Missionaries, Modernity and the Moving Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lonely Island

The Lonely Island By R. M. Ballantyne The Lonely Island Chapter One. The Refuge of the Mutineers. The Mutiny. On a profoundly calm and most beautiful evening towards the end of the last century, a ship lay becalmed on the fair bosom of the Pacific Ocean. Although there was nothing piratical in the aspect of the shipif we except her gunsa few of the men who formed her crew might have been easily mistaken for roving buccaneers. There was a certain swagger in the gait of some, and a sulky defiance on the brow of others, which told powerfully of discontent from some cause or other, and suggested the idea that the peaceful aspect of the sleeping sea was by no means reflected in the breasts of the men. They were all British seamen, but displayed at that time none of the wellknown hearty offhand rollicking characteristics of the Jacktar. It is natural for man to rejoice in sunshine. His sympathy with cats in this respect is profound and universal. Not less deep and wide is his discord with the moles and bats. Nevertheless, there was scarcely a man on board of that ship on the evening in question who vouchsafed even a passing glance at a sunset which was marked by unwonted splendour. The vessel slowly rose and sank on a scarce perceptible oceanswell in the centre of a great circular field of liquid glass, on whose undulations the sun gleamed in dazzling flashes, and in whose depths were reflected the fantastic forms, snowy lights, and pearly shadows of cloudland. -

(Mutiny on the Bounty, 1935) És Una Pel·Lícula Norda

La legendària rebel·lió a bord de la Bounty La tragèdia de la Bounty (Mutiny on the Bounty , 1935) és una pel·lícula nordamericana, dirigida per Frank Lloyd, i interpretada per Clarck Gable i Charles Laughton, que relata la història de l'amotinament dels mariners de la Bounty . El 28 d'abril de 1789, 31 dels 46 homes del veler de l'armada britànica Bounty s'amotinaren. L'oficial Fletcher Christian encapçalà l'amotinament contra el comandant de la nau, el tinent William Bligh, un marí amb experiència, que havia acompanyat Cook en el seu tercer viatge al Pacífic. La nau havia marxat a la Polinèsia per tal d'arreplegar especímens de l'arbre del pa, per tal de dur-los al Carib, perquè els seus fruits, rics en glúcids, serviren d'aliment als esclaus. El 26 d'octubre de 1788 ja havien carregat 1015 exemplars de l'arbre. En començar el viatge de tornada es va produir l'amotinament i els mariners llançaren els arbres al mar. Bligh i 18 homes foren abandonats en un bot. En 1790, després de 6.000 km de navegació heròica, arribaren a Gran Bretanya. L'armada britànica envià un vaixell per reprimir el motí, el Pandora , comandat per Erward Edwards. Va matar 4 amotinats. Per haver perdut la nau, Bligh va patir un consell de guerra. En 1804 fou governador de Nova Gal·les del Sud (Austràlia) i la seua repressió del comerç de rom provocà una revolta. L'única colònia britànica que queda en el Pacífic són les illes Pitcairn. Els seus 50 habitants (dades 2010) viuen en la major de les illes, de 47 km 2. -

The Canoe Is the People LEARNER's TEXT

The Canoe Is The People LEARNER’S TEXT United Nations Local and Indigenous Educational, Scientific and Knowledge Systems Cultural Organization Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 1 14/11/2013 11:28 The Canoe Is the People educational Resource Pack: Learner’s Text The Resource Pack also includes: Teacher’s Manual, CD–ROM and Poster. Produced by the Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, UNESCO www.unesco.org/links Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ©2013 UNESCO All rights reserved The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Coordinated by Douglas Nakashima, Head, LINKS Programme, UNESCO Author Gillian O’Connell Printed by UNESCO Printed in France Contact: Douglas Nakashima LINKS Programme UNESCO [email protected] 2 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 2 14/11/2013 11:28 contents learner’s SECTIONTEXT 3 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 3 14/11/2013 11:28 Acknowledgements The Canoe Is the People Resource Pack has benefited from the collaborative efforts of a large number of people and institutions who have each contributed to shaping the final product. -

