Robert Louis Stevenson by GK CHESTERTON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson Adapted by Bryony Lavery

TREASURE ISLAND BY ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON ADAPTED BY BRYONY LAVERY DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. TREASURE ISLAND Copyright © 2016, Bryony Lavery All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of TREASURE ISLAND is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for TREASURE ISLAND are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London, England, W1F 0LE. -

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

A Héber És Az Árja Nyelvek Ősi Rokonságáról

A HÉBER ÉS AZ ÁRJA NYELVEK ŐSI ROKONSÁGÁRÓL ÍRTA D2 ENGELMANN GÉZA Vox diversa sonat. Populorum est vox tamen una. Martialis. BUDAPEST, 1943 A szerző fentartja jogait, a fordítás jogát is. A kiadásért felelős: Dr. Engelmann Géza. 3973. Franklin-Társulat nyomdája. — Ltvay ödön„ BREYER RUDOLF EMLÉKÉNEK Erat autem terra labii unius, et sermo- num eorumdem. Genesis XI. 1. Es gibt alté durch die historische eritik in acht und bann gethane meldungen, derén untilg- barer grund sich immer wieder luft macht, wie man sagt dasz versunkne sch&tze nach- blühen und von zeit zu zeit ina schosz der erde aufw&rts rücken, damit sie endlich noch gehoben werden. Jacób Grimm (Vorrede zur Geschichte der deutschen sprache.) I. Poéta fai, e canfcai di quel giusto flgliuol d'Anchise che venne daTroia poi che'l superbo Ili5n fa combusto. Dante, lnferno, I. 73# A szerelem könyörtelen istennője egyszer maga is szerelemre lobbant. Erről szól egy régi görög ének, a homerosi himnuszok egyike. Anohises, pásztorok királya volt az, akibe beleszeretett Aphrodité. Szégyenszemre, halandó emberbe. így akarta a kárörvendő végzet. Nem bírta az istennő sem a kínzó vágyat. Felöltözött királykisasszonynak és fölkereste Anchi- sest az Idahegyen. Éppen egyedül volt otthon. Bojtárjai a hegy oldalán legeltették nyájait. Otreus király leánya vagyok, szólt Aphrodité szendén. Hírből ismered, ugye, az édesapámat? Azért jöttem, hogy meghívjalak mihozzánk, mert Hermes isten megjósolta nekem, hogy te leszel a párom. Gyere velem édes apámhoz ós kérd meg a kezemet. Szép hozományom is van, és kelengyém királyleányhoz illő. Anchises csak nézte, nézte az égi tüneményt. Aztán férfiasan válaszolt: Nem kell ehhez édesapád. Ölelő karjába zárta. -

On the Months (De Mensibus) (Lewiston, 2013)

John Lydus On the Months (De mensibus) Translated with introduction and annotations by Mischa Hooker 2nd edition (2017) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations .......................................................................................... iv Introduction .............................................................................................. v On the Months: Book 1 ............................................................................... 1 On the Months: Book 2 ............................................................................ 17 On the Months: Book 3 ............................................................................ 33 On the Months: Book 4 January ......................................................................................... 55 February ....................................................................................... 76 March ............................................................................................. 85 April ............................................................................................ 109 May ............................................................................................. 123 June ............................................................................................ 134 July ............................................................................................. 140 August ........................................................................................ 147 September ................................................................................ -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

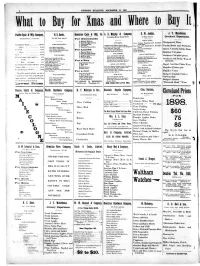

What to Buy Lor Mas and Where to My I

V f" - t ' AM&t, ' - iv' 'vTw TT' "" PVj.$ 'fiSf' rrt'fr l;"". , ;' EVENING BULLETIN, DECEMBER 18 1807. What to Buy lor Mas and Where to My I " & E. W, Jordan J. T. Waterhouse, Pacific Cycle & Mfg. Company, N. S, Sachs Hawaiian Cycle & Mfg, Co, A, E. Mnrphy Company, Arlington lllock, Hotel .Street. 10 Fort Street. Orookory Department. Km. kin Iti.iio., KoiitKt. No. 520 Fort Street. For Oentlemen KOlt A LADY: A Hawaii Wcycle "NYtiro A Search Light Lamp FOIt MKN: Kino Leather Shopping and llandkur-ehlo- f "Wedgowood llemlngtou Dlrylc SSiOO FOWOKNTLKMKN: A Punching Hag Iligs A Sweater Congress and Oxford Ijieed Shoes Kmhrohlorcd llandker- Uiists Kangaroo ltenl I.aoo and I'uriun and Statuettes " Dny's " l")00 I'lnoSllkUinbiclhs A Peerless Typewriter. In Kroneh Patont Leather and ehiefs Ilandsouio Silk Scarfs II.t f'uir milt Vnnl Calf Silk Dress and Trimmings Queen Vietoriu. Jubilee Ore-ce- nt " 75 00 ' Homcos Busts Uox of I'ino Handkerchiefs For Ladies lllaek and Colored Work liaskets Uox SlipjHirs, lllaek and Colored. SeKsors, Out-glu- ' Hoy's " 50 (X) of Silk Socks. A Hawaii IJIdyela Cases of Ruinb(w ss A Search Light Lamp FOIt LADI1: " " 4o (K) KOIl AOKNTLKMAN: aiton VOll LADIIX: A Veader Cyelometer Cut-gla- ss A Dlcyelc Hell liuii and llutton Oxfoids Ordinnry pieces .Dloyele I.aiup (extra quality)... 5 00 French Kid, Dongola Kid leather Dressing Cases Ileal IjHcu Handkerchiefs A Tennis Dacket. ' Whlto and Urown Canvas lloinstltehetl Ilandkorchlefs Crockery and China " Saddle " " ... "00 IIiukIhoiiio Ulack Idico Sc.ufs Cloth Top Smoking Cap. Ware of a. -

