Scottish War of 1558 and the Scottish Reformation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

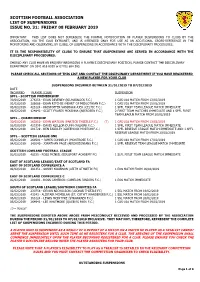

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

The Macgill--Mcgill Family of Maryland

SEP i ma The MaCgÍll - McGill Family of Maryland A Genealogical Record of over 400 years Beginning 1537, ending 1948 GENEALOGICAL SOCIETÏ OP THE CHURCH OF JlSUS CMOlSI OP UT7Sfc.DAY SAMS DATE MICROFILMED ITEM PROJECT and G. S. Compiled ROLL # CALL # by John McGill 1523 22nd St., N. W Washington, D. C. Copyright 1948 by John McGill Macgill Coat-of-Arms Arms, Gules, three martlets, argent. Crest, a phoenix in flames, proper. Supporters, dexter (right) a horse at liberty, argent, gorged with a collar with a chain thereto affixed, maned and hoofed or, sinister (left) a bull sable, collared and chained as the former. Motto: Sine Fine (meaning without end). Meaning of colors and symbols Gules (red) signifies Military Fortitude and Magnanimity. Argent (silver) signifies Peace and Sincerety. Or (gold) signifies Generosity and Elevation of Mind. Sable (black) signifies Constancy. Proper (proper color of object mentioned). The martlet or swallow is a favorite device in European heraldry, and has assumed a somewhat unreal character from the circumstance that it catches its food on the wing and never appears to light on the ground as other birds do. It is depicted in armory always with wings close and in pro file, with no visable legs or feet. The martlet is the appropriate "differ ence" or mark of cadency for the fourth son. It is modernly used to signify, as the bird seldom lights on land, so younger brothers have little land to rest on but the wings of their own endeavor, who, like the swallows, become the travellers in their season. -

107394589.23.Pdf

Scs s-r<?s/ &.c £be Scottish tlert Society SATIRICAL POEMS OF THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION SATIRICAL POEMS OF THE TIME OF THE REFORMATION EDITED BY JAMES CRANSTOUN, LL.D. VOL. II. ('library''. ) Printcti fat tljt Sacietg Iig WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON MDCCCXCIII V PREFATORY NOTE TO VOL. II. The present volume is for the most part occupied with Notes and Glossary. Two poems by Thomas Churchyard — “ The Siege of Edenbrough Castell ” and “ Mvrtons Tragedie ”—have been included, as possessing considerable interest of themselves, and as illustrating two important poems in the collection. A complete Index of Proper Names has also been given. By some people, I am aware, the Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation that have come down to us through black- letter broadsheets are considered as of little consequence, and at best only “sorry satire.” But researches in the collections of historical manuscripts preserved in the State-Paper Office and the British Museum have shown that, however deficient these ballads may be in the element of poetry, they are eminently trustworthy, and thus have an unmistakable value, as contemporary records. A good deal of pains has accordingly been taken, by reference to accredited authorities, to explain unfamiliar allusions and clear up obscure points in the poems. It is therefore hoped that not many difficulties remain to perplex the reader. A few, however, have defied solution. To these, as they occurred, I have called attention in the notes, with a view to their being taken up by others who, with greater knowledge of the subject or ampler facilities for research than I possess, may be able to elucidate them. -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

The Admission of Ministers in the Church of Scotland

THE ADMISSION OF MINISTERS IN THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND 1560-1652. A Study la Fresfcgrteriaa Ordination. DUNCAN SHAW. A Thesis presented to THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW, For the degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY, after study la THE DEPARTMENT OF ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY, April, 1976. ProQuest Number: 13804081 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13804081 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 X. A C KNQWLEDSMENT. ACKNOWLEDGMENT IS MADE OF TIE HELP AND ADVICE GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS BY THE REV. IAN MUIRHEAD, M.A., B.D., SENIOR LECTURER IN ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW. II. TABLES OP CONTENTS PREFACE Paso 1 INTRODUCTION 3 -11 The need for Reformation 3 Clerical ignorance and corruption 3-4 Attempto at correction 4-5 The impact of Reformation doctrine and ideas 5-6 Formation of the "Congregation of Christ" and early moves towards reform 6 Desire to have the Word of God "truelie preached" and the Sacraments "rightlie ministred" 7 The Reformation in Scotland -