Postal Stamp Auction Tuesday 16 February 2021 5 31

POSTAL STAMP AUCTION TUESDAY 16 FEBRUARY 2021 5 31 2835 2091 2854 2945 2094 3469 MOWBRAY COLLECTABLES, PRIVATE BAG 63000, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND 6140 675 676 679 680 681 682 684 685 687 688 690 691 692 693 694 695 699 703 701 705 706 710 712 713 716 738 741 743 745 746 747 756 764 765 817 791 837 838 875 842 ex 843 ex 850 841 878 899 896 911 885 904 916 917 - image reduced in size 905 POSTAL AUCTION 531 Closes: Tuesday 16th February 2021 912 929 918 932 INDEX OF LOTS 1 - 373 Collections & Accumulations 374 - 420 Collectables 421 - 521 Thematics 522 - 535 Accessories 536 - 538 Catalogues 539 - 563 Literature 564 - 626 New Zealand - Postal History 933 938 941 944 976 627 - 674 - Postal Stationery 675 - 1317 - Definitives 1318 - 1343 - Airmail 1344 - 1541 - Commemoratives 1542 - 1631 - Health 1632 - 1824 - Officials 1825 - 1876 - Life Insurance 977 982 985 1877 - 1946 - Postal Fiscals 1947 - 1966 - Booklets 1967 - 2088 - Other 2089 - 2187 - Revenues 2188 - 2222 - Cinderellas 2223 - 2295 Polar 2296 - 2330 Flight Covers 2331 - 2558 Australia 991 ex 1002 1006 1015 1027 1198 2559 - 2826 Pacific Islands 2827 - 2941 Great Britain 2942 - 3380 British Commonwealth 3381 - 3883 Foreign IMPORTANT INFORMATION: - You can bid by mail, phone, fax, email or via our website - see contact details below. - For enquiries on any lots, contact our office as above. - Lots are listed on a simplified basis unless otherwise stated. 996 1043 1046 - Stamps illustrated in colour may not be exactly true to shade. - Bids under 2/3rds of estimate are generally not considered. -

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea

Captain Bligh's Second Voyage to the South Sea By Ida Lee Captain Bligh's Second Voyage To The South Sea CHAPTER I. THE SHIPS LEAVE ENGLAND. On Wednesday, August 3rd, 1791, Captain Bligh left England for the second time in search of the breadfruit. The "Providence" and the "Assistant" sailed from Spithead in fine weather, the wind being fair and the sea calm. As they passed down the Channel the Portland Lights were visible on the 4th, and on the following day the land about the Start. Here an English frigate standing after them proved to be H.M.S. "Winchelsea" bound for Plymouth, and those on board the "Providence" and "Assistant" sent off their last shore letters by the King's ship. A strange sail was sighted on the 9th which soon afterwards hoisted Dutch colours, and on the loth a Swedish brig passed them on her way from Alicante to Gothenburg. Black clouds hung above the horizon throughout the next day threatening a storm which burst over the ships on the 12th, with thunder and very vivid lightning. When it had abated a spell of fine weather set in and good progress was made by both vessels. Another ship was seen on the 15th, and after the "Providence" had fired a gun to bring her to, was found to be a Portuguese schooner making for Cork. On this day "to encourage the people to be alert in executing their duty and to keep them in good health," Captain Bligh ordered them "to keep three watches, but the master himself to keep none so as to be ready for all calls". -

The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University: a Selected, Annotated Catalogue (1994)

