Reading Sexualized Violence Against Enslaved Males in U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American Poetry As, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “Benefi T” Readings, 1137–138 Abolitionism

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00336-1 - The Cambridge History of: American Poetry Edited by Alfred Bendixen and Stephen Burt Index More information Index “A” (Zukofsky), 736–37 , 742–43 Asian American poetry as, 987–88 “ABC” (Justice), 809–11 “benefi t” readings, 1137–138 abolitionism. See also slavery multilingual poetry and, 1133–134 in African American poetry, 293–95 , 324 Adam, Helen, 823–24 in Longfellow’s poetry, 241–42 , 249–52 Adams, Charles Follen, 468 in mid-nineteenth-century poetry, Adams, Charles Frances, 468 290–95 Adams, John, 140 , 148–49 in Whittier’s poetry, 261–67 Adams, L é onie, 645 , 1012–1013 in women’s poetry, 185–86 , 290–95 Adcock, Betty, 811–13 , 814 Abraham Lincoln: An Horatian Ode “Address to James Oglethorpe, An” (Stoddard), 405 (Kirkpatrick), 122–23 Abrams, M. H., 1003–1004 , 1098 “Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, academic verse Ethiopian Poetess, Who Came literary canon and, 2 from Africa at Eight Year of Age, southern poetry and infl uence of, 795–96 and Soon Became Acquainted with Academy for Negro Youth (Baltimore), the Gospel of Jesus Christ, An” 293–95 (Hammon), 138–39 “Academy in Peril: William Carlos “Adieu to Norman, Bonjour to Joan and Williams Meets the MLA, The” Jean-Paul” (O’Hara), 858–60 (Bernstein), 571–72 Admirable Crichton, The (Barrie), Academy of American Poets, 856–64 , 790–91 1135–136 Admonitions (Spicer), 836–37 Bishop’s fellowship from, 775 Adoff , Arnold, 1118 prize to Moss by, 1032 “Adonais” (Shelley), 88–90 Acadians, poetry about, 37–38 , 241–42 , Adorno, Theodor, 863 , 1042–1043 252–54 , 264–65 Adulateur, The (Warren), 134–35 Accent (television show), 1113–115 Adventure (Bryher), 613–14 “Accountability” (Dunbar), 394 Adventures of Daniel Boone, The (Bryan), Ackerman, Diane, 932–33 157–58 Á coma people, in Spanish epic Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Twain), poetry, 49–50 183–86 Active Anthology (Pound), 679 funeral elegy ridiculed in, 102–04 activist poetry. -

Lyrical Liberators Contents

LYRICAL LIBERATORS CONTENTS List of Illustrations xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1. Calls for Action 18 2. The Murder of Elijah P. Lovejoy 41 3. Fugitive Slaves 47 4. The Assault on Senator Charles Sumner 108 5. John Brown and the Raid on Harpers Ferry 116 6. Slaves and Death 136 7. Slave Mothers 156 8. The South 170 9. Equality 213 10. Freedom 226 11. Atonement 252 12. Wartime 289 13. Emancipation, the Proclamation, and the Thirteenth Amendment 325 Notes 345 Works Cited 353 General Index 359 Index of Poem Titles 367 Index of Poets 371 xi INTRODUCTION he problematic issue of slavery would appear not to lend itself to po- etry, yet in truth nothing would have seemed more natural to nineteenth- T century Americans. Poetry meant many different things at the time—it was at once art form, popular entertainment, instructional medium, and forum for sociopolitical commentary. The poems that appeared in periodicals of the era are therefore integral to our understanding of how the populace felt about any issue of consequence. Writers seized on this uniquely persuasive genre to win readers over to their cause, and perhaps most memorable among them are the abolitionists. Antislavery activists turned to poetry so as to connect both emotionally and rationally with a wide audience on a regular basis. By speaking out on behalf of those who could not speak for themselves, their poems were one of the most effective means of bearing witness to, and thus also protesting, a reprehensible institution. These pleas for justice proved ef- fective by insisting on the right of freedom of speech at a time when it ap- peared to be in jeopardy. -