Lviemoirs of JOHN KNOX

GENEALOGICAL lVIEMOIRS OF JOHN KNOX AXIJ OF THE FAMILY OF KNOX BY THE REV. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D. fF'.LLOW OF THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAXD, FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF XORTHER-N A:NTIQ:;ARIES, COPENHAGEN; FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF NEW SOCTH WALES, ASSOCIATE OF THE IMPRRIAL ARCIIAWLOGICAL SOCIETY OF Rl'SSIA, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF QL'EBEC, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA, A!'i'D CORRESPOXDING MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ENGLA:ND PREF ACE. ALL who love liberty and value Protestantism venerate the character of John Knox; no British Reformer is more entitled to the designation of illustrious. By three centuries he anticipated that parochial system of education which has lately become the law of England; by nearly half that period he set forth those principles of civil and religious liberty which culminated in a system of constitutional government. To him Englishmen are indebted for the Protestant character of their "Book of Common Prayer;" Scotsmen for a Reforma tion so thorough as permanently to resist the encroachments of an ever aggressive sacerdotalism. Knox belonged to a House ancient and respectable; but those bearing his name derive their chiefest lustre from 1eing connected with a race of which he was a member. The family annals presented in these pages reveal not a few of the members exhibiting vast intellectual capacity and moral worth. \Vhat follows is the result of wide research and a very extensive correspondence. So many have helped that a catalogue of them ,...-ould be cumbrous. -

127639442.23.Pdf

•KlCi-fr-CT0! , Xit- S»cs fS) hcyi'* SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FOURTH SERIES VOLUME 4 The Court Books of Orkney and Shetland The Earl's Palace, Kirkwall, Orkney Scalloway Castle, Shetland THE COURT BOOKS OF Orkney and Shedand 1614-1615 transcribed and edited by Robert S. Barclay B.SC., PH.D., F.R.S.E. EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by T. AND A. CONSTABLE LTD I967 Scottish History Society 1967 ^iG^Feg ^ :968^ Printed in Great Britain PREFACE My warmest thanks are due to Mr John Imrie, Curator of Historical Records, H.M. General Register House, and to Professor Gordon Donaldson of the Department of Scottish History, Edinburgh University, for their scholarly advice so freely given, and for their unfailing courtesy. R.S.B. Edinburgh June, 1967 : A generous contribution from the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland towards the cost of producing this volume is gratefully acknowledged by the Council of the Society CONTENTS Preface page v INTRODUCTION page xi The Northern Court Books — The Court Books described Editing the transcript - The historical setting The scope of the Court Books THE COURT BOOK OF THE BISHOPRIC OF ORKNEY 1614- 1615 page 1 THE COURT BOOK OF ORKNEY 1615 page 11 THE COURT BOOK OF SHETLAND 1615 page 57 Glossary page 123 Index page 129 03 ILLUSTRATIONS The Earl’s Palace, Kirkwall, Orkney Scalloway Castle, Shetland Crown copyright photographs reproduced by permission of Ministry of PubUc Building and Works frontispiece Facsimile from Court Book of Orkney, folio 49V. page 121 m INTRODUCTION THE NORTHERN COURT BOOKS This is the third volume printed in recent years of proceedings in the sheriff courts of Orkney and Shetland in the early decades of the seventeenth century. -

Red Book of Scotland Vol 10

THE RED BOOK OF SCOTLAND THE RED BOOK OF SCOTLAND THE RED BOOK OF SCOTLAND SUPPLEMENT & BIBLIOGRAPHY Gordon MacGregor www.redbookofscotland.co.uk Copyright © Gordon MacGregor 2018 The moral right of the author has been asserted First Published 2016 This Edition Published 2019 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. PRODUCED IN SCOTLAND ISBN 978-0-9545628-6-1 Red Book of Scotland |1 C o n t e n t s _______ Foreword . 3 Acknowledgements . 4 Bibliography . 7 2 | Red Book of Scotland Red Book of Scotland |3 FOREWORD The Red Book of Scotland is an outstanding historical and genealogical resource, recording the genealogy of many of Scotland’s families that are of importance both nationally and locally. It is an immensely useful resource for historians in Scotland trying to place significant individuals in their historical context when acting in national and local affairs. Gordon MacGregor has put in many years research into the production of this nine volume magnus opum collection of genealogies with the entry for each person clearly referenced. I have worked with Gordon MacGregor on a number of successful claims to titles and clan chiefships in the Court of the Lord Lyon, where his evidence has been accepted by the Lord Lyon, King of Arms who accepted “that Mr MacGregor has experience as a genealogical record researcher and has knowledge of researching in Scottish records”. -

