Background Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Priory Hospital Altrincham Newapproachcomprehensive Report

The Priory Hospital Altrincham Quality Report Rappax Road, Hale, Altrincham, Cheshire, WA15 0NX Tel: 0161 904 0050 Date of inspection visit: 11 and 12 January 2016 Website: www.priorygroup.com Date of publication: 19/05/2016 This report describes our judgement of the quality of care at this location. It is based on a combination of what we found when we inspected and a review of all information available to CQC including information given to us from patients, the public and other organisations Ratings Overall rating for this location Good ––– Are services safe? Good ––– Are services effective? Good ––– Are services caring? Good ––– Are services responsive? Good ––– Are services well-led? Good ––– Mental Health Act responsibilities and Mental Capacity Act and Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards We include our assessment of the provider’s compliance with the Mental Capacity Act and, where relevant, Mental Health Act in our overall inspection of the service. We do not give a rating for Mental Capacity Act or Mental Health Act, however we do use our findings to determine the overall rating for the service. Further information about findings in relation to the Mental Capacity Act and Mental Health Act can be found later in this report. 1 The Priory Hospital Altrincham Quality Report 19/05/2016 Summary of findings Overall summary We rated The Priory Hospital Altrincham as good • staff were polite, friendly, caring and respectful. because: Patients told us staff had a lot of time for them. Staff had a good understanding of patients’ needs and • wards were safe for patients and staff did risk involved relatives in patients’ care. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Manchester M2 6AN Boyle 7 C Brook Emetery Track Telephone 0161 836 6910 - Facsimile 0161 836 6911

Port Salford Project Building Demolitions and Tree Removal Plan Peel Investments (North) Ltd Client Salford CC LPA Date: 28.04.04 Drawing No.: 010022/SLP2 Rev C Scale: 1:10 000 @Application A3 Site Boundary KEY Trees in these areas to be retained. Scattered or occasional trees within these areas to be removed SB 32 Bdy t & Ward Co Cons SL 42 Const Bdy Boro Chat Moss CR 52 Buildings to be Demolished MP 25.25 OAD B 62 ODDINGTON ROA STANNARD R Drain 9 8 72 D 83 43 5 6 GMA PLANNING M 62 36 35 SP 28 35 27 48 3 7 2 0 19 4 0 Drain C HA Drain TLEY ROAD 3 MP 25.25 6 23 King Street, Manchester M2 6AN 12 Planning and Development Consultants Chat Moss 11 CR 32 rd Bdy Wa nst & Co Co Bdy Const e-mail [email protected] o Bor 2 53 8 1 Telephone 0161 836 6910 - Facsimile 0161 836 6911 22 Barton Moss 10 16 ROAD F ETON OXHIL BRER 9 rain 43 D L ROAD 23 Drain 2 0 St Gilbert's 33 Catholic Church MP 25 Presbytery 10 3 2 2 4 Drain Barton Moss 2 Drain Drain CR Drain 1 13 15 Co Const Bdy 6 Track Barton Moss 16 Dra Boro Const and Ward Bdy in MP 24.75 27 Eccles C of E High S Drain FLEET ROAD 6 3 ORTH 26 N SL chool D rain 0 3 Drain 39 Drai n 36 Drain BUC KT HORN D E L OA R Drain AN E D ra ILEY in H M 62 53 44 51 55 Dra 5 9 0 5 in M 62 Drain Brookhouse k Sports Centre Barton Moss Primary School rac T 0 6 63 H ILEY ROA D 6 N 5 O BU RTH D 78 rai 2 CK FLEE n T 67 4 35 H O 3 3 54 RN LA 6 T Pavilion 3 ROAD 75 N 74 E 34 27 25 18 78 6 20 7 80 88 Drain 1 1 TRIPPIER ROAD 6 56 23 58 0 30 6 3 1 n 32 55 89 9 2 7 Drai 6 1 9 6 93 64 3 2 15 95 59 ROCHFORD R 59 2 9 15 66 -

