Copyright Undertaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Address Telephone G/F, 500 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2833

Address Telephone G/F, 500 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2833 1918 Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Sentact Building, 345 King's Road, North Point, HK 2566 3262 Shop 1, G/F, Regent Centre, 88 Queen’s Road Central, HK 2521 2928 G/F & 1/F, 6 D'Aguilar Street, Central, HK 2530 3933 G/F & 1/F, 72&74 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, HK 2895 6112 Shop F35 - F38, 1/F, Kornhill Plaza, 1-2 Kornhill Road, Quarry Bay, HK 2513 1733 Shop G08 & G10, G/F, Port Centre, 38 Chengtu Road, Aberdeen, HK 2580 8811 Shop 312-315, 3/F, New Jade Shopping Arcade, 233 Chai Wan Road, Chai Wan, HK 2976 5620 Shop 3A & B, G/F & 1/F, AT Tower, 180 Electric Road, Fortress Hill, HK 2578 1002 Shop 32-34, 1/F, The Peak Galleria, 118 Peak Road, HK 2849 2868 G/F & 1/F, 108 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, HK 2146 1333 Shop G19 & B01, G/F & B/F, Causeway Bay Plaza 1, 489 Hennessy Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2503 3887 G/F, 541 & 543 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2253 6092 G/F & 2/F, Leighton Centre, 77 Leighton Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2555 0806 G/F & 1/F, 50 Yun Ping Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2501 0281 Shop 118-119, 1/F, Windsor House, 311 Gloucester Road, Causeway Bay, HK 2177 3368 G/F & 1/F, 8 Russell Street, Causeway Bay, H.K. 2702 0533 G/F, 88 Wing Lok Street, Sheung Wan, HK 2253 0071 G/F, 60-62 Yee Wo Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2697 9322 Shop 234-235, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 168-200 Connaught Road Central, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong 2559 1288 Shop 205, Podium Level 2, The Westwood, No. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL on TRANSPORT Pedestrian Schemes for Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui Introduction This Paper

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL PANEL ON TRANSPORT Pedestrian Schemes for Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui Introduction This paper informs members of the details of the proposed pedestrian schemes for Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui. Background 2. At the meeting of the LegCo Panel on Transport held on 25 February 2000, the Administration presented the objectives and the general concept adopted in devising pedestrian schemes with particular reference to the Causeway Bay scheme as illustration. Members requested the Administration to provide details of the Mong Kok and Tsim Sha Tsui pedestrian schemes for information. Pedestrian Scheme for Mong Kok 3. The pedestrian scheme in Mong Kok covers the area bounded by Argyle Street, Nathan Road, Dundas Street and Fa Yuen Street as shown in Figures 1 and 1A. 4. The substantial commercial, retail and other economic activities in Mong Kok generate significant transport needs, e.g. loading and unloading, access by public transport, and access to car parks. To ensure general access to this area will be maintained, the pedestrian scheme targets the streets where pedestrian activities are most concentrated. Sections of Nelson Street and Soy Street between Nathan Road and Sai Yeung Choi Street South are designated as fully pedestrianised streets. In addition, Tung Choi Street and the section of Sai Yeung Choi Street South between Nelson Street and Soy Street would be designated as part-time pedestrianised streets. Vehicles, other than emergency vehicles, would not be permitted to enter the streets during specified hours, initially between 4 pm to mid-night. 5. The rest of the streets within the area would be designated as mixed priority streets. -

