Scottish Bathing Waters Report 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frommer's Scotland 8Th Edition

Scotland 8th Edition by Darwin Porter & Danforth Prince Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers About the Authors Darwin Porter has covered Scotland since the beginning of his travel-writing career as author of Frommer’s England & Scotland. Since 1982, he has been joined in his efforts by Danforth Prince, formerly of the Paris Bureau of the New York Times. Together, they’ve written numerous best-selling Frommer’s guides—notably to England, France, and Italy. Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5744 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per- mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572-4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

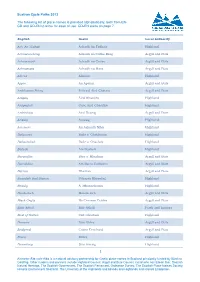

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

MSBO Report 2016

Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory 2016 Report 1 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory (MSBO) SW Kintyre – Argyll PA28 6PZ Established September 1993 2016 Report Compiled by Eddie Maguire Unless stated photographs in this report are by the warden Cover photos – Dunlins / MSBO and a juvenile Northern Gannet The beautiful village of Machrihanish / Photo – Stuart Andrew Contents... Introduction and Highlights 2016... 4 Overland passage of Northern Gannets in south Argyll... 4 Unprecedented autumn passage of Curlew Sandpipers at Machrihanish... 5 North American duck off MSBO... 6 Monthly Reports... 6 Acknowledgements... 53 Movements of Goldfinch in Argyll 2009 – 2016... 54 2 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Sub-adult Pomarine Skua 4th May First-winter Iceland Gull 24th March 3 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Introduction to 2016 Report... The MSBO was manned daily 1st March – 31 October with casual observations later. The 2016 Report portrays the year with a monthly summary of the main ornithological events accompanied by a selection of 83 photographs. Visit www.machrihanishbirdobservatory.org.uk Highlights of the year... Resolute daily observations ultimately produced records of scarce/unusual species and excellent totals of many regular passage visitors. Without doubt, the most extraordinary events of the year involved an 8km overland passage by almost three hundred adult Northern Gannets and an unprecedented passage of Curlew Sandpipers. Summary of overland passage by Northern Gannets in south Argyll... During August-October 2016, the MSBO warden arranged regular surveillance at Campbeltown harbour, S Kintyre, Argyll to determine the scale of overland passage by Northern Gannets Morus bassanus. -

Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications 12Th July 2019.Pdf

Weekly Planning list for 12 July 2019 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 12 July 2019 12/7/2019 9:14 Weekly Planning list for 12 July 2019 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 19/00955/PP Officer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Installation of replacement windows Location: 3Wellpar k Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute, PA20 9JY Applicant: Miss J McCusker 3Wellpar k Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute , PA20 9JY Ag ent: Kenneth Wotherspoon 1Holm Street, Crossford, Carluke, ML8 5GR Development Type: N01 - Householder developments Grid Ref: 210598 - 665259 Reference: 19/01273/PP Officer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 08 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Erection of timber outdoor classroom Location: Apple Tree Nursery, 10MackinlayStreet, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute,PA20 0AY Applicant: Apple Tree NurseryLimited Apple Tree Nursery, 10MackinleyStreet, Rothesay, Scotland, PA20 0AY Ag ent: James Wilson Spr ingbank, 7Chapelhill Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,PA20 0BJ Development Type: N10B - Other developments - Local Grid Ref: 208309 - 665074 Reference: 19/01292/PP Officer: Allocated ToArea Office Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 07 - Dunoon Community Council: Dunoon Community Council Proposal: Installation of 1 x 7kW dual outlet vehicle charging unit, erec- tion of protection barriers and for mation of 2 appropriately signed bays within -

THE PLACE-NAMES of ARGYLL Other Works by H

/ THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE PLACE-NAMES OF ARGYLL Other Works by H. Cameron Gillies^ M.D. Published by David Nutt, 57-59 Long Acre, London The Elements of Gaelic Grammar Second Edition considerably Enlarged Cloth, 3s. 6d. SOME PRESS NOTICES " We heartily commend this book."—Glasgow Herald. " Far and the best Gaelic Grammar."— News. " away Highland Of far more value than its price."—Oban Times. "Well hased in a study of the historical development of the language."—Scotsman. "Dr. Gillies' work is e.\cellent." — Frce»ia7is " Joiifnal. A work of outstanding value." — Highland Times. " Cannot fail to be of great utility." —Northern Chronicle. "Tha an Dotair coir air cur nan Gaidheal fo chomain nihoir."—Mactalla, Cape Breton. The Interpretation of Disease Part L The Meaning of Pain. Price is. nett. „ IL The Lessons of Acute Disease. Price is. neU. „ IIL Rest. Price is. nef/. " His treatise abounds in common sense."—British Medical Journal. "There is evidence that the author is a man who has not only read good books but has the power of thinking for himself, and of expressing the result of thought and reading in clear, strong prose. His subject is an interesting one, and full of difficulties both to the man of science and the moralist."—National Observer. "The busy practitioner will find a good deal of thought for his quiet moments in this work."— y^e Hospital Gazette. "Treated in an extremely able manner."-— The Bookman. "The attempt of a clear and original mind to explain and profit by the lessons of disease."— The Hospital. -