Alphabetical Directory. Had-Hal 639

DIRECTORY.] ALPHABETICAL DIRECTORY. HAD-HAL 639 Hadfield Robert, clerk, 75 IIerbert street, B Ilaigh S. Emily (Miss), school, 21 Derby road, W Hadfield Robt. househldr.21 Stockport rd.Cheadle Heath Hmgh Sanurel, gardener, 'l'n.11Iord rd. Alderley Edge Hadfield Samuel, housekeeper, 362 Market street, D Haigh Thomas, foreman, 106 Heddish rd. South Reddish Hadfield Sidney, salBS'Illan, 94 Rocky lane, Monton Haigh Thorne, master mariner, 2 Milton st. Stretford Hadfield Squire, bricklayer, 77 Ashton New road, D Haigh William, dyer, 74 Frederick street, Deuton Hadfield Thomas, clerk, 64 De.an street, l''ailsworth Haigh William, fitter, 9 Hilda street, M Hadfield Thomas, foreman, 42 Pitt st·root, H H Haigh William, gardener, g Watson street, H Hadfie-ld Thomas, traveller, 553 Manchester rd. Denton Haigh 1Villiam, labourer, 4 Union street, S Hadfield Thos. A. househDlder, 13 Swayfield av.C cum H Haight Frederick, traveller, 7 Langdale avenue, L Hadfield William, householder, 30 Chapel st. Didsbury Haighton Bertha (Mrs.), householder, 23 Ed '1\ ard road, Hadfield William, overlooker, 3 ra, High street, D Hiaher,., B Hadfield \Villiam, weaver, 19 Droylsden road, D Hailstone "\'Valt. Jn. grocer, Apsley ter.Flixton rd. Flixtn Hadley Edward & Sons, builders & contractors, IS Shavr Hailwood A. dairyman, Grange Farm dairy, 13 Gilda. ro3d; ·workshop, 4 Moorfield grove, Heaton Moor Brook road, E Hadley Edward, builder & contractor (Edward Iladley & Haimes J osepb, painter, Moss rose, Alderley Edge Sons) ; 8 Laurel road, Hea ton .Moor Ilaines J ames, mechanic, 3 8 !'ark street, 8 Hadley Edward, jun. builder (Edward Hadley & Sons), Haines Thomas, householder, 147 Station rd. Pendlebury Shawfold, Shaw road, Heaton Moor Haines ·waiter S. -

Pharmacy Name

Pharmacy Name Address Postcode Signed up ASDA PHARMACY Traders Avenue, Barton Dock Road, Urmston, Manchester M41 7ZA Trafford Yes BLADON B (HALE) LTD 219 Ashley Road, Hale, Altrincham , Cheshire WA15 9SZ Trafford Yes BOOTS PHARMACY 179 Canterbury Road, Davyhulme, Urmston, Manchester M41 0SE Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED 2 The Mall, Sale M33 7XZ Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED Trafford Retail Park, Urmston , Manchester M41 7FN Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED Unit 14, Golden Way, Manchester, Lancashire M41 0NA Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED 10 Peel Avenue, The Trafford Centre , Manchester M17 8BD Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED George Street, MSU 1 Stamford Quarter, George Street, Altrincham WA14 1RJ Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED Unit 8b George Richards Way, Altrincham Retail Park , Altrincham WA14 5GR Trafford Yes BOOTS UK LIMITED 69-72 Stretford Mall, Chester Road, Manchester, Greater Manchester M32 9BD Trafford Yes BOWDON PHARMACY Vicarage Lane, Bowden , Cheshire WA14 3BD Trafford Yes BROADHEATH PHARMACY 70 Manchester Road, Broadheath , Altrincham, Cheshire WA14 4PJ Trafford Yes BROOKS BAR PHARMACY 162-164 Chorlton Road, Old Trafford, Manchester M16 7WW Trafford Yes BROOMWOOD PHARMACY LTD 63 Briarfield Road, Timperley, Altrincham , Cheshire WA15 7DD Trafford Yes C & T PHARMACY 77 Great Stone Road, Stretford , Manchester M32 8GR Trafford Yes COHENS CHEMIST 177 Ashley Road, Hale, Altrincham, Cheshire WA15 9SD Trafford Yes COHENS CHEMIST Firsway Health Centre, 121 Firsway, Sale , Manchester M33 4BR Trafford Yes CONRAN LATE NIGHT PHARMACY 175 Moorside -

NOTICE of ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION Trafford Council Election of District Councillors for the Wards listed below Number of Number of District District Wards Wards Councillors to Councillors to be elected be elected Altrincham One Hale Barns One Ashton Upon Mersey One Hale Central One Bowdon Two Longford Two Broadheath One Priory Two Brooklands One Sale Moor One Bucklow-St Martins One St Mary's One Clifford One Stretford One Davyhulme East One Timperley One Davyhulme West One Urmston One Flixton Two Village One Gorse Hill One 1. Nomination papers for this election can be downloaded from the Electoral Commission website or may be obtained from the Returning Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Completed nomination papers must be delivered by hand to the Returning Officer, Committee Room 1 Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH, on any weekday (Monday to Friday inclusive (excluding bank and public holidays)) after the date of this notice on between 10am and 4pm but no later than 4pm on Thursday 8 April 2021. 3. If any election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday 6 May 2021. 4. Applications to register to vote at this election must reach the Electoral Registration Officer by 12 midnight on Monday 19 April 2021.Applications may be made online: www.gov.uk/register to vote or sent directly to the Electoral Registration Officer at Room SF.241, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford, M32 0TH. -

