Joanna Ostrowska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOGAN MARSHALL-GREEN Jewel

Festival de Cannes 2013 Un Certain Regard METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT présente une production Millennium Films en association avec Rabbit Bandini Productions et Lee Caplin/Picture Corporation un film de James Franco AS I LAY DYING James Franco Tim Blake Nelson Danny McBride Logan Marshall-Green Ahna O’Reilly Jim Parrack Beth Grant Brady Permenter Scénario : James Franco, Matt Rager D’après le livre Tandis que j’agonise de William Faulkner Durée : 1h50 Notre nouveau portail est à votre disposition. Inscrivez-vous à l’espace pro pour récupérer le matériel promotionnel du film sur : www.metrofilms.com Distribution : Relations presse : METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT MOONFLEET 29, rue Galilée - 75116 Paris Jérôme Jouneaux, Cédric Landemaine & Tél. 01 56 59 23 25 Mounia Wissinger Fax 01 53 57 84 02 10, rue d’Aumale - 75009 Paris Tél. 01 53 20 01 20 info@metropolitan -films.com cedric [email protected] Programmation : Partenariats et promotion : Tél. 01 56 59 23 25 AGENCE MERCREDI Tél. 01 56 59 66 66 1 L’HISTOIRE Après le décès d’Addie Bundren, son mari et ses cinq enfants entament un long périple à travers le Mississippi pour accompagner la dépouille jusqu’à sa dernière demeure. Anse, le père, et leurs enfants Cash, Darl, Jewel, Dewey Dell et le plus jeune, Vardaman, quittent leur ferme sur une charrette où ils ont placé le cercueil. Chacun d’eux, profondément affecté, vit la mort d’Addie à sa façon. Leur voyage jusqu’à Jefferson, la ville natale de la défunte, sera rempli d’épreuves, imposées par la nature ou le destin. Mais pour ce qu’il reste de cette famille, rien ne sera plus dangereux que les tourments et les blessures secrètes que chacun porte au plus profond de lui… 2 NOTES DE PRODUCTION « Il faut deux personnes pour faire un homme, mais il n’en faut qu’une pour mourir. -

THE ICEMAN Textes DP

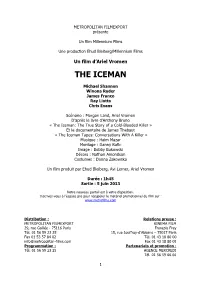

METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT présente Un film Millennium Films Une production Ehud Bleiberg/Millennium Films Un film d’Ariel Vromen THE ICEMAN Michael Shannon Winona Ryder James Franco Ray Liotta Chris Evans Scénario : Morgan Land, Ariel Vromen D’après le livre d’Anthony Bruno « The Iceman: The True Story of a Cold-Blooded Killer » Et le documentaire de James Thebaut « The Iceman Tapes: Conversations With A Killer » Musique : Haim Mazar Montage : Danny Rafic Image : Bobby Bukowski Décors : Nathan Amondson Costumes : Donna Zakowska Un film produit par Ehud Bleiberg, Avi Lerner, Ariel Vromen Durée : 1h45 Sortie : 5 juin 2013 Notre nouveau portail est à votre disposition. Inscrivez-vous à l’espace pro pour récupérer le matériel promotionnel du film sur : www.metrofilms.com Distribution : Relations presse : METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT KINEMA FILM 29, rue Galilée - 75116 Paris François Frey Tél. 01 56 59 23 25 15, rue Jouffroy-d’Abbans – 75017 Paris Fax 01 53 57 84 02 Tél. 01 43 18 80 00 info@metropolitan -films.com Fax 01 43 18 80 09 Programmation : Partenariats et promotion : Tél. 01 56 59 23 25 AGENCE MERCREDI Tél. 01 56 59 66 66 1 L’HISTOIRE Tiré de faits réels, voici l’histoire de Richard Kuklinski, surnommé « The Iceman », un tueur à gages qui fut condamné pour une centaine de meurtres commandités par différentes organisations criminelles new-yorkaises. Menant une double vie pendant plus de vingt ans, ce pur modèle du rêve américain vivait auprès de sa superbe femme, Deborah Pellicotti, et de leurs enfants, tout en étant secrètement un redoutable tueur professionnel. Lorsqu’il fut finalement arrêté par les fédéraux en 1986, ni sa femme, ni ses filles, ni ses proches ne s’étaient douté un seul instant qu’il était un assassin. -