Alisona De Saluzzo

Alisona de Saluzzo 1-Alisona de Saluzzo b. Abt 1267, Arundel,Essex,England, d. 25 Sep 1292 +Richard FitzAlan, 7th Earl b. 3 Feb 1267, of Arundel,Essex,England, d. 9 Mar 1302 2-Eleanor FitzAlan, [Baroness Percy] b. Abt 1283, of,Arundel,Sussex,England, d. Jul 1328 +Henry de Percy, [Baron Percy] b. 25 Mar 1272, ,Alnwick,Northumberland,England, d. Oct 1314, ,Fountains Abbey,Yorkshire,England 3-Henry de Percy, 11th Baron Percy b. 6 Feb 1301, ,Leconfield,Yorkshire,England, d. 25 Feb 1352, ,Warkworth,Northumberland,England +Idonea de Clifford b. 1300, of Appleby Castle,Westmorland,England, d. 24 Aug 1365 4-Henry de Percy, Baron Percy b. 1320, of Castle,Alnwick,Northumberland,England, d. 18 May 1368 +Mary Plantagenet b. 1320, d. 1362 5-Sir Henry de Percy, 4th Lord b. 10 Nov 1341, of,Alnwick,Northumberland,England, d. Abt 19 Feb 1407 +Margaret Neville, Baroness Ros b. Abt 1329, of,Raby,Durham,England, d. 12 May 1372 6-Isolda Percy b. Abt 1362, of Warkworth Castle. Northumberland,England, d. 1403, Battle of Shrewsbury +Madog Kynaston b. Abt 1350, of Stocks,Shropshire,England, d. 1403, Battle of Shrewsbury 7-John Kynaston b. Abt 1375, of Stocks,Shropshire,England +Unknown 8-Griffith Kynaston b. Abt 1396, of Stocks,Shropshire,England +Margaret (Jane) Hoorde 9-John or Jenkyn Kynaston, Esq. +Jane Manwaring 10-Pierce Kynaston +Margaret vz Edward 11-Humfry Kynaston +Elizabeth Oatley 12-George Kynaston d. 8 Dec 1543 9-Philip Kynaston b. Abt 1417, Of Walford +Alice Dorothy Corbet b. Abt 1411, ,Moreton Corbet,Shropshire,England, d. Abt 1443 9-William Kynaston 9-Sir Roger Kynaston b. -

Henrydundasvisco00lovauoft.Pdf

HENRY DUNDAS VISCOUNT MELVILLE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, MANAGER ILonBon: FETTER LANE, E.G. I0 PRINCES STREET fo Sorft: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS AND LTD. , Calcutta anB flSatoraa: MACMILLAN CO., aTotonto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, LTD. THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA All rights reserved Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville HENRY DUNDAS VISCOUNT MELVILLE BY J. A. LOVAT-FRASER, M.A. Author of John Stuart, Earl of Bute Cambridge : at the University Press 1916 TO ARTHUR STEEL-MAITLAND, M.P. UNDER-SECRETARY FOR THE COLONIES CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER I i CHAPTER II 12 CHAPTER III 23 CHAPTER IV 3 1 CHAPTER V 42 CHAPTER VI 54 CHAPTER VII 66 CHAPTER VIII 76 CHAPTER IX 82 CHAPTER X .92 CHAPTER XI 103 CHAPTER XII 115 CHAPTER XIII 127 LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL AUTHORITIES USED BY THE AUTHOR . 142 INDEX 144 PORTRAIT OF HENRYDUNDAS, VISCOUNT MELVILLE .... Frontispiece INTRODUCTION St Andrew Square, Edinburgh, the passer-by may INsee standing on a lofty pillar the statue of Henry Dundas, first Viscount Melville, the colleague and friend of the younger Pitt. The towering height of the monu- ment is itself emblematic of the lofty position held by Dundas in his native country at the end of the eighteenth century. For many years he exercised in Scotland a sway so absolute that he was nicknamed "Harry the Ninth." The heaven-soaring statue proclaims to the world how great was his position in the eyes of his contemporaries. Beginning as Lord Advocate, he filled in a succession of British Governments the most important offices, and played an outstanding part in the history of his time. -

The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair', Edinburgh Law Review, Vol

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2007, 'The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair', Edinburgh Law Review, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 300-48. https://doi.org/10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Edinburgh Law Review Publisher Rights Statement: ©Cairns, J. (2007). The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair. Edinburgh Law Review, 11, 300-48doi: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 EdinLR Vol 11 pp 300-348 The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair John W Cairns* A. INTRODUCTION B. EARLIER VIEWS ON THE FOUNDING OF THE CHAIR C.