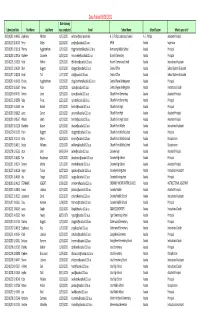

Data Pulled 03/03/2021

Data Pulled 03/03/2021 Date training Submission Date First Name Last Name was completed Email School Name School System What is your role? 2020/10/15 14:44:35 Stephanie Whitten 10/15/2020 [email protected] A. E. Phillips Laboratory School A. E. Phillips Assistant Principal 2020/10/29 11:00:43 Perry Myles 10/20/2020 [email protected] APSB Acadia Supervisor 2020/10/19 12:02:18 Theresa Higginbotham 10/19/2020 [email protected] Armstrong Middle School Acadia Principal 2020/10/19 12:09:16 Marlene Courvelle 10/19/2020 [email protected] Branch Elementary Acadia Principal 2020/10/23 13:28:20 Holly Vidrine 10/23/2020 [email protected] Branch Elementary School Acadia Instructional Assistant 2020/10/23 12:42:50 Ellan Baggett 10/23/2020 [email protected] Central Office Acadia School Systems Evaluator 2020/11/17 12:00:28 Carol Tall 11/17/2020 [email protected] Central Office Acadia School Systems Evaluator 2020/10/19 14:14:39 Christy Higginbotham 10/19/2020 [email protected] Central Rayne Kindergarten Acadia Principal 2020/10/20 15:35:47 Renee Patin 10/20/2020 [email protected] Central Rayne Kindergarten Acadia Instructional Coach 2020/10/19 09:47:51 Timmy Jones 10/19/2020 [email protected] Church Point Elementary Acadia Assistant Principal 2020/10/21 19:18:56 Ruby Privat 10/21/2020 [email protected] Church Point Elementary Acadia Principal 2020/10/19 14:26:33 Lee Bellard 10/19/2020 [email protected] Church Point High Acadia Principal 2020/10/19 10:18:29 -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ■UMIAccessing the Worlds Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8726748 Black 'women abolitionists: A study of gender and race in the American antislavery movement, 1828-1800 Yee, Shirley Jo>ann, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1987 Copyright ©1987 by Yee, Shirley Jo-ann. All rights reserved. UMI 300N. ZeebRd. Ann Aibor, MI 48106 BLACK WOMEN ABOLITIONISTS: A STUDY OF GENDER AND RACE IN THE AMERICAN ANTISLAVERY MOVEMENT, 1828-1860 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Shirley Jo-ann Yee, A.B., M.A * * * * * The Ohio State University 1987 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. -

Competency-Based Word Processing (Grade Levels 9-12). Bulletin No

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 229 627 CE 035 991 TITLE Competency-Based Word Processing (Grade Levels 9-12). Bulletin No. 1699. INSTITUTION Louisiana State Dept. of Education, Baton Rouge. Div. of Vocational Education. PUB DATE [82] NOTE 421p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides' (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; Career Education; Clerical Occupations; Communication Skills; *Competence; Competency Based Education; Editing; Educational Resources; High Schools; Human Relations; *Job Skills; Learning Activities; Office Machines; Office Occupations; *Office Occupations Education; Recordkeeping; Secretaries; State Curriculum Guides; Teaching Methods; Test Items; Transparencies; Vocational Education; *Word Processing IDENTIFIERS Louisiana ABSTRACT The 13 units in this curriculum guide are intended to aid business teachers in Louisiana high schools toprepare students to obtain entry-level employment in word-processing occupations. The first nine units cover the following topics: basic concepts of word processing, career opportunities, human relations skills, clerical skills, communication skills, equipment-related skills, machine dictation and transcription, proofreading and editing, and records management and reprographics. Four additional units include objectives and activities that will provide students withan opportunity to learn to operate equipment and to developa marketable skill in producing various documents with word processing equipment. Each unit contains an introduction to the subject -

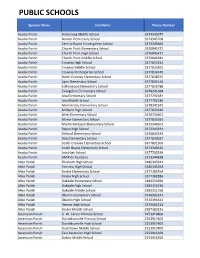

Public Schools

PUBLIC SCHOOLS Sponsor Name Site Name Phone Number Acadia Parish Armstrong Middle School 3373343377 Acadia Parish Branch Elementary School 3373345708 Acadia Parish Central Rayne Kindergarten School 3373343669 Acadia Parish Church Point Elementary School 3376845722 Acadia Parish Church Point High School 3376845472 Acadia Parish Church Point Middle School 3376846381 Acadia Parish Crowley High School 3377835313 Acadia Parish Crowley Middle School 3377835305 Acadia Parish Crowley Kindergarten School 3377834670 Acadia Parish North Crowley Elementary School 3377838755 Acadia Parish Egan Elementary School 3377834148 Acadia Parish Estherwood Elementary School 3377836788 Acadia Parish Evangeline Elementary School 3378241368 Acadia Parish Iota Elementary School 3377792581 Acadia Parish Iota Middle School 3377792536 Acadia Parish Mermentau Elementary School 3378241943 Acadia Parish Midland High School 3377833310 Acadia Parish Mire Elementary School 3378736602 Acadia Parish Morse Elementary School 3377835391 Acadia Parish Martin Petitjean Elementary School 3373349501 Acadia Parish Rayne High School 3373343691 Acadia Parish Richard Elementary School 3376843339 Acadia Parish Ross Elementary School 3377830927 Acadia Parish South Crowley Elementary School 3377831300 Acadia Parish South Rayne Elementary School 3373343610 Acadia Parish Iota High School 3377792534 Acadia Parish AMIKids Acadiana 3373344838 Allen Parish Elizabeth High School 3186345341 Allen Parish Fairview High School 3186345354 Allen Parish Kinder Elementary School 3377382454 Allen Parish -