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total No

List of Electors with Authorised Representatives Appointed for the Labour Advisory Board Election of Employee Representatives 2020 (Total no. of electors: 869) Trade Union Union Name (English) Postal Address (English) Registration No. 7 Hong Kong & Kowloon Carpenters General Union 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. 8 Hong Kong & Kowloon European-Style Tailors Union 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 15 Hong Kong and Kowloon Western-styled Lady Dress Makers Guild 6/F, Sunbeam Commerical Building,469-471 Nathan Road, Yaumatei, Kowloon. 17 HK Electric Investments Limited Employees Union 6/F., Kingsfield Centre, 18 Shell Street,North Point, Hong Kong. Hong Kong & Kowloon Spinning, Weaving & Dyeing Trade 18 1/F., Kam Fung Court, 18 Tai UK Street,Tsuen Wan, N.T. Workers General Union 21 Hong Kong Rubber and Plastic Industry Employees Union 1st Floor, 20-24 Choi Hung Road,San Po Kong, Kowloon DAIRY PRODUCTS, BEVERAGE AND FOOD INDUSTRIES 22 368-374 Lockhart Road, 1/F.,Wan Chai, Hong Kong. EMPLOYEES UNION Hong Kong and Kowloon Bamboo Scaffolding Workers Union 28 2/F, Wah Hing Com. Centre,383 Shanghai St., Yaumatei, Kln. (Tung-King) Hong Kong & Kowloon Dockyards and Wharves Carpenters 29 2/F, Wah Hing Commercial Centre,383 Shanghai Street, Yaumatei, Kln. General Union 31 Hong Kong & Kowloon Painters, Sofa & Furniture Workers Union 1/F, 368 Lockhart Road,Pakling Building,Wanchai, Hong Kong. 32 Hong Kong Postal Workers Union 2/F., Cheng Hong Building,47-57 Temple Street, Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon. 33 Hong Kong and Kowloon Tobacco Trade Workers General Union 1/F, Pak Ling Building,368-374 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, Hong Kong HONG KONG MEDICAL & HEALTH CHINESE STAFF 40 12/F, United Chinese Bank Building,18 Tai Po Road,Sham Shui Po, Kowloon. -

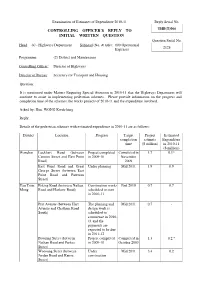

THB(T)066 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY to INITIAL WRITTEN QUESTION Question Serial No

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2010-11 Reply Serial No. THB(T)066 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY TO INITIAL WRITTEN QUESTION Question Serial No. Head: 60 - Highways Department Subhead (No. & title): 000 Operational 2128 Expenses Programme: (2) District and Maintenance Controlling Officer: Director of Highways Director of Bureau: Secretary for Transport and Housing Question: It is mentioned under Matters Requiring Special Attention in 2010-11 that the Highways Department will continue to assist in implementing pedestrian schemes. Please provide information on the progress and completion time of the schemes, the works projects of 2010-11 and the expenditure involved. Asked by: Hon. WONG Kwok-hing Reply: Details of the pedestrian schemes with estimated expenditure in 2010-11 are as follows: District Location Progress Target Project Estimated completion estimate Expenditure time ($ million) in 2010-11 ($ million) Wanchai Lockhart Road (between Project completed Completed in 1.7 0.1* Cannon Street and East Point in 2009-10 November Road) 2009 East Point Road and Great Under planning Mid 2011 1.9 0.9 George Street (between East Point Road and Paterson Street) Yau Tsim Peking Road (between Nathan Construction works End 2010 0.7 0.7 Mong Road and Hankow Road) scheduled to start in 2010-11 Prat Avenue (between Hart The planning and Mid 2011 0.7 - Avenue and Chatham Road design work is South) scheduled to commence in 2010 11 and the payments are expected to be due in 2011-12 Bowring Street (between Project completed Completed in 1.3 0.2 -

When Is the Best Time to Go to Hong Kong?

