Utopia – Notes From: Sargent, Lyman Tower; UTOPIANISM – a Very Short Introduction; OXFORD, Univ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questioning Identity, Humanity and Culture Through Japanese Anime

The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan The Many Faces of Popular Culture and Contemporary Processes: Questioning Identity, Humanity and Culture through Japanese Anime Mateja Kovacic Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong 0434 The Asian Conference on Arts & Humanities 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract In a highly globalized world we live in, popular culture bears a very distinctive role: it becomes a global medium for borderless questioning of ourselves and our identities as well as our humanity in an ever-transforming environment which requires us to be constantly ''plugged in'' in order to respond to all the challenges as best as we can. Vast cultural products we create and consume every day thus provide a relevant insight into problems that both researchers and audiences have to face with in an informatised and technologised world. Japanese anime is one of such cultural products: a locally produced cultural artifact became a global phenomenon that transcends cultures and spaces. In its imageries we discover a wide range of themes that concern us today, ranging from bioethical issues, such as ecological crisis, posthumanism and loss of identity in a highly transforming world to the issues of traditionality and spirituality. The author will show in what ways we can approach and study popular culture products in order to understand the anxieties and prevailing concerns of our cultures today, with emphasis on the identity and humanity, and their position in the contemporary high-tech world we live in. The author's intention is to point to popular culture as a significant (re)source for the fields of humanities and cultural studies, as well as for discussing human transformations and possible future outcomes of these transformations in a technoscientific world. -

1: for Me, It Was Personal Names with Too Many of the Letter "Q"

1: For me, it was personal names with too many of the letter "q", "z", or "x". With apostrophes. Big indicator of "call a rabbit a smeerp"; and generally, a given name turns up on page 1... 2: Large scale conspiracies over large time scales that remain secret and don't fall apart. (This is not *explicitly* limited to SF, but appears more often in branded-cyberpunk than one would hope for a subgenre borne out of Bruce Sterling being politically realistic in a zine.) Pretty much *any* form of large-scale space travel. Low earth orbit, not so much; but, human beings in tin cans going to other planets within the solar system is an expensive multi-year endevour that is unlikely to be done on a more regular basis than people went back and forth between Europe and the americas prior to steam ships. Forget about interstellar travel. Any variation on the old chestnut of "robots/ais can't be emotional/creative". On the one hand, this is realistic because human beings have a tendency for othering other races with beliefs and assumptions that don't hold up to any kind of scrutiny (see, for instance, the relatively common belief in pre-1850 US that black people literally couldn't feel pain). On the other hand, we're nowhere near AGI right now and it's already obvious to everyone with even limited experience that AI can be creative (nothing is more creative than a PRNG) and emotional (since emotions are the least complex and most mechanical part of human experience and thus are easy to simulate). -

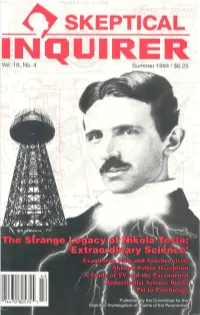

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol

SKEPTICAL INQUIRER Vol. 18. No. 4 THE SKEPTICAL INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, an international organization. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board James E. Alcock, Barry Beyerstein, Susan J. Blackmore, Martin Gardner, Ray Hyman, Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, Joe Nickell, Lee Nisbet, Bela Scheiber. Consulting Editors Robert A. Baker, William Sims Bainbridge, John R. Cole, Kenneth L. Feder, C. E. M. Hansel, E. C. Krupp, David F. Marks, Andrew Neher, James E. Oberg, Robert Sheaffer, Steven N. Shore. Managing Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Contributing Editor Lys Ann Shore. Writer Intern Thomas C. Genoni, Jr. Cartoonist Rob Pudim. Business Manager Mary Rose Hays. Assistant Business Manager Sandra Lesniak. Chief Data Officer Richard Seymour. Fulfillment Manager Michael Cione. Production Paul E. Loynes. Art Linda Hays. Audio Technician Vance Vigrass. Librarian Jonathan Jiras. Staff Alfreda Pidgeon, Etienne C. Rios, Ranjit Sandhu, Sharon Sikora, Elizabeth Begley (Albuquerque). The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo. Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director. Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director. Fellows of the Committee James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky; Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada; Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern California; Susan Blackmore,* psychologist, Univ. of the West of England, Bristol; Henri Broch, physicist, Univ. of Nice, France; Jan Harold Brunvand, folklorist, professor of English, Univ. -