The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group

Maine State Library Digital Maine Academic Research and Dissertations Maine State Library Special Collections 2019 In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group Christina A. Barber IDSVA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Barber, Christina A., "In the Mouth of the Woolf: The Posthumanistic Theater of the Bloomsbury Group" (2019). Academic Research and Dissertations. 29. https://digitalmaine.com/academic/29 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine State Library Special Collections at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE MOUTH OF THE WOOLF: THE POSTHUMANISTIC THEATER OF THE BLOOMSBURY GROUP Christina Anne Barber Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy August, 2019 ii Accepted by the faculty at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Committee Chair: Simonetta Moro, PhD Director of School & Vice President for Academic Affairs Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: George Smith, PhD Founder & President Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts Committee Member: Conny Bogaard, PhD Executive Director Western Kansas Community Foundation iii © 2019 Christina Anne Barber ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iv Mother of Romans, joy of gods and men, Venus, life-giver, who under planet and star visits the ship-clad sea, the grain-clothed land always, for through you all that’s born and breathes is gotten, created, brought forth to see the sun, Lady, the storms and clouds of heaven shun you, You and your advent; Earth, sweet magic-maker, sends up her flowers for you, broad Ocean smiles, and peace glows in the light that fills the sky. -

The Literary Development of Robert Louis Stevenson a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Science, Literature and A

The Literary Development of Robert Louis Stevenson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Science, Literature and Arts of the University of innesota, in partial f'Ulfillment of the requirements ror the Degree of Master of Arts By Ethel N. McCauley 1911 6 0 Bibliography A. For criticism on Stevenson as an author and a stylist the following are important: R. Burton, Literary Likings H. B. Baldwin, Life study in Criticism J . Chapman, Emerson and Other Essays G. K. Chesterton, Varied Types J. Guiller couch, Adventures in Criticism J. J . Dawson, Characteristics of Fiction E. Gosse, Critical Kit Kats H . James, Partial Portraits A. Lang, Essays in Little B. Mathews, Aspects of Fiction • L. Phelps, Essays on Modern Novelists B. Torrey, Friends on the Shelf N. Raleigh, Robert Louis Stevenson L. Stephen, Studies Of a Biographer A. H. Japp, Robert Louis Stevenson I must acknowledge indebtedness to these able dissertations. B. For fU.rther criticism on Stevenson's literary development, see, especially: No. Am. 171, The Art of Stevenson Cent. ?.9, Stevenson and his Writing Sat R. 81, Catriona Fortn. 62, Critical study of Stevenson West. 139, some Aspects of the ork by Stevenson Sat. R. 81, Weir of Hermiston Liv. Age ?.21, Essayist, Novelist and Poet Acad. 58, His rank as a Writer Critic a, His Style and his Thot Nat . 14, Methods of Stevenson , - c. The following works of Robert Louis Stevenson were used for a study of his style: Weir of Hermiston, Edited c.scribner & Sons 1905 II II Treasure Island, 11 II II Travels with a Donkey, 11 II Prince Otto, » II II II New Arabian Nights, 11 II II Merry Men, 11 Memories and Portraits, 11 II II Memoir of Fleening Jenkin, 11 II 189-> The Master of Ballantrae, 11 II 1905 Letters, It II 1901 Kidnapped, II II 1905 II Island Nights Entertainments, 11 11 II An Inland Voyage, 11 11 II Familiar studies of Men and Books, 11 Tables, Edited 11 1906 Ebb Tide, 11 11 1905 David Balfour, II II II Silverado Squatters, II II II Across the Plains, II II II j D. -

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON HEROES of ALL TIME FIRST VOLUMES Mohammed