Page 1 of 98 Chris’ Copyrights @ 2011 When Is The Best Time To Go To Hong Kong? Winter Season (December - March) is the most relaxing and comfortable time to go to Hong Kong but besides the weather, there's little else to do since the "Sale Season" occurs during Summer. There are some sales during Christmas & Chinese New Year but 90% of the clothes are for winter. Hong Kong can get very foggy during winter, as such, visit to the Peak is a hit-or-miss affair. A foggy bird's eye view of HK isn't really nice. Summer Season (May - October) is similar to Manila's weather, very hot but moving around in Hong Kong can get extra uncomfortable because of the high humidity which gives the "sticky" feeling. Hong Kong's rainy season also falls on their summer, July & August has the highest rainfall count and the typhoons also arrive in these months. The Sale / Shopping Festival is from the start of July to the start of September. If the sky is clear, the view from the Peak is great. Avoid going to Hong Kong when there are large-scale exhibitions or ongoing tournaments like the Hong Kong Sevens Rugby Tournament because hotel prices will be significantly higher. CUSTOMS & DUTY FREE ALLOWANCES & RESTRICTIONS • Currency - No restrictions • Tobacco - 19 cigarettes or 1 cigar or 25 grams of other manufactured tobacco • Liquor - 1 bottle of wine or spirits • Perfume - 60ml of perfume & 250 ml of eau de toilette • Cameras - No restrictions • Film - Reasonable for personal use • Gifts - Reasonable amount • Agricultural Items - Refer to consulate Note: • If arriving from Macau, duty-free imports for Macau residents are limited to half the above cigarette, cigar & tobacco allowance • Aircraft crew & passengers in direct transit via Hong Kong are limited to 20 cigarettes or 57 grams of pipe tobacco. -

Restaurant List

Restaurant List (updated 1 July 2020) Island Cafeholic Shop No.23, Ground Floor, Fu Tung Plaza, Fu Tung Estate, 6 Fu Tung Street, Tung Chung First Korean Restaurant Shop 102B, 1/F, Block A, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, Lantau Island Grand Kitchen Shop G10-101, G/F, JoysMark Shopping Centre, Mung Tung Estate, Tung Chung Gyu-Kaku Jinan-Bou Shop 706, 7th Floor, Citygate Outlets, Tung Chung HANNOSUKE (Tung Chung Citygate Outlets) Shop 101A, 1st Floor, Citygate, 18-20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Hung Fook Tong Shop No. 32, Ground Floor, Yat Tung Shopping Centre, Yat Tung Estate, 8 Yat Tung Street, Tung Chung Island Café Shop 105A, 1/F, Block A, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, Lantau Island Itamomo Shop No.2, G/F, Ying Tung Shopping Centre, Ying Tung Estate, 1 Ying Tung Road, Lantau Island, Tung Chung KYO WATAMI (Tung Chung Citygate Outlets) Shop B13, B1/F, Citygate Outlets, 20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island Moon Lok Chiu Chow Unit G22, G/F, Citygate, 20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island Mun Tung Café Shop 11, G/F, JoysMark Shopping Centre, Mun Tung Estate, Tung Chung Paradise Dynasty Shop 326A, 3/F, Citygate, 18-20 Tat Tung Road, Tung Chung, Lantau Island Shanghai Breeze Shop 104A, 1/F, Block A, D’Deck, Discovery Bay, Lantau Island The Sixties Restaurant No. 34, Ground Floor, Commercial Centre 2, Yat Tung Estate, 8 Yat Tung Street, Tung Chung 十足風味 Shop N, G/F, Seaview Crescent, Tung Chung Waterfront Road, Tung Chung Kowloon City Yu Mai SHOP 6B G/F, Amazing World, 121 Baker Street, Site 1, Whampoa Garden, Hung Hom CAFÉ ABERDEEN Shop Nos. -

