In the Virgin Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands Clive Petrovic, Esther Georges and Nancy Woodfield Andy McGowan Great Tobago General introduction The British Virgin Islands comprise more than 60 islands, and the Virgin Islands. These include the globally cays and rocks, with a total land area of approximately 58 threatened Cordia rupicola (CR), Maytenus cymosa (EN) and square miles (150 square km). This archipelago is located Acacia anegadensis (CR). on the Puerto Rican Bank in the north-east Caribbean at A quarter of the 24 reptiles and amphibians identified are approximately 18˚N and 64˚W. The islands once formed a endemic, including the Anegada Rock Iguana Cyclura continuous land mass with the US Virgin Islands and pinguis (CR), which is now restricted to Anegada. Other Puerto Rico, and were isolated only in relatively recent endemics include Anolis ernestwilliamsii, Eleutherodactylus geologic time. With the exception of the limestone island of schwartzi, the Anegada Ground Snake Alsophis portoricensis Anegada, the islands are volcanic in origin and are mostly anegadae, the Virgin Gorda Gecko Sphaerodactylus steep-sided with rugged topographic features and little flat parthenopian, the Virgin Gorda Worm Snake Typlops richardi land, surrounded by coral reefs. naugus, and the Anegada Worm Snake Typlops richardi Situated at the eastern end of the Greater Antilles chain, the catapontus. Other globally threatened reptiles within the islands experience a dry sub-tropical climate dominated by BVI include the Anolis roosevelti (CR) and Epicrates monensis the prevailing north-east trade winds. Maximum summer granti (EN). temperatures reach 31˚C; minimum winter temperatures Habitat alteration during the plantation era and the are 19˚C, and there is an average rainfall of 700 mm per introduction of invasive alien species has had major year with seasonal hurricane events. -

Sandy Point, Green Cay and Buck Island National Wildlife Refuges Comprehensive Conservation Plan

Sandy Point, Green Cay and Buck Island National Wildlife Refuges Comprehensive Conservation Plan U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region September 2010 Sandy Point, Green Cay, and Buck Island National Wildlife Refuges COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN SANDY POINT, GREEN CAY AND BUCK ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGES United States Virgin Islands Caribbean Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia September 2010 Table of Contents iii Sandy Point, Green Cay, and Buck Island National Wildlife Refuges TABLE OF CONTENTS COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 1 I. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Need for the Plan .................................................................................................... 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ...................................................................................................... 3 National Wildlife Refuge System .................................................................................................. 4 Legal and Policy Context ............................................................................................................. -

St. John and Cinnamon Bay

United States Department of A Summary of 20 Years Agriculture Forest Service of Forest Monitoring in Cinnamon Bay Watershed, International Institute St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands of Tropical Forestry General Technical Peter L. Weaver Report IITF–34 Author Peter L. Weaver, Research Forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, Jardín Botánico Sur, 1201 Calle Ceiba, San Juan, PR 00926-1119. Cover photos Top right: The island’s attractive scenery prompted President Eisenhower to authorize the establishment of the Virgin Islands National Park as a sanctuary of natural beauty in 1956. Left: A hiker looks up at large Ceiba trees (Ceiba pentandra) at an interpretative stop on one of the many hiking trails scattered throughout Virgin Islands National Park. Bottom right: Picturesque Cruz Bay Harbor with government house situated on a narrow peninsula. All photos in report by Peter L. Weaver. October 2006 International Institute of Tropical Forestry Jardín Botánico Sur 1201 Calle Ceiba San Juan, PR 00926-1119 A Summary of 20 Years of Forest Monitoring in Cinnamon Bay Watershed, St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands Peter L. Weaver Abstract St. John, and probably the Cnnamon Bay watershed, has a hstory of human use datng to 1700 B.C. The most notable mpacts, however, occurred from 1730 to 1780 when sugar cane and cotton producton peaked on the sland. As agrculture was abandoned, the sland regenerated n secondary forest, and n 1956, the Vrgn Islands Natonal Park was created. From 1983 to 2003, the staff of the Internatonal Insttute of Trop cal Forestry montored 16 plots, stratfied by elevaton and topography, n the Cnnamon Bay watershed. -