Electric Boogaloo: the Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films

Press Kit ELECTRIC BOOGALOO: THE WILD, UNTOLD STORY OF CANNON FILMS Table Of Contents CONTACT DETAILS And Technical Information 1 SYNOPSIS: LOGLINE AND ONE PARAGRAPH 2 SYNOPSIS: ONE PAGE 3 DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT 4 PRODUCER’S STATEMENT 5 KEY CREATIVE CREDITS 6 DIRECTOR BIOGRAPHY 7 PRODUCER BIOGRAPHY 8 KEY CREATIVEs 10 INTERVIEWEE LIST 11 - 12 SELECT INTERVIEWEE BIOGRAPHIES 13 - 16 FINAL END CREDITS 17 - 34 A CELEBRATION OF HOLLYWOOD’S LEAST LOVED STUDIO FROM THE DIRECTOR OF NOT QUITE HOLLYWOOD RATPAC DOCUMENTARY FILMS WILDBEAR ENTERTAINMENT IN ASSOCIATION WITH MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PREMIERE FUND SCREEN QUEENSLAND FILM VICTORIA AND CELLULOID NIGHTMARES PRESENT ELECTRIC BOOGALOO: THE WILD, UNTOLD STORY OF CANNON FILMS ORIGINAL MUSIC JAMIE BLANKS CINEMATOGRAPHER GARRY RICHARDS EDITED BY MARK HARTLEY SARA EDWARDS JAMIE BLANKS Check the Classification EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS NATE BOLOTIN TODD BROWN JEFF HARRISON HUGH MARKS JAMES PACKER PRODUCED BY BRETT RATNER VERONICA FURY WRITTEN AND DIRECTED BY MARK HARTLEY Press Kit A CELEBRATION OF HOLLYWOOD’S LEAST LOVED STUDIO FROM THE DIRECTOR OF NOT QUITE HOLLYWOOD RATPAC DOCUMENTARY FILMS WILDBEAR ENTERTAINMENT IN ASSOCIATION WITH MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL PREMIERE FUND SCREEN QUEENSLAND FILM VICTORIA AND CELLULOID NIGHTMARES PRESENT ELECTRIC BOOGALOO: THE WILD, UNTOLD STORY OF CANNON FILMS ORIGINAL MUSIC JAMIE BLANKS CINEMATOGRAPHER GARRY RICHARDS EDITED BY MARK HARTLEY SARA EDWARDS JAMIE BLANKS Check the Classification EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS NATE BOLOTIN TODD BROWN JEFF HARRISON -

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment's Screen Media to Bring

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment’s Screen Media to Bring ‘The Outpost’ Back to Theaters for Special Veterans Day Screenings October 15, 2020 Exclusive Screenings in Partnership with Fathom Events of the Never-Before-Seen-Director’s Cut on November 11th and 12th Include Special Introduction by Director Rod Lurie and Veterans Who Participated in the Movie COS COB, Conn., Oct. 15, 2020 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment Inc. (Nasdaq: CSSE), one of the largest operators of streaming advertising-supported video-on-demand (AVOD) networks, today announced that Screen Media and Millennium Media’s military thriller, The Outpost, a true story based on Jake Tapper’s best-selling non-fiction book, The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor, will return to theaters for special screenings in honor of Veterans Day in partnership with Fathom Events. The screenings are scheduled for November 11th and 12th on more than 350 screens nationwide. Theaters will screen the never-before-seen Director’s Cut which will be accompanied by a special introduction from filmmaker Rod Lurie and the veterans who participated in the film. The Outpost quickly shot to #1 on several VOD platforms after its debut on July 3rd, including GooglePlay, Spectrum, Amazon, FandangoNOW and iTunes, and remained in the top spot for three weeks. The Outpost delivered sustained strong performance throughout the summer and resurfaced as #1 on iTunes two weeks ago. The film is “Certified Fresh” on Rotten Tomatoes, with a 92% rating. In this military thriller, a tiny unit of U.S. soldiers, alone at the remote Combat Outpost Keating, located deep in the valley of three mountains in Afghanistan, battles to defend against an overwhelming force of Taliban fighters in a coordinated attack. -