Worldcon 2008 2 Editorial

No. 101 WORLDCON 2008 2 EDITORIAL Dear reader, "Parsek" is the oldest Croatian fanzine, first published in 1977 as the Aleksandar Žiljak bulletin of Science Fiction Club SFera from Fluffy 3 Zagreb. Today, SFera consists of some two Veronika Santo hundred members and is a literary society, The Heart of the Beast 8 as well as being a fan club. The annual Zvonko Bednjanec SFeraKon conventions attract hundreds of The Ninth Duck 11 fans, while prestigious SFERA Award is Milena Benini being given in several categories. You will The Circus Has Come 15 also notice that many authors represented Dario Rukavina here are SFERA Award winners. A Passage to the East 23 Now, let me introduce you to the Živko Prodanović Croatian SF, with the little help of SFERA's SF haiku 28 official mascot, Bemmet. Aleksandar Žiljak Science Fiction in Croatia 29 Enjoy! SFeraKon GoHs They Said on Croatia… 43 Boris Švel Dalibor Perković and Boris Švel SF Conventions in Croatia 46 In Zagreb, 31st July 2008 NOTE: all materials are translated by the "Parsek" on net: authors themselves, unless stated otherwise http://parsek.sfera.hr/ " and: http://parsek.blog.hr/ PARSEK is bulletin of SFera, Društvo za znanstvenu fantastiku, IV. Podbrežje 5, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia. Editor and designer: Boris Švel. All materials are translated by the authors themselves, unless stated otherwise. Proof- reader: Aleksandar Žiljak. Cover: Darko Macan. All rights reserved. 3 Being one of the foremost Croatian SF authors, Aleksandar Žiljak was born in 1963 and resides in Zagreb. He won SFERA Award six times, equally excelling in illustration and prose, as well as the editorial work, being the co-editor of the new Croatian SF literary magazine UBIQ. -

Translation from Croatian to English

Translation from Croatian to English Šimek, Iva Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2015 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Rijeci, Filozofski fakultet u Rijeci Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:186:036907 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences - FHSSRI Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Iva Šimek TRANSLATION FROM CROATIAN INTO ENGLISH TRANSLATION AND ANALYSIS OF TEXTS OF DIFFERENT GENRES Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the B.A. in English Language and Literature and Pedagogy at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Nikola Tutek B.A. Abstract The main idea behind this thesis is to demonstrate the most frequent errors and problems which might occur during the process of translation. For the purposes of the most detailed and in depth analysis of the texts which are to be approached, their genres differentiate. First text tackles the issues with regard to education. Second text deals with the topic of gender roles, while the third and the final text is the interview with one of the most famous SF authors in Croatia. Each sectionstarts with the original source which is followed by the translation and the already mentioned analysis by the means of Genre Analysis, taken from the Postgraduate Studies of Specialized English Translation and Interpreting at the Budapest University of Technology and Economy. The analysis includes: genre, source, audience, purpose of writing, authenticity, style, level of formality, layout, lenght and content. -

Download Kontakt: an Anthology of Croatian SF PDF

Download: Kontakt: An Anthology of Croatian SF PDF Free [518.Book] Download Kontakt: An Anthology of Croatian SF PDF By Zoran Vlahovi?, Milena Benini, Aleksandar Žiljak Kontakt: An Anthology of Croatian SF you can download free book and read Kontakt: An Anthology of Croatian SF for free here. Do you want to search free download Kontakt: An Anthology of Croatian SF or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Kontakt: An Anthology of Croatian SF | #1337428 in eBooks | 2014-02-11 | 2014-02-11 | File type: PDF | |1 of 1 people found the following review helpful.| Intro to Croatian SF/fantasy | By Edward Bosnar |The community of Croatian science fiction and fantasy writers has deserved a nice introductory foreign-language anthology like this for a long time. The writers whose works are encompassed by the anthology are truly a cross-section of the finest Croatia has to offer, and the stories range from straight-up science fiction to fantasy, The original paperback edition of Kontakt was produced in conjunction with the 2012 the European Science Fiction Convention (Eurocon) in Zagreb, and given away free to members. It has never been generally available for sale. All of the stories in it are translated into English, with the intention of showcasing Croatian science fiction and fantasy fiction to the wider world. Of the twelve stories in the book, two have already achieved recognition outside of Cro [630.Book] -