Virgin Islands National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Virgin Islands National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2010/226 THIS PAGE: Underwater ecosystems including coral reefs are a primary natural resource at Virgin Islands National Park. National Park Service photograph. ON THE COVER: This view of Trunk Bay shows the steep slopes characteristic of Virgin Islands Na- tional Park. National Park Service photo- graph courtesy Rafe Boulon (Virgin Islands National Park). Virgin Islands National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2010/226 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 July 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received informal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY of the PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 251 BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwole, Richard Levins and Michael D. Byer Issued by THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. July 1981 VIRGIN ISLANDS CULEBRA PUERTO RlCO Fig. 1. Map of the Puerto Rican Island Shelf. Rectangles A - E indicate boundaries of maps presented in more detail in Appendix I. 1. Cayo Santiago, 2. Cayo Batata, 3. Cayo de Afuera, 4. Cayo de Tierra, 5. Cardona Key, 6. Protestant Key, 7. Green Key (st. ~roix), 8. Caiia Azul ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN 251 ERRATUM The following caption should be inserted for figure 7: Fig. 7. Temperature in and near a small clump of vegetation on Cayo Ahogado. Dots: 5 cm deep in soil under clump. Circles: 1 cm deep in soil under clump. Triangles: Soil surface under clump. Squares: Surface of vegetation. X's: Air at center of clump. Broken line indicates intervals of more than one hour between measurements. BIOGEOGRAPHY OF THE PUERTO RICAN BANK by Harold Heatwolel, Richard Levins2 and Michael D. Byer3 INTRODUCTION There has been a recent surge of interest in the biogeography of archipelagoes owing to a reinterpretation of classical concepts of evolution of insular populations, factors controlling numbers of species on islands, and the dynamics of inter-island dispersal. The literature on these subjects is rapidly accumulating; general reviews are presented by Mayr (1963) , and Baker and Stebbins (1965) . Carlquist (1965, 1974), Preston (1962 a, b), ~ac~rthurand Wilson (1963, 1967) , MacArthur et al. (1973) , Hamilton and Rubinoff (1963, 1967), Hamilton et al. (1963) , Crowell (19641, Johnson (1975) , Whitehead and Jones (1969), Simberloff (1969, 19701, Simberloff and Wilson (1969), Wilson and Taylor (19671, Carson (1970), Heatwole and Levins (1973) , Abbott (1974) , Johnson and Raven (1973) and Lynch and Johnson (1974), have provided major impetuses through theoretical and/ or general papers on numbers of species on islands and the dynamics of insular biogeography and evolution. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Yachtcharter - Yachtcharter Tortola

VPM Yachtcharter - Yachtcharter Tortola Yacht - charter Yachtcharter Tortola Tortola has been a cradle of yachting for half a century now. The archipelago of the Virgin Islands seems to be created to fulfill all the wishes of those who cannot get enough of smooth sailing trips. Protected by a chain of small islands with innumerable beaches, the waters are always calm here, the trade winds blow steadily and the places to drop anchor are calm. The numerous restaurants and bars offer the sailors a comfort that is unique in the Caribbean. The beauty of the landscape, the security of the waters and the hospitality of the inhabitants make the Virgin Islands to a favorite sailing destination for yachtcharter. On a Yachtcharter starting in Tortola you will find small distances that will allow you to perform navigation on sight. The Caribbean is the ideal place for newcomers, families and those who like to enjoy. For a trip to the Virgins, which are located on US territory, you need a visa. Our VPM - Yachtcharter base in Tortola is located in Nanny Cay near Road Town. view map in fullscreen Sailing Weather Tortola: Since the islands are located in the Passat belt, the wind blows steadily from November to May from NO. In autumn and summer, however, he turns to O to SO. A constant wind sailing is therefore to be expected. In winter it can be cold fronts with stormy winds from N to NW. The hurricane season is from August to October. Best Sailing time Tortola: November to mid-April Airports near your sailing area Tortola: Tortola (EIS) - Nanny Cay: about 20 km Necessary licenses for your cruise Tortola: A special license is not required, but a sailing experience detection. -