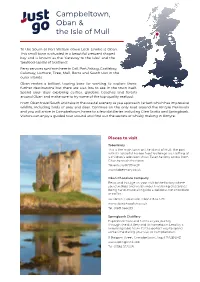

Campbeltown, Oban & the Isle of Mull

Campbeltown, Oban & the Isle of Mull To the South of Fort William down Loch Linnhe is Oban. This small town is situated in a beautiful crescent shaped bay and is known as the ‘Gateway to the Isles’ and the ‘Seafood capital of Scotland’. Ferry services run from here to Coll, Port Askaig, Castlebay, Colonsay, Lismore, Tiree, Mull, Barra and South Uist in the outer islands. Oban makes a brilliant touring base for wanting to explore these further destinations but there are also lots to see in the town itself. Spend your days exploring castles, gardens, beaches and forests around Oban and make sure to try some of the top-quality seafood. From Oban travel South and take in the coastal scenery as you approach Tarbert which has impressive wildlife, including birds of prey and deer. Continue on the only road around the Kintyre Peninsula and you will arrive in Campbeltown, home to a few distilleries including Glen Scotia and Springbank. Visitors can enjoy a guided tour around and find out the secrets of whisky making in Kintyre. Places to visit Tobermory This is the main town on the island of Mull. The port with its colourful harbor-front buildings was setting of a children’s television show. Take the ferry across from Oban to reach this town. New Picture Tobermory PA75 6QF www.tobermory.co.uk Oban Chocolate Company Relax and indulge on your visit to the factory where you can shop and watch mouth watering chocolates being hand-made alongside a delicious hot chocolate or coffee. 34 Corran, Esplanade, Oban PA34 5PS www.obanchocolate.co.uk Tel: 01631 566099 Springbank Distillery Experience tales and tastes as you journey through the distillery and its hometown. -

Bleachfield Farm by Campbeltown, Argyll & Bute

BLEACHFIELD FARM BY CAMPBELTOWN, ARGYLL & BUTE BLEACHFIELD FARM BY CAMPBELTOWN ARGYLL & BUTE A compact livestock farm set in some of the finest ground found on the Kintyre Peninsula Campbeltown 2 miles Lochgilphead 54 miles Glasgow 142 miles • Traditional 5-bedroom farmhouse • Traditional courtyard • Range of modern and traditional outbuildings • 156.6 acres of productive grazing and silage ground For Sale as a Whole About 63.3 Ha (156.6 Acres) in all Suite C Stirling Agricultural Centre Stirling FK9 4RN 01786 434600 [email protected] GENERAL Modern Sheds Bleachfield Farm is an extensive stock rearing farm situated in some of the best agricultural land found on To the west side of the steading is an extensive range of modern farm buildings, ideal for handling cattle, the Kintyre Peninsula on the west coast of Scotland. Machrihanish Bay and the Atlantic Coast lie only a which benefit from electric power and light, water troughs and concrete or stone flooring. The sheds also short distance to the north. The small settlement of Drumlemble lies a short distance away from the farm, benefit from a system of gated cattle handling facilities. on the B842 and it has a primary school. Campbeltown lies 2 miles to the east, where a large range of shops, schools and professional services can be found. Campbeltown Airport is also nearby and offers Large span cattle shed : 47.0 m x 23.0 m (approx.) Concrete portal frame with timber built lean-to regular flights to Glasgow. Glasgow is accessible via the A83 from Campbeltown and is 142 miles distant, sections. -

Flotsam and Jetsam June 2019 Welcome to the Argyll and Bute Beach Forum Quarterly E-Bulletin

Flotsam and Jetsam June 2019 Welcome to the Argyll and Bute Beach Forum quarterly e-bulletin. The Argyll and Bute Beach Forum is a project run by The GRAB Trust (as part of our Beaches and Marine Litter Project). Our main aim is to raise awareness of the impacts of and reduce beach and marine litter and to support communities to take action by cleaning beaches. We hope you will find our e-bulletin interesting. The bulletin is also available by post and on our website. Thank you to all of our wonderful volunteers who have worked hard again this year to make our beaches beautiful. Mid-Argyll & Kintyre Gigha & Drumlemble Schools have been working hard completing their MCS Surveys. Gigha Primary School undertook their 4th MCS Survey of Minister’s Beach. We noticed that this survey showed less public litter such as sweet wrappers and cigarettes. This may be because it was slightly earlier in the year so, apart from Easter, the tourist season had not fully begun. We did, however, see a larger proportion of fishing litter alt- hough in general substantially less litter was collected than in previous surveys. The P6 & 7’s also took part in ‘A Plastic World’ workshop and designed some fantastic litter collecting devices to be installed in oceans to collect existing litter. The work with The GRAB Trust is part of the schools wider sustainability and enterprise project supported by Fyne Homes Climate Challenge Fund Project. The Beaches & Marine Litter Project hopes to assist with family workshops run by the school in order to begin a community enterprise using their new 3D printer. -