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Special Collections Bibliographies University Special Collections 1994 The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University: A Selected, Annotated Catalogue (1994) Gisela S. Terrell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib Part of the Other History Commons Recommended Citation Terrell, Gisela S., "The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University: A Selected, Annotated Catalogue (1994)" (1994). Special Collections Bibliographies. 5. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/scbib/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Special Collections at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections Bibliographies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WILLIAM F. CHARTERS SOUTH SEAS COLLECTION The Irwin Library Butler University Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/williamfchartersOOgise The William F. Charters South Seas Collection at Butler University A Selected, Annotated Catalogue By Gisela Schluter Terrell With an Introduction By George W. Geib 1994 Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University Indianapolis, Indiana ©1994 Gisela Schluter Terrell 650 copies printed oo recycled paper Printed on acid-free, (J) Rare Books & Special Collections Irwin Library Butler University 4600 Sunset Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana 46208 317/283-9265 Produced by Butler University Publications Dedicated to Josiah Q. Bennett (Bookman) and Edwin J. Goss (Bibliophile) From 1972 to 1979, 1 worked as cataloguer at The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. Much of what I know today about the history of books and printing was taught to me by Josiah Q. -

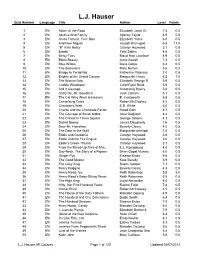

AR Quizzes for L.J. Hauser

L.J. Hauser Quiz Number Language Title Author Level Points 1 EN Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gr 7.4 0.5 2 EN All-of-a-Kind Family Sydney Taylor 4.9 0.5 3 EN Amos Fortune, Free Man Elizabeth Yates 6.0 0.5 4 EN And Now Miguel Joseph Krumgold 6.8 11.0 5 EN "B" is for Betsy Carolyn Haywood 3.1 0.5 6 EN Bambi Felix Salten 4.6 0.5 7 EN Betsy-Tacy Maud Hart Lovelace 4.9 0.5 8 EN Black Beauty Anna Sewell 7.3 0.5 9 EN Blue Willow Doris Gates 6.4 0.5 10 EN The Borrowers Mary Norton 5.6 0.5 11 EN Bridge to Terabithia Katherine Paterson 7.0 0.5 12 EN Brighty of the Grand Canyon Marguerite Henry 6.2 7.0 13 EN The Bronze Bow Elizabeth George S 5.9 0.5 14 EN Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink 5.6 0.5 15 EN Call It Courage Armstrong Sperry 5.0 0.5 16 EN Carry On, Mr. Bowditch Jean Latham 5.1 0.5 17 EN The Cat Who Went to Heaven E. Coatsworth 5.8 0.5 18 EN Centerburg Tales Robert McCloskey 5.2 0.5 19 EN Charlotte's Web E.B. White 6.0 0.5 20 EN Charlie and the Chocolate Factor Roald Dahl 6.7 0.5 21 EN The Courage of Sarah Noble Alice Dalgliesh 4.2 0.5 22 EN The Cricket in Times Square George Selden 4.3 0.5 23 EN Daniel Boone James Daugherty 7.6 0.5 24 EN Dear Mr. -

Adult Trade January-June 2018

BLOOMSBURY January – June 2018 NEW TITLES January – June 2018 2 Original Fiction 12 Paperback Fiction 26 Crime, Thriller & Mystery 32 Paperback Crime, Thriller & Mystery 34 Original Non-Fiction 68 Food 78 Wellbeing 83 Popular Science 87 Nature Writing & Outdoors 92 Religion 93 Sport 99 Business 102 Maritime 104 Paperback Non-fiction 128 Bloomsbury Contact List & International Sales 131 Social Media Contacts 132 Index export information TPB Trade Paperback PAPERBACK B format paperback (dimensions 198 mm x 129 mm) Peach Emma Glass Introducing a visionary new literary voice – a novel as poetic as it is playful, as bold as it is strangely beautiful omething has happened to Peach. Blood runs down her legs Sand the scent of charred meat lingers on her flesh. It hurts to walk but she staggers home to parents that don’t seem to notice. They can’t keep their hands off each other and, besides, they have a new infant, sweet and wobbly as a jelly baby. Peach must patch herself up alone so she can go to college and see her boyfriend, Green. But sleeping is hard when she is haunted by the gaping memory of a mouth, and working is hard when burning sausage fat fills her nostrils, and eating is impossible when her stomach is swollen tight as a drum. In this dazzling debut, Emma Glass articulates the unspeakable with breathtaking clarity and verve. Intensely physical, with rhythmic, visceral prose, Peach marks the arrival of a ground- breaking new talent. 11 JANUARY 2018 HARDBACK • 9781408886694 • £12.99 ‘An immensely talented young writer . Her fearlessness renews EBOOK • 9781408886670 • £10.99 one’s faith in the power of literature’ ANZ PUB DATE 01 FEBRUARY 2018 George Saunders HARDBACK • AUS $24.99 • NZ $26.99 TERRITORY: WO ‘You'll be unable to put it down until the very last sentence’ TRANSLATION RIGHTS: BLOOMSBURY Kamila Shamsie ‘Peach is a work of genius. -

