Optimizing Video for Learning V4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21-0706-MEDALLIONS-Call for Entry Brochure.Pdf

ENTERYOURFINEST 2021 MEDALLIONENTER YOUR ENTERYOURAWARDS FINEST ENTERYOUR ENTERYOURFINEST ENTERYOURFINEST ENTERYOURFINEST ENTERYOURFINEST ENTERYOURFINEST ENTER YOUR PASSION ENTRY DETAILS WHO CAN ENTER The creative effort/concept must 2021 have originated from a community medallion or technical college or district or AWARDS state governing organization for two-year colleges. Entries may not be submitted through an ad YOu’VE DONE GReaT WORK. YOu’VE PUT IN EXTRA HOURS. agency; make submissions through a college, district or state govern- YOU DESERVE TO BE CELEBRATED FOR yoUR ACCOMPLISHMENTS. ing association only. In a time when creativity has been stretched to the limits, it’s WHAT TO ENTER important to take the time to reflect on your relentless pursuit of Entries must have been published, broadcast, displayed and used excellence. Show everyone the inspirational work you and your between July 1, 2020 and team have produced during one of the most challenging years June 30, 2021. in recent memory. Entries must be new designs or publications in the entry year; those that represent previously SPONSORED BY the National Council for RECOGNIZED AS the leading professional submitted work with minor Marketing & Public Relations (NCMPR), development organization for two-year modifications will be disqualified. the Medallion Awards recognize outstanding college communicators, NCMPR provides achievement in design and communication regional and national conferences, Entries must be original, creative at community and technical colleges webinars, a leadership institute, relevant work WITHOUT THE USE OF in each of seven districts. It’s the only information on emerging marketing TEMPLATES customized for regional competition of its kind that honors and PR trends, and connections to a individual college use. -

The Clash of Two Images China's Media

THE CLASH OF TWO IMAGES CHINA’S MEDIA OFFENSIVE IN THE UNITED STATES by FAN BU MAY 2013 Committee Fritz Cropp, Chair Clyde Bentley Wesley Pippert ii THE CLASH OF TWO IMAGES CHINA’S MEDIA OFFENSIVE IN THE UNITED STATES Fan Bu Fritz Cropp, Project Supervisor ABSTRACT At a time when most Western newspaper and broadcasting companies are scaling back, China's state-run media organizations are fast growing and reaching into every corner of the world, especially in North America and Africa. The $7 billion campaign to expand China’s soft power has significantly increased its media presence. But are these media offensive efforts effective? This paper analyzes the current state of the media expansion, the motivation behind it, the obstacles, suggestions and the outlook in the decades to come. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………...……………………….ii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................1 Goals of the Study 2. WEEKLY FIELD NOTES………………………………………………………..4 3. EVALUATION…………………………………………………………………..35 4. PHYSICAL EVIDENCE OF WORK……………………………………………39 5. ANALYSIS COMPONENT……………………………………………………..42 REFERENCES…………………………………………………………………………..53 APPENDIX 1. PROFESSIONAL PROJECT PROPOSAL………………………...……………55 2. QUERY LETTER..................................................................................................66 1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION Growing up in Beijing, I was one of hundreds of millions who watched the China Central TV prime time newscast each night at 7. But I never realized how biased the programs were until I traveled back home recently after studying and working in journalism in the United States for five years. In the half-hour show, international news normally takes 5 to 10 minutes, most of which report on negative news around the world, such as riots in the Middle East or the economic crisis in Europe. -

Morrison Announces Resignation As A.D. Fire Marshall Confident About

Dmlv Nexus Volume 69, No. 105 Wednesday, April 5, 1989_______________________ University of California, Santa Barbara One Section, 16 Pages Devereaux Morrison Announces Operating Resignation as A.D. had with players.... To have a License in San Jose State Head chance at this stage of my life to go back to that is something I Coaching Offer Too can’t say no to. I’ve had some opportunities before this, but this Jeopardy Good to Let Pass By, one made sense.” Immediate impacts from Signs Four-Year Deal Morrison’s decision include questions regarding morale I.V. School Tightens within the Gaucho sports circle, By Scott Lawrence especially by coaches who say Security Procedures Staff Writer Morrison had made great strides in terms of personnel fervor and White Investigations UCSB Athletic Director Stan sense of purpose. Morrison resigned Tuesday to Reaction to Morrison’s an by State Continues accept the head basketball nouncement was consistent coaching position at San Jose among the coaches, who stood State, he announced at a Tuesday stunned inside the Events Cen morning press conference. ter’s Founder’s Room while By Adam M oss Morrison, a former head coach Morrison gave a 45-minute ad Staff Writer at Pacific and USC, will replace dress on his decision and on the Bill Berry, who was fired last state of Gaucho athletics. Under the looming threat of month following a season under “I’ve been here 13 years,” losing its license, the Devereux fire that began when 10 Spartan Head Women’s Volleyball Coach School in Isla Vista volunteered to players walked off the squad on Kathy Gregory said, “and I’d like increase security and tighten its Jan. -

