositions, the completion of this project demonstrates that the relationships forged both in and out of school become an intrinsic part of one’s writing as well. The encouragement and kindness of my teachers, friends, and family have left a deep impression on my life and work, and for them I am grateful. My supervisors have been supportive of my studies since my first days at the University of Texas at Austin. Marjorie Curry Woods shared with me not only her passion for medieval education but also her unwavering belief in the value of my insights. -

An Eton Bibliography

r t "1 ^J^JJ^-A (^7^ ^KJL^ AN ETON BIBLIOGRAPHY By L. V. HARCOURT ARTHUR L. HUMPHREYS, 187 PICCADILLY, LONDON 1902 ^^J3 //J /Joe PREFA CE. ^HIS new edition of Eton Bibliogr'aphy, like its predecessors, is mainly compiled from the catalogue of my own collection of ''' Etoniana'^ {destined ultimately for the School Library). I have added the titles of those hooks of which I know, but do not possess copies: these I have distinguished with an asterisk (*) in the hope that I may hear of copies of them for sale or exchange. I have endeavoured as far as possible—and with much success —to discover and record the names of the authors of anonymous books and pamphlets and of the editors of the ephemeral School Magazines, but I have felt bound, in printing this Bibliography, in many cases to respect their anonymity. There are, however, many anonymous authors still to be identified, and I shall gratefully receive any information on this or other subjects by way of addenda to or corrigenda of the Bibliography. I have intentionally omitted all School text-books from the collection. L. V. HARCOURT, 14 Berkeley Square, London, W, iv»21'1f>"?6 AN ETON BIBLIOGRAPHY 1560. Three Sermons preached at Eaton Colledge. By Roger Hutchinson. 1552. Pp. 110. Sm. 16mo. John Day, Aldersgate, London. 1567. Gualteri Haddoni, Legum doctoris, S. Reginae Elizabethae a supplicium libellis, lucubrationes passim collectae et editae. Et Poemata. Studio et labore Thomae Hatcheri Cantabri- gierisis. 2 vols. Vol. I., pp. I., viii., 350; II., ii., 141. Sm. post 8vo. -

Missionaries, Modernity and the Moving Image

Missionaries, modernity and the moving image: re-presenting the Melanesian Other to Christian communities in the West between the World Wars Stella Ramage A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington February 2015 ii Contents Abstract . v List of abbreviations . vi List of illustrations . vii Acknowledgements . xi Prologue . 1 Introduction . 3 PART ONE – Strange Bedfellows: Missionaries And Travelogue-Adventurers Chapter One: Facilitation: Missionaries Behind the Scenes . 27 . Chapter Two: Commissioning: Missionaries Engage Help . 77 Chapter Three: Collaboration The Thoroughly Modern Missionary And The American Movie-Maker . 121 PART TWO – Alone at last? Missionaries Roll Their Own Chapter Four: Seventh-Day Adventist Case Study: Cannibals and Christians . 161 Chapter Five: Roman Catholic Case Study: Saints and Savages . 205 Conclusion . 259 Postscript . 277 Bibliography . 279 iii iv Abstract This thesis considers conflicting representational strategies used by Christian missionaries in displaying Melanesian people to white audiences in the West with particular reference to films made during the period of colonial modernity between 1917 and 1935. Most scholarly work on Christian mission in the Pacific has focussed on the nineteenth century and on the effect of Christianisation on indigenous populations, rather than on the effect of mission propaganda on Western communities. This thesis repositions mission propaganda as an important alternative source of visual imagery of the Melanesian ‘Other’ available to white popular audiences. Within a broader commercial market that commodified Western notions of Melanesian ‘savagery’ via illustrated travelogue magazines and commercial multi-media shows, missionaries trod an uneasy knife-edge in how they transmitted indigenous imagery and mediated cultural difference for white consumers.