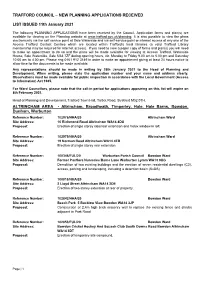

Trafford Council – New Planning Applications Received

TRAFFORD COUNCIL – NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 11th January 2021 The following PLANNING APPLICATIONS have been received by the Council. Application forms and plan(s) are available for viewing on the Planning website at www.trafford.gov.uk/planning. It is also possible to view the plans electronically via the self service point at Sale Waterside and via self-service point or internet access at any one of the Access Trafford Contact Centres which are located within Trafford’s local libraries (a valid Trafford Library membership may be required for internet access). If you need to view a paper copy of forms and plan(s) you will need to make an appointment to do so and the plans will be made available for viewing at Access Trafford, Waterside House, Sale Waterside, Sale M33 7ZF during opening hours, viz. Monday to Friday 9.00 am to 5.00 pm and Saturday 10.00 am to 4.00 pm. Please ring 0161 912 3149 in order to make an appointment giving at least 24 hours notice to allow time for the documents to be made available. Any representations should be made in writing by 28th January 2021 to the Head of Planning and Development. When writing, please state the application number and your name and address clearly. Observations must be made available for public inspection in accordance with the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. For Ward Councillors, please note that the call-in period for applications appearing on this list will expire on 8th February 2021. Head of Planning and Development, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford M32 0TH. -

Apartment 27, St. Andrews Court Queens Road, Hale Cheshire, Wa15 9Jf

APARTMENT 27, ST. ANDREWS COURT QUEENS ROAD, HALE CHESHIRE, WA15 9JF FLOOR PLANS Not to Scale. For Illustration purposes only. 162/164 Ashley Road, Hale, Cheshire WA15 9SF Tel: 0161 929 6363 Fax: 0161 929 6333 NOTICE: John N Hilditch & Co. for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose agents they are give notice that: (i) the particulars are set out as a general outline only for the guidance of intending purchasers or lessees, and do not constitute, nor constitute part of, an offer or contract; (ii) all descriptions, dimensions, references to condition and necessary permissions for use and occupation, and other details are given in good faith and are believed to be correct but any intending purchasers or tenants should not rely on them as statements or representations of fact but must satisfy themselves by inspection or otherwise as to the correctness of each of them; (iii) no person in the employment of John N Hilditch & Co. has any authority to make or give any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. APT 27, ST. ANDREWS COURT, QUEENS ROAD HALE Offered for sale in need of complete FIRST FLOOR & LANDING cosmetic modernisation, this first floor retirement flat forms part of a highly L SHAPED ENTRANCE HALLWAY popular development sitting within easy LIVING ROOM 13’5” x 9’6” (4.1 x 2.9) KITCHEN 7’7” x 6’11” (2.3 x 2.1) striking distance of both Hale and BEDROOM 10’6” x 9’10” (3.2 x 3) Altrincham. SHOWER ROOM The accommodation comprises a communal entrance with communal lounge and facilities with a lift and staircase to the first floor and a generous landing. -

New Planning Applications Received List

TRAFFORD COUNCIL – NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 3rd August 2020 The following PLANNING APPLICATIONS have been received by the Council. Application forms and plan(s) are available for viewing on the Planning website at www.trafford.gov.uk/planning. It is also possible to view the plans electronically via the self service point at Sale Waterside and via self-service point or internet access at any one of the Access Trafford Contact Centres which are located within Trafford’s local libraries (a valid Trafford Library membership may be required for internet access). If you need to view a paper copy of forms and plan(s) you will need to make an appointment to do so and the plans will be made available for viewing at Access Trafford, Waterside House, Sale Waterside, Sale M33 7ZF during opening hours, viz. Monday to Friday 9.00 am to 5.00 pm and Saturday 10.00 am to 4.00 pm. Please ring 0161 912 3149 in order to make an appointment giving at least 24 hours notice to allow time for the documents to be made available. Any representations should be made in writing by 20th August 2020 to the Head of Planning and Development. When writing, please state the application number and your name and address clearly. Observations must be made available for public inspection in accordance with the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. For Ward Councillors, please note that the call-in period for applications appearing on this list will expire on 31st August 2020. Head of Planning and Development, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford M32 0TH. -

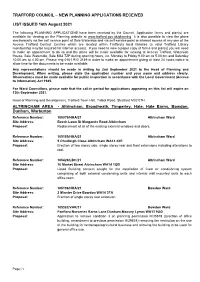

NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 16Th August 2021 ALTRINCHAM AREA