Socioeconomic Impacts of Salt Marsh Die Back CEI Project 21-19 Historical Places

Socioeconomic Impacts of Salt Marsh Die Back CEI Project 21-19 Historical Places Date Placed Historic Name Other Names City Parish on Register Jefferson Parish Barataria Unit Historic District, Jean Lafitte Barataria Unit Historic District National Park Barataria Jefferson 5/11/1989 1 Bernard, L. J. Hardware Store Westwego Jefferson 9/22/2000 1 Buchler, Conrad A. House Westwego Jefferson 9/9/1999 1 Camp Parapet Powder Magazine Metarie Jefferson 5/24/1977 1 David Crockett Fire Company Hall and David Crockett Fire Company Gould #31 Pumper Gould #31 and Fire Hall Gretna Jefferson 1/27/1983 1 Felix-Block Building Kenner Jefferson 7/18/1985 1 Fort Livingston Grand Terre Island Jefferson 8/30/1974 1 Gretna Historic District Gretna Jefferson 5/2/1985 1 Harahan Elementary School Harahan Jefferson 4/14/1983 1 Kenner Town Hall Kenner Jefferson 1/23/1986 1 Kerner House Gretna Jefferson 1/28/2000 1 Magnolia Lane Plantation House Westwego Jefferson 2/13/1986 1 Martin, Ed seafood Company factory and Home Westwego Jefferson 9/29/2000 1 Old Jefferson Parish Courthouse Gretna City Hall Gretna Jefferson 1/21/1983 1 Pitre, Vic House Westwego Jefferson 8/20/1998 1 Raziano House Mahogany Manor Kenner Jefferson 8/14/1998 1 So. Pacific Steam Locomotive # 745 Jefferson Jefferson 9/4/1998 1 St. Joseph Church - Convent of the Most Holy St. Joseph Church Sacrament Complex Gretna Jefferson 4/15/1983 1 18 Total Socioeconomic Impacts of Salt Marsh Die Back CEI Project 21-19 Historical Places Date Placed Historic Name Other Names City Parish on Register Lafourche Parish -

The Non-Professional Theatre in Louisiana, 1900-1925

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 The on-PN rofessional Theatre in Louisiana, 1900-1925. George Craft rB ian Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Brian, George Craft, "The on-PN rofessional Theatre in Louisiana, 1900-1925." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1006. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1006 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65-6403 microfilmed exactly as received BRIAN, George Craft, 1919- THE NON-PROFESSIONAL THEATRE IN LOUISIANA, 1900-1925. Louisiana State University,, Ph. D ., 1965 Speech-Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HON-PROFESSIONAL THEATRE IN LOUISIANA 1900 - 1925 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Speech by George Craft Brian B.A., Louisiana State University, 1947 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1951 January, 1965 LOUISIANA 1 NORTH LOUISIANA ZA SOUTHWEST LOUISIANA ; sn St t/tpcm Z B SOUTH CENTRAL LOUISIANA BAYOU COUNTRY 3 SOUTHEAST LOUISIANA FLORIDA 'PARISHES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to acknowledge the able direction of Dr. Clinton W. Bradford in the preparation of this work. He appre- elates the assistance of Dr. -