Rikanischer Youtube-Kanäle

BACHELORARBEIT Frau Melanie Beier Konzeption und Entwicklung eines kostenlosen Bildungs- kanals nach dem Vorbild ame- rikanischer YouTube-Kanäle 2014 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Konzeption und Entwicklung eines kostenlosen Bildungs- kanals nach dem Vorbild ame- rikanischer YouTube-Kanäle Autor/in: Frau Melanie Beier Studiengang: Film und Fernsehen (Regie) Seminargruppe: FF11wR1-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Robert J. Wierzbicki Zweitprüfer: Constantin Lieb, Master of Arts Einreichung: Berlin, 24. Juni 2014 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS Conception and development of a free educational channel author: Ms. Melanie Beier course of studies: Film and Television (Directing) seminar group: FF11wR1-B first examiner: Prof. Dr.-Eng. Robert J. Wierzbicki second examiner: Constantin Lieb, Master of Arts submission: Berlin, 24th of June 2014 Bibliografische Angaben Beier, Melanie: Konzeption und Entwicklung eines kostenlosen Bildungskanals nach dem Vorbild amerikanischer YouTube-Kanäle. Conception and development of a free educational channel. 130 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2014 Abstract Diese Bachelorarbeit befasst sich mit der Konzeption und Entwicklung kostenloser Bil- dungskanäle. Sie beinhaltet einen Überblick über die Charakteristiken des webbasier- ten Lernens und die ökonomischen und sozialen Gegebenheiten des Web 2.0, eine Marktanalyse des deutsch- und englischsprachigen Online-Bildungsmarktes auf YouTube sowie eine Übersicht der Finanzierungs- und Gewinnmöglichkeiten -

Festival Daily

tuesday 2. 7. 2019 05 free festival kviff’s main media partner Inside Main Competition: The Father and Half-Sister 02 daily Road trip Over the Hills 03 East of the West: tense connections 04 special edition of Právo Photo: KVIFF Photo: According to the film’s director, Hutchence had a way to cut through Melbourne punk scene bullshit. Beyond the rock star Lowenstein says in making the fi lm he gained some insight into his old friend’s character because he would show one side of himself Trapped in the 80s to his male friends that relied on having a good time, his more pub- lic persona. “He would always give Mystify: Michael Hutchence reveals the complicated fi gure behind the you a taste of what it was like to be a rock star,” he says. “But you never mythical INXS frontman really sat down and had big discus- sions about himself.” The film offered another, more In his documentary on the magnetic, enigmatic and ultimately tragic frontman for 80 s megastars INXS, Michael intimate view of the singer by the Hutchence, director Richard Lowenstein – who arrived in Karlovy Vary for the fi lm’s European premiere – plunges degree to which the perspective on him is female - with deeply the viewer completely into the singer’s life and times by only using footage from the past, without relying on talking revealing interviews from mostly heads. ex-girlfriends such as Michele Bennett, Kylie Minogue and Helena Christensen, as well as by Michael Stein personal footage of Hutchence? likes of Nick Cave and Th e Birthday out to a beach in Queensland and their US tour manager Martha It turns out he just had to walk Party had emerged, another uni- was immediately disarmed by the Troup. -