TRAFFORD COUNCIL – NEW PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED LIST ISSUED 16th August 2021 The following PLANNING APPLICATIONS have been received by the Council. Application forms and plan(s) are available for viewing on the Planning website at www.trafford.gov.uk/planning. It is also possible to view the plans electronically via the self service point at Sale Waterside and via self-service point or internet access at any one of the Access Trafford Contact Centres which are located within Trafford’s local libraries (a valid Trafford Library membership may be required for internet access). If you need to view a paper copy of forms and plan(s) you will need to make an appointment to do so and the plans will be made available for viewing at Access Trafford, Waterside House, Sale Waterside, Sale M33 7ZF during opening hours, viz. Monday to Friday 9.00 am to 5.00 pm and Saturday 10.00 am to 4.00 pm. Please ring 0161 912 3149 in order to make an appointment giving at least 24 hours notice to allow time for the documents to be made available. Any representations should be made in writing by 2nd September 2021 to the Head of Planning and Development. When writing, please state the application number and your name and address clearly. Observations must be made available for public inspection in accordance with the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985. For Ward Councillors, please note that the call-in period for applications appearing on this list will expire on 13th September 2021. Head of Planning and Development, Trafford Town Hall, Talbot Road, Stretford M32 0TH. -

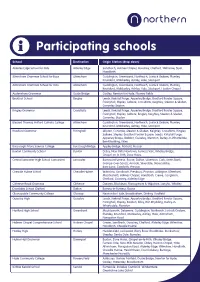

Participating Schools

Participating schools School Destination Origin Station (drop down) Alderley Edge School for Girls Alderley Edge Sandbach, Holmes Chapel, Goostrey, Chelford, Wilmslow, Styal, Handforth Altrincham Grammar School for Boys Altrincham Cuddington, Greenbank, Northwich, Lostock Gralam, Plumley, Knutsford, Mobberley, Ashley, Hale, Stockport Altrincham Grammar School for Girls Altrincham Cuddington, Greenbank, Northwich, Lostock Gralam, Plumley, Knutsford, Mobberley, Ashley, Hale, Stockport, Heaton Chapel Audenshaw Grammar Guide Bridge Godley, Newton for Hyde, Flowery Fields Beckfoot School Bingley Leeds, Kirkstall Forge, Apperley Bridge, Bradford Forster Square, Frizinghall, Shipley, Saltaire, Crossflatts, Keighley, Steeton & Silsden, Cononley Skipton Bingley Grammar Crossflatts Leeds, Kirkstall Forge, Apperley Bridge, Bradford Forster Square, Frizinghall, Shipley, Saltaire, Bingley, Keighley, Steeton & Silsden, Cononley, Skipton Blessed Thomas Holford Catholic College Altrincham Cuddington, Greenbank, Northwich, Lostock Gralam, Plumley, Knutsford, Mobberley, Ashley, Hale, Stockport Bradford Grammar Frizinghall Skipton, Cononley, Steeton & Silsden, Keighley, Crossflatts, Bingley, Saltaire, Shipley, Bradford Forster Square, Leeds, Kirkstall Forge, Apperley Bridge, Baildon, Guiseley, Menston, Burley-in-Wharfedale, Ben Rhydding, Ilkley Burscough Priory Science College Burscough Bridge Appley Bridge, Parbold, Hoscar Buxton Community School Buxton Disley, New Mills Newtown, Furness Vale, Whaley Bridge, Chapel-en-le-Frith, Dove Holes Central Lancaster -

Hale Village Place Plan Final September 2020

Hale Village Place Plan Final September 2020 Contents Content 1. Introduction 6 2. Hale Village 10 3. Community Activity 16 4. Baseline Analysis 24 5. The Vision and Objectives 38 6. Development Strategy 44 7. Movement Strategy 60 8. Shopfront Strategy 66 9. Action Plan 74 Introduction 01 1. Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 What is a Village Place Plan? Nexus Planning (‘Nexus’) was appointed by Trafford Council The Place Plan is a working document that has been in 2019, working alongside technical consultants WSP, developed through a process of engagement with the local Gillespies and Buttress Architects, to prepare a Place Plan for community. Indeed, the community is very much at the heart Hale village centre. of this plan, and without their input, we would be unable to create a plan which really understands the needs and desires Hale village centre is situated less than 1km to the south east of those who live in and surrounding the village, and those of Altrincham town centre. It is located in Trafford Borough’s who run and own businesses in the village. In this context, administrative area and is one of the designated district the plan sets out the key issues, concerns and priorities centres within the Council’s adopted Core Strategy. people wish to see addressed in order to improve the quality of life within the local area. The Hale Village Place Plan is intended to outline how the village can best serve its residents and businesses through The Hale Village Place Plan includes actions needed to build the creation of a strategy that will provide clarity and upon the unique strengths and distinctive qualities the area confidence to attract future investment.