SIEF Congresses

Zagreb 12th Congress, 21-25 June 2015 Timetable Sun June 21 Mon June 22 Tue June 23 Wed June 24 Thu June 25 08:45- 09:45 Keynote 2 Keynote 3 Keynote 4 09:45-10:00 Getting from Keynote to main venue 10:00-10:30 Refreshments Refreshments Refreshments 10:30-12:00 Panel session 1 Panel session 4 Panel session 7 12:00-14:00 Lunch Lunch Lunch 14:00-15:30 Panel session 2 Panel session 5 Panel session 8 Excursions 15:30-16:00 Refreshments Refreshments Refreshments Registration 16:00-17:30 Panel session 3 Panel session 6 Panel session 9 17:30-17:50 Break Break Break Young Scholar Working group 17:50-18:50 Prize & meetings Closing Opening and presentation roundtable Keynote 1 (ends 19:20) 18:50-19:00 (start 18:00) Break Break 19:00-19.30 YS Wine Mixer Journal launch General Assembly 19:30-20:00 Coord meeting of Welcome reception Uni Deps 20:00-21:00 Banquet (starts 20:30) 21:00-22:30 22:30-00:00 Final Party SIEF2015 Utopias, Realities, Heritages: Ethnographies for the 21st Century 12th Congress of Société Internationale d’Ethnologie et de Folklore (SIEF) Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb 21-25 June 2015 Acknowledgements SIEF Board: Pertti Anttonen, Jasna Čapo, Tine Damsholt, Laurent Fournier, Valdimar Hafstein, Peter Jan Margry, Arzu Öztürkmen, Clara Saraiva, Monique Scheer SIEF2015 Congress convenors: Jasna Čapo and Nevena Škrbić Alempijević SIEF2015 Scientific Committee:Jasna Čapo, Laurent Fournier, Valdimar Hafstein, Peter Jan Margry, Sanja Potkonjak, Clara Saraiva, -

Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture

University of Alberta The Steampunk Aesthetic: Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture by Mike Dieter Perschon A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature © Mike Dieter Perschon Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Dedicated to Jenica, Gunnar, and Dacy Abstract Despite its growing popularity in books, film, games, fashion, and décor, a suitable definition for steampunk remains elusive. Debates in online forums seek to arrive at a cogent definition, ranging from narrowly restricting and exclusionary definitions, to uselessly inclusive indefinitions. The difficulty in defining steampunk stems from the evolution of the term as a literary sub-genre of science fiction (SF) to a sub-culture of Goth fashion, Do-It-Yourself (DIY) arts and crafts movements, and more recently, as ideological counter-culture. Accordingly, defining steampunk unilaterally is challenged by what aspect of steampunk culture is being defined. -

(2018) Sci-Fi Live

nglish anguage verseas erspectives and nquiries Vol. 15, No. 1 (2018) Sci-Fi Live Editor of ELOPE Vol. 15, No. 1: MOJCA KRevel Journal Editors: SMILJANA KOMAR and MOJCA KRevel Ljubljana University Press, Faculty of Arts Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Ljubljana, 2018 ISSN 1581-8918 nglish anguage verseas erspectives and nquiries Vol. 15, No. 1 (2018) Sci-Fi Live Editor of ELOPE Vol. 15, No. 1: MOJCA KRevel Journal Editors: SMILJANA KOMAR and MOJCA KRevel Ljubljana University Press, Faculty of Arts Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani Ljubljana, 2018 CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 811.111'243(082) 37.091.3:81'243(082) SCI-Fi live / editor Mojca Krevel. - Ljubljana : University Press, Faculty of Arts = Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete, 2018. - (ELOPE : English language overseas perspectives and enquiries, ISSN 1581-8918 ; vol. 15) ISBN 978-961-06-0080-0 1. Krevel, Mojca 295482624 Contents PART I: ARTICLES Mojca Krevel 9 On the Apocalypse that No One Noticed Michelle Gadpaille 17 Sci-fi, Cli-fi or Speculative Fiction: Genre and Discourse in Margaret Atwood’s “Three Novels I Won’t Write Soon” Znanstvena fantastika, klimatska fantastika ali spekulativna fikcija: žanr in diskurz v »Three Novels I Won’t Write Soon« Margaret Atwood Victor Kennedy 29 The Gravity of Cartoon Physics; or, Schrödinger’s Coyote Gravitacija v fiziki risank; ali Schrödingerjev kojot Anamarija Šporčič 51 The (Ir)Relevance of Science Fiction to Non-Binary and Genderqueer Readers (I)relevantnost znanstvene fantastike za nebinarno in kvirovsko bralstvo Antonia Leach 69 Iain M. Banks – Human, Posthuman and Beyond Human Iain M. -