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography

Bounty Saga Articles Bibliography By Gary Shearer, Curator, Pitcairn Islands Study Center "1848 Watercolours." Pitcairn Log 9 (June 1982): 10-11. Illus in b&w. "400 Visitors Join 50 Members." Australasian Record 88 (July 30,1983): 10. "Accident Off Pitcairn." Australasian Record 65 (June 5,1961): 3. Letter from Mrs. Don Davies. Adams, Alan. "The Adams Family: In The Wake of the Bounty." The UK Log Number 22 (July 2001): 16-18. Illus. Adams, Else Jemima (Obituary). Australasian Record 77 (October 22,1973): 14. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, Gilbert Brightman (Obituary). Australasian Record 32 (October 22,1928): 7. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, Hager (Obituary). Australasian Record 26 (April 17,1922): 5. Died on Norfolk Island. Adams, M. and M. R. "News From Pitcairn." Australasian Record 19 (July 12,1915): 5-6. Adams, M. R. "A Long Isolation Broken." Australasian Record 21 (June 4,1917): 2. Photo of "The Messenger," built on Pitcairn Island. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (April 30,1956): 2. Illus. Story of Miriam and her husband who labored on Pitcairn beginning in December 1911 or a little later. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 7,1956): 2-3. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 14,1956): 2-3. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 21,1956): 2. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (May 28,1956): 2. Illus. Adams, Miriam. "By Faith Alone." Australasian Record 60 (June 4,1956): 2. Adams, Miriam. "Letter From Pitcairn Island." Review & Herald 91 (Harvest Ingathering Number,1914): 24-25. -

Download Conference Book

目次 Contents 會議介紹與歡迎詞 Conference Introduction and Welcome Remarks 1 會議議程 Agenda 3 專題演講 Keynote Speeches 13 會議論文摘要 Presentation Abstracts 19 December 3 21 Roundtable: Path (conference theme) 21 Engagements, Narratives and Impacts of WWII 22 Comparative Colonialism: Colonial Regimes Across the Pacific 26 Crossing Divides: Movements of People and Objects in Contemporary Taiwan 29 Pan‐Pacific Indigenous Resource Management: Part 1 33 Genres of Articulation: Cultural Nationalism and Beyond 37 Colonial Encounters as Contact Zone 40 Micronesia History & Identity 42 Reconsidering Asian Diasporas in the Pacific 45 Outreach Teaching & Appropriate Education Models for Pacific Communities 48 Climate Change, Disasters & Pacific Agency 52 Contestations and Negotiations of History and Landscape 56 Studying History Through Music 58 December 5 61 Visualization and Exhibition of Nature and Culture in the Pacific 61 Pan‐Pacific Indigenous Resource Management: Part 2 64 Methodologies & Themes in Reconstructing Hidden Cultural Histories 68 The Rise and Fall of Denominations 71 Pacific Transnationalism: Welcome, Rejection, Entanglement: Part 1 74 Special Event: Exchanging Reflections on Ethnographic Filming 77 Rethinking Relations to Land 78 Pacific Transnationalism: Welcome, Rejection, Entanglement: Part 2 82 ‘Swift Injustice’: Punitive Expeditions in East Asia and the Western Pacific: Part 1 85 Fluid Frontiers: Oceania & Asia in Historical Perspectice: Part 1 88 Iconicity, Performance & Consumption of Culture & Ethnicity 91 Historicizing Gender and Power -