Şirin Payzın

8TL ŞUBAT-MART 2015 ŞUBAT-MART 42. SAYI 22 yıllık birikimin ekrana yansıması ŞiRiN PaYZıN İMZA: “BY ESTİ” JOSEPH M. HEDY SCHİLLİNGER SCHLEİFER 20. Yüzyılda “Bağlantı Rönesans Mucizesi” AH BEYOĞLU, METROPOL VAH BEYOĞLU STİLLERİ RENÉE LEVİ Yolları kesişen Sibel Sergisi YAZAR, BESTECİ, FİLM YAPIMCISI 1 KEMER COUNTRY’DE KEMER COUNTRY’DE KEMER COUNTRY’DE 7 ODA 2 SALON 800 M2 5 ODA 2 SALON 500 M2 ÇOK ŞIK BAKIMLI 5 ODA 2 SALON TAM MÜSTAKİL VİLLA. TAM MÜSTAKİL VİLLA. 450 M2 MÜSTAKİL VİLLA. 5.000.000 USD 3.750.000 USD 3.150.000 USD KEMER COUNTRY’DE KEMERBURGAZ KEMERBURGAZ 6 ODA 1 SALON 450 M2 PANORAMA VİLLALARIN’DA PANORAMA EVLERİ’NDE TAM MÜSTAKİL VİLLA. TAM MÜSTAKİL 6 ODA 2 SALON 5 ODA 2 SALON 350 M2 3.000.000 USD 800 M2 VİLLA. 3.750.000 USD ÇATI DUBLEKSİ. 1.100.000 USD 2 KEMERBURGAZ KEMERBURGAZ KEMER CORNER SİTESİ’NDE ALTINTAŞ EVLERİ’NDE ARKETİP EVLERİ’NDE FERAH 2 ODA 1 SALON 4 ODA 1 SALON 250 M2 VİLLA. KÖŞE KONUMLU 3 ODA 1 SALON 152 M2 BAHÇE KATI. 920.000 USD 185M2 BAHÇE KATI. 475.000 USD 560.000 USD KEMERBURGAZ KEMERBURGAZ KEMERBURGAZ MESA YANKI EVLERİ’NDE ARKETİP EVLERİ’NDE GÖKMAHAL SİTESİ’NDE 2 ODA 1 SALON 110 M2 ARA KAT. BÜYÜK TERASLI PANJURLU 1 ODA 1 SALON +1 HİZMETLİ ODALI 400.000 USD 3 ODA 1 SALON 180 M2 DAİRE. DAİRE 535.000 TL 570.000 USD 3 4 5 Editörden... Sevgili okurlar, Şubat dergimizin kapağındaki hanıme- fendiyi tanımayanınız yoktur her halde. CNN’de gün- demin tartışıldığı “Ne oluyor?” adlı programı ile haftanın birkaç gecesi bizleri ekrana bağlayan Şirin Payzın bu ay Dergi’ye konuk oldu. -

He Wanted to Do Was Go Home and Get a Drink. but at 8:02 Am, Hungover

~ Final Production Information ~ All he wanted to do was go home and get a drink. But at 8:02 a.m., hungover NYPD detective Jack Mosley (BRUCE WILLIS) is assigned a seemingly simple task. Petty criminal Eddie Bunker (MOS DEF) is set to testify before a grand jury at 10:00 a.m. and needs to be taken from lock-up to the courthouse, 16 blocks away. It should take Jack 15 minutes to drop him off at the courthouse and get home. Broken down, out of shape, with a bad leg and a serious drinking problem, Jack’s role on the force is simple – clock in, clock out and stay out of trouble in between. He’s in no mood to deal with a punk who’s been in and out of jail for more than half his life. But beneath the punk in Eddie lies a man committed to turning his life around and constantly searching for “signs” that will lead him to a brighter future. Jack knows better, though – people don’t change. In Eddie he sees only a pathetic rat who was offered a sweet deal... a rat he will be rid of soon enough. When Jack shoves Eddie into the back of his car and pulls out into the morning New York city rush hour, he doesn’t notice the van looming behind them. His head throbbing, and Eddie’s flair for conversation only making it worse, Jack stops off at the local liquor store to pick up some breakfast. As Eddie waits inside the locked car, fuming at getting stuck with Jack as his escort, he’s suddenly faced with a much bigger problem – a loaded gun pointed at his head. -

Un Film De RAPHAEL REBIBO Yediot America JFF Miami (USA) « We’Re Big Fans of AMOR and Feel Great Boca Raton (USA) Pride and Honor Presenting It at Our Festival