Waste Management Strategy for the British Virgin Islands Ministry of Health & Social Development

FINAL REPORT ON WASTE MANAGEMENT WASTE CHARACTERISATION STRATEGY FOR THE BRITISH J U L Y 2 0 1 9 VIRGIN ISLANDS Ref. 32-BV-2018Waste Management Strategy for the British Virgin Islands Ministry of Health & Social Development TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS..............................................................................2 1 INTRODUCTION.........................................................3 1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY..........................................................3 1.2 SUBJECT OF THE PRESENT REPORT..................................................3 1.3 OBJECTIVE OF THE WASTE CHARACTERISATION................................3 2 METHODOLOGY.........................................................4 2.1 ORGANISATION AND IMPLEMENTATION OF THE WASTE CHARACTERISATION....................................................................4 2.2 LIMITATIONS AND DIFFICULTIES......................................................6 3 RESULTS...................................................................7 3.1 GRANULOMETRY.............................................................................7 3.2 GRANULOMETRY.............................................................................8 3.2.1 Overall waste composition..................................................................8 3.2.2 Development of waste composition over the years..........................11 3.2.3 Waste composition per fraction........................................................12 3.3 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.................................................................17 -

British Virgin Islands

THE NATIONAL REPORT EL REPORTE NACIONAL FOR THE COUNTRY OF POR EL PAIS DE BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVE / REPRESENTANTE NACIONAL LOUIS WALTERS Western Atlantic Turtle Symposium Simposio de Tortugas del Atlantico Occidental 17-22 July / Julio 1983 San José, Costa Rica BVI National Report, WATS I Vol 3, pages 70-117 WESTERN ATLANTIC TURTLE SYMPOSIUM San José, Costa Rica, July 1983 NATIONAL REPORT FOR THE COUNTRY OF BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS NATIONAL REPORT PRESENTED BY Louis Walters The National Representative Address: Permanent Secretary, Ministry of National Resources and Environment Tortola, British Virgin Islands NATIONAL REPORT PREPARED BY John Fletemeyer DATE SUBMITTED: 2 June 1983 Please submit this NATIONAL REPORT no later than 1 December 1982 to: IOC Assistant Secretary for IOCARIBE ℅ UNDP, Apartado 4540 San José, Costa Rica BVI National Report, WATS I Vol 3, pages 70-117 With a grant from the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service, WIDECAST has digitized the data- bases and proceedings of the Western Atlantic Turtle Symposium (WATS) with the hope that the revitalized documents might provide a useful historical context for contemporary sea turtle management and conservation efforts in the Western Atlantic Region. With the stated objective of serving “as a starting point for the identification of critical areas where it will be necessary to concentrate all efforts in the future”, the first Western Atlantic Turtle Sym- posium convened in Costa Rica (17-22 July 1983), and the second in Puerto Rico four years later (12-16 October 1987). WATS I featured National Reports from 43 political jurisdictions; 37 pre- sented at WATS II. -

Yachting - Yachtcharter Tortola

Barone Yachting - Yachtcharter Tortola Yacht - charter Yachtcharter Tortola Tortola has been a cradle of yachting for half a century now. The archipelago of the Virgin Islands seems to be created to fulfill all the wishes of those who cannot get enough of smooth sailing trips. Protected by a chain of small islands with innumerable beaches, the waters are always calm here, the trade winds blow steadily and the places to drop anchor are calm. The numerous restaurants and bars offer the sailors a comfort that is unique in the Caribbean. The beauty of the landscape, the security of the waters and the hospitality of the inhabitants make the Virgin Islands to a favorite sailing destination for yachtcharter. On a Yachtcharter starting in Tortola you will find small distances that will allow you to perform navigation on sight. The Caribbean is the ideal place for newcomers, families and those who like to enjoy. For a trip to the Virgins, which are located on US territory, you need a visa. Our VPM - Yachtcharter base in Tortola is located in Nanny Cay near Road Town. view map in fullscreen Sailing Weather Tortola: Since the islands are located in the Passat belt, the wind blows steadily from November to May from NO. In autumn and summer, however, he turns to O to SO. A constant wind sailing is therefore to be expected. In winter it can be cold fronts with stormy winds from N to NW. The hurricane season is from August to October. Best Sailing time Tortola: November to mid-April Airports near your sailing area Tortola: Tortola (EIS) - Nanny Cay: about 20 km Necessary licenses for your cruise Tortola: A special license is not required, but a sailing experience detection. -