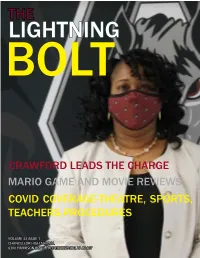

Lightning Bolt

THE LIGHTNING BOLT CRAWFORD LEADS THE CHARGE MARIO GAME AND MOVIE REVIEWS COVID COVERAGE-THEATRE, SPORTS, TEACHERS,PROCEDURES VOLUME 33 iSSUE 1 CHANCELLOR HIGH SCHOOL 6300 HARRISON ROAD, FREDERICKSBURG, VA 22407 1 Sep/Oct 2020 RETIREMENT, RETURN TO SCHOOL, MRS. GATTIE AND CRAWFORD ADVISOR FAITH REMICK Left Mrs. Bass-Fortune is at her retirement parade on June EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 24 that was held to honor her many years at Chancellor High School. For more than three CARA SEELY hours decorated cars drove by the school, honking at Mrs. NEWS EDITOR Bass-Fortune, giving her gifts and well wishes. CARA HADDEN FEATURES EDITOR KAITLYN GARVEY SPORTS EDITOR STEPHANIE MARTINEZ & EMMA PURCELL OP-ED EDITORS Above and Left: Chancellor gets a facelift of decorated doors throughout the school. MIKAH NELSON Front Cover:New Principal Mrs. Cassandra Crawford & Back Cover: Newly Retired HAILEY PATTEN Mrs. Bass-Fortune CHARGING CORNER CHARGER FUR BABIES CONTEST MATCH THE NAME OF THE PET TO THE PICTURE AND TAKE YOUR ANSWERS TO ROOM A113 OR EMAIL LGATTIE@SPOT- SYLVANIA.K12.VA.US FOR A CHANCE TO WIN A PRIZE. HAVE A PHOTO OF YOUR FURRY FRIEND YOU WANT TO SUBMIT? EMAIL SUBMISSIONS TO [email protected]. Charger 1 Charger 2 Charger 3 Charger 4 Names to choose from. Note: There are more names than pictures! Banks, Sadie, Fenway, Bently, Spot, Bear, Prince, Thor, Sunshine, Lady Sep/Oct 2020 2 IS THERE REWARD TO THIS RISK? By Faith Remick school even for two days a many students with height- money to get our kids back Editor-In-Chief week is dangerous, and the ened behavioral needs that to school safely.” I agree. -

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues

Producers of Popular Science Web Videos – Between New Professionalism and Old Gender Issues Jesús Muñoz Morcillo1*, Klemens Czurda*, Andrea Geipel**, Caroline Y. Robertson-von Trotha* ABSTRACT: This article provides an overview of the web video production context related to science communication, based on a quantitative analysis of 190 YouTube videos. The authors explore the main characteristics and ongoing strategies of producers, focusing on three topics: professionalism, producer’s gender and age profile, and community building. In the discussion, the authors compare the quantitative results with recently published qualitative research on producers of popular science web videos. This complementary approach gives further evidence on the main characteristics of most popular science communicators on YouTube, it shows a new type of professionalism that surpasses the hitherto existing distinction between User Generated Content (UGC) and Professional Generated Content (PGC), raises gender issues, and questions the participatory culture of science communicators on YouTube. Keywords: Producers of Popular Science Web Videos, Commodification of Science, Gender in Science Communication, Community Building, Professionalism on YouTube Introduction Not very long ago YouTube was introduced as a platform for sharing videos without commodity logic. However, shortly after Google acquired YouTube in 2006, the free exchange of videos gradually shifted to an attention economy ruled by manifold and omnipresent advertising (cf. Jenkins, 2009: 120). YouTube has meanwhile become part of our everyday experience, of our “being in the world” (Merleau Ponty) with all our senses, as an active and constitutive dimension of our understanding of life, knowledge, and communication. However, because of the increasing exploitation of private data, some critical voices have arisen arguing against the production and distribution of free content and warning of the negative consequences for content quality and privacy (e.g., Keen, 2007; Welzer, 2016). -

Australia's Screen Future Is Online: Time to Support Our New Content Creators

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Cunningham, Stuart (2017) Australia’s screen future is online: time to support our new content cre- ators. The Conversation, August, pp. 1-5, 2017. [Article] This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/122374/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] License: Creative Commons: Attribution-No Derivative Works 2.5 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https:// theconversation.com/ australias-screen-future-is-online-time-to-support-our-new-content-creators-82638 Academic rigour, journalistic flair Australia’s screen future is online: time to support our new content creators August 21, 2017 5.21am AEST RackaRacka, a sketch channel on YouTube, have been called Australia’s most successful content creators. -