Download a PDF of the Catalogue

POSTAL STAMP AUCTION TUESDAY 15 JUNE 2021 535 639 682 964 1397 1398 MOWBRAY COLLECTABLES, PRIVATE BAG 63000, WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND 6140 ex 75 626 627 630 635 636 637 644 647 649 657 643 671 681 699 704 754 ex 760 752 756 795 813 824 825 827 830 838 839 ex 850 866 879 913 914 915 916 932 1032 1050 1064 1093 1117 ex 1169 1134 1151 1224 1227 1240 1241 1245 1260 ex 1293 1320 POSTAL AUCTION 535 th ex 1377 Closes: Tuesday 15 June 2021 INDEX OF LOTS 1 - 289 Collections & Accumulations 290 - 325 Collectables 326 - 475 Thematics ex 1323 ex 1338 476 - 488 Accessories 489 - 513 Literature ex 1388 514 - 582 New Zealand - Postal History 583 - 625 - Postal Stationery 626 - 1187 - Definitives 1188 - 1212 - Airmail 1213 - 1438 - Commemoratives 1439 - 1531 - Health 1532 - 1707 - Officials 1708 - 1750 - Life Insurance 1751 - 1813 - Postal Fiscals ex 1463 1527 1752 1533 1570 1814 - 1831 - Booklets 1832 - 1960 - Other 1961 - 2085 - Revenues 2086 - 2123 - Cinderellas 2124 - 2205 Polar 2206 - 2245 Flight Covers 2246 - 2395 Australia 2396 - 2697 Pacific Islands 1589 1777 2698 - 2817 Great Britain 2818 - 3354 British Commonwealth ex 1532 ex 1536 1550 3355 - 3862 Foreign IMPORTANT INFORMATION: - You can bid by mail, phone, fax, email or via our website - see contact details below. - For enquiries on any lots, contact our office as above. - Lots are listed on a simplified basis unless otherwise stated. - Stamps illustrated in colour may not be exactly true to shade. - Bids under 2/3rds of estimate are generally not considered. - NZ Bidders: GST of 15% will be added to successful bids. -

Tcp a 41 Pg 1

www.thecoastalpassage.com SV Ise Pearl Sailing in Pioneer Bay, Whitsundays Photo courtesy of Whitsunday Traditional Boat Club Australia Day at Tin Can Bay! www.thecoastalpassage.com Julie Hartwig photos mailto:[email protected] Reflections By Alan Lucas, SY Soleares Telstra Overheads Hating Telstra is a national sport, the electricity lines but without new signage genesis of which probably lies in its regarding their lower height. The worst privatisation a couple of decades ago. example was a cable so low that I could Then, as always, public outcry was totally almost reach it by standing on the dinghy's ignored by governments of the day hell thwart, yet it was still signed for the height bent on selling off our country's of the original electricity cables of over ten infrastructure. And as for Telecom, as metres! In one river alone we found six Telstra was once known, the question was such breaches of the law. why sell a publicly-owned entity that was leading in the world of communication If we, the common people, bring down an technology, was making a profit, employed overhead cable with our masts, we are thousands of technicians and, most fined thousands of dollars (one mate importantly, was obliged to be answerable copped an $11,000 fine), but optic cables, Alan to the public, not some imported CEO who apparently, can be flung across rivers sacked thousands, scrapped half our public without a statement of their lower height. me; I'm sorry but I'll have to put you on hold That was it: I gave up.