OBER1 .GUIS university of Connecticut a> i libraries :v CV» COSt*W PR 5L93 C7 3 1153 0nt4S37 l£>tf& 3**-- ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON HEROES OF ALL TIME FIRST VOLUMES Mohammed. By Edith Holland. Alexander the Great. By Ada Russell, M.A (Vict.) Augustus. By Rene Francis, B.A. Alfred the Great. By A. E. McKilliam, M.A. Thomas Becket. By Susan Cunnington. Jeanne d'Arc. By E. M. Wilmot-Buxton, F.R.Hist.S. Sir Walter Raleigh. By Beatrice Marshall. William the Silent. By A. M. Miall. Marie Antoinette. By Alice Birkhead, B.A. Boys who Became Famous. By F. J. Snell. Oliver Cromwell. By Estelle Ross. Peter the Great. By Alice Birkhead, B.A. The Girlhood of Famous Women. By F. J. Snell. Garibaldi and his Red-Shirts. By F. J. Snell. Robert Louis Stevenson. By Amy Cruse. Queen Victoria. By E. Gordon Browne, M.A. Anselm. By E. M. Wilmot-Buxton, F.R.Hist.S. Sir Walter Scott. By Amy Cruse. William the Conqueror. By Rene Francis, B.A. Julius Caesar. By Ada Russell, M.A. Buddha. By Edith Holland. William Caxton. By Susan Cunnington. Chaucer. By Amy Cruse. Charles XII. By Alice Birkhead, B.A. Queen Elizabeth. By Beatrice Marshall. Warwick the King-maker. By Rene Francis, B.A. Many other volumes in active preparation Fr, R. L, S. in the South Seas From a photograph toy John Patrick ROBERT LOUIS r STEVENSON AMY CRUSE AUTHOR OF ' ' ENGLISH LITERATURE THROUGH THE AGES 1 ' SIR WALTER SCOTT ' ' CHARLOTTE BRONTE 1 ELIZABETHAN LYRISTS ' ETC. WITH TEN ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON GEORGE G. -

Ward, Christopher J. (2010) It's Hard to Be a Saint in the City: Notions of City in the Rebus Novels of Ian Rankin. Mphil(R) Thesis

Ward, Christopher J. (2010) It's hard to be a saint in the city: notions of city in the Rebus novels of Ian Rankin. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1865/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City: Notions of City in the Rebus Novels of Ian Rankin Christopher J Ward Submitted for the degree of M.Phil (R) in January 2010, based upon research conducted in the department of Scottish Literature and Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow © Christopher J Ward, 2010 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction: The Crime, The Place 4 The juncture of two traditions 5 Influence and intent: the origins of Rebus 9 Combining traditions: Rebus comes of age 11 Noir; Tartan; Tartan Noir 13 Chapter One: Noir - The City in Hard-Boiled Fiction 19 Setting as mode: urban versus rural 20 Re-writing the Western: the emergence of hard-boiled fiction 23 The hard-boiled city as existential wasteland 27 ‘Down these mean streets a man must -

Fashion Through the Ages

Fashion Through The Ages • In the Victorian era, both boys and girls wore dressed until the age of around 5 years old. • High-heeled shoes were worn from the 17th century, and were initially designed for men. • Women often wore platform shoes in the 15th to 17th centuries, which kept their skirts up above the muddy streets. • Wearing purple clothes has been associated with royalty since the Roman era. The dye to make clothes purple, made from snail shells, was very expensive. • Napoleon was said to have had buttons sewn onto the sleeves of military jackets. He hoped that they would stop soldiers wiping their noses on their sleeves! • Vikings wore tunics and caps, but they never wore helmets with horns. • See the objects in the Museum collections all about looking good: http:// heritage.warwickshire.gov.uk/museum-service/collections/looking-good/ • View the history of fashion from key items in the collection at Bath’s Fashion Museum: https://www.fashionmuseum.co.uk/galleries/history- fashion-100-objects-gallery • Google’s ‘We Wear Culture’ project includes videos on the stories behind clothes: https://artsandculture.google.com/project/fashion • Jewellery has been key to fashion for thousands of years. See some collection highlights at the V&A website: https://www.vam.ac.uk/ collections/jewellery#objects A Candy Stripe Friendship Bracelet Before you begin you need to pick 4 – 6 colours of thread (or wool) and cut lengths of each at least as long as your forearm. The more pieces of thread you use, the wider the bracelet will be, but the longer it will take. -

Notices of Fungi in Greek and Latin Authors Rev

This article was downloaded by: [McGill University Library] On: 12 February 2015, At: 11:10 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Series 5 Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah11 V.—Notices of fungi in Greek and Latin authors Rev. William Houghton M.A. F.L.S. Published online: 07 Oct 2009. To cite this article: Rev. William Houghton M.A. F.L.S. (1885) V.—Notices of fungi in Greek and Latin authors , Annals and Magazine of Natural History: Series 5, 15:85, 22-49, DOI: 10.1080/00222938509459293 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222938509459293 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.