Films from Around the World

27 November - 6 December berlinscifi.com facebook.com/berlinscifi twitter.com/BScifi/ 20 instagram.com/berlinscififilmfest s a t l Virtual Theatre at a B s i r xerb.tv/channel/berlinscififilmfest/virtual-events A h t i w International Online Film Festival m o c . s a r t i s t s o g r o i g . w 20w w Sponsors of the BERLIN SCI-FI FILMFEST redgiant.com newbluefx.com borisfx.com babylonberlin.eu Xerb.tv autodcp.com _________________________________ 1 INTRODUCTION Greetings to you and welcome to Berlin Sci-fi Filmfest, The current COVID-19 regulations have affected the leisure and entertainment industry, not only in German but around the world. What this means, is that the Babylon Cinema (our partners in creating Berlin Sci-fi Filmfest) have had to close and will probably not re-open until the New Year. We are optimistic that they will re-open and the festival once again will take place on the big screen next year. The Berlin Sci-fi Filmfest will continue though with an online international virtual theatre experience via XERB.TV. It will take place from 27th November to 6th December we are offering a mouth-watering program of independent short and feature films from around the world. In fact, we have 110 films from 28 countries over 20 sessions. No need to be bored during the lockdown, that’s for sure! For the 4th year, we have upgraded and tweaked our award once more. The winners, runner-ups and finalists will be announced on Sunday 29th November. -

Eurocon 2011 2 Editorial

No. 1 17 EUROCON 2011 2 EDITORIAL Dear reader, "Parsek" is the oldest Croatian fanzine, first published in 1977 and still Table of content: running. It is also the bulletin of Science Aleksandar Žiljak Fiction Club SFera from Zagreb. Today, The Exterminator 3 SFera consists of some two hundred Milena Benini members and is a literary society, as well as Dancing Together Under Polarized Skies 7 a fan club. The annual SFeraKon Tatjana Jambrišak convention, organized by SFera, attracts Awake Among the Stars 17 nearly a thousand fans each year, and the Ivana Delač SFERA Award (I know, the spelling bothers Reminiscences of a Married Elf 23 me, too) is awarded in several categories. Adnadin Jašarević Now, let me introduce you to the Croatian Oh, My God! 26 SF, with the little help of SFera's cute (oh, Oliver Franić well) official mascot, Bemmet. Araton (fragment of a novel) 28 Ian McDonald Enjoy! Thank you, Maggie (interview) 34 SFeraKon GoHs Boris Švel They Said on Croatia 37 Dalibor Perković and Boris Švel In Zagreb, 10 th June 2011 Croatian SF Conventions 42 "Parsek" on the internet: http://parsek.sfera.hr/ NOTE: all materials are translated by the authors and : themselves, unless stated otherwise. http://parsek.blog.hr/ PARSEK is bulletin of SFera, Društvo za znanstvenu fantastiku, IV. Podbrežje 5, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia. Editor and designer: Boris Švel. Proof-reader: Aleksandar Žiljak. Cover: Professor Baltazar. All rights reserved. 3 One of the foremost Croatian SF authors, Aleksandar Žiljak was born in 1963 and resides in Zagreb. He won SFERA Award six times, equally excelling in illustration and prose, as well as the editorial work, being the co-editor of the new Croatian SF literary magazine UBIQ . -

5 Books from Croatia

5 BOOKS FROM CROATIA 2016 Croatian Writers Society 5 BOOKS FROM CROATIA 5 BOOKS FROM CROATIA 2016 EDITION 1 5 BOOKS FROM CROATIA 2 CONTENT DEAR READERS 5 INTERVIEW WITH OLJA SAVIČEVIĆ IVANČEVIĆ 9 INTERVIEW WITH TONY WHITE 15 CROATIAN LITERARY FESTIVALS 21 USEFUL INFORMATION 25 5 Sibila Petlevski: We Had It So Nice! BOOKS 29 FROM Kristian Novak: Dark Mother Earth CROATIA 45 Marko Dejanović: Tickets, Please! 61 Milena Benini: Da En 81 FORGOTTEN GEM Miroslav Krleža: Journey To Russia 101 3 5 BOOKS FROM CROATIA 4 EDITOR’S WORD DEAR READERS The project 5 Books from Croatia is part of a new push to pro- mote Croatian literature in a more methodical and transparent way. ‘Small’ literatures have always been less visible in the En- glish-speaking world, trailing behind translations from German, French and Spanish. To date, English editions of Croatian authors have been the result of individual endeavours and the passion of a small number of translators and publishers with a special interest in translated literature. But while ‘big’ languages have a tradition of systematically promoting books, such as the leading publications 5 10 Books from Holland and New Books in German, Croatian litera- BOOKS ture is still terra incognita to most publishers, editors and the broad reading public. This is hardly surprising because well-translated, FROM representative excerpts from the best Croatian titles are neither cheap nor easy to come by. CROATIA That is why we have decided to launch 5 Books from Croatia – a publication with a clear editorial conception that once per year will present four contemporary authors and one classic, a ‘forgotten gem’.