Jost Van Dyke, British Virgin Islands

An Environmental Profile of the Island of Jost Van Dyke, British Virgin Islands including Little Jost Van Dyke, Sandy Cay, Green Cay and Sandy Spit This publication was made possible with funding support from: UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office Department for International Development Overseas Territories Environment Programme An Environmental Profile of the Island of Jost Van Dyke, British Virgin Islands including Little Jost Van Dyke, Sandy Cay, Green Cay and Sandy Spit An Initiative of the Jost Van Dykes (BVI) Preservation Society and Island Resources Foundation 2009 This publication was made possible by Use of Profile: Available from: the generous support of the Overseas Reproduction of this publication, or Jost Van Dykes (BVI) Preservation Territories Environment Programme portions of this publication, is Society (OTEP), UK Foreign and authorized for educational or non- Great Harbour Commonwealth Office, under a commercial purposes without prior Jost Van Dykes, VG 1160 contract between OTEP and the Jost permission of the Jost Van Dykes (BVI) British Virgin Islands Van Dykes (BVI) Preservation Society Preservation Society or Island Tel 284.540.0861 (JVDPS), for implementation of a Resources Foundation, provided the www.jvdps.org project identified as: source is fully acknowledged. www.jvdgreen.org BVI503: Jost Van Dyke’s Community- based Programme Advancing Citation: Island Resources Foundation Environmental Protection and Island Resources Foundation and Jost 1718 P Street Northwest, Suite T-4 Sustainable Development. Van Dykes (BVI) Preservation Society Washington, DC 20036 USA (2009). An Environmental Profile of the Tel 202.265.9712 The JVDPS contracted with Island Island of Jost Van Dyke, British Virgin Fax 202.232.0748 Resources Foundation to provide Islands, including Little Jost Van Dyke, www.irf.org technical services as a part of its Sandy Cay, Green Cay and Sandy agreement with OTEP, in particular to Spit. -

Annual Report

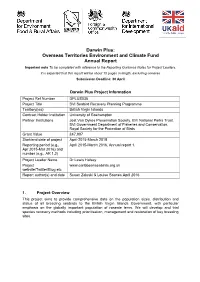

Darwin Plus: Overseas Territories Environment and Climate Fund Annual Report Important note To be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be about 10 pages in length, excluding annexes Submission Deadline: 30 April Darwin Plus Project Information Project Ref Number DPLUS035 Project Title BVI Seabird Recovery Planning Programme Territory(ies) British Virgin Islands Contract Holder Institution University of Roehampton Partner Institutions Jost Van Dykes Preservation Society, BVI National Parks Trust, BVI Government Department of Fisheries and Conservation, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds Grant Value £47,907 Start/end date of project April-2015-March 2018 Reporting period (e.g., April 2015-March 2016, Annual report 1. Apr 2015-Mar 2016) and number (e.g., AR 1,2) Project Leader Name Dr Lewis Halsey Project www.caribbeanseabirds.org.uk website/Twitter/Blog etc Report author(s) and date Susan Zaluski & Louise Soanes April 2016 1. Project Overview This project aims to provide comprehensive data on the population sizes, distribution and status of all breeding seabirds to the British Virgin Islands Government, with particular emphasis on the globally important population of roseate terns. We will develop and trial species recovery methods including prioritisation, management and restoration of key breeding sites. 2. Project Progress 2.1 Progress in carrying out project activities Please see table below detailing project activities and progress made towards achieving them Activities to be Progress in meeting project activities undertaken Output 1 Comprehensive 1.1 All cays During June 2015 27 out of 50 cays were circumnavigated by Seabird surveyed for boat and 11 of the more accessible, larger islands were Surveys of the summer breeding surveyed by foot.