Argyll Bird Report 25 2013

The Twenty Fifth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT With Systematic List for the year 2013 Edited by Jim Dickson Assisted by Robin Harvey and David Jardine Systematic List by John Bowler, Neil Brown, Malcolm Chattwood, Paul Daw, Jim Dickson, Bob Furness, Mike Harrison, David Jardine, Andy Robinson and Nigel Scriven ISSN 1363-4386 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Feb. 2015 Argyll Bird Club Scottish Charity Number SC008782 Founded in 1985, the Argyll Bird Club aims to promote interest in and conservation of Argyll’s wild birds and their natural environment. The rich diversity of habitats in the county supports an exceptional variety of bird life. Many sites in Argyll are of international importance. The Club brings together people with varied experience, from complete beginners to experts, and from all walks of life. New members are particularly welcome. Activities Every spring and autumn there is a one-day meeting with illustrated talks and other activities. These meetings are held in conveniently central locations. Throughout the year there are field trips to local and more distant sites of interest. Publications The annual journal of the Club is the Argyll Bird Report, containing the Systematic List of all species recorded in the county during the year, together with reports and articles. The less formal quarterly newsletter, The Eider, gives details of forthcoming events and activities, reports of recent meetings, bird sightings, field trips, articles, and shorter items by members and others. Website www.argyllbirdclub.org To apply for membership, please (photocopy and) complete the form below and send to our Membership Secretary: Sue Furness, The Cnoc, Tarbet, G83 7DG. -

Musical Resonances Between Argyll and Antrim Stuart Eydmann

Antrim and Argyll 11/6/18 22:13 Page 97 4 Sounds Across the Moyle: Musical Resonances Between Argyll and Antrim Stuart Eydmann Introduction It is important to remember that the traffic has always been in both directions; if the most important single event in early Scottish history can be said to have been the foundation of the kingdom of Dalriada by Scoti (Irish Gaels) who had crossed that same strip of water, it is also true that Ulster history has often been influenced by visitors from across the Moyle. It was not for mere literary effect that Camden (in his Britannia ) described the peninsula of Kintyre as thrusting itself ‘greedily towards Ireland’. Another historical fact which has to be borne in mind, when one scrutinises the cultural mix, is that both Ulster and Kintyre were successfully colonised, in the seventeenth century, by Lowlanders from Renfrewshire and Ayrshire, and that in both areas the Gaelic language has co-existed with Lowland Scots right up to the present century.1 With Antrim and Argyll closely separated, or rather joined, by the Straits of Moyle or North Channel, logic would suggest that there must have been, and might still be, musics that resonate across those waters. Indeed, it is generally accepted that music and song has been carried and passed between Scotland and Ireland for centuries and traditional musicians know that even the gentlest of scraping beneath the surface of many songs or tunes will reveal or suggest equivalents in each country. It is possible, therefore, to find material heard in Antrim that can be traced back to or from, or shared with Scotland, or music in Argyll that links to greater Ireland. -

Kintyre Ryburns

Kintyre Ryburns By Roderick James Ryburn, Canberra, ACT, Australia On a beautiful sunny day in September, 2007, my wife Christine, daughter Jessica and I drove the very scenic journey from Glasgow to Campbeltown, near the knob (the ‘Mull’) on the end of the long Kintyre Peninsula, on the west coast of Scotland. My main purpose was to learn something about the lives of the ancestors of all New Zealand Ryburns, including me. That afternoon, in the Old Kilkerran Graveyard in Campbeltown, Jessica found the ivy-fringed gravestone of James Ryburn, baker and farmer, who died at age 66 in 1857. He was my great, great grandfather, and I call him “James the Baker”. That evening we stayed in bed-and-breakfast accommo- dation at ‘East Drumlemble’ farmhouse (Fig. 11), about 6 km west of Campbeltown, on the road to Machrihanish (Fig. 4). This is a dairy farm now run by the Ralstons, a well- known Kintyre name, that along with Ryburn, Armour and many other names, ultim- ately came from Ayrshire in the 1600’s. I already knew that James the Baker was born near Drumlemble Village, but it was only some months later I discovered that this partic- ular farmhouse was built in 1800 by his uncle, “James the Farmer”. However, all good things come to an end, and, as I learned later, the Ryburns were booted out of several farms by their landlord, that powerful Scottish lord the Duke of Argyll. You could say they were late victims of the Highlands clearances. Fig. 1. ‘James the Baker’s’ Gravestone in Kilkerran Graveyard This trip kindled my interest in conducting further research into the Kintyre Ryburns, their lives and times.