Designated 7-11 Convenience Stores

Store # Area Region in Eng Address in Eng 0001 HK Happy Valley G/F., Winner House,15 Wong Nei Chung Road, Happy Valley, HK 0009 HK Quarry Bay Shop 12-13, G/F., Blk C, Model Housing Est., 774 King's Road, HK 0028 KLN Mongkok G/F., Comfort Court, 19 Playing Field Rd., Kln 0036 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, TAL Building, 45-53 Austin Road, Kln 0077 KLN Kowloon City Shop A-D, G/F., Leung Ling House, 96 Nga Tsin Wai Rd, Kowloon City, Kln 0084 HK Wan Chai G6, G/F, Harbour Centre, 25 Harbour Rd., Wanchai, HK 0085 HK Sheung Wan G/F., Blk B, Hiller Comm Bldg., 89-91 Wing Lok St., HK 0094 HK Causeway Bay Shop 3, G/F, Professional Bldg., 19-23 Tung Lo Wan Road, HK 0102 KLN Jordan G/F, 11 Nanking Street, Kln 0119 KLN Jordan G/F, 48-50 Bowring Street, Kln 0132 KLN Mongkok Shop 16, G/F., 60-104 Soy Street, Concord Bldg., Kln 0150 HK Sheung Wan G01 Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Rd C, HK-Macau Ferry Terminal, HK 0151 HK Wan Chai Shop 2, 20 Luard Road, Wanchai, HK 0153 HK Sheung Wan G/F., 88 High Street, HK 0226 KLN Jordan Shop A, G/F, Cheung King Mansion, 144 Austin Road, Kln 0253 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui East Shop 1, Lower G/F, Hilton Tower, 96 Granville Road, Tsimshatsui East, Kln 0273 HK Central G/F, 89 Caine Road, HK 0281 HK Wan Chai Shop A, G/F, 151 Lockhart Road, Wanchai, HK 0308 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 1 & 2, G/F, Hart Avenue Plaza, 5-9A Hart Avenue, TST, Kln 0323 HK Wan Chai Portion of shop A, B & C, G/F Sun Tao Bldg, 12-18 Morrison Hill Rd, HK 0325 HK Causeway Bay Shop C, G/F Pak Shing Bldg, 168-174 Tung Lo Wan Rd, Causeway Bay, HK 0327 KLN Tsim Sha Tsui Shop 7, G/F Star House, 3 Salisbury Road, TST, Kln 0328 HK Wan Chai Shop C, G/F, Siu Fung Building, 9-17 Tin Lok Lane, Wanchai, HK 0339 KLN Kowloon Bay G/F, Shop No.205-207, Phase II Amoy Plaza, 77 Ngau Tau Kok Road, Kln 0351 KLN Kwun Tong Shop 22, 23 & 23A, G/F, Laguna Plaza, Cha Kwo Ling Rd., Kwun Tong, Kln. -

Recreation, Sport and the Arts

Chapter 19 Recreation, Sport, Culture and the Arts Hong Kong’s hard-working people enjoy a wide variety of sports, cultural and recreational opportunities, whether as participants or spectators. They range from major international sports and arts events to community programmes in which people of all ages and abilities can take part. The Home Affairs Bureau (HAB) co-ordinates government policies on recreation, sports, culture and heritage. Organisations such as the Sports Commission and the Hong Kong Arts Development Council help the government in drawing up these policies. The Sports Commission advises on all matters relating to sports development and oversees committees on community sports, elite sports and major sports events. The Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD), an executive arm of HAB, provides services to preserve Hong Kong’s cultural heritage, enhance its physical environment, and foster co-operative interaction between sports, cultural and community organisations. The LCSD organises exhibitions, sporting events and cultural performances ranging from music and dance to opera. Recreation and Sports The LCSD develops and co-ordinates the provision of high quality recreational and sports facilities for leisure enjoyment including parks, landscaped open spaces, sports grounds, playgrounds, sports centres, holiday camps, water sports centres, swimming pools and beaches. It also organises and supports a wide variety of recreation and sports programmes to promote community sports, identify sporting talent and raise sporting standards. It works closely with the District Councils (DCs), the National Sports Associations under the auspices of the Sports Federation and Olympic Committee of Hong Kong, China, District Sports Associations, and schools to promote sport-for-all and encourage everyone to participate in sports and recreational activities. -