Rencontres IFF MJFF PBJFF SDJFF Cinématographiques Los Angeles Miami Palm Beach San Diego de Dijon 2016 2017 2017 2017 2016 MAGORA PRODUCTIONS & TRANSFAX FILM présentent France USA USA USA USA IAC DJFF Cinécroisette RJFF CJFF Cinématec Detroit Cannes 2017 Rochester Columbia New Jersey 2017 2ème Prix du Public 2017 2017 2018 USA France USA USA USA JFF BRJFF GPJFF J&IFF FCIM Saratosa Boca Raton Greater Phoenix Mayerson Montréal Manatee 2018 2018 Cincinnati 2018 2018 USA USA 2018 Canada USA USA Projection spéciale Rencontres IAC Cinematec New Jersey (USA) Cinématographiques de Dijon ARP « This is a story of love, freedom, belief, and « ... The story is short, simple. There are no ethics. The conflict inside the lover, the conflict special effects. The artists are, for me, totally inside the religious father. unknown. And the outcome is amazing. The How much freedom is given to someone to do whole audience was sniffing... what he/she wishes ? May this film live, be seen and prove to the How much do you love someone to fullfill his/ whole world that love exists !...» her desires ?” Danielle Paquet-François Rebibo is not afraid to confront fateful issues in his touching and thought provoking film. » 21240 Talant (France) Ilanit Solomonovich-Habot Un film de RAPHAEL REBIBO Yediot America JFF Miami (USA) « We’re big fans of AMOR and feel great Boca Raton (USA) pride and honor presenting it at our Festival. Wishing you much success and all « We just screened this wonderful film the very best ! » in Boca Raton, FL. It is a very moving and Igor Shteyrenberg powerful film, beautifully written, filmed and Director Miami Jewish Film Festival acted… about very real life issues that many of us will « This beautiful film is moving, important, face as individuals and that we all must face as and will make you look at institutions in your a society. -

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment's Screen Media

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment’s Screen Media Announces the Exclusive Nationwide Cinema Premiere of BLACKBIRD with Fathom Events on September 14th and 15th August 20, 2020 Film Starring Susan Sarandon and Kate Winslet to be Released in Select Theaters and On Demand September 18th COS COB, Conn., Aug. 20, 2020 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment’s (Nasdaq: CSSE) Screen Media announced today that ahead of their limited theatrical and VOD release of Roger Michell’s BLACKBIRD on September 18th, they have partnered with Fathom Events for an exclusive nationwide cinema premiere on September 14th and 15th. Each screening will be accompanied by a special introduction from Mr. Michell and exclusive behind-the-scenes footage. Mr. Michell, having worked extensively for the National Theatre, the Royal Court and the Royal Shakespeare Company directing plays such as “Waste,” “ Landscape with Weapon,” “ Honour,” and “ Blue/Orange,” made his directorial splash with his 1995 adaptation of the Jane Austen novel, Persuasion. He has since directed many beloved films such as My Cousin Rachel, Notting Hill, Venus, The Mother, Tea With the Dames and the upcoming The Duke starring Helen Mirren and Jim Broadbent. He has also just signed on to direct Good Morning, Mr. Mandela based on Zelda la Grange’s bestselling novel. Blackbird stars Susan Sarandon, Kate Winslet, Mia Wasikowska, Sam Neill, Rainn Wilson, Bex Taylor-Klaus, Anson Boon, and Lindsay Duncan and tells the story of Lily (Susan Sarandon) and Paul (Sam Neill) who summon their loved ones to their beach house for one final gathering after Lily decides to end her long battle with ALS on her own terms. -

1980S Retro Film Culture and the Masculinity of Cult

IT'S ALL COMING BACK TO YOU: 1980s RETRO FILM CULTURE AND THE MASCULINITY OF CULT Ryan Collins Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Committee Chair Kevin Heffernan, Committee Member James Martin, Committee Member Eugene Martin, Chair of the Department of Media Arts David Holdeman, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Collins, Ryan. It's All Coming Back to You: 1980s Retro Film Culture and the Masculinity of Cult. Master of Arts (Media Industry and Critical Studies), August 2017, 130 pp., bibliography, 214 titles. The 1980s is a formative decade in American history. America sought to reestablish itself as a global power and to reassert the dominant ideology of white, patriarchal capitalism. Likewise, media producers in the 1980s sought to reassert the dominance of the white, male, muscled body in filmic representations. The identity politics of the 1980s and the depictions of the white, muscled body once prominent in the 1980s have been the site of conservative nostalgia for a young, male-dominated, cult audience that is a subset of a larger cultural trend known as retro film culture. This thesis provides historical context behind the populist 1980s B- action films from Cannon Group, Inc that celebrate violent masculinity in filmic representations with white, male action heroes. Equally important is the revival of VHS collecting and how this 1980s-inspired subculture reinforces white, patriarchal capitalism through the cult films they valorize and their capitalistic trading practices despite their claims of oppositionality against mainstream taste and Hollywood films. -