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow At

on fellow ous L g ulletinH e Volume No. A Newsletter of the Friends of the Longfellow House and the National Park Service December pecial nniversary ssue House SelectedB As Part of Underground Railroad Network to Freedom S Henry WadsworthA LongfellowI he Longfellow National Historic Site apply for grants dedicated to Underground Turns 200 Thas been awarded status as a research Railroad preservation and research. ebruary , , marks the th facility with the Na- This new national Fanniversary of the birth of America’s tional Park Service’s Network also seeks first renowned poet, Henry Wadsworth Underground Railroad to foster communi- Longfellow. Throughout the coming year, Network to Freedom cation between re- Longfellow NHS, Harvard University, (NTF) program. This searchers and inter- Mount Auburn Cemetery, and the Maine program serves to coor- ested parties, and to Historical Society will collaborate on dinate preservation and help develop state- exhibits and events to observe the occa- education efforts na- wide organizations sion. (See related articles on page .) tionwide and link a for preserving and On February the Longfellow House multitude of historic sites, museums, and researching Underground Railroad sites. and Mount Auburn Cemetery will hold interpretive programs connected to various Robert Fudge, the Chief of Interpreta- their annual birthday celebration, for the facets of the Underground Railroad. tion and Education for the Northeast first time with the theme of Henry Long- This honor will allow the LNHS to dis- Region of the NPS, announced the selec- fellow’s connections to abolitionism. Both play the Network sign with its logo, receive tion of the Longfellow NHS for the Un- historic places will announce their new technical assistance, and participate in pro- derground Railroad Network to Freedom status as part of the NTF. -

BOOKS" to 9840398093

PRICE OF THIS BOOK is Rs.350 PDF COPY IS Rs.200 For Details, Whatsapp "BOOKS" to 9840398093 RADIAN IAS ACADEMY (CHENNAI - 9840400825 MADURAI - 9840398093) www.radianiasacademy.org -3- PART-C 9. Match the following Folk Arts with the Indian AUTHORS AND THEIR LITERARY WORKS State / Country 10. Match the Author with the Relevant 1.Match the Poems with the Poets Title/Character A Psalm of Life - Be the Best - The cry of the children - 11. Match the Characters with Relevant Story Title The Piano – Manliness Going for water – Earth -The Apology - Be Glad your Nose is on your face - The The Selfish Giant - How the camel got its hump - The Lottery ticket - The Last Leaf - Two friends – Refugee - Flying Wonder -Is Life But a Dream - Be the Best - O Open window – Reflowering - The Necklace Holiday captain My Captain - Snake - Punishment in Kindergarten -Where the Mind is Without fear - The Man 12. About the Poets Rabindranath Tagore - Henry Wordsworth Longfellow - He Killed - Nine Gold Medals Anne Louisa Walker -V K Gokak - Walt Whitman - 2.Which Nationality the story belongs to? Douglas Malloch The selfish Giant - The Lottery Ticket - The Last Leaf - How the Camel got its Hump - Two Friends – Refugee - 13. About the Dramatists William Shakespeare - Thomas Hardy The Open Window 14. Mention the Poem in which these lines occur 3.Identify the Author with the short story The selfish Giant - The Lottery Ticket - The Last Leaf - Granny, Granny, please comb My Hair - With a friend - To cook and Eat - To India – My Native Land - A tiger in How the Camel got its Hump - Two Friends – Refugee - the Zoo - No men are foreign – Laugh and be Merry – The Open Window - A Man who Had no Eyes - The The Apology - The Flying Wonder Tears of the Desert – Sam The Piano - The face of 15. -

Authors and Friends

Authors and Friends Annie Fields The Project Gutenberg EBook of Authors and Friends, by Annie Fields Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Authors and Friends Author: Annie Fields Release Date: August, 2005 [EBook #8777] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on August 12, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO Latin-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AUTHORS AND FRIENDS *** Produced by Tiffany Vergon, Patricia Ehler and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. AUTHORS AND FRIENDS by ANNIE FIELDS '"The Company of the Leaf" wore laurel chaplets "whose lusty green may not appaired be." They represent the brave and steadfast of all ages, the great knights and champions, the constant lovers and pure women of past and present times.' Keping beautie fresh and greene For there nis storme that ne may hem deface. -

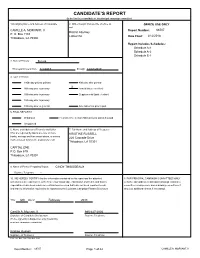

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well CAMILLE A. MORVANT, II Report Number: 68707 District Attorney P. O. Box 1103 Lafourche Date Filed: 2/12/2018 Thibodaux, LA 70302 Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule E-1 3. Date of Primary Future This report covers from 1/1/2017 through 12/31/2017 4. Type of Report: 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general X 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more KRISTINE RUSSELL banks, savings and loan associations, or money 226 Cascade Drive market mutual fund as the depository of all Thibodaux, LA 70301 CAPITAL ONE P.O. Box 819 Thibodaux, LA 70301 9. Name of Person Preparing Report CINDY THIBODEAUX Daytime Telephone -- 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. Name and address of principal campaign committee, expenditures have been made nor contributions received that have not been reported herein, committee’s chairperson, and subsidiary committees, if and that no information required to be reported by the Louisiana Campaign Finance Disclosure any (use additional sheets if necessary).