Download PDF File Format Form

Quality Services for Quality Life Annual Report 2018-2019 Contents Pages 1. Foreword 1-4 2. Performance Pledges 5-6 3. Vision, Mission & Values 7-8 4. Leisure Services 9-56 Leisure Services 9 Recreational and Sports Facilities 10-28 Recreational and Sports Programmes 29-35 Sports Subvention Scheme 36-38 2018 Asian Games and Asian Para Games in Indonesia 39-40 The 7th Hong Kong Games 41-42 Sports Exchange and Co-operation Programmes 43 Horticulture and Amenities 44-46 Green Promotion 47-52 Licensing 53 Major Recreational and Sports Events 54-56 5. Cultural Services 57-165 Cultural Services 57 Performing Arts 58-62 Cultural Presentations 63-69 Contents Pages Festivals 70-73 Arts Education and Audience-Building Programmes 74-80 Carnivals and Entertainment Programmes 81-84 Cultural Exchanges 85-91 Film Archive and Film and Media Arts Programmes 92-97 Music Office 98-99 Indoor Stadia 100-103 Urban Ticketing System (URBTIX) 104 Public Libraries 105-115 Museums 116-150 Conservation Office 151-152 Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) 153-154 Major Cultural Events 155-165 6. Administration 166-193 Financial Management 166-167 Human Resources 168-180 Information Technology 181-183 Facilities and Projects 184-185 Outsourcing 186-187 Environmental Efforts 188-190 Public Relations and Publicity 191-192 Public Feedback 193 7. Appendices 194-218 Foreword The LCSD has another fruitful year delivering quality leisure and cultural facilities and events for the people of Hong Kong. In its 2018-19 budget, the Government announced that it would allocate $20 billion to improve cultural facilities in Hong Kong, including the construction of the New Territories East Cultural Centre, the expansion of the Hong Kong Science Museum and the Hong Kong Museum of History, as well as the renovation of Hong Kong City Hall. -

Football Development in Hong Kong ‘We Are Hong Kong’ – Dare to Dream a Final Report December 2009

Football Development in Hong Kong ‘We are Hong Kong’ – Dare to Dream A Final Report December 2009 Part of the Scott Wilson Group Football Development in Hong Kong Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 01 2 Introduction and Context 11 3 International Case Studies 20 4 Structure and Governance of Football in Hong Kong 43 5 Football Facilities 51 6 Football Development – Community to Elite 57 7 Other Key Issues 67 8 Developing and Delivering a Strategic Vision for Football in Hong Kong 71 9 Summary and Way Forward 115 D124955 – FINAL REPORT Version 1 – December 2009 Football Development in Hong Kong Table of Appendices 1 List of Consultees 2 Site Visits Undertaken 2a Sample of Site Visits 3 AFC Assessment of Member Associations 4 Hong Kong Natural Turf Pitches 5 Hong Kong Artificial Turf Pitches 6 Proposed Home Grounds for Hong Kong Professional League 7 Playing Pitch Strategy, Model and Overview 8 Hong Kong Football Association First Division Teams 9 Everton Football Club and South Korea Training Centre Examples 10 FIFA Big Count Statistics 2006 11 National Football Training Centre – Outline Proposals Section 1 Executive Summary www.scottwilson.com www.strategicleisure.co.uk 1 Football Development in Hong Kong 1 Executive Summary Introduction 1.1 Football matters! The link between success in international sport and the ‘mood’ and ‘productivity’ of a nation has long been recognised. Similarly there is sufficient evidence to demonstrate a direct link between participation in sport and the physical and mental health of the individual, the cohesiveness of communities and the prosperity of society as a whole. -

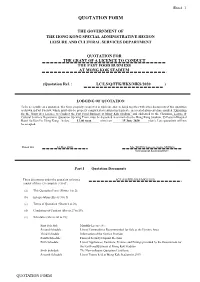

Quotation Form

Sheet 1 QUOTATION FORM THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION LEISURE AND CULTURAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT QUOTATION FOR THE GRANT OF A LICENCE TO CONDUCT THE FAST FOOD BUSNIESS AT MONG KOK STADIUM (Quotation Ref. : LC/LS/Q/FFK/HKS/MKS/2020 ) LODGING OF QUOTATION To be acceptable as a quotation, this form, properly completed in triplicate and enclosed together with other documents of this quotation as shown in Part I below, which must also be properly completed as required in triplicate, in a sealed plain envelope marked “Quotation for the Grant of a Licence to Conduct the Fast Food Business at Mong Kok Stadium” and addressed to the Chairman, Leisure & Cultural Services Department Quotation Opening Team, must be deposited in or mailed to the Hong Kong Stadium, 55 Eastern Hospital Road, So Kon Po, Hong Kong before 12:00 noon (time) on 15 June 2020 (date). Late quotations will not be accepted. Dated this 22 May 2020 Ms. WONG Sau-yin, Lynn, M(HKS) Government Representative Part I — Quotation Documents These documents under the quotation reference LC/LS/Q/FFK/HKS/MKS/2020 consist of three (3) complete sets of : (a) This Quotation Form (Sheets 1 to 2); (b) Interpretation (Sheets 3 to 5); (c) Terms of Quotation (Sheets 6 to 26) (d) Conditions of Contract (Sheets 27 to 59) (e) Schedules (Sheets 60 to 73); First Schedule Monthly Licence Fee Second Schedule List of Commodities Recommended for Sale at the Licence Area Third Schedule Information of the Service Provider Fourth Schedule Form of Security Deposit Election Fifth Schedule -

Match Summary

MATCH SUMMARY TEAMS Sunwolves vs DHL Stormers VENUE Mong Kok Stadium, Hong Kong DATE 19 May 2018 07:15 COMPETITION Vodacom Super Rugby FINAL SCORE 26 - 23 HALFTIME SCORE 10 - 17 TRIES 2 - 3 PLAYER OF THE MATCH SCORING SUMMARY Sunwolves DHL Stormers PLAYER T C P DG PLAYER T C P DG Hayden Parker (J #10) 1 2 3 1 Dillyn Leyds (J #14) 1 0 0 0 Grant Hattingh (J #5) 1 0 0 0 Jean-luc Du Plessis (J #10) 0 1 0 0 J J Engelbrecht (J #13) 2 0 0 0 Sp Marais (J #15) 0 0 2 0 LINE-UP Sunwolves DHL Stormers 1 Shintaro Ishihara (J #1) 1 Jc Janse Van Rensburg (J #1) 2 Shota Horie (J #2) 2 Ramone Samuels (J #2) 3 Takuma Asahara (J #3) 3 Wilco Louw (J #3) 4 Sam Wykes (J #4) 4 Chris Van Zyl (J #4) 5 Grant Hattingh (J #5) 5 Pieter Steph Du Toit (J #5) 6 Michael Leitch (J #6) 6 Cobus Wiese (J #6) 7 Ed Quirk (J #7) 7 Kobus Van Dyk (J #7) 8 Willie Britz (J #8) 8 Nizaam Carr (J #8) 9 Fumiaki Tanaka (J #9) 9 Dewaldt Duvenage (J #9) 10 Hayden Parker (J #10) 10 Jean-luc Du Plessis (J #10) 11 Kenki Fukuoka (J #11) 11 Seabelo Senatla (J #11) 12 Michael Little (J #12) 12 Damian De Allende (J #12) 13 Timothy Lafaele (J #13) 13 J J Engelbrecht (J #13) 14 Akihito Yamada (J #14) 14 Dillyn Leyds (J #14) 15 Kotaro Matsushima (J #15) 15 Sp Marais (J #15) RESERVES Sunwolves DHL Stormers 16 Jaba Bregvadze (J #16) 16 Scarra Ntubeni (J #16) 17 Craig Millar (J #17) 17 Carlu Sadie (J #17) 18 Hencus Van Wyk (J #18) 18 Frans Malherbe (J #18) 19 Uwe Helu (J #19) 19 Jan De Klerk (J #19) 20 Yoshitaka Tokunaga (J #20) 20 Siya Kolisi (J #20) 21 Yutaka Nagare (J #21) 21 Sikhumbuzo Notshe (J