IFA 2020 Crisis Management Paper.Pdf

International Franchise Association Franchise Law Virtual Summit August 12-13, 2020 CRISIS MANAGEMENT IN THE ERA OF FAKE NEWS Bethany Appleby Appleby & Corcoran, LLC New Haven, Connecticut John B. Gessner Fox Rothschild LLP Dallas, Texas Kathryn M. Kotel Smoothie King Franchises, Inc. Dallas, Texas Sarah A. Walters DLA Piper LLP Dallas, Texas WEST\291447123.3 Table of Contents Page I. Introduction and Examples of PR Crises in Recent Years .................................... 1 II. Can Your Company Weather the Storm? ............................................................. 4 A. Development of a Crisis Response Plan.................................................... 6 i. The Crisis Response Team ............................................................. 6 ii. Formulating a Crisis Response Plan ............................................... 7 iii. Crisis Communication Strategies .................................................... 8 iv. Controlling Communications from Franchisees and Personnel ....... 9 v. Crisis Response Training and Mock Crisis Response Trials ......... 10 B. Considerations for Involving Franchisees ................................................ 10 III. When Crisis Happens – Run Into the Flames. .................................................... 11 A. Crisis Management Plan Execution and Parallel Paths to Resolution ..... 11 B. Stabilize Stakeholders – Owners, Franchisees and Customers .............. 13 C. Resolve Central Technical and Operational Challenges .......................... 14 D. Repair the Root -

Vlogging the Museum: Youtube As a Tool for Audience Engagement

Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2014 Committee: Kris Morrissey Scott Magelssen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Museology ©Copyright 2014 Amanda Dearolph Abstract Vlogging the Museum: YouTube as a tool for audience engagement Amanda Dearolph Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Kris Morrissey, Director Museology Each month more than a billion individual users visit YouTube watching over 6 billion hours of video, giving this platform access to more people than most cable networks. The goal of this study is to describe how museums are taking advantage of YouTube as a tool for audience engagement. Three museum YouTube channels were chosen for analysis: the San Francisco Zoo, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Field Museum of Natural History. To be included the channel had to create content specifically for YouTube and they were chosen to represent a variety of institutions. Using these three case studies this research focuses on describing the content in terms of its subject matter and alignment with the common practices of YouTube as well as analyzing the level of engagement of these channels achieved based on a series of key performance indicators. This was accomplished with a statistical and content analysis of each channels’ five most viewed videos. The research suggests that content that follows the characteristics and culture of YouTube results in a higher number of views, subscriptions, likes, and comments indicating a higher level of engagement. This also results in a more stable and consistent viewership. -

Orca.Cf.Ac.Uk/118366

This is an Open Access document downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's institutional repository: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/118366/ This is the author’s version of a work that was submitted to / accepted for publication. Citation for final published version: Smith, Daniel R. 2016. "Imagining others more complexly": celebrity and the ideology of fame among YouTube's "Nerdfighteria". Celebrity Studies 7 (3) , pp. 339-353. 10.1080/19392397.2015.1132174 file Publishers page: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1132174 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2015.1132174> Please note: Changes made as a result of publishing processes such as copy-editing, formatting and page numbers may not be reflected in this version. For the definitive version of this publication, please refer to the published source. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite this paper. This version is being made available in accordance with publisher policies. See http://orca.cf.ac.uk/policies.html for usage policies. Copyright and moral rights for publications made available in ORCA are retained by the copyright holders. “Imagining others more complexly”: Celebrity and the ideology of fame among YouTube’s ‘Nerdfighteria’ ABSTRACT: YouTube has witnessed the growth of a celebrity culture of its own. This article explores the celebritification of online video-bloggers in relation to their own discursive community. Focusing on the VlogBrothers (John and Hank Green) and their community ‘Nerdfighters’, this article demonstrates how their philosophy of “Imagining Others More Complexly” (IOMC) is used to debate ‘celebrity’ and its legitimacy. Their vision of celebrity is egalitarian and democratic, rooted in Western culture’s ‘expressive turn’ (Taylor, 1989). -

An Introduction to Virality Metrics

Association for Information Systems AIS Electronic Library (AISeL) UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2016 UK Academy for Information Systems Spring 4-12-2016 WHAT IS VIDEO VIRALITY? AN INTRODUCTION TO VIRALITY METRICS Joseph Asamoah University of Salford, [email protected] Adam Galpin University of Salford, [email protected] Aleksej Heinze University of Salford, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2016 Recommended Citation Asamoah, Joseph; Galpin, Adam; and Heinze, Aleksej, "WHAT IS VIDEO VIRALITY? AN INTRODUCTION TO VIRALITY METRICS" (2016). UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2016. 8. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2016/8 This material is brought to you by the UK Academy for Information Systems at AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). It has been accepted for inclusion in UK Academy for Information Systems Conference Proceedings 2016 by an authorized administrator of AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). For more information, please contact [email protected]. What is video virality? An introduction to virality metrics. Joseph Asamoah The University of Salford, Salford UK. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Video virality is acknowledged by many marketing professionals as an integral aspect of digital marketing. It is being mentioned a lot as a buzz word but there has not been any definitive terminology ascribed to what exactly it is. It is common to hear a phrase such as, “this video has gone viral”. However, this