Boaz Davidson Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Boaz Davidson 电影 串行 (大全) Going Steady https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/going-steady-1003092/actors Private Popsicle https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/private-popsicle-1003094/actors Hot Bubblegum https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hot-bubblegum-1003095/actors Fifty-Fifty https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/fifty-fifty-18191829/actors Going Bananas https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/going-bananas-21869380/actors Charlie Ve'hetzi https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/charlie-ve%27hetzi-2909862/actors Hagiga B'Snuker https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hagiga-b%27snuker-2911381/actors American Cyborg Steel https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/american-cyborg-steel-warrior-3284428/actors Warrior Alex Holeh Ahavah https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/alex-holeh-ahavah-4717193/actors Crazy Camera https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/crazy-camera-52837372/actors Hospital Massacre https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hospital-massacre-5908467/actors Shablul https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shablul-6651287/actors Azit the Paratrooper Dog https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/azit-the-paratrooper-dog-6899592/actors Looking for Lola https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/looking-for-lola-9369537/actors Dutch Treat https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dutch-treat-98113349/actors æœˆçƒ ç‰¹é£ éšŠ https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E6%9C%88%E7%90%83%E7%89%B9%E9%81%A3%E9%9A%8A-1962580/actors https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E7%BE%8E%E5%9C%8B%E6%9C%80%E5%BE%8C%E8%99%95%E5%A5%B3- 美國最後處女 2363955/actors 眉飞色舞 https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E7%9C%89%E9%A3%9E%E8%89%B2%E8%88%9E-5246765/actors é’ æ¾€ç‰©èªž https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E9%9D%92%E6%BE%80%E7%89%A9%E8%AA%9E-946157/actors. -

Independent Film at Hollywood Music in Media Awards

Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment’s THE OUTPOST Wins Outstanding Song – Independent Film at Hollywood Music In Media Awards February 2, 2021 Film also named one of the Top Ten Independent Films of the Year by National Board of Review NEW YORK, Feb. 02, 2021 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment’s THE OUTPOST won “Outstanding Song – Independent Film” at the Hollywood Music in Media Awards this week. The win went to the song “Everybody Cries” written by Rod Lurie, Larry Groupé and Rita Wilson and performed by Rita Wilson. The critically acclaimed film was also named one of the “Top Ten Independent Films” by the 111-year-old prestigious voting group, National Board of Review. Directed by award-winning filmmaker Rod Lurie (The Contender, The Last Castle) and adapted by Oscar-nominated screenwriting duo Paul Tamasy and Eric Johnson (The Fighter) from Jake Tapper’s best-selling nonfiction book The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor, the real-life military thriller stars Scott Eastwood, Caleb Landry Jones, Orlando Bloom, Jack Kesy, Cory Hardrict, Taylor John Smith, Jacob Scipio, and Milo Gibson. Screen Media Ventures, a Chicken Soup for the Soul Entertainment company, released THE OUTPOST on July 3rd and the film quickly shot to #1 on several VOD platforms after its debut, including Amazon, iTunes, GooglePlay, Spectrum and FandangoNOW, where it remained in the #1 spot for three weeks. THE OUTPOST remained at the top of the charts throughout the summer and resurfaced as #1 on iTunes in September. It is “Certified Fresh” on Rotten Tomatoes, with a 92% rating. -

Israeli Identities Through Film”

Israeli Identities 2014 (Dan Chyutin) 1 American University, Spring 2014 , Tue & Fri 11:45am-1pm + Mon screenings 8:10-10:40pm. Instructor: Dan Chyutin Office: TBD Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Tue 1:15-2:15pm and by app’t. About “Israeli Identities through Film” This course will engage the various ways through which the filmic medium has portrayed Israel’s complex matrix of cultural identities. Oscillating between considerations of social history and film aesthetics, the different sessions will address the major factors shaping Israeli culture: war and the demands of battlefield heroism; the trauma of the Holocaust; the Mizrahi- Ashkenazi ethnic divide; the contemporary immigration experience; engagements with the Palestinian Other; gender politics; queer identity and the threat of “pinkwashing”; kibbutz life and the decline of collectivism; and the challenge of Judaism to Israeli secularity. Through our discussions, class participants will gain a more comprehensive perspective on Israeli society than is usually offered in mainstream US media, as well as acquire intimate familiarity with certain milestones of Israeli filmmaking, most of which have rarely been screened outside of Israel’s national borders. Beyond providing a particular body of knowledge, the course will also seek to develop in its participants a set of important skills: critical thinking, which provides the foundation for complex and multi-dimensional arguments; close reading, which carefully teases out the nuances of visual or written texts; contextual research, which situates critical argumentation and textual analysis within a broader socio-cultural framework; and verbal expression, which allows for a clear and persuasive organization